Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

KIWIS

Kiwis are flightless birds that are generally about the size of a chicken. Residing primarily in evergreen forests, swamps and areas with dense undergrowth in northern North Island and on Stewart Island south of the South Island, they are the unofficial national symbol of New Zealand and the nickname for New Zealanders. They have also traditionally been esteemed by Maori chiefs who sometimes wore cloaks adorned with kiwi feathers. [Source: Michael Taborsky and Barbara Taborsky, Natural History magazine, December 1993]

There are five recognised species of kiwis, are all native to New Zealand: 1) the North Island brown kiwi, 2) the great spotted kiwi (roroa), 3) the little spotted kiwi, 4) the Rowi, and 5) the Southern brown kiwi (Tokoeka) kiwi. For a long time it was thought there were three species of kiwi, then it was thought there were four. The five species have been distinguished through genetic research, which confirmed that the brown kiwi should be separated into three distinct species.

All kiwis are flightless, nocturnal ground dwellers. They were once thought to be a species of moa. DNA sequence comparisons have yielded the conclusion that kiwi are much more closely related to the extinct elephant birds of Madagascar than to moas with which they shared New Zealand. Although they are currently only found in New Zealand, fossil evidence has shown that ancestors of kiwis occurred in the North Hemisphere in the Paleocene Period (66 million to 56 million years ago) and Eocene Period (56 million to 33.9 million years ago). The ancient ancestors of kiwi were probably flying birds that evolved into ground dwellers because they had no natural predators.

Books: “The Incredible Kiwi” by Neville Peat (Random Century, 1990); “Kiwi: New Zealand’s Remarkable Bird” by Neville Peat (Godwit, 1999); “Kiwis” edited by Errol Fuller (SeTo, 1990) with excellent kiwi paintings of Ray Harris-Ching, a renowned bird painter

RELATED ARTICLES:

KIWI SPECIES: NORTHERN, SOUTHERN, SPOTTED, LARGEST, SMALLEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS, HUMANS AND CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

KEAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PLAYFULNESS, INTELLIGENCE, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KAKAPO: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SAVING THEM FROM EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOKAKOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Ratites

Kiwis are the smallest ratites, a group that embraces all flightless birds that lack a keel (a ridge of bone that extends outward from the breastbone on which flight muscles of flying birds are attached). Ratites are comprised of six extant families and some extinct families. The five families are Aptergyidae (kiwis), Casuariidae (cassowaries), Dromaiidae (emus), Rheidae (rheas), Tinamidae (Tinamous) and Struthionidae (ostriches). The family for the elephant bird is the extinct ratite family Aepyornithidae. The "moa family" belong the extinct Dinornithiformes. Ratites They are mostly large, long-necked, and long-legged, with the exceptions being the kiwi, which is also the only nocturnal extant ratite, and tinamous which can fly. Ratites were previously known as Struthioniformes. The name ratite is derived the birds’ raft raft-like sternum. [Source: Wikipedia, Ellie Bollich, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: The name ratite, from ratis, Latin for raft, refers to the birds’ sternum, which is flat and raft-like, lacking a keel to which flight muscles could be attached. The sterna of flighted birds have a keel to which their large flight muscles are attached, and these birds are sometimes termed carinates (from the Latin carina, a keel). Just to confuse the issue, though, some ratites — the South American tinamous, for example — have a keeled breast-bone and can fly. On the other hand, the kakapo, whose parrot relatives can fly extremely well, have a sternum as flat as that of any kiwi or moa. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

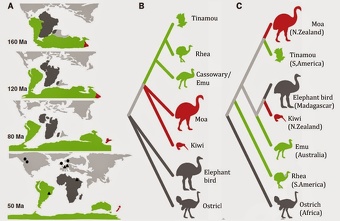

It was first thought that ratites shared a common flightless ancestor on the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which later fragmented, leading to the diversification of ratites on different continents. However, modern genetic studies suggest that ratites may have lost the ability to fly independently and the ancestors of living ratites diverged relatively recently, after the breakup of Gondwana. This suggests that the loss of flight occurred in different ratite lineages — an example of convergent evolution, the process by which distantly related animals independently evolve similar traits or features as a result of adapting to similar environments or ecological niches.

