Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

WHALE STRANDING IN NEW ZEALAND

_at_Port_Waikato.jpg)

beached whale at Port Waikato, New Zealand There are a lot whale and marine mammal strandings in New Zealand. Since 1840, more than 5,000 strandings of whales and dolphins have been recorded around the New Zealand coast. Sometimes hundreds of incidents occur annually. Strandings occur all year round but are especially common during the summer months. They usually involve just one or two animals. Mass strandings may involve hundreds of animals.

Vulnerable species include pilot whales, dolphins, and beaked whales. The most common species that strand alone are common dolphins, pygmy sperm whales, and beaked whales. Occasionally mass strandings occur and the majority of these are long-finned pilot whales. Even large whales such as sperm whales have been known to strand occasionally.

Some animals strand due to sickness, injury, or old age, while others are healthy and simply in need of assistance to return to deeper water. Stranding incidents are reported to New Zealand’s Department of Conservation (DOC). Trained volunteers with groups like Project Jonah and conservation staff work support respond to stranding events, providing care, rescue, and in some cases, a ceremonial cultural burial.

Large groups of pilot whales, with several hundred members, have beached themselves on remote New Zealand beaches. So many whales beach themselves in New Zealand that scientists there have developed special pontoons that allow the whales be floated in less than a foot of water.

Police and commuters were furious when they found a group a killer whales they thought were stranded near Wellington's inter-island ferry were really rubber dorsal fins attached to wooden blocks left as part of an April Fools joke.

Related Articles:

WHALE STRANDINGS IN AUSTRALIA: INCIDENTS, REASONS WHY, RESCUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

PILOT WHALES — LONG-FINNED, SHORT-FINNED — CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

BEACHED AND STRANDED WHALES: WHY, SOLAR STORMS, HUMANS, U.S. NAVY SONAR

ioa.factsanddetails.com

WHALES (ORCAS, SPERM AND BEAKED WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com; Articles:

TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com;

WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE COMMUNICATION AND SENSES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ENDANGERED WHALES AND HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Why There Are So Many Beached Whales in New Zealand

New Zealand's complex geography with long coastlines and shallow beaches is thought to play a significant role in whale standings by potentially confusing whales that use echolocation, which can get confused by gently sloping sandy beaches. Other factors like disease, injury, or following prey are also involved. Changes in sea temperature and prey distribution due to global warming may also contribute to strandings, as animals follow their food sources into shallower waters.

Most beached whale events involve toothed whales not baleen whales. Theories behind why they occur include high winds that throw off currents and storms that cloud up the water. Whales are often beached in gently sloping beaches or places with narrow continental shelves. Many of the beached whale events occur with highly social animals. It is possible their leader gets lost or that healthy ones follow sick ones or are escaping predators. Other theorize the beachings could be related to geomagnetic interference from elements such as iron or problems with the whale’s sonar and echolocation systems. Australian marine scientist Catherine Kemper told AFP the theories are almost endless but many may be caused by disruptions in the echolocation sonar of toothed whale making it difficult for them to find their way.

Some say they occur as a result of disturbances in the Earth’s magnetic fields; other say they are due to shifts in feeding grounds or being led astray by man-made sounds. One theory, first put forth in a Maori legend and repetaed in the film “The Whale Rider,” suggested that a sick leader or a young whale washes a shore and the other follow suit in an effort to rescue the first stranded whale.

Australian scientists have found that mass beachings of whales and dolphins in the southern hemisphere come in 12-year cycles that coincide with cooler, nutrient-rich ocean currents moving from the south and swelling fish stocks, bring the marines mammals close to shore, where they can get trapped by tides and sand bars, as they pursue food close to shore. Some theorize that this phenomena could increase with global warming as this pattern increases and bring more whales and dolphins close to shore.

Some scientists say the main reason that so many whales get stranded in Australia and New Zealand is not because there is something unusual about them but simply because Australia and New Zealand are located in an area of ocean where there are many whales and dolphins. Tasmanian wildlife officer Shane Hunniford said “If you look at spaceship Earth, Tasmania and New Zealand both stick out into the Southern Ocean and that’s a playground for whales and dolphins.”

