Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

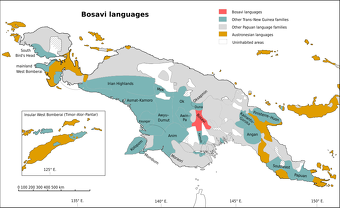

GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU

The Great Papuan Plateau is a karst plateau located in the Southern Highlands, Hela, and Western provinces of Papua New Guinea. The upper stretches of the Kikori and Strickland rivers border it to the east and west, respectively. The Karius Range, the southern edge of the highlands, borders it to the north and includes Mount Sisa (2,650 meter) and Mount Bosavi (2,507 meter).

The eastern part of the plateau, east of the Sioa River, covers about 525 square miles (1,360 km²) and had a sparse population of 2,100 people in 1966, according to the government census. These people speak at least five different languages. The dominant ethnic groups in this region are the Bosavi, the Hawalisi, and the Onabasulu. Further west are the Etoro, Bedamuni, and Sonia peoples. In general, these groups practice swidden agriculture, exploiting taro.

The original inhabitants of the area are unclear due to a lack of evidence. According to the Bosavi people, they have always inhabited the plateau. The relationship between the various ethnic groups and languages remains unclear. The Great Papuan Plateau has petroleum resources, and a pipeline from the plateau to Daru is under construction. In 2006, the Great Papuan Plateau was included on a tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites for its well-preserved natural systems and culturally significant sites.

Australian colonial patrol officers Jack Hides and Jim O'Malley were the first Westerners to visit the Great Papuan Plateau. They led a patrol from the Strickland River to the Purari River in 1934 and 1935. They traveled up the Strickland River by canoe and then continued up the Rentoul River. They left their boats about five miles (8 km) below the confluence of the eastern and western branches of the river. They continued on foot along the south side of the river and traveled for several days without seeing any people or signs of habitation. They then camped at the confluence of the Sioa and Rentoul rivers, where they could see three longhouses and their inhabitants on the opposite side of the valley, who seemed to take no notice of the explorers. The next morning, Hides was threatened by a group of natives who had crossed the river during the night. He escaped but continued to encounter unfriendly natives and was forced to open fire on an ambushing group, killing one to three people. Eventually, the patrol passed north of the Karius Range.

In March 1936, Ivan Champion and Richard Archbold flew over the northern foothills of Mount Bosavi to plan an upcoming expedition from the Bamu River to the Purari River. In response to this incident and the subsequent expedition a few months later, the Bosavi people fled their longhouses and camped in the forest. In 1938, the government opened a station at Lake Kutubu to further explore the highlands. This facilitated the trade of new materials from the east, which the people of the plateau had not experienced through their established trading routes to the south. World War II delayed the planned exploration. In the meantime, a severe measles epidemic greatly reduced the populations of the Etoro and Onabasulu peoples. In 1953, a second administrative patrol led by C.D. Wren came to the plateau to escort a team of petroleum geologists. The first missionaries arrived in 1964. One of them, a Seventh-day Adventist, stayed with the Onabasulu people until they found out that the practice forbade eating pork and forced him to leave. That same year, UFM International arrived in the Bosavi area to build an airstrip for a mission station and recruited local workers for the project.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Etoro and Their Unusual Sex Practices

The Etoro, or Edolo, are a tribe and ethnic group of Papua New Guinea. Their territory comprises the southern slopes of Mt. Sisa, along the southern edge of the central mountain range of New Guinea, near the Papuan Plateau. They are well known among anthropologists because of ritual acts practiced between the young boys and men of the tribe. The Etoro believe that young males must ingest the semen of their elders to achieve adult male status and to properly mature and grow strong. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 3,400 and 75 percent were Christians. In 2009, the National Geographic Society reported an estimation that there were fewer than 1668 speakers of the Etoro/Edolo language.

