Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

CHIMBU

The Chimbu live in mountainous Chimbu Province in the Chimbu, Koro, and Wahgi valleys in the central highlands of Papua New Guinea. Also known as Kuman and Simbu, they are an ethnic and linguistic group, not traditionally a political entity. Most people living in the Chimbu region identify themselves first and foremost as members of particular clans and tribes; they tend to only identify themselves as "Chimbus" when they are among non-Chimbus. The term Chimbu was given to them first Australian explorers in Chimbu region in the early 1930s. The name is based on the word simbu — an expression of pleased surprise in the Kuman language — exclaimed by the people when they first encountered the explorers.[Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Chimbu have traditionally lived in a dispersed settlement pattern, with men living separately from women in men's houses. Their primary subsistence crop is the sweet potato, and pigs are central to ceremonial exchange. The Chimbu famously paint their bodies to resemble skeletons for ceremonial dances, a tradition rooted in warding off enemies or monsters.

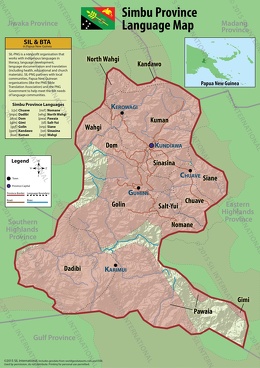

Language: Chimbu speak Kuman and related dialects (SinaSina, Chuave, Gumine) of the Chimbu–Wahgi languages, which are part of the Central Family of the East New Guinea Highlands group of Papuan languages. They are sometimes included in the Trans–New Guinea scheme of language and have linked to the Engan languages in a Central New Guinea Highlands family. In 1994, it was estimated that 80,000 people spoke Kuman, 10,000 of them monolinguals; in the 2000 census, 115,000 people reported speaking Kuman, but few were monolinguals. Ethnologue reported 70,000 spoke Kuman as a second language in 2021. [Source: Wikipedia]

Kuman is a subject-object-verb (SOV) language. Chimbu–Wahgi languages have contrastive tone — meaning pitch is used to distinguish between different words like that of tonal language like Mandarin Chinese. Several of the Chimbu–Wahgi languages have uncommon lateral consonants. Besides the typical /l/, Kuman has a "laterally released velar affricate" which is voiced medially and voiceless finally (and does not occur initially).

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Simbu (Chimbu) Province and Where Chimbu Live

Chimbu, also spelled Simbu, is a province in the Highlands Region of Papua New Guinea. It has an area of 6,112 square kilometers (2,360 square miles) and had a population of 376,473 in 2011 according to the census taken at that time. Approximately 180,000 people lived in Chimbu Province in the 1990s. The capital of the province is Kundiawa. Mount Wilhelm, the tallest mountain in Papua New Guinea is on the border of Eastern part of Simbu and the Western part of Madang Province.

Chimbu is located in the central highlands cordillera of Papua New Guinea. It shares geographic and political boundaries with five provinces: Jiwaka, Eastern Highlands, Southern Highlands, Gulf and Madang. It is a significant source of organically produced coffee. Otherwise, it is has limited known natural resources and is hampered economically by very rugged mountainous terrain. The economic progress of the province has been slower than some other highlands provinces.

The homeland of the Chimbu is located in the northern part of Chimbu Province in the Central Cordillera Mountains of New Guinea around the coordinates 6° S and 145° E. The Chimbu live in rugged mountain valleys between 1,400 and 2,400 meters (4,595 to 7,875 feet) above sea level. The climate there is temperate and the average annual precipitation is between 250 and 320 centimeters (100 and 126 inches). The Chuave and Siane live to the east, and the Bundi live to the north in the upper Jimi Valley. The Kuma (Middle Wahgi) people, who live to the west, are culturally very similar to the Chimbu. South of the Chimbu, in the lower Wahgi and Marigl valleys, live the Gumine peoples. Farther south are the lightly settled lower-altitude areas of Pawaia and Mikaru (Daribi) speakers. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

More than one-third live of the people in Chimbu Province live in the traditional homeland areas of the Kuman-speaking Chimbu. In most of the northern areas of the province, population densities exceeded 150 persons per square kilometer in the 1990s, and in some census divisions population densities at that time exceeded 300 persons per square kilometer. The population of the province has more than doubled since the 1990s. ~