Rescuing Beached Whales in New Zealand

rescue effort at Farewell Spit, South Island, New Zealand New Zealand’s Department of Conservation (DOC) manages whale strandings and rescues, with the help of local communities, volunteers, and organisations like Project Jonah. DOC responds to an average of 85 stranding incidents per year, usually of single animals. Healthy animals are often refloated at high tide, with the help of the public, to encourage them back to sea. Deceased animals are given a proper burial or handled for scientific study, sometimes involving cultural ceremonies by Māori groups, who consider whales sacred. [Source: New Zealand Department of Conservation]

Since 1985 a New Zealand group called Project Jonah has used inflatable pontoons to rescue thousands of marine animals ranging in size from dolphins to 45-foot Bryde's whales. Beached whales usually die from fatally overheating. To prevent this from happening the animals are rolled over so a mat can be placed underneath. As the tide rises pontoons are attached to the mat and inflated. "The pontoons allow us to float a huge animal in less than a foot of water," one biologist told National Geographic.

The DOC is legally responsible for implementing the Marine Mammals Protection Act 1978. This means they is in charge at marine mammal stranding events. The DOC responsibilities include: 1) protecting the welfare of stranded animals; 2) disposing of any dead marine mammals; 3) ensuring the health and safety of staff, volunteers, and the public; 4) enabling cultural protocols, which involves consulting with local iwi and hapū through every step of the stranding, including rescue, euthanasia, sampling and disposal; 5) enabling research, such as through the collection of scientific samples.

Anyone can help out at a stranding event as long as they are physically able. To be prepared to help at a stranding people can attend a Marine Mammal Medic Course run by Project Jonah. Medics who have completed the course are authorized to help rescue stranded whales and dolphins. Local volunteers are called on to help care for the mammals until dark; in some cases anyone joining the rescue effort must have a wetsuit. During one stranding event one official said: "We want people with wetsuits, buckets and sheets. They're really calling for the locals who can get there tonight and be of use before it gets dark."

In December 2005, Volunteers and conservation staff worked to save more than 120 pilot whales stranded on stranded on Puponga Beach near Farewell Spit. John Mason, the local manager of the Department of Conservation, says the whales became standed as they tide went out and the whales were kept damp with buckets of water and wet sheets. He says it will be too dangerous for the staff and volunteers to remain on the beach overnight. "It's really too dangerous to have people in the sea with the whales," Mr Mason said. It is hoped some of the whales will refloat themselves at high tide early tomorrow morning. [Source: AFP, December 20, 2005]

Not all rescue operations have a happy ending. In October 2009, wildlife workers in New Zealand shot 41 whales that beached on the South Island after the rescue operation had become too dangerous. Forty-nine pilot whales had come ashore at Farewell Spit. Eight of them died on the beaches. The remaining 41 whales were spread over a wide area, more than a kilometer from the shore. A New Zealand conservation official said it was hopeless to try refloating the whales because of rough seas. He said wildlife officers shot the whales to prevent them from suffering a long and painful death. It was the second major stranding of whales in the area in recent weeks. Volunteers managed to refloat more than 100 whales that beached in the earlier incident. [Source: Voice of America, October 31, 2009]

Whale Strandings in New Zealand, 1978–2009

In the newspapers there are periodically stories of whale beachings involving dozens of individuals. In December 2009, 125 pilot whales died when they beached themselves on two beaches in New Zealand. Sixty-three whales died on a beach on the North Island of New Zealand and 43 were rescued by volunteers who were able to keep them wet until they could be picked and carried back to sea by the high tide. Scientists speculated that perhaps their leader was sick or they got lost in a shallow harbor and could not use their sonar to find a way out. Hundreds of kilometers away on a beach on the South island, 105 long-finned pilot whales died in a remote isolated area. Rescuers could not reach them in time.

In November 2004, 53 pilot whales died at a beach at Opoutere, 60 miles east of Auckland on the North Island. Officials said 73 whales had become stranded there, but 20 were saved. Of those 20, more were expected to die because many were too weak to follow the others out to sea. “Some of them had suffered pretty significantly on the beach,” New Zealand conservation department manager John Gaukrodger told reporters. Around the same time a 30-foot sperm whale washed up on a beach west of Auckland. Officials said they were not sure if the whale had died at sea and washed up or had stranded itself. They said it was not linked to the Opoutere beaching. [Source: Reuters, November 28, 2004]

Sheryl Gibney, a rescue coordinator with New Zealand’s Project Jonah, said high offshore winds and plentiful supplies of mackerel close to the coast could be possible explanations. “Normally with pilot whales, because they’re so closely socially bonded, if one gets into trouble the others are not going to leave,” Gibney said. “Some will come in and try and assist it, they get stranded, then more will come.”