O'Neil and Kottak agree that most men marry and have heterosexual relations with their wives. The fear that heterosexual sex causes them to die earlier and the belief that homosexual sex prolongs life means that heterosexual relations are focused towards reproduction. R.C. Kelly (1976) stated that Etoro boys are inseminated by oral intercourse by a single inseminator from about the age of ten until he is fully mature and has a manly beard. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin, September 2004]

The Etoro tribe lives in one of the least populated tribes in Papua New Guinea and consists of around 400 people.Anirudh Bellani and Ana Lucia Moreno wrote: The people of the Etoro tribe are fully excluded from the modern societies in Papua New Guinea. They believe that it is better to keep away from the modern society and have no communication with anyone outside of the tribe. Due to this, they believe that they should grow their own crops and build their own shelter. Newcomers are not allowed into the tribe unless they are chosen by the tribe leaders for the purpose of the ritual. [Source: “The Life Of A Boy Living In The Etoro/Sambia Tribe” by Anirudh Bellani & Ana Lucia Moreno onepersonintheworld

Etoro Homosexual Culture

Anirudh Bellani and Ana Lucia Moreno wrote: Being homosexual is completely normal for the Etoro people as they believe it gives them additional force. Due to this, the birth rate amongst the Etoro people is very low. Because of this, the people of the Etoro tribe usually take women from other neighboring tribes in order for them to keep building more families. They also take children from other tribes to raise them as theirs. They do this to replace the children that have died because of the poor health conditions in the Etoro tribe so that they can keep the population at a steady rate. [Source: “The Life Of A Boy Living In The Etoro/Sambia Tribe” by Anirudh Bellani & Ana Lucia Moreno onepersonintheworld

In this tribe, men and women don’t live together because it is not common for them, they are used to homosexuality. They don’t believe women and men are meant to be a couple and stay together. This is different from modern traditions in Papua New Guinea because it is a tradition that has been followed by the Etoro tribe for many generations. Due to this, the people of the Etoro tribe are born into the belief that they are forced to be homosexuals. Since it a tradition that has been followed for decades, the Etoro people believe that they should keep following it in order to show respect to the tribe elders and tribal leaders.

For 100 days in a year Heterosexuality is allowed. There is no real significance to these 100 days and they are mostly used in order to keep the population higher. Normally, the men of the tribe are assigned a female partner to have intercourse with in order to have babies. If the child is a girl, the man looses his honor and the child is seen to have no significance in the tribe. All of this must occur outside of the common area where the Etoro people live because they believe that heterosexuality is disrespectful to their tribe leaders and to their old traditions. Usually, the tribe members go out of town to perform these acts since it is a sin to them to commit it anywhere near their crops or society. During this time, if a woman does not get pregnant she is accused of stealing the force from the man. There are also consequences for the women who enjoy sexual intercourse too much, they are labeled as witches and are accused of stealing force from their husband.

To the Etoro people, the semen-drinking ritual is a regular process that every teenager is forced to go through. The ritual consists of young boys who are forced to drink the semen of the elder people in the tribe every day for ten years. This is done in order to show that the transition from childhood into adulthood for the young boys in the tribe.The ritual starts at the age of 7 and ends at the age of 17. They believe that the start of their teenage life is at age 7 and the end of their teenage life is at age 17. The semen symbolizes the force which their ancestors have blessed them with so that they can honor their family and fight for their tribe. This ritual is a tradition that has been followed for many years in the tribe. For the people of the Etoro tribe, this rites of passage ritual is something that all boys must go through to complete the stages of childhood and enter adulthood. This ritual has been a part of the Etoro tribe traditions for a very long time and every boy is required to go through the process.

This specific ritual is only for the boys of the tribe. In the Etoro tribe, women are not valued. For women, the life force comes after sexual intercourse. If they don’t become pregnant after that, they are seen to waste the force which comes with different punishments. The tribe leaders are usually in charge of choosing young boys to impregnate these women. The participation in this ritual is mostly done by boys. However the boys are told to have intercourse with the woman in order to give the woman energy. The role of the boy is to drink the semen of the older men in the tribes for 10 years in order to show maturity and show the transition from becoming a boy to a man.

