Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

MOAS

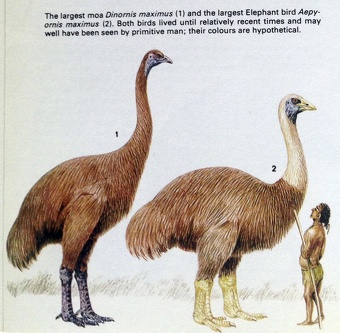

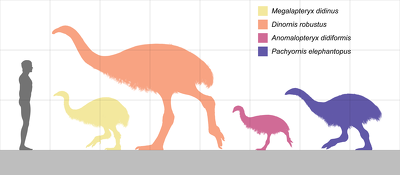

Moas were large flightless birds that looked like ostriches on steroids and are now extinct. They belonged to the order Dinornithiformes and were endemic to New Zealand. There were nine species of them. The largest were about 3.6 meters (13 feet) tall with their neck outstretched and the smallest were about the size of a turkey. Medium size moas stood about 1.2 meters (four feet) tall, about the size of a rhea or cassowary.

Moas by some reckonings were the largest birds that ever existed. Some scientists believe they evolved from flightless bird, perhaps an ancestor of ostriches, that lived in the supercontinent Gondwana before New Zealand broke away 80 to 85 million years ago. Others think they evolved from flying birds that arrived in New Zealand after it broke away and became flightless in New Zealand. The latter view is generally the accepted one today (See Ratites Below).

Moa were ratites, flightless birds with a sternum without a keel (See Below). They also had a distinctive palate. Genetic studies have found that the closest relatives of moas are flighted South American tinamous, once considered a sister group to ratites. Estimates of the moa population when Polynesians settled New Zealand circa 1300 vary between 58,000 and approximately 2.5 million. The word moa is a Polynesian term for domestic fowl. The word moa is a Polynesian term for domestic fowl. The name was not in common use among the Māori by the time of the European arrival, suggesting that the birds it described had been extinct for some time. Traditional stories about moas were rare. The earliest record of the name was by missionaries William Williams and William Colenso in January 1838. In 1912, Māori chief Urupeni Pūhara claimed that the moa's traditional name was "te kura" (the red bird). [Source: Wikipedia]

Claims that moas were the tallest birds ever may be unfounded. Collectors who reconstructed the skeletons often put together the vertebrae of several individuals. These skeletons show the birds standing erect like ostriches which was likely not the case. Moas were mostly forest-dwelling birds that hunched over as they moved through trees and bushes with their head held in more horizontal position than a vertical one. This conclusion is based on the similarities between moa and cassowary skeletons. Cassowaries move through the forests with their necks in a horizontal position.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS AND HUMANS: MEAT, OIL, RANCHING AND WARS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES AND HUMANS: HISTORY, SIDE BY SIDE, ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN CASSOWARIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES OF NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, WHERE THEY LIVE, WHAT THEY'RE LIKE ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS: EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWI SPECIES: NORTHERN, SOUTHERN, SPOTTED, LARGEST, SMALLEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN BROWN KIWI: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KIWIS, HUMANS AND CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KEAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, PLAYFULNESS, INTELLIGENCE, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KAKAPO: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, SAVING THEM FROM EXTINCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOKAKOS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Evolution of Moas

Size comparison of four moa species and a 180 centimeters tall human; From left to right: Megalapteryx didinus, Dinornis robustus (female size), Anomalopteryx didiformis, and Pachyornis elephantopus

Patrick Pester wrote in Live Science: Moa's closest living relatives are a group of South American birds called tinamous. The largest tinamou species is smaller than most domestic chickens, so is minuscule compared to South Island giant moa. Australia's emus (Dromaius novaehollandiae) are the next closest relative, but while these large flightless birds are physically more similar to giant moa, they're still not as big, growing to an average of 5.7 feet (1.75 m) tall. Both of these living relatives also separated from moa a long time ago. [Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, July 18, 2025

"The common ancestor of the moa and tinamou lived 58 million years ago, while the common ancestor of moa and emu lived 65 million years ago.," Nic Rawlence, director of the Otago Palaeogenetics Lab at the University of Otago in New Zealand told Live Science.Rawlence explained that moa and their closest living relatives descended from a group of small flying birds called lithornids. These animals lived around the world and gave rise to different groups that independently lost the ability to fly. As Rawlence puts it, these flightless birds were "filling the job vacancies in the ecosystem left by the extinction of the dinosaurs."