Almost 9,000 whales and dolphins were stranded in New Zealand between 1978 and 2004. Only about a quarter of them were saved. Species included Grey’s beaked whale, the Pygmy sperm whale, the sperm whale, the long-finned pilot whale, and the false killer whale (which is actually a dolphin). There were 167 incidents involving Grey’s beaked whales of which 279 were stranded and 15 were rescued. There were 201 incidents involving pygmy sperm whales of which 242 were stranded and 21 were rescued. There were 142 incidents involving sperm whales of which 189 were stranded and one was rescued. [Source: New Zealand government]

There were 179 incidents involving long-finned pilot whales of which 5,999 were stranded and 1,868 were rescued. By contrast here were only nine incidents involving short-finned pilot whales of which 52 were stranded and six were rescued. Pilot whales are technically not whales; they are among of the largest members of the dolphin family, There were 788 incidents involving other species of dolphins of which 1,741 were stranded and 302 were rescued.

Farewell Spit, New Zealand — Whale Stranding Hot Spot

Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic: The short-finned pilot whale is a large species of dolphin with a dark-grey body and a bulbous head. It’s an intensely social animal that spends its life in the company of others. And that, sadly, is also how it sometimes dies. New Zealand’s Farewell Spit is a notorious whale trap where pilot whales regularly strand; up to 650 long-finned pilot whales beached there in February 2017, of which 400 or so were saved. [Source: Ed Yong, The Atlantic, March 24, 2018]

Stranding hot spots like Farewell Spit often include hook-shaped pieces of land jutting out into the water. The gently sloping sandy beaches at these sites may not reflect the whales’ sonar back at them, prompting them to think that they’re actually in deeper water. These regions are also complicated estuarine environments where rapidly receding tides can easily strand inexperienced deepwater species. Perhaps this is why shallow-water cetaceans, which have most experience with such conditions, rarely strand. Perhaps this also explains why pilot whales will often re--strand themselves once they’re rescued. Whales might enter these traps because they’re pursuing prey into unfamiliar waters. . Or they might be fleeing from predators like orcas, or be sent astray by extreme weather. They might be weakened by injuries, viral infections, or mere old age, and seek shallower waters where they can more easily breathe.

In February 2017, more than 400 whales beached themselves in a mass stranding at the sandspit at the northern end of Golden Bay. About 300 died but the surviving 100 were successfully refloated at high tide about lunchtime today. The New Zealand Herald reported: Two groups of previously stranded whales at Farewell Spit in Golden Bay are beached again and the Department of Conservation is urgently calling for more volunteers. Up to 120 of the 300 pilot whales heading out to sea at high tide earlier today did not make it the 26 kilometers along the sandspit to safety. [Source: New Zealand Herald, February 11, 2017]

DoC Nelson ranger Kath Inwood said two groups of whales, 70 in one and 50 in the other, were beached about three kilometers from the original stranding site on Thursday night involving 416 whales. Of those, 300 died and the rest were successfully refloated today and joined another pod of 200. DoC senior communications advisor Herb Christophers said they would not be attempting to refloat the whales at the midnight high tide due to health and safety risks. He said they had to be careful no volunteers got hurt. "Black fish, dark night, a flick of the tail and somebody could go down and nobody would know." Instead they would be back first thing in the morning to check the status of the whales and attempt to refloat any survivors at midday, Christophers said.

Weather Blamed for Whale Beachings in New Zealand

Research by the University of Tasmania's department of marine biology has shown that mass strandings of whales and dolphins are cyclical events caused by westerly winds increasing in strength every 12 years over the Southern Ocean. Marine biologist Dr Karen Evans said the study, presented to the Australian Marine Sciences Association annual conference in July 2004, has shown strandings have a 12-year cycle, and the peak is being reached in November 2004 when 150 whales and dolphins become stranded on Australian and New Zealand beaches. [Source: Agençe France-Presse, December 1, 2004

AFP reported: The research shows cyclical westerly and southerly winds pushed sub-Antarctic waters north, drawing colder, nutrient-rich waters needed by whales and dolphins closer to the surface. "You get an increase in the number of whales [around Tasmania and Victoria] and therefore a higher likelihood of animals to strand," she said.