Bahinemo

The Bahinemo are small group who live in the Hunstein forest in northwest Papua New Guinea.

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 1,400 and 90 percent were Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent. [Source: Joshua Project]

The languages are a small family of closely related languages of northern Papua New Guinea. The languages are: Bitara (Berinomo), BahinemBahinemo o (Gahom), Nigilu, Wagu, Mari, Bisis, Kapriman (Sare), Watakataui and Sumariup. They are classified among the Sepik Hill languages of the Sepik family. [Source: Wikipedia]

Up until the 1960s the Bahinemo had no word for themselves or their people. With encouragement by missionaries they selected Bahinemo, which means "our talk." According to Edie Bakker, the daughter of these missionaries, "Ask a Hunstein forest resident today if he speaks Bahinemo, and we will say yes. Ask if he is Bahinemo, and he might say no." [Source: "Return to Hunstein Forest", Edie Bakker, National Geographic, February 1994]

By the 1960s the Bahinemo had given up revenge warfare. They agreed with the other tribes in the Hunstein forest that there would be no fighting. But th migration from the the mountains to the lowlands nearly wiped them out. In one eight year period not one of 23 children survived past infancy. Most died from malaria, a disease rare in the highlands.

The Hunstein Forest is one of Papua New Guinea's most pristine rain rainforests. Named after a German explorer, it encompasses the swampy lowlands near the Sepik river and the misty cloud forests of the Hunstein mountains. Herons, cormorants, egrets, parrots, crocodiles, cassowaries and clouds of butterflies make their home there. Plant life includes lianas with 15 foot strings of flowers, palms, bromelaides and huge trees. Because the Hunstein forest is so dense and swampy in the Hunstein region, most people get around by rivers. Those who can afford them have long boats with outboard motors, those who can't afford them use dugouts made from the trunk of a single tree.

When Bakker returned to the Hunstein forest after a 20 year absence she said it seemed little had changes except most wore Western clothing and had Western names. "Members of my peer group looked too old to be in their 30s. The men I grew up with had worn faces and serious eyes. Some of the women were grandmothers." Bawi, one of her friends, had to stop and count how many children she had. "Bawi's world," Bakker explained, "is not governed by numbers or schedules. Some things are constant: the sun, the rain, the incessant spread of vegetation. Other happen unpredictably: children, wild game, thunderstorms, malaria, love, death. People do not plan, cause, or control any of it.

Bahinemo Life and Culture

In the 1960s the Bahinemo lived in small settlements grouped around the traditional men' cult house. Traditionally groups of three or four families ventured into the forest to hunt pigs and cassowaries with bows strung with bamboo fibers. They also gathered fruits and nuts and subsisted on starchy pulp of the sago palm, the staple of their diet. For additional protein they hunted catfish with spears. In the 1960s the Bahinemo used to stay in the forests for weeks at a time, now they only go for days at a time. They trade carvings and crocodile skins for kerosene lamps, matches, metal axes, knives, spoons and western clothing.[Source: "Return to Hunstein Forest", Edie Bakker, National Geographic, February 1994]

The Bahinemo refer to good friends as "tied vines." There is no word for "hello" in the Bahinemo language. A friend who returns after a long absence is welcomed with "You're here." The polite reply is "I'm here." According to Bakker the Bahinemo marry for love. Men move from village to village — "making the long walk" — for marriage or economic alliances. Men sometimes take a second wife but it is considered selfish.