Moa and emu lost flight through a process called convergent evolution, whereby different organisms evolve similar traits. That means, according to Rawlence, that the physiological and developmental mechanisms behind their body plans evolved independently, potentially via different genetic routes.

Ratites

Moas were ratites, a group that embraces all flightless birds that lack a keel (a ridge of bone that extends outward from the breastbone on which flight muscles of flying birds are attached). Ratites are comprised of six extant families and some extinct families. The five families are Aptergyidae (kiwis), Casuariidae (cassowaries), Dromaiidae (emus), Rheidae (rheas), Tinamidae (Tinamous) and Struthionidae (ostriches). The family for the elephant bird is the extinct ratite family Aepyornithidae. The "moa family" belong the extinct Dinornithiformes. Ratites They are mostly large, long-necked, and long-legged, with the exceptions being the kiwi, which is also the only nocturnal extant ratite, and tinamous which can fly. Ratites were previously known as Struthioniformes. The name ratite is derived the birds’ raft raft-like sternum. [Source: Wikipedia, Ellie Bollich, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: The name ratite, from ratis, Latin for raft, refers to the birds’ sternum, which is flat and raft-like, lacking a keel to which flight muscles could be attached. The sterna of flighted birds have a keel to which their large flight muscles are attached, and these birds are sometimes termed carinates (from the Latin carina, a keel). Just to confuse the issue, though, some ratites — the South American tinamous, for example — have a keeled breast-bone and can fly. On the other hand, the kakapo, whose parrot relatives can fly extremely well, have a sternum as flat as that of any kiwi or moa. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

The strongest evolutionary link between ratites lies not in the chest but in the mouth. All ratites, living and extinct, share a similar arrangement of the palate bones in the roof of the mouth, which sets them apart from other birds and is the best evidence of a common ancestry of a group that now includes the tinamous, kiwi, moa, emus, cassowaries, ostriches and South American rheas. Today, some biologists prefer to use the term palaeognath (old mouth) over ratite when referring to this group.

Flightless birds have survived in a terrestrial environment dominated by mammals primarily because they have long legs that allow them to run at great speeds — faster than potential mammal predators. Ostriches, rheas and emus live in open grasslands or semi-desert where there is lot of room to run, Cassowaries are stockier and have shorter legs. They live in tropical forest, where they have no predators.

Evolution of Ratites

It was first thought that ratites shared a common flightless ancestor on the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which later fragmented, leading to the diversification of ratites on different continents. However, modern genetic studies suggest that ratites may have lost the ability to fly independently and the ancestors of living ratites diverged relatively recently, after the breakup of Gondwana. This suggests that the loss of flight occurred in different ratite lineages — an example of convergent evolution, the process by which distantly related animals independently evolve similar traits or features as a result of adapting to similar environments or ecological niches.

Evidence suggests that ratites might have evolved flightlessness multiple times, with different lineages developing similar traits (such as large size, reduced wings) in response to similar environmental pressures. For example, kiwis, despite being geographically close to other ratites, are more closely related to extinct elephant bird, suggesting independent evolution of flightlessness. Tinamous, small, flying birds from South America, are also now considered to be part of the ratite lineage, further complicating the picture.

Fossil evidence suggests that early ratites, like the Paleognaths, were not all flightless. Some had keels on their sternums, indicating they could fly. This implies that the ability to fly was lost multiple times independently as different ratite lineages adapted to life on the ground. The loss of flight may have been driven by factors such as the availability of suitable habitats, the absence of predators, and the advantages of large size for foraging. The exact evolutionary history of ratites is still being actively researched, with ongoing studies using genetic and fossil data to refine our understanding.