In New Zealand rescuers succeeded in returning to the sea 20 of the 21 pilot whales found alive on a beach near Whangamata on the North Island's east coast, and put down the last one. Up to 70 volunteers including conservation department staff kept the last of the live whales afloat until they were strong enough to swim away. But more than 50 of the pod of 73 whales, which lay undiscovered on isolated Opoutere beach until Monday, had died. Conservation department area manager John Gaukrodger said there were no signs the refloated whales were returning to the beach.

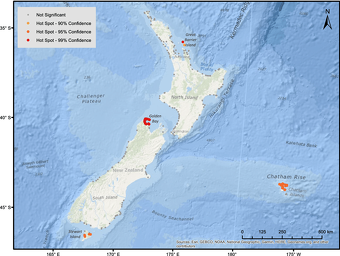

477 Whales Die in New Zealand Strandings

In October 2022, some 477 pilot whales died after stranding themselves on two remote New Zealand beaches in a period of a couple of days. None of the stranded whales could be refloated and all either died naturally or were euthanized in a “heartbreaking” loss, said Daren Grover, the general manager of Project Jonah. The whales beached themselves on the Chatham Islands, which are home to about 600 people and located about 800 kilometers (500 miles) east of New Zealand's main islands. The DOC said 232 whales stranded themselves at Tupuangi Beach and another 245 at Waihere Bay. [Source: Nick Perry, Associated Press, October 12, 2022]

“These events are tough, challenging situations,” the Department of Conservation wrote in a Facebook post. “Although they are natural occurrences, they are still sad and difficult for those helping.” Grover said the remote location and presence of sharks in the surrounding waters meant they couldn't mobilize volunteers to try to refloat the whales as they have in past stranding events.

“We do not actively refloat whales on the Chatham Islands due to the risk of shark attack to humans and the whales themselves, so euthanasia was the kindest option,” said Dave Lundquist, a technical marine advisor for the conservation department.

Grover said there is a lot of food for the whales around the Chatham Islands, and as they swim closer to land, they would quickly find themselves going from very deep to shallow water. “They rely on their echolocation and yet it doesn't tell them that they are running out of water,” Grover said. “They come closer and closer to shore and become disoriented. The tide can then drop from below them and before they know it, they're stranded on the beach.”

Because of the remote location of the beaches, the whale carcasses won't be buried or towed out to sea, as is often the case, but instead will be left to decompose, Grover said. “Nature is a great recycler and all the energy stored within the bodies of all the whales will be returned to nature quite quickly,” he said.

New Zealand Rescuers Use Trucks to Save 14 Whales from Stranded Pod

In September 2010 AP reported: “Rescuers who battled exhaustion and darkness succeeded in saving 14 pilot whales from a pod of 74 that stranded on a remote New Zealand beach. A total of 24 whales were trucked 30 miles (50 kilometers) from Spirits Bay, where they beached on to be refloated in more sheltered waters of Rarawa Beach, an hour's drive south. Two died en route, another on the beach and seven had to be euthanized after re-stranding. [Source: Associated Press, September 24, 2010]

Rescuers in boats and on shore worked strenuously to prevent those seven whales from beaching themselves again but were unsuccessful, Department of Conservation incident controller Jonathan Maxwell said. "By that stage it was dark, and all of us were pretty exhausted. We all agreed we had done everything we could for these animals. The most humane course of action was to end their suffering," Maxwell told the New Zealand Herald.

The whales were transported between beaches in six trucks packed with straw and sand, in the largest operation of its kind in New Zealand. Department of Conservation staff and volunteers used three boats and two jet skis to herd the whales out to sea, Doc community relations manager Carolyn Smith said. Twenty-one were eventually guided into the open sea but seven turned back to land.

"As far as I'm aware, this has not been tried before to this scale (in New Zealand)," Anton van Helen, a whale expert at New Zealand's national museum, told the Herald. "Its a huge undertaking and definitely contains risks for the whales, but is basically their only chance."

New Zealand has one of the world's highest rates of whale strandings, mainly during their migrations to and from Antarctic waters, one of which begins in September. Since 1840, the Department of Conservation has recorded more than 5,000 strandings of whales and dolphins around the New Zealand coast. Scientists have not been able to determine why whales become stranded.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025