Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

KIWI SPECIES

five kiwi species Amanda Riley Art

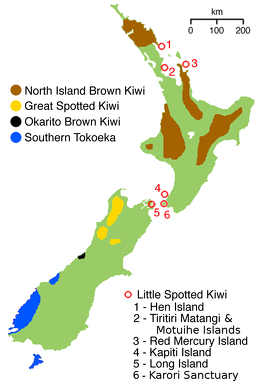

There are five recognised species of kiwis, are all native to New Zealand: 1) the North Island brown kiwi, 2) the great spotted kiwi (roroa), 3) the little spotted kiwi, 4) Okarito brown kiwi (Rowi), and 5) the Southern brown kiwi (Tokoeka) kiwi. For a long time it was thought there were three species of kiwi, then it was thought there were four. The five species have been distinguished through genetic research, which confirmed that the brown kiwi should be separated into three distinct species. Stewart Island is home to New Zealand's last major population of wild kiwi, with 15,000 to 20,000 southern brown kiwis.

1) North Island Brown Kiwis (Apteryx mantelli) are found in the North Island of New Zealand.

2) Southern Brown Kiwis (Apteryx australis) were previously referred to as Tokoeka.

3) Okarito Brown Kiwis (Apteryx rowi) is rare species, formerly called Rowis. The only wild population lives in the Ōkārito forest on the West Coast of the South Island.

4) Great Spotted Kiwis (Apteryx haastii) are also known as roroa. They are the largest kiwi species and are found in the South Island.

5) Little Spotted Kiwis (Apteryx owenii) are the smallest of the kiwi species. They are now primarily found on predator-free offshore islands and within sanctuaries like Zealandia.

North Island brown kiwis, southern brown kiwis and Okarito brown kiwis were formerly considered subspecies of brown kiwis (Apteryx australis): 1) North Island brown kiwis ( now Apteryx mantelli) were known as Apteryx australis mantelli. 2) Southern brown kiwi (now Apteryx australis) were known as Apteryx australis australis (for those on the South Island, now Fiordland kiwis) and Apteryx australis lawryi (for those on Stewart Island, now Stewart Island kiwis). 3) Okarito Brown Kiwis (Apteryx rowi) are rare species, formerly called Rowis. The only wild population lives in the Ōkārito forest on the West Coast of the South Island. Their population has only about 600 birds.

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: Recent research into the genetic variation between populations of brown kiwi shows that there are distinct but almost identical species, not the traditional North, South and Stewart Island races. Instead, the distribution pattern may fit better with the New Zealand geography of the ice ages of the past one or two million years, when lower sea levels saw the North and South Islands much closer together, if not actually linked, and kiwi habitat in the western South Island was broken in the middle by ice and tundra. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

RELATED ARTICLES:

KIWIS: EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS, HUMANS AND CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

KEAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PLAYFULNESS, INTELLIGENCE, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KAKAPO: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SAVING THEM FROM EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOKAKOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

North Island Brown Kiwis

North Island brown kiwis (Apteryx mantelli) are the most common kiwi species. They are widespread in the northern two-thirds of the North Island of New Zealand, particularly in Northland and Taranak. There are about 35,000 remaining. The eggs of North Island brown kiwis are among the largest eggs relative to body size of any bird. North Island brown kiwis are the only species of kiwi found internationally in zoos. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present in North Island brown kiwis.: Females are larger than males. Females stand about 40 centimeters (16 inches) tall and and weigh about 2.6 kilograms (5.7 pounds). Males weigh about two kilograms (4.4 pounds). Their plumage is streaky red-brown and spiky. The genome of Apteryx mantelli was sequenced in 2015. [Source: Wikipedia]

North Island brown kiwi seem to prefer densely vegetated lowland and coastal forests. Their population densities are highest in such places but they have also shown they can adapt to a range of habitat types. The most common form of foraging by North Island brown is tapping and probing the ground with their beaks in which they seek out prey with smell and feel.