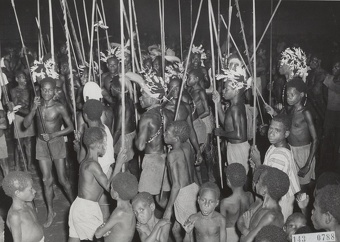

For entertainment Bahinemo of all ages gather to chants and sway rhythmically in an all night get together call a sing-sing. During weddings women in grass skirts dance around a teenage bride who remains covered by a piece of cloth until the groom family pays the an agreeable bride price. Later relatives of the bride and groom face off against one another in a mock battle.

Cinnamon comes from the bark of a rain forest tree which grows wild in the forest. The Bahinemo like to peal the bark and sniff it as a perfume. The foot long nests of the giant moth are harvested for making cloth; the larvae are roasted and eaten.

Bahinemo, the Rain Forest and Logging

Much of the flora in the Hunstein forest has yet to be catalogued. It is estimated that perhaps 10 percent of the plant life is new to science. The Bahinemo travel in three distinct groups in the forest. The hunters lead the party. Behind them men clear the trail with machetes for the women in children in the final group. Bakker was traveling in the middle group. When she noticed one of the men turning leaves she asked him why he was doing this. "The men ahead must have speared a pig," he said with a smile, "We want it be a surprise for the women that we will have will have fresh meat tonight."

Some 97 percent of the land in Papua New Guinea is owned by indigenous land owners. Of this over three quarters is covered with tropical rain forest. With supplies of tropical timber starting to decline in Malaysia and Indonesia many logging companies are starting to negotiate with the Papuan tribes for the timber rights to their land. [Source: "Return to Hunstein Forest", Edie Bakker, National Geographic, February 1994]

The Bahinemo, Bakker says, think of wealth in terms of personal alliances , not profits. They aim for friendship and hope to make some money in the process. They unfortunately employed this strategy when foreign timber companies asked for the rights to harvest timber on their land. "The forestry department said they wanted it, so I'll have to give it to them, won't I?" said one women. The Bahinemo rejected environmental advocates who tried to dissuade from handing over the timber rights because the advocates addressed them in English not Bahinemo.

The Bahinemo see trees as their only real source of income. They covet things like outboards motors for their boats, cassette players, clothes, camping gear and a decent education for their children, and to acquire these thing by selling carvings and crocodile skins takes years.

By their standards the Bahinemo stand to make a lot of money, but the logging companies will make much more. As it stood in the 1990s they got paid US$40 for an average tree, which on the international market sold for US$2,750. Environmentalists hope that at least the forests will be selectively cut, but it is not exactly clear what is going to happen. They loggers have offered the Bahinemo a bonus for clearing the land "only one time."

Bahinemo, Modern Life and Tourism

Bakker worries about what will happen to the Bahinemo. "Not just their outer culture," she says, "what they eat, what they wear — but more devastatingly their inner culture. Who they are as people, how they approach life." Because the government has trouble getting vaccines to the remote forests children still die of diseases like whooping cough. Mothers drown their sorrows by wailing and the babies are often buried in cardboard boxes. [Source: "Return to Hunstein Forest", Edie Bakker, National Geographic, February 1994]

The Bahinemo consider tourism to be evil. "Tourists bring beer," said one village head man, "We have enough problems with alcohol as it is. It has made our teenagers stop listening to us and is tearing up the families. The last thing we need is a steady stream of beer."They also find dancing for tourist groups to be demeaning. When Bakker asked a dancer what he was chanting, he said, "They are telling the spirits, "We shouldn't do be doing this. We shouldn't be doing this. We only do it for the tourists, to make a lot of money.'"

The Bahinemo generally don't like to hike to the upper reaches of the Hunstein mountains. They have no clothing to protect them from temperatures above 55̊F. Westerners generally have trouble with the leaches there. On the subject of mountain climbing one Bahinemo told Bakker: "You know what's wrong with you white people? You're never satisfied getting to the forehead of a mountain — you think you have to get to the top of the crown! You tell your boss that in our country it makes no difference whether something sits on your forhead or on your crown — it still is the top of your head."