Flinders University researchers studying cassowary’s eating, breathing and vocal structures found a surprising link between two vastly different birds in the primitive palaeognath family thought to be each other’s closest relative — the small flighted South American tinamou and the extinct New Zealand moa. In a study published in BMC Evolutionary Biology, researchers from Flinders University analyzed the throat structures involved with breathing, eating and vocalising (the syrinx, hyoid, and larynx) in cassowaries with advanced scanning technologies able to generate 3D image these structures and found they were similar to those of emus, their closest relatives. No surprise there. “What did surprise us though was that despite extensive variation in this region between cassowaries and other primitive living birds, known as palaeognaths, the extinct New Zealand moa and the living South American tinamou were very similar,” said Phoebe McInerney, lead author on the papter and a PhD student at Flinders. DNA analysis also concluded that moa and tinamou are close relatives even though moas were huge and flightless, birds and tinamou are small, flighted partridge-like bird. [Source: Flinders University, January 17, 2020]

Moa Characteristics

Unlike ostriches, emus, cassowaries and rheas, moas possessed no wings or remnants of wing bones. They were the only wingless birds, lacking even the vestigial wings that all other ratites have. The only evidence their ancestors had a wing was the scapulocoracoid bone (a fusion of the scapula (shoulder blade) and coracoid (shoulder) bones), at one point earlier in their evolution, was where the humerus (forlimb) should have attached.

Moa skeletons were traditionally reconstructed in an upright position — like ostriches — to create impressive height, but analysis of their vertebral articulations indicates that they probably carried their heads forward like kiwis or cassowaries. The spine was attached to the rear of the head rather than the base, indicating a horizontal alignment. This would have let them graze on low vegetation, while being able to lift their heads and browse trees when necessary. However, Maori rock art depicts moa or moa-like birds with necks upright, indicating that moa were capable of assuming that position. [Source: Wikipedia]

Some idea of moa vocalizations can be gleaned by studying fossil anatomy. The trachea of moa were supported by many small rings of bone known as tracheal rings. In some species these existed in a trachea that was up to one meter (3.3 feet) long, forming a large loop within the body cavity. Moas are the only ratites known to have tracheal rings, which are found in bird groups, including swans, cranes, and guinea fowl. These rings are associated with deep resonant calls that can travel long distances.

Several examples of moa remains have been found with soft tissues (muscle, skin, feathers) preserved through desiccation after the bird died at a dry site. Most were found in the semiarid Central Otago region, the driest part of New Zealand. Loose moa feathers have been collected from caves and rock shelters in the southern South Island. The preserved leg of M. didinus from the Old Man Range reveals that this species was feathered right down to the foot. This is likely to have been an adaptation to living in high-altitude, snowy environments, and is also seen in Darwin’s rhea, which lives in a similar seasonally snowy habitat. There is evidence of moa feathers being up to 23 centimeters (9 inches) long, and came in a range of colors including reddish-brown, white, yellowish, purplish and dark with white or creamy tips.

Despite the bird's extinction, the high yield of DNA available from recovered fossilised eggs has allowed the moa's genome to be sequenced. About eight moa trackways, with fossilised moa footprint impressions have been found in the North Island, including Waikanae Creek (1872), Napier (1887), Manawatū River (1895) and Marton (1896). Analysis of the spacing of these tracks indicates walking speeds between 3 and 5 kilometers per hour (1.9 and 3.1 miles per hour). In 2019, the first known trackway in the South Island was found in a riverbed at Kyeburn, Otago.

Moa Diet. Behavior and Feeding Habits

Moas were vegetarians, Their beaks were not structured to tear apart meat. Preserved contents of moas stomach show that they had a high fiber diet of mostly twigs and leaves taken from low trees and shrubs. A diet like this requires a large digestive tract to process and its is believed that moas became so big so they could support a stomach large enough to do this. Like many other birds, moa swallowed gizzard stones (gastroliths), which were retained in their muscular gizzards, providing a grinding action that allowed them to eat coarse plant material. This grinding action suggests that moa were not effective seed dispersers, with only the smallest seeds passing through their gut intact.