The most common and distinctive sound produced by North Island brown kiwis is the “whistle call”, which is performed solo or in a duet. Vocalisations by these birds are believed to play roles in territory defence, social communication and courtship. Call rates tend to increase during the breeding period and decrease during the incubation period. Mates perform duets as a form of pair communication. The vocalisations of males and females are different. Male North Island brown kiwi calls produce high-pitched, multi-harmonic notes, whereas females typically emit low-frequency notes. These differences are attributed to differences in the structure and size of their sound producing throat organs. Additionally, males have been observed to have a significantly higher call rate compared to females.

North Island Kiwi Reproduction and Chicks

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: Almost indistinguishable against dry fern fronds and bark, a North Island brown kiwi crouches outside the entrance to one of its burrows. Within each territory will be dozens of burrows used by a pair of birds, each as well camouflaged as its proprietors.[Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

In most varieties of kiwi, the typical clutch is one egg, laid two to three weeks after mating. Only North Island brown kiwi regularly lay a second egg, two to fourder, though: its tummy, taut like a balloon, is distended with yolk, which will nourish it for the first week of its life. Kiwi eggs are 65 per cent yolk, compared with the 35 to 40 per cent typical of most birds.

Within a few days, the chick, which is born fully feathered, begins to venture outside the burrow, and by day 10 it is out for most of the night. Its beak is as long and as pink as a child’s finger, its feathers soft and moist and smelling of a rotting log. Somehow, it knows all about the business of being a kiwi, of finding the right food and shelter. Somehow, it knows that its best chance of survival is eating lots and growing fast. What it probably doesn’t know is that almost inevitably it will fail.

In the wild, only five chicks in a hundred survive until their first birthday. The chief cause of mortality is the stoat, a fierce predator which has no trouble despatching young kiwi that weigh even four or five times its own weight. Only when birds have attained a weight of 1200 g-which takes at least six hazardous months-do stoats leave them alone.

Southern Brown Kiwis

Southern brown kiwis (Apteryx australis) are also known as tokoeka, common kiwis and brown kiwis. They are a species of kiwi from South Island of New Zealand. Until 2000 they and North Island brown kiwis were considered subspecies of the same species and still are by some authorities.

The second largest of the kiwi species, southern brown kiwis are about 40 centimeters (1.3 feet) tall and weigh around three kilograms (6.6 pounds). Groups of southern brown kiwis regularly forage for sandhoppers and other arthropods on beaches on Stewart island, probing with their beaks into the sand for prey. Afterwards the birds can sometimes be seen drinking from streams that empty into the sea. Stewart Island is home to New Zealand last major population of wild kiwis, with 15,000 to 20,000 southern brown kiwis there. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Southern brown kiwis live in temperate forests and grasslands. They prefer to live in large, dark forest areas, which allow camouflage for the birds as they sleep during the day. In undisturbed habitats, they dig burrows under stones, banks of streams, or in soft flat open ground. In disturbed areas, they have adapted to human presence by making burrows in rough farmland under logs and shrubs. Their habitat ranges from sea level to areas at elevations of 1,200 meters (3,937 feet).[Source: Smitha Gudipati, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Southern brown kiwis are listed as Vulnerable. While their numbers are decreasing, the population is still relatively stable, with estimates of around 21,350 birds. The primary threat to these birds is predation by introduced mammals such as dogs, pigs, cats, possums and stoats.

See Separate Article: SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Great Spotted Kiwis

Great spotted kiwis (Apteryx haastii) are also known as roroa. They are the largest species of kiwi, standing about 45 centimeters (1½ feet) tall and weighing up to 3.3 kilograms (7.3 pounds). They have grey-brown plumage with lighter bands and both females and males incubate the eggs. Great spotted kiwis live mainly in the beech forests, hardwood forests, other forested areas, scrublands and grasslands of northeastern South Island. They rustle around in leaf litter at night, forage under logs, looking for earthworms. They have large nostrils at the end of their bill which they use tap and probe the forest floor. Their population is estimated at over 20,000, distributed through the more mountainous parts of northwest Nelson, the northern West Coast, and the Southern Alps of the South Island.