Kaluli

The Kaluli inhabit the dense rainforests surrounding Mount Bosavi, on the Great Papuan Plateau in Papua New Guinea’s Southern Highlands. Also known as the Bosavi, Orogo, Waluli, and Wisaesi, they form one of four closely related Bosavi language-clans, collectively called Bosavi kalu (“men of Bosavi”). Of these, the Kaluli are the most numerous and most extensively documented by anthropologists and missionaries. Although increasingly in contact with the outside world, the Kaluli continue to live much as their ancestors did — cultivating their gardens, hunting in the forest, and preserving a worldview that celebrates the sounds, spirits, and stories of the Bosavi rainforest. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The name Kaluli itself means “real people of Bosavi”. Estimates of their population range from about 2,000 to 4,000, though some sources suggest as many as 12,000. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 3,700. They numbered approximately 2,000 people in 1987 and 1,200 in 1969. Their population declined sharply after epidemics of measles and influenza in the 1940s and has never fully recovered due to continued high infant mortality and periodic outbreaks of disease.

The homeland of the Kaluli lies along the northern slopes of Mount Bosavi, between the Isawa and Bifo rivers at altitudes of about 900 to 1,000 meters (2,950 to 3280 feet). The region is covered by thick rainforest, interlaced with clear streams and home to abundant bird and animal life. Temperatures remain constant year-round, with a long dry season from March to November and torrential rains from December to February.

See Separate Article: KALULI (BOSAVI): HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

Western Province

Western Province in southwestern Papua New Guinea embraces coastal areas, the Fly River basin and some highland areas in the north. It borders the Indonesian provinces of West Papua and South Papua. Its capital is Daru. Tabubil is the largest town in the province. Other major settlements include Kiunga, Ningerum, Olsobip, and Balimo.

Western Province is the largest province in Papua New Guinea by area, covering 99,300 square kilometers (37,911 square miles). Several large rivers run through the province, including the Fly River and its tributaries, the Strickland and Ok Tedi rivers. Lake Murray, the largest lake in Papua New Guinea, is also in Western Province. The Tonda Wildlife Management Area, located in the southwestern corner of the province, is a wetland of international importance and the largest protected area in Papua New Guinea.

Much of Western Province's flora and fauna resemble those of northern Australia. The flora includes eucalyptus, melaleuca, acacia, and banksias. Fauna includes wallabies, bandicoots, goannas, coastal taipans, and mound-building termites. : The drier southern regions have eucalyptus and melaleuca savannas, such as the Trans-Fly savanna and grasslands, which support large populations of birds, wallabies, and introduced deer. Dense rainforests are located to the north. The dry season is from July to November, while the wet season is from December to June. Sago cultivation dominates the wetter north, while yam cultivation dominates the drier south.

According to the 2011 census, the population of Western Province was 201,351 people residing in 31,322 households. Of these, 79,349 people were recorded in the Middle Fly district, 62,850 in the North Fly district, and 59,152 in the South Fly district. The average household size across the province was 6.4. The Ok Tedi Mine is the province's primary economic activity. Initially established by BHP, it has been the subject of considerable litigation by traditional landowners regarding environmental degradation and royalty disputes. It is currently operated by Ok Tedi Mining Limited (OTML).

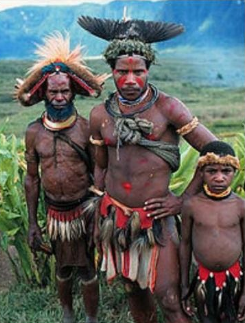

Some of the tribes of western Papua New Guinea living in the frontier region near the Indonesian border have some rather unsettling customs and practices. Drums for example are made from python skin glued on with human blood. The green tree python is the python of choice. The men in some tribes wear finger-size tubes through the nostrils of their noses. During a long and bloody puberty rite initiates in these tribes have the skin between the inside of their nostrils pierced. In some villages, headaches are cured using the "kill pain with pain" method — burning sticks are place on the sufferers forehead. In some cultures when a man dies his body is plucked of all hair and his family hangs out at the body for days — touching it and then themselves in a sign of respect. Later the body is put on a platform to decompose. After that the bones are placed in a bag which are hung outside his family’s house.