The diet of moas has been deduced from fossilised gizzards contents and coprolites (fosilized feces) as well as indirectly through morphological analysis of skull and beak, and stable isotope analysis of their bones. The beak of the Heavy-footed moa (Pachyornis elephantopus) was similar to a pair of pruning clippers and could clip the fibrous leaves of New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) and twigs up to at least eight millimeters in diameter.

Moas were terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active mainly during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area),In the near-mammal-less New Zealand, moas filled ecological niche occupied by browsing mammals like antelopes, deer and llamas. Some biologists have argued that a number of plant species evolved to avoid moa browsing. Among these are divaricating plants such as Pennantia corymbosa, which have small leaves and a dense mesh of branches, and Pseudopanax crassifolius (lancewood), which has tough juvenile leaves.

There is evidence of a coevolutionary relationship between moas and the plants that they ate. Plants that moas fed on developed physical and chemical defenses to avoid being eaten. Some plants appear to have mimic the appearance of plants that moas did not eat. The use of spines as a defense against grazing is used among Aciphylla plants, with populations of these plants having reduced spines in areas that would have been inaccessible to moas. The height of moas also contributed to the roles that they played in their ecosystem. Since moas could browse (eat non-grass plants such as bushes and tree parts higher up off the ground) trees and other woody plants needed to grow large enough, quickly enough, so that all of the saplings would not be decimated by the continuously browsing moas. [Source: Keenan Bailey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Moa Reproduction and Eggs

Examination of growth rings in moa cortical bone has revealed that these birds were K-selected, as are many other large endemic New Zealand birds. K-selected refers to species that thrive in stable environments, are well-adapted to high population densities, and focus on a few, large offspring with high parental care and investment. These species typically have long lifespans and populations that remain close to the habitat's carrying capacity. They are often characterised by having a low fertility rates and long maturation periods, taking about 10 years to reach adult size. [Source: Wikipedia]

Moa nesting is often inferred from accumulations of eggshell fragments in caves and rock shelters. There is little evidence of the nests themselves. No evidence has been found to suggest that moa were colonial nesters. Excavations of rock shelters in the eastern North Island during the 1940s found moa nests, which were described as "small depressions obviously scratched out in the soft dry pumice". Moa nesting material has also been recovered from rock shelters in the Central Otago region of the South Island. This included plant material — including twigs clipped by moa bills — used to build a nesting platform. Seeds and pollen within moa coprolites found among the nesting material provide evidence that the nesting season was late spring to summer.

Fragments of moa eggshell are often found in archaeological sites and sand dunes around the New Zealand coast. Thirty-six whole moa eggs exist in museum collections and vary greatly in size (from 1.2 to 2.4 centimeters (4.7–9.4 inches) in length and 9.1 to 17.8 centimeters (3.6–7.0 inches) wide). The outer surface of moa eggshell is characterised by small, slit-shaped pores. The eggs of most moa species were white, although those of the upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus) were blue-green.

A 2010 study by Huynen et al. found that the eggs of certain species were surprisingly fragile, only around a millimeter in shell thickness: "Unexpectedly, several thin-shelled eggs were also shown to belong to the heaviest moa of the genera Dinornis, Euryapteryx, and Emeus, making these, to our knowledge, the most fragile of all avian eggs measured to date. Moreover, sex-specific DNA recovered from the outer surfaces of eggshells belonging to species of Dinornis and Euryapteryx suggest that these very thin eggs were likely to have been incubated by the lighter males. The thin nature of the eggshells of these larger species of moa, even if incubated by the male, suggests that egg breakage in these species would have been common if the typical contact method of avian egg incubation was used."

Extinction of Moas

A popular New Zealand song goes

No moa, no moa

In old Ao-tea-roa.

Can't get 'em.

They've et 'em;

They've gone and there aint no moa!

With the exception of large Haast’s eagles, moas had no natural enemies and had no fear of the early Polynesians who easily hunted them for food and rendered them extinct in a relatively short period of time. Most species of moa were extinct by the early to mid-15th century CE, with their rapid demise occurring around 1440 CE. A few smaller species may have survived until the end of the 17th century when the Europeans first set foot on New Zealand but for the most moas were gone before Europeans arrived.