Great spotted kiwis are found primarily in three regions of New Zealand: 1) northwest Nelson, home of the largest population 2) the Paparoa Range, where the second largest population lives; and 3) the Arthur’s Pass-Hurunui district of the Southern Alps. In 2004 a population was established at Nelson Lake. They are found from sea level to 1,500 meters (4,921 feet) in forested habitats and from 700 to 1,100 meters (2297 to 3,609 feet) in subalpine habitats. The places they live can be very wet, with rainfall ranging from 120 to 400 centimeters (four to 13 feet) a year. [Source: Cari Mcgregor, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, great spotted kiwis are listed as Vulnerable. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. In 1996, the population size was around 22,000 individuals and declined to 12,000 by 2006.At that time the largest population of 11,000 was in northeast Nelson in the north and 3,000 in the south. There were about 6,300 in the Paparoa Ranges and about 3,000 at Arthur's Pass. There are areas in the north where great spotted kiwis are stable. However, in most areas, the population of great spotted kiwis declines at about two percent a year. Great spotted kiwis populations have declined about 90 percent in the last 100 years mainly due to introduced mammalian predators such as dogs, cats, stoats, domestic ferrets and common brushtail possums. A predator control project — The Rotoiti Nature Recovery Project — designed to protect great spotted kiwis from introduced predators has been set up.

Great Spotted Kiwi Characteristics, Diet and Longevity

Great spotted kiwis are stout, long-billed birds. They range in weight from 2.4 to 3.3 kilograms (5.3 to 7.3 pounds) and are 44 to 55 centimeters (1.4 to 1.8 feet) tall. The bill length of great spotted kiwis ranges from 8.3 to 13.5 centimeters (3.3 to 5.6 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Females are larger than males, with females weighing about 3.3 kilograms (7.3 lpounds) and males about 2.4 kilograms (5.3 pounds). The bills of males are 8.3 to 10.4 centimeters in length, while those of females are 13.3 to 13.5 centimeters long. [Source: Cari Mcgregor, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Great spotted kiwis appear spotted because the arrangement of their grey, brown, and off-white feathers. The legs are short and muscular and they have large four-toed feet; three toes facing forward and one in the back. Because they do not fly, their feathers are soft, much like the hair of mammals. As they are nocturnal, their eyes are small and underdeveloped and their olfactory organs are larger than those of diurnal birds that are are active in the daytime. The bills of great spotted kiwis are white grey and take up to five years to develop to their adult size. Th nostrils are located closer to the tip of the bill.

Great spotted kiwis are omnivores (animals that eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). Animal foods include insects, terrestrial worms and aquatic crustaceans. Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, seeds, grains, nuts and fruit. Great spotted kiwis prefer seasonal fruits, but these do always make up the bulk of their diet. A study in the 1980s, found that the diet of great spotted kiwis consists of 40 to 45 percent earthworms, 40 to 45 percent other invertebrates, such as lepidopterans (mainly moths), beetles, spiders and hemipterans (mainly cicadas), and 10 to 15 percent seeds and fruits. Great spotted kiwis have a probing curved bill that helps them forage for food. This bill also helps reduce the dust inhaled while searching for food.

The lifespan of great spotted kiwis in captivity is 12 to 33 years. It is estimated that of they survive the first year their average lifespan in the wild is 20 years. A study in the 1990s, determined the average yearly rate of mortality for great spotted kiwis was around 10.7 percent, with introduced predators being the main limiting factor in their lifespan. A study in the 2000s, said that predators were responsible for the death of 60 percent of young kiwis. In captivity, great spotted kiwis have a higher chance of surviving hatching. In the wild, 29 percent of eggs reach the full term incubation, while the percentage of this in captivity is 79 percent. The study in the 2000s found that, in captivity, great spotted kiwis could be afflicted with a variety of diseases and health issues, in some cases stemming from ingesting foreign particles and the transfer of bacterial and fungal infections from other birds. Bacterial diseases include septicemia, pneumonia, bronchitis, and avian tuberculosis. Fungal diseases include cryptococcosis and aspergillosis.