Evidence suggests that ratites might have evolved flightlessness multiple times, with different lineages developing similar traits (such as large size, reduced wings) in response to similar environmental pressures. For example, kiwis, despite being geographically close to other ratites, are more closely related to extinct elephant bird, suggesting independent evolution of flightlessness. Tinamous, small, flying birds from South America, are also now considered to be part of the ratite lineage, further complicating the picture.

For more on this See Ratites and Their Evolution Under MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

Evolution of Kiwis

A) Break-up of Gondwana into separate continents; B) The ratite family tree, as you’d predict from the rafting hypothesis; C) The actual ratite family tree

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: DNA analysis has shown that kiwi are part of the Australasian group of palaeognaths, which includes emus and cassowaries. Contrary to popular opinion, kiwi are not closely related to moa. Moa were a separate group which split from the ancestral ratite line well before the common ancestor of kiwi and emus did. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Some biologists have theorised, on the basis of egg size, that the ancestral kiwi was larger than its modern descendants. Eggs the size of a kiwi’s should theoretically be laid by a bird two or three times the size of today’s kiwi. When selection pressures brought the ancestral kiwi down to its present size, the egg failed to shrink with it — for the simple reason that developmental pathways are more difficult to change than a bird’s adult size. If the proto-kiwi was a cassowary-sized bird, then the suggestion that kiwi flew to New Zealand can be discounted, because a bird of that size could not have flown even the narrower early Tasman Sea.

The recent evolutionary history of kiwis is unclear. Given the geological ups and downs New Zealand has experienced in the past, life on this archipelago cannot have been easy — for kiwi or for any other members of the fauna. During the Oligocene, which lasted from about 37 to 23 million years ago, most of New Zealand lay beneath shallow seas. The fragmentation of the landmass into various small swampy islands probably resulted in the extinction of many species and encouraged, by separating populations, the evolution of others, including those of moa, kiwi and wrens.

How Did Kiwis Arrive in New Zealand

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: So, when and how did kiwi come to New Zealand? There are three possibilities. The first is that the kiwi ancestor was already here when New Zealand broke away from Antarctica and Australia some 60 million years ago. This scenario pushes the kiwi’s origin back to the age of dinosaurs, and sidesteps the question of whether the ancestral kiwi could fly or not. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

The second scenario is also unaffected by the flying ability of the ancestor, although it is traditionally seen as the “walking to New Zealand” theory. During the past 50 million years, a succession of islands has risen and sunk along the ridge extending south and east of New Caledonia, through the position of Norfolk Island, and on to the Northland peninsula. While these islands do not seem to have all been above sea level at the same time, it may have been possible for species to have travelled south along with the successive emergences, and so reached New Zealand.

The third possibility requires a flying kiwi ancestor. It is known that flighted palaeognaths existed in the Northern Hemisphere, so perhaps such a bird could also have been present in Australia and could have reached these shores — as have many other birds — long after New Zealand broke away from the rest of Gondwana. Emus, cassowaries and kiwi would then have gone down their own evolutionary paths, the kiwi in the presence of other large birds which were already here — the several species of moa.

In evaluating these options, the fossil record is singularly unhelpful, because the oldest known kiwi fossil (a femur, found in coastal deposits near Marton) is, at about one million years old, far too young to shed any light on the birds’ origins in New Zealand. Present DNA evidence is also inconclusive.

Where Kiwis Still Survive and Even Thrive

Stewart Island is home to New Zealand’s last major population of wild kiwis, with 15,000 to 20,000 birds. Rogan Colbourne, a Department of Conservation scientist with the Kiwi Recovery Programme, told New Zealand Geographic: The Stewart Island population of the southern southern brown kiwis is the strongest and the most dynamic. The call counts there peak at 60 an hour, and we estimate 20,000 birds.” On Stewart Island, kiwis are often seen because they emerge from the bush as night falls to feed on sandhoppers and other small creatures that are found in kelp that has washed up on the sea shore. If you seek them out it is best to arrive early and find a place and sit their quietly and wait for them to come. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Elsewhere in New Zealand, kiwis still survive in fragments of native habitats, some laboriously restored. Colbourne s, a Department of Conservation scientist with the Kiwi Recovery Programme. Kiwis “are certainly in trouble, but not all and not everywhere. The great spots in Kahurangi, the Paparoas and around Arthurs Pass are holding their own. Just. The little spots are safe on offshore islands — we could easily crop 100 chicks every year and transfer them, if there was somewhere else to put them.