Remains of the nine moa species, which ranged from 20 to 250 kilograms (44 to 551 pounds), are abundant in early human archaeological sites, indicating they were a major item of the diet immediately after colonization. Shell fragments found at archaeological sites indicate that moa eggs were also widely eaten. At later sites there was more reliance on fish, shellfish, and plants. There is some evidence that humans did not show up in large numbers on New Zealand until around A.D. 1350. If that is the case the demise of moas was even more rapid than previously estimated. [Source: Mark Rose, Archaeology magazine, March 29, 2000]

Moa is a Polynesian word for chicken. The number of moa skeletons found in known Maori food sites is estimated at between 100,000 and 500,000. Moas were trapped, snared, driven into swaps and clubbed to death. Some cultural depictions of moa describe how the moa was best cooked and enjoyed as a food, such as, He koromiko te wahie i taona ai te moa (“The moa was cooked with the wood of the koromiko”). Other old Maori descriptions focus on their extinction — which was seen as sign that moas were metaphor for Māori’s worries about their own extinction especially as a result of disease and deforestation brought by European settlers. This sentiment is perhaps best expressed with sayings such as Huna I te huna a te moa ("Hidden as the moa hid") and "Dead as the Moa" as well as depictions of moas “having a human face and living in a cave,”

The diversity of habitats that the moa could survive in has largely poked holes in theories that the moa extinction could have been a result of habitat loss. Radiocarbon data shows a strong time correlation between the spread of the highly mobile Māori people across New Zealand and plummeting moa populations. Moas appear to have been unable reproduce at the rate fast enough to compensate the rate they were being culled. Polynesian dogs may have eaten moa chicks; Introduced rats could have possibly broken thin-shelled eggs and eaten the contents.

DNA Evidence That Humans Hunted Moa to Extinction

A March 2014 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, an international team of researchers points to humans as the cause of the sudden extinction of all species of moa in New Zealand approximately 600 years ago based on DNA and archeological evidence. [Source: Bob Yirka , Phys.org, March 18, 2014]

Bob Yirka wrote in Phys.org: To find out if the birds were in decline, the researchers performed two types of DNA analysis (mitochondrial and nuclear) on 281 different sets of fossilized bones from four different species. The age of the specimens ranged from 12,966 to just 602 years ago. In so doing they found no evidence of a species in decline. Normally, they note, a species in trouble becomes less genetically diverse as the population dwindles. In the case of the moa, there were no such signs, instead, it appeared the population was healthy and even growing right up to the time that humans first appeared. Two hundred years later, they were all gone.

The researchers note that prior to the arrival of humans, the moa had just one predator — Haast's eagle — that has also gone extinct, likely due to the demise of its main food source. There is no evidence that Haast's eagles increased in population, decimating the moa. The team also notes that large mounds of moa bones have been found at various sites, which also included eggshells. The archeological evidence suggests humans ate moa at all stages of their life, which would of course have made it very difficult for the birds to reproduce. Taken together, the researchers conclude, the evidence indicates that the sole blame for the extinction of the moa lies with early humans who hunted them to extinction.

Scientists wrote in the abstract for the study: We sampled 281 moa individuals and combined radiocarbon dating with ancient DNA analyses to help resolve the extinction debate and gain insights into moa biology. The samples, which were predominantly from the last 4,000 years preceding the extinction, represent four sympatric moa species excavated from five adjacent fossil deposits. Although genetic diversity differed significantly among the four species, we found that the millennia preceding the extinction were characterized by a remarkable degree of genetic stability in all species, with no loss of heterozygosity and no shifts in allele frequencies over time. The extinction event itself was too rapid to be manifested in the moa gene pools. Contradicting previous claims of a decline in moa before Polynesian settlement in New Zealand, our findings indicate that the populations were large and stable before suddenly disappearing. This interpretation is supported by approximate Bayesian computation analyses. Our analyses consolidate the disappearance of moa as the most rapid, human-facilitated megafauna extinction documented to date.” [Source: Extinct New Zealand megafauna were not in decline before human colonization, Morten Erik Allentoft, PNAS, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1314972111]