Great Spotted Kiwi Behavior and Communication

Great spotted kiwis are cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). Their home territories range for 19.6 and 35.4 hectares (48.3 to 87.5 acres), with an average of 29.3 hectares (72.4 acres). The distance per hour that the kiwi travels at night ranges from seven to 433 meters. Territories in the Northwest Nelson region have been reported to range from 0.08 to 0.26 square kilometers. Some birds have charged human intruders in their forest habitats. [Source: Cari Mcgregor, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Great spotted kiwis are usually solitary, but form pairs during the mating and incubation seasons. They sometimes form temporary groups around fruiting trees. Great spotted kiwis do not fly; instead they have very muscular legs. They remain mostly on the ground as their food sources are there. Great spotted kiwis sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They employ choruses (joint displays, usually with sounds, by individuals of the same or different species) and pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species). The great spotted kiwi sense of smell is so good they can locate food without vision.

Great spotted kiwis are very vocal. It is common to only hear kiwis and not actually see them. The sexes have different vocalizations. According to Animal Diversity Web: Males make a loud, drawn out whistle that is repeated 10 to 20 times and can be heard up to 1.5 kilometers. Females make an unpleasant hoarse, guttural sound that is repeated around 10 to 20 times. Their call is used for a contact call and a defense call, and young kiwis make calls when they are alarmed. Great spotted kiwis are more vocal in the winter and the spring, two to three hours after sunset, which is when they lay eggs.

Great Spotted Kiwi Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Great spotted kiwis are monogamous (having one mate at a time) and are K-strategist breeders, meaning they invest most of their energy into just a few offspring. One study found that paired male and female great spotted kiwis spend 20 percent of their time together, largely because when they feed they do so apart. Great spotted kiwis engage in seasonal breeding — generally breed once yearly between July and December. The number of eggs laid each season is usually one. But if the first egg fails to yield a chick the female may lay a second egg but this is uncommon as it requires so much energy to produce a single, large egg. The average time to hatching is 70 days. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age 3.75 years and males do so at 2.25 years. In captivity, great spotted kiwi females achieve maximum success in raising young when they are five to 26 years old; Males achieve maximum success in raising young from seven to 28 years old. [Source: Cari Mcgregor, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Great spotted kiwis use a variety of visual and auditory cues in mating. Males engage in “bill-to-bill grunting and chasing, leaping, and snorting” to attract a potential mates. Great spotted kiwis are very territorial in the breeding and nesting season and may use pheromones to mark their territories. Parental care is provided by both females and males, with most of the incubation done by males. When males are incubating the eggs, they lose feathers on their lower stomach and develops a bald patch in order to enhance heat transfer to the egg. Males and females rotate incubation times throughout the day and night, with males typically incubating during the day and night, and females incubate the egg for about five hours at night while males forage for food.

The nest of great spotted kiwis is comprised of vegetation and built in burrows, although occasionally nests are exposed. Great spotted kiwis are hard to observe when they are incubating, because males are very territorial. Oftentimes they will abandon the nest if it is disturbed. Agitated males are known to crack open the egg if humans approach, but only during early stages of incubation. In order to reduce heat loss, great spotted kiwis use the warmth of their feet to incubate the egg. The yolk sac is rich in energy. The egg has the same amount of energy as an emu yolk, from 229 to 251 grams of energy. The average fledging age for great spotted kiwis is two to four weeks and the average time to independence is four to 12 months.