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: Reasonable populations have been found in pine forests, for instance. Hugh Robertson, director of the Kiwi Recovery Programme, speculates that kiwi success among pines may be due to lower numbers of mustelids: “There are fewer edible seeds and fruit in pine forests than in native bush, so rats and mice are less abundant. Since small rodents are the main prey for stoats and ferrets, we suspect that their numbers are reduced in exotic forests, and this may allow kiwi to breed more successfully.” [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Waimarino Forest in the central North Island, Tairua Forest on the Coromandel Peninsula and a number of pine forests in Northland all support significant populations of kiwi, but the birds are absent from Kaingaroa, southeast of Rotorua — perhaps on account of its mineral-deficient pumice soils. In pine plantations, farm woodlots, even in gorse and scrub on the outskirts of towns, wild kiwi turn up in surprising numbers in Northland, resolutely surviving but usually glimpsed only in adversity. An unchained dog brings home a kiwi carcass, a possum trap catches what it’s not meant to, a farmer sets fire to a useless piece of scrub and finds it alive with birds, a lawnmowing contractor hits a roadside stump, unearthing a two-egg burrow and sending a kiwi bolting for cover.

Kiwi Characteristics

Kiwis have globular bodies with no identifiable wings or tail. Kiwis have low body temperatures, fur-like feathers, strong legs that allow them to run as quickly as a humans and other physiological features that have led scientists to dub them "honorary mammals."

Kiwis have a number of unique features. They are the only birds with nostrils at the end of their bill. It is no surprise then that Unlike most birds, kiwis have a very keen sense of smell. They have an enlarged olfactory bulb. Their nostrils are used to smell earthworms and other soil organisms that they feed on. The bill helps them to probe and dig out these creatures.

Although flightless, kiwis have a pair of three-inch vestigial wings. Kiwis have large feet and powerful legs which allow them to move quickly through the forest.Their claws and strong powerful legs enable them to fight ferociously if necessary. Most kiwi fighting is done between rival males.

For aerodynamic reasons, the bones of most birds are light and hollow. In contrast, those of kiwi are heavy and filled with marrow. Kiwi skin is tough enough to be made into shoe-leather. Their body temperature, 38°C (100.4°F) is closer to humans than to the temperatures of most other birds, which are in the 39-42° range The long, soft feathers of kiwis look and feel very hair-like and give them a shaggy appearance. The softest feathers are those of the great and little spotted kiwi. These birds were hunted extensively in the 19th century to supply fashion houses with feathers for kiwi muffs. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Kiwis have whiskers at the base of their bill used for touch. This is especially important for these birds because they have small eyes and poor vision. Other characteristics include underdeveloped pectoral muscles. Kiwis are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them), warm-blooded (homoiothermic, have a constant body temperature, usually higher than the temperature of their surroundings). |=|

Kiwi Diet and Feeding Behavior

Kiwis spend majority of their time foraging, and less time moving about, socialising and looking out for predators. Kiwis eat both plants and animals and seem particularly fond of earthworms. They thrust their bill into the ground, gather food, and beat the prey on the ground before they consume it. Their diet of some species primarily consists of invertebrate species, including spiders and worms, which make up 85–95 percent of their intake, with plant material comprising the remainder.

Some kiwi seem to have developed a taste for the large crustaceans, and actively hunt them along the edges of streams and even in the water. They have also been observed eating young eels, frogs, , cockroaches, millipedes, huhu grubs, berries (especially hinau and pigeonwood), seeds, leaves — and 178 species of native worms and 14 introduced ones. Kiwis sometimes do a headstand, kicking their legs up into the air to drive their bill into the soil. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

“Some of the big native worms resemble a length of garden hose, with a diameter to match,” ecologist John McLennan told New Zealand Geographic. “They are powerful and reluctant victims, and often escape after a brief struggle. But once a kiwi gets a good grip on one of them, the tug-of-war can last for several minutes.”

On a kiwi consuming a worm, Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: The bird applies a steady strain and waits for the opponent to yield, because yanking it would tear the worm in two and shorten the meal. Some worms phosphoresce as they are pulled from the soil, illuminating the kiwi’s bill and face with an eerie light. Kiwis appear to get much of water and liquid they need from worms. Those in captivity that a lot of worms hardly ever drink.