Chimbu History

Relatively little very old archaeological evidence has been found in Chimbu area itself, but data from other highland regions indicate that the area has been occupied for as long a 30,000 years, with agriculture possibly developing 8,000 years ago. The introduction of the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) about 300 years ago enabled the cultivation of plentiful amounts of food at higher altitudes, subsequently increasing the population of the area. According to oral traditions, the Chimbu originated in Womkama, in the Chimbu Valley. A supernatural man chased away the original couple's husband and fathered the ancestors of the current Chimbu tribal groups. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The first recorded contact between the Chimbu and Europeans occurred in 1934 when an expedition led by gold miner Michael Leahy and Australian patrol officer James Taylor passed through the area. Soon afterward, an Australian government patrol post and Roman Catholic and Lutheran missions were established. The initial years of colonial administration were marked by efforts to curtail tribal fighting and establish administrative control in the area. Limited government resources and staff made achieving this goal difficult. By the beginning of World War II, only a tenuous peace had been imposed in parts of Simbu.

Following World War II, the Australians continued their efforts to extend and solidify administrative control. Local men were recruited as laborers for coastal plantations, and coffee was introduced as a cash crop. The establishment of elected local government councils after 1959 was followed by the area's representation in a territorial (later national) legislative body and the creation of a provincial legislature. Local tribal politics remain important, and tribal affiliation greatly influences participation in these new political bodies.

Chimbu Religion

Modern Chimbu are predominantly, with Protestant Christianity being the most prevalent. Around 99 percent of people in the Chimbu region are Christian according to Mission Infobank and Joshua Project. About 96 percent of the population of the region identified as Christian in the 2011 census according to the U.S. Department of State. Many traditional beliefs, particularly those concerning spirits, sorcery, and their connection to illness, persist alongside modern Christian ones. Traditional practices and beliefs have been modified or blended with Christian teachings, but they continue to influence local life. [Source: Google AI]

The indigenous Chimbu religion did not have an organized priesthood or formal worship practices. The sun was considered a significant fertility spirit. Supernatural beliefs and ceremonies focused on appeasing ancestral spirits, who were believed to protect group members and contribute to the general welfare of the living if they were placated through the sacrifice of pigs. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Although Christian beliefs have modified traditional beliefs, many Chimbu still believe that after death, one's spirit lingers near the place of burial. Deaths caused by sorcery or war that go unavenged result in a dangerous, discontented spirit that can cause great harm to the living. Chimbu stories are full of accounts of deceiving ghosts. ~

Chimbu Family, Marriage, Men and Women

Traditionally, Chimbu men lived apart from their wives in communal men’s houses, joining them and their children mainly at mealtimes. Today, married couples increasingly share a single house. In polygynous marriages, each wife maintains her own house and gardens. The basic productive unit is the man and his wife or wives, though related men often cooperate in fencing and cultivating adjacent plots. Households frequently visit one another for short stays, reinforcing kinship ties. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The division of labor remains largely based on gender. Men cut trees, till soil, dig ditches, and build houses and fences, while women handle most gardening, childcare, cooking, and pig care. Men oversee political affairs and defend clan territory during conflict. Coffee cultivation is primarily men’s work, as is wage labor, while women dominate local markets, selling fresh produce and small goods.

Marriage creates vital social and economic bonds between the groom’s and bride’s kin groups, formalized through the exchange of bride-price — usually pigs and/or money— arranged by senior clan members. Men typically marry in their early twenties; women, between fifteen and eighteen. Postmarital residence is usually patrivirilocal (living in the husband’s family home or community). Polygyny remains practiced, though less common due to Christian influence, and is valued because multiple wives increase household productivity. Marriages are often unstable before the birth of children, though divorce can occur even years later.

Brothers jointly inherit their father’s land and crops, with distribution occurring as sons marry and the father ages. Other valuables are shared among relatives after death. The land of childless men is reassigned by senior members of the clan.

Chimbu Children and Initiations

Infants and young children have traditionally been cared for mainly by their mothers and older sisters. Formerly, boys around age six or seven left their mothers to live with their fathers in the men’s house. Today, about half of Chimbu children begin school at roughly the same age. Until adolescence, girls spend much of their time assisting their mothers with domestic and gardening tasks, while boys form play groups with age-mates from nearby households—bonds that often continue into adulthood. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The traditional male initiation ceremony, once central to Chimbu ritual life, is no longer practiced after being discouraged by missionaries. However, the large pig-killing festivals (bugia ingu) still occur, though with reduced emphasis on offerings to ancestral spirits.