Little Spotted Kiwis

Little spotted kiwis (Apteryx owenii) are the smallest kiwi species. Also known as little grey kiwis and kiwi pukupuku, they are about the size of a small chickens, standing 25 centimeters (9.8 inches) tall, with the female weighing 1.3 kilograms (2.9 pounds). Little spotted kiwis are found on Kapiti Island and perhaps can still be found in remote areas of the South Island of New Zealand. They are strictly terrestrial and usually occur in temperate, evergreen, broadleaf forests and shrublands. [Source: Robert Naumann, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|; Wikipedia]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Little spotted kiwis are listed as Near Threatened. They are one of the most threatened kiwi species. They are small and docile and unable to withstand predation by introduced stoats, pigs and cats, leading to their apparent extinction on the mainland. Habitat loss and degradation by humans has also contributed to the decline this species. There are about 1350 little spotted kiwis on Kapiti Island. They have been introduced to other predator-free islands, where they appear to be establishing themselves with about 50 on each island. Captive breeding has been attempted since 1970s, but hasn’t been very successful. It was not until 1989 that the first chick was successfully reared. |=|

Little spotted kiwis mate in the early spring, mostly within the first few weeks of September. They nest in burrows on the forest floor, laying one, rarely two eggs. Eggs are incubated by males. During the 70-day incubation period amles are with the eggs about 21 hours a day. Females help take care of young after they hatch. Both parents supervise the chick at night for protection. Adult kiwis do not feed their young. After hatching, the chicks feed from the yolk sac in the egg for the first few days. Afterwards they probe the forest for food like adults, independent of their parents except when they provide protection.

Little spotted kiwi are nocturnal (active at night). They remain in their burrows during the day and are dispersed in strongly territorial pairs, relying on calls to maintain their territory. Pairs may maintain the same territory for years. Kiwis in generally are omnivores. Little spotted kiwi finds food on the forest floor and in the soil by probing to the full depth of their bill. Earthworms, cockchafer beetle larvae, catepillars, cranefly larvae, and spiders are the most common foods. Fruit off the hinau tree is also commonly consumed. Worms make up the largest percentage of their diet.

Okarito Kiwis

Okarito kiwis (Apteryx rowi) were first identified as a new species in 1994. They are slightly smaller than North Island brown kiwsi and have a greyish tinge to their plumage and sometimes white facial feathers. Females lay up to three eggs in a season, each one in a different nest and each weighing about a fifth a the female’s weight. Males and females both incubate the eggs. Their distribution is now limited to a small area on the West Coast of the South Island, but studies of ancient DNA have shown that before the arrival if humans in New Zealand they were far more widespread on the western side of the South Island and were the main kiwi species on the southern half of the North Island.

On his effort to find to track down an Okarito kiwi, Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: I drive up to the glaciers, to the block of land between the Waiho and Okarito Rivers. I want to walk in the coastal forest at night and listen out for the rarest of our kiwi, the Okarito brown. There isn’t much hope of hearing them, I know, because the night is bright, near the full moon, and that usually puts a damper on kiwi vocalisation. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Suddenly, there is a rustle in the ferns, then a dog-like snuffling, and out of the forest, across a small ditch and on to the trail hops a familiar hunchbacked figure.” It moves “with the stop-go approach of a puppy, tentative yet uncontrollably curious. It moves towards me with a series of jolty, patting footfalls, freezing, craning its neck, sniffing the air, taking a few more steps.

Now it is standing at my feet, the rarest kiwi in the world, touching me with its beak, examining me as a doctor would with a stethoscope. I melt into this magical moment of communion with the ghost of the forest, and feel my throat knotting up as I remember what McLennan said about the soul of the land and how it touched his own. Suddenly, the little rascal jumps up and kicks me! It is a kangaroo kind of kick, with a catlike scratch, as feeble and experimental as the bird is young, but the attitude is there already, and the message is clear: “This is my turf. Hop it!”

I take heed. The bird, I learn later, is one of the new generation of kiwi, hatched and brought up in captivity and released back into the wild. It has obviously made the transition successfully. It found, claimed and defended its territory — no mean feat in this tough neighbourhood. It was curious and brave, streetwise and assertive; it stood its ground.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025