While feeding a kiwi's "beak taps the way ahead like a blind person’s cane, and every few steps the bird augers it excitedly right up to the hilt in pursuit of a wriggling morsel. Now and then it pauses to blow the dirt out of its nostrils with a sharp sneeze. Then, with no more than a rustle of ferns, it vanishes, though for a while we can still hear it. Tap! Tap! Jab! Snort! goes the kiwi, the ghost of the forest.

Kiwi Behavior

Kiwis are cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), mainly solitary, terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). [Source: Smitha Gudipati, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kiwis spend the day in their burrows. Kiwis are difficult to see as they come out mostly at night and have acute senses of hearing and move away when they sense something approaching. Most kiwis have a territory of around 15 acres. Single males usually have territories that are twice as large as paired males. Kiwis mark their territories with extremely smelly droppings. Male kiwis announce their claim on a territory with a loud shriek that is repeated several times. Kiwis also make short snorting noises.

Kiwis run with a "wide straddling gait." Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: While other ratites thump the earth with their large, dinosauric feet, kiwi can walk almost silently, their loping trot muffled by fleshy footpads.” Kiwis “are strong, if reluctant, swimmers. Because they are so heavy, and quickly become waterlogged, only the tops of their heads and backs show above the surface. This gives them a clumsy, sinkingtea-kettle kind of look, but below, those huge drumsticks are kicking hard, so kiwi can make good headway even against a moderate current. One bird is known to have crossed the Whanganui River twice. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Kiwis dig burrows like a badger, and their faces bristle with feline whiskers. More than one biologist has noted a rodent-like quality to the birds — they seem more rat than ratite. Kiwi typically emerge from their burrows just after sunset and, like a dog, literally follow their noses searching for food. The long, flexible beak is equipped with a pair of sensitive nostrils at its tip — an adaptation unique to kiwi. Stabbed repeatedly into the soggy world of earthworms and grubs, this remarkable appendage serves as an olfactory underground periscope. In other birds, a sense of smell is of little importance. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Kiwi are not entirely antisocial, however. Male and female maintain a pair bond that lasts for years, if not life, although they do not necessarily cohabit. Often a pair jointly occupy a territory which contains hundreds of burrows, but share the same burrow only 40 per cent of the time.

Kiwi Senses

Kiwis have excellent senses of smell. They can smell creatures below the ground and insert their bills until the dirt reaches their face to get them. The long rictal hairs found at the base of the bill are used for sensing potential prey items at night. When they submerge their bills too deep their nostril become clogged with dirt but they can blow them clear using a special valve in their beaks. Kiwis have distinct ears, acute senses of hearing and are good at detecting high frequency sounds. But their eyesight is very poor. Some have suggested they can not see anything other than what is just a few centimeters (inches) in front of them.

Over evolutionary history, the visual organs of kiwi ancestors have shrunk. Kiwis have smallest visual field reported of any bird species that rely on non-visual cues for foraging purposes. It has been proposed that this adaptation arose due to their nocturnal, forest-floor foraging behaviour, where low light conditions render visual perception less critical. [Source: Wikipedia]

Kiwis rely on remote touch and smell (olfaction) to find prey. Their bills have with sensitive nerve endings towards the tip of their long, narrow, slightly-down-curved bills which are used find prey by touch. They can detect movement or presence of potential prey through vibrations and changes in pressure. The bill-tip sensory organ found at the end of their beak contains mechanoreceptors, such as Herbst corpuscles and terminal cell receptors, found within sensory pits in the bone of the beak tip. These mechanoreceptors are sensitive to the vibrations and pressure gradients soil dwelling invertebrates make underground, allowing kiwi to detect their prey without visual or auditory cues.

Kiwi Communication and Calls

Kiwis are very vocal. Their name derives from the sounds they make, which sound like kee wee wee! This call is often repeated in the dusk and dawn. Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: Calling seems to play an important role in kiwi society, both to delineate territories and to identify individuals. In the early 1980s, Rogan Colbourne, along with radio’s “Bug Man,” Ruud Kleinpaste, made an extensive study of kiwi in Waitangi State Forest. They found that males, the more territorial gender, made 75 per cent of calls, especially during the early part of the breeding season. If two birds ended up close to each other on the edges of their territories, a vocal battle usually resulted, but not normally fisticuffs. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

The male and female calls are quite different. The male North Island brown emits a whole string of brief shrill cries (up to 40) that may run over 30 seconds or longer, and his beak is wide open and pointing skywards while he sounds off. His cry may carry for up to a kilometer. Female calls are quieter and hoarser — those of the North Island brown have been likened to the heaving noise a cat makes before it vomits! Calling is concentrated in the hours following sunset, and is more regularly heard on dark nights.