Company That De-Extincted Dire Wolves Wants to Do the Same with Moas

In July 2025, Colossal Biosciences, the Texas-based biotech company that claims to have brought Ice-Age dire wolves, said it had formed partnership with filmmaker Sir Peter Jackson and Indigenous partners to bring back the 3.6-meter (12-foot) -tall South Island giant moa and other moa species. However, experts say that dire wolves were never truly resurrected, and that moa will be even harder to de-extinct. [Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, July 18, 2025

Patrick Pester wrote in Live Science: The new project will be coordinated by the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, a joint venture between the main Māori tribe (iwi) on the South Island of New Zealand and the University of Canterbury in Christchurch. It's a multifaceted project that aims to combine traditional Māori knowledge, wildlife conservation and genetic engineering-driven de-extinction. However, the project has already come under fire. Critics have highlighted that some Māori iwi oppose de-extinction, while several scientists have argued that genetically modifying living animals can't bring back lost species. The scientific criticism is similar to the commentary after Colossal unveiled its "dire wolves" — a species that went extinct more than 10,000 years ago.

Colossal's "dire wolves" are genetically modified gray wolves (Canis lupus) with 20 gene edits. The company claims they are dire wolves (Aenocyon dirus) because they have some observable traits identified in the dire wolf genome, such as increased size and a white coat. However, genetically, they're still mostly gray wolves. The same will be true for the living animal Colossal modifies for the moa project — but for moa, it's even more complicated.

"The common ancestor of the moa and tinamou lived 58 million years ago, while the common ancestor of moa and emu lived 65 million years ago," Nic Rawlence, director of the Otago Palaeogenetics Lab at the University of Otago in New Zealand and a critic of the moa plan, told Live Science. "That’s a lot of evolutionary time." To put that in context, dire wolves only split from modern wolf-like canids — the group that includes gray wolves — around 5.7 million years ago (or even more recently at 4.5 million years ago, according to a recent preprint involving some of Colossal's scientists). That means moa had a lot more time to evolve unique traits.

Moa and emu lost flight through a process called convergent evolution, whereby different organisms evolve similar traits. That means, according to Rawlence, that the physiological and developmental mechanisms behind their body plans evolved independently, potentially via different genetic routes, which poses a challenge when it comes to bringing moa back. "Genetically engineering specific genes in an emu to match a moa could have dire developmental consequences given this independent and convergent evolutionary history," Rawlence said.

Plan to De-Extinct Moas

Patrick Pester wrote in Live Science: Before Colossal begins creating its modern-day moa, the company aims to sequence and rebuild the genomes of all nine extinct moa species, while also sequencing high-quality genomes of their closest living relatives. This will allow Colossal to identify the changes that led to the moa's unique traits, including their large body size and lack of wings, according to Colossal's website. [Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, July 18, 2025]

The researchers will then use primordial germ cells, the precursors of sperm or egg cells, from living species to "build a surrogate bird" and make genetic changes to create birds with moa traits. The company needs both male and female surrogates to carry the sperm and egg of their "moa," to then produce the genetically modified offspring.

Colossal's website states that emus' larger size makes them a more suitable surrogate than tinamous. However, details on this part of the process are limited. Shapiro told Live Science that they were "still in the process of selecting the surrogate species for moa de-extinction." Emus lay large green eggs, around 5 inches (12 cm) long and 3.5 inches (9 cm) wide. Still, that's nothing compared to a South Island giant moa egg, which were 9.5 inches (24 cm) by 7 inches (17.8 cm). "A South Island giant moa egg will not fit inside an emu surrogate, so Colossal will have to develop artificial surrogate egg technology," Rawlence said.

Colossal briefly mentioned artificial eggs during its moa announcement, but didn't provide details on this part of the process. Live Science asked Colossal whether they could explain how Colossal will hatch a South Island giant moa. "Our exogenous development team is exploring different strategies for artificial egg incubation, which will have application both for moa de-extinction and bird conservation work," Shapiro said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025