In the past, male initiation took place during preparations for these festivals. Boys and young men were secluded at the ceremonial ground, where elders taught ritual knowledge, flute lore, and proper conduct. The rites, held every seven to ten years, included all uninitiated youths and involved bloodletting and painful ordeals marking their transition into manhood. Today, only the symbolic display of the sacred flutes remains part of the feast.

At first menstruation, girls were traditionally secluded and instructed in proper behavior, followed by a family feast celebrating their maturity. Some families still observe simplified forms of this rite.

Chimbu Kinship and Land

The Chimbu trace descent patrilineally, organizing themselves into “brother” groups that descend from a common male ancestor. The clan, typically numbering 600–800 members, is the usual unit of exogamy — marriage outside the clan. Clan names often combine the founder’s name with a suffix meaning “rope.” Each clan is subdivided into subclans of 50–250 people, which serve as the main units for organizing ceremonies such as marriages and funerals and for coordinating joint agricultural work. Within subclans, smaller “one blood” or men’s house groups consist of close patrilineal relatives. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Chimbu kinship terminology follows the Iroquois (bifurcate merging) pattern, distinguishing relatives by both generation and gender. A father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are addressed by the same terms used for “father” and “mother,” while a father’s sisters and mother’s brothers are called by distinct terms equivalent to “aunt” and “uncle.” The children of same-sex siblings — parallel cousins — are classified as siblings, while the children of opposite-sex siblings — cross cousins — are recognized as cousins and potential marriage partners.

Land is divided among several plots differing in soil and altitude. Inheritance usually passes jointly from father to sons, though claims may also arise through ties to more distant male relatives, in-laws, or affines from other clans. Rights to fallow land remain with the last user so long as they are defended. Despite high population density, outright landlessness is rare, as people can often gain access through kinship or marriage connections.

However, the growth of cash cropping — especially coffee — has created shortages of suitable land for commercial cultivation. While food gardens remain available to all, opportunities for earning cash have declined, prompting significant migration. In some highland areas, over 30 percent of Chimbus have moved to towns or to less crowded lowland regions in search of land and work.

Chimbu Villages, Food and Life

Unlike many eastern highland groups, the Chimbu traditionally lived in dispersed settlements rather than compact villages. Men lived in large communal houses built on ridges for defense, apart from women, girls, and young boys. Each married woman lived separately with her unmarried children and pigs in a house located near the family gardens. This arrangement allowed women to manage both crops and pigs — central to household wealth and social exchange. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Today, with declining tribal warfare, reduced gender segregation, and increasing economic activity, more men live with their families in houses near coffee gardens and roads. Typical Chimbu houses are oval or rectangular, with thatched roofs, dirt floors, and reed walls.

Sweet potatoes dominate the Chimbu diet, still making up about 75 percent of daily food intake in the 1990s. Over 130 varieties are cultivated in different microenvironments for varied uses. Pigs remain the most important form of wealth, used in ceremonial exchanges that sustain social relationships. Gifts of pork, vegetables, money, or purchased goods (such as beer) create obligations that must later be repaid to maintain prestige. The largest of these exchanges is the bugla ingu pig ceremony, when hundreds or even thousands of pigs are slaughtered, cooked, and distributed among kin and allies to mark major events such as marriages, compensations, or clan alliances.

Chimbu artistic expression centers on body decoration — shells, feathers, wigs, and face paint are worn during ceremonies. Oral traditions such as song, poetry, drama, and storytelling serve both entertainment and education. Musical instruments include bamboo flutes, drums, and Jew’s harps. Illness and sudden death are sometimes attributed to sorcery, witchcraft, or the violation of spiritual taboos. Traditional herbal remedies were limited, and most people now rely on government medical posts and hospitals for treatment.

Omo Bugamo (Skeleton Men)

The Omo Bugamo, also known as the Skeleton Men, are among the most visually striking tribes of Papua New Guinea’s Highlands. Their traditional body art — men painted head to toe in black and white clay to resemble human skeletons — has made them one of the most recognizable cultural groups in the country. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

According to local tradition, the origin of the Skeleton Men’s haunting appearance dates back roughly 200 years. A group of hunters once ventured deep into the mountains but never returned. When their prolonged absence alarmed the villagers, a band of warriors set out to find them. Their search led them into a remote cave, where they discovered the bones of the missing hunters scattered across the ground. As they investigated, they realized they were not alone—a monstrous spirit lurked within the darkness. Known as Omo Masalai, this creature was said to feed on human flesh and could take on any shape or form. Possessing a heightened sense of smell, the spirit was nearly impossible to escape.