In their study, Kleinpaste and Colbourne noted quite a vocabulary of sounds among North Island browns. Members of a pair traded contact calls, there was a sniffling sound which accompanied feeding, and nasal grunts were exchanged between feeding pairs. Mewing and purring sounds — the latter carrying for up to 50 meters — were used by courting and mating birds. Sounds associated with aggression included hissing, bill-snapping, squealing and growling.

Kiwi Fighting and Territoriality

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: Kiwi, especially males, are highly territorial birds, occupying and aggressively defending territories which range in size from just a few hectares to over 100 hectares. Loud cries-which can carry several kilometers assert a bird's dominance in an area, and warn off intruders. If vocal threats are ignored, a full-scale fight can ensue, and the combination of sharp claws and powerful feet can tear an adversary apart. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Into my field of view runs a shaggy, pear-shaped ball of feathers propelled by large T rex feet, sniffing and snorting like an agitated hound. It stops to let out another battle cry — a penetrating shriek that makes you want to plug up your ears — then freezes to listen out for the intruder. We hold our breaths against this fierce audio scrutiny, and soon, reassured of its dominance, the creature relaxes and resumes feeding.

Here, in the heart of Kahurangi National Park, the night still belongs to the kiwi. You can hear them calling across the glades: the shrill Crrweeee! of the male and the guttural reply of his larger partner,, both ready to attack anything that blunders into their 25 hectares territory. “They fight like devils,” McLennan tells me. “Put two rival kiwi together and soon you may have only one left alive.”

Their combat is a furious kick-and-tear kind of karate, with high jumps and slashing blows with their sickle claws. Once their kingdoms are established, however, the birds usually resolve territorial disputes by vocal duels, avoiding border scraps altogether. This leaves more time for feeding — for sniffing out beetles or moth larvae from beneath clumps of tussock, or wrestling earthworms out of the ground.

Pound for pound, Colbourne tells me, the little spotted kiwi are the most vicious and bad-tempered. They have the sharpest claws, and use them liberally. All kiwi will put up a fight when cornered, but Stewart Island southern brown kiwis — as large as great spotted kiwi — are particularly notorious. “When you try to get them out of their burrows, they back up against the wall of the burrow and use their feet and claws like hammers. You’re lying there with your hand down the hole, and the earth underneath you shakes as if there was a sub-woofer buried there. Oomp! Oomp! Oomp! You have to synchronise with that rhythm and grab them on the off-beat!”

Kiwi Reproduction and Offspring

In many kiwi habitats the female to male ratio is around 1 to 1.4. Even so kiwi females are largely monogamous. It can be hard to tell young males from females. Even DNA tests can be inconclusive. Because kiwis belong to one of the world’s most ancient group of birds — 60-million-year-old ratites and their genetic material differs from modern birds — scientists often have to wait until the bird lays an egg to be sure.

Kiwis are ground nesters. They lay their eggs in burrows in the ground, or under clumps of grass, rotting vegetation or pine needles. Kiwis often make nesting dens with large amounts of materials. Their nesting sites often have overhead cover, such as crevices or trees with buttressed roots, or are in downed logs, underneath rock formations, and hidden under dense vegetation. The nest of great spotted kiwis is comprised of vegetation and built in burrows, although occasionally nests are exposed.

Chicks are hatched fully feathered and resemble miniature adults. Kiwi chicks have no egg tooth at the end of the bill to help them pierce the shell, and hatching can be difficult, taking up to three or four days. When a kiwi chick hatches a third of its mass is still yoke. For the first two or three days of its life it can not stand because its legs are spread so wide by the big yoke sac enclosed inside its belly. There is sufficient yolk to sustain them for their first week of life. Thereafter they have to provide for themselves, for kiwi parents never feed their offspring. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Enormous Kiwi Eggs

When it comes to eggs the kiwis hold quite a few records. A 2.8-kilograms (six-pound) female brown kiwi lays a 0.8 kilogram (one pound) egg — the largest egg-to-body ratio of any bird. X-rays of pregnant brown kiwis reveals an egg that appears to occupy half of the kiwi's body. The egg-to-body ratio of most birds is 1 to 25. Ostriches, which produced the world's largest eggs at three pounds, have egg-to-body ratio of around 1 to 100 or 1 to 50. The only birds that have a comparable ratios to kiwis are tiny hummingbirds.