Ninggerum

The Ninggerum people live in Papua New Guinea's Western Province, with lands historically extending across the border into South Papua (formerly part of Irian Jaya) in Indonesia. Also known as Kai, Ninggiroem and Ninggirum, they are known for their traditional language (Ninggera), therapeutic knowledge and animist-Christian religious beliefs. The Ninggerum are also associated with a town and rural local-level government (LLG) called Ningerum, which is located on the Kiunga-Tabubil highway. [Source: Google AI]

When first contacted by Westerners, the Ningerum had no single name for themselves; instead, each group identified by its local clan name. The term Ningerum was introduced in the 1950s by Dutch colonial administrators, adapted from the Muyu word Ninggiroem (or Ninggirum), referring to closely related groups who speak mutually intelligible dialects of the same language. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Ninggerum, Kativa population in the 2020s was 11,000. In the 1990s, there were about 4,500 Ningerum people. Over 3,300 lived in Kiunga District (Papua New Guinea) and about 1,000 lives in Kecamatan Mindiptana in what was then Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Some Ningerum have migrated to Daru, Port Moresby, Merauke, and other urban centers. The population density in the 1990s ranged from 7 persons per square kilometer in the south of their territory to less than 2 in the north. At the time of Western contact, the population may have reached 6,000, but the region suffered population decline following numerous influenza epidemics in the 1950s and 1960s. ~

See Separate Article: NINGERUM PEOPLE OF CENTRAL NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

Muyu

The Muyu live mainly in the interior of New Guinea in South Papua province, just south of the central mountains. The name Muyu is taken from the Muyu River, a tributary of the Kao River, itself a tributary of the Digul River. The term “Muyu” has two likely origins. One traces to the arrival of Catholic missions in 1933, when Father Petrus Hoeboer heard local residents refer to the western and eastern sections of a river as ok Mui (“Mui River”). This name, frequently repeated to the Dutch, gradually evolved into Muyu. A second explanation comes from an earlier encounter in 1909, when Dutch explorers traveling up the Digul and Kao rivers met members of the Kamindip subgroup, specifically the Muyan clan. Introducing themselves as neto muyannano (“we are Muyan people”), they provided the name that was later recorded as Muyu and applied to the wider group. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

The Muyu originally inhabited the hilly country between the central highlands and the plains of the south coast. Their territory today is bounded by Papua New Guinea to the east; the Kao and Digul rivers and Merauke Regency to the south; the Star Mountains to the north; and Boven Digoel Regency to the west. The region extends roughly 180 kilometers (110 miles) and covers about 7,860 square kilometers (3,035 square miles), with a width of 40–45 kilometers (25 to 18 miles). The Muyu language is spoken throughout the area, along with the Ninati and Metomka dialects. The landscape is generally hilly, ranging from 100 to 700 meters in elevation. The reddish-brown soils are relatively infertile, contributing to periodic food shortages and historically high mortality. There is no clear wet or dry season in the Muyu area. It rains a lot of the time. The average rainfall is between four and 6.5 meters (13 to 21 feet) per year, depending on the location in the area.

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project in Indonesia in the 2020s the South Muyi population was 2,000 and the South North population was 2,000. In 1956 the Muyu population was estimated at 12,223, with the average population density being three persons per square kilometer. In 1984, dissatisfaction with conditions in their homeland led roughly 7,000 Muyu to flee across the border into Papua New Guinea. By 1989, a few thousand had returned to Papua, with some resettling in the Merauke region on the south coast. Traditionally highly mobile, the Muyu have long migrated in search of better economic opportunities. Today, a large number continue to live in Papua New Guinea’s Western Province as refugees.

See Separate Article: ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025