According to New Zealand Geographic:. Averaging 400 grams in weight and 125 millimeters in length, the egg represents close to a fifth of the adult body mass. In North Island brown kiwi-which generally lay two eggs in a clutch-the second egg is forming when the first egg is laid. The egg is 65 per cent yolk, compared with 35-40 per cent in most birds. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Egg-laying is a demanding process for kiwi females, who lose considerable amounts of weight after laying each egg. Most females lay one egg and after a brief recovery they develop and lay another egg and then take a rest. Only in rare occasions do they produce three or more eggs in succession. The egg fills up the female’s body to such a degree that she sometimes soaks her belly in puddles of cold water to relieve the pressure and rest the weight.

The kiwi egg takes 34 days to develop, the longest of any bird (most bird eggs takes only one or two days to develop). The egg itself is 60 percent yoke, among the largest yoke-to-egg ratio of any bird. Only birds like the Australian brush turkey and mallee fowls that do not warm their eggs with body heat produce larger yokes. Kiwis eggs also contain a lot of fat.

There are many theories as to why kiwis lay such large eggs, but the general consensus is that kiwis descended from extremely large birds such as moas and their bodies shrunk while their eggs stayed pretty much the same size. Biologists Michael Taborsky and Barbara Taborsky believe that with few predators, before humans arrived, large chicks had a better chance of survival and thus became the "reproductive ideal."

Kiwi Egg Care, Incubation and Parenting

In some species only males incubate the eggs and in others both males and females do so so. Male North Island and southern brown kiwis incubate the eggs for 75 yo 80 days — the longest for a bird — until the chicks hatch. Males warm the eggs almost non stop during incubation period, leaving the nest for only a few hours each day to collect enough earth worms to keep from starving. After hatching males stay with the chicks another two weeks or so until the chicks "get their legs" and are able to run around and collect their own food.

Males take care of the egg warming duties partly because females need to devote all of their energy to producing eggs. The only female kiwis known to share in egg incubating duties are southern brown kiwis on Stewart Island, where the cold and rainy climate requires the female to stay with the egg while the male feeds so the egg embryos don't die of cold.

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: Kiwi were once thought to he among the few birds that don’t turn their eggs during incubation, but Colbourne convincingly dispelled that myth. He replaced an infertile egg with one equipped with five temperature probes. The adult bird never noticed the difference, and continued to incubate the electronic egg. Colbourne found that during incubation the temperature between the warm top and the cold bottom varied by as much as 10°C. The pattern of temperatures recorded by the probes showed that the bird must have been diligently turning the egg. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Among the North Island browns, the male carries out all of the incubation of the eggs, leaving only to go feeding for a few hours each night. After hatching, chicks are often accompanied by a parent for a week or two, and may even share a day burrow with their father. After a fortnight, however, the youngsters are given short shrift. Little spotted kiwi behave very similarly to North Island browns, but the parents allow the young to remain in their territory for up to a year. Young Okarito brown kiwi remain with their parents for at least nine months.

Among the Okarito and great spotted kiwi, the females play a much greater role in the incubation process, regularly taking turns on the egg. In all species of kiwi, brooding males develop a bare brood patch on their chests and bellies to better transfer body heat to the egg. Female Okarito kiwi also develop this patch. When both sexes incubate the egg, it stays warmer, and hatching is typically more rapid-65 to 70 days. The reason the North Island several years and even help to incubate their eggs. This arrangement gives improved safety from predators (while there are no mustelids on Stewart Island, there are large numbers of feral cats) and also saves juveniles from blundering into foreign territories — for in places where predator numbers are low it is another kiwi that is a chick’s greatest enemy. “It’s not just that the resident birds kill the intruder,” Colbourne says. “They feel obliged to tear and shred and pulp it and stomp it into the ground until it’s all mince and feathers.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025