To outwit it, the warriors devised a desperate plan. They covered their bodies in black and white clay, painting on skeletal patterns to blend in with the bones of their fallen kin. The disguise worked. Mistaking the warriors for spirits of the dead, Omo Masalai left them unharmed, allowing them to slip away under the cover of night. Since then, the men of Omo Bugamo have painted their bodies as skeletons to honor the courage of those warriors and their triumph over the mountain spirit.

A more pragmatic version of the tale suggests the skeleton body paint was originally used to intimidate rival tribes—invoking fear of ghosts and death, which are deeply powerful symbols across the Highlands. Today, the Skeleton Men reenact their legendary encounter during performances at cultural festivals. At events such as the Mount Hagen Festival and Paiyakuna Show, the men appear silently, painted in white bones, confronting a performer embodying Omo Masalai in a dramatic exorcism ritual. The moment they step forward, an expectant hush falls over the crowd—a testament to the enduring power of their story.

Skeleton Dances

The Chimbu y paint their bodies to resemble skeletons for ceremonial dances. In the past the dances were combined with tribal warfare to scare opponents into believing the dancers were not human. [Source: Google AI]

Traditionally, chimbu skeleton dancers painted themselves with white clay and ash. They aimed to create the impression that they were supernatural beings to give them a psychological advantage in battle. Some stories suggest the practice was also used to scare away ghosts and evil spirits, allowing the people to hunt, gather, and garden without fear.

Skeleton dances are now primarily performed for cultural events like the Mount Hagen Festival, where they serve to showcase and preserve the tribe's heritage and traditions. The "skeleton men" are major attraction at these festivals — favorites of audiences and photographers. The dances also have a deep spiritual significance, representing ancestral spirits and a connection to their worldview and the land.

Chimbu Agriculture and Economic Activity

Sweet potatoes are the staple crop of the Chimbu. They are grown in fenced, tilled gardens — often on slopes as steep as 45 degrees. These gardens are laid out in a grid of ditches forming mounds about 3 to 4 square meters, where vine cuttings are planted. Gardens are cultivated year-round, with planting timed according to food needs for exchanges and the feeding of pigs rather than seasonal changes. Other crops include sugarcane, greens, beans, bananas, taro, and pandanus nuts and fruits. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Pigs are the most important domesticated animals and represent a family’s main wealth. Once sacrificed to ancestral spirits, they are now ritually blessed before slaughter. Money has become increasingly central to ceremonial exchange. Most rural families earn cash from small coffee gardens, selling vegetables in local markets, or occasional wage labor. Traditional crafts in clothing and toolmaking have largely disappeared, replaced by store-bought goods. Before outside contact, men crafted tools, weapons, fences, and houses from wood, cane, bamboo, and bark, while women made fiber items for daily use.

Chimbu Social and Political Organization

Chimbu society is organized around patrilineal kin groups that combine into larger units resembling a segmentary lineage system. Loyalties are strongest within the smallest local groups that share residence areas and resources. The clan, the main exogamous unit, acts collectively in major ceremonies and controls a common territory. The largest indigenous sociopolitical unit is the tribe, numbering up to 5,000 people, which unites for defense during intertribal conflicts. Marriages between members of different clans and tribes form vital political and economic ties beyond the local level. [Source: Karl Rambo and Paula Brown, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Chimbu Province today is divided into six districts, each containing 18 rural and two urban local-level government (LLG) areas, headed by elected Presidents or Mayors and councillors. The province has several secondary schools, including Kondiu Rosary, Yauwe Moses, Kerowagi, Muaina, Gumine, Mt Wilhelm, and Kundiawa Lutheran Day Secondary School, as well as numerous high and primary schools.

While traditional tribes were once the largest political units, parliamentary democracy introduced in the late 1950s expanded political boundaries. However, the influence of local “big-men” — leaders who organize exchanges and mobilize electoral support — remains strong. Because many candidates compete within the same tribal group, elections are often won with less than 10 percent of the vote. Thus, modern politics has not significantly expanded the scale of traditional leadership.

Disputes are commonly resolved through mediation by influential men rather than violence, though the threat of conflict continues to shape behavior. Accusations of witchcraft, often directed at women who marry into patrilineal groups, reflect fears of divided loyalties. Warfare, once constant between tribes and occasionally within them, declined after colonial contact but resurged in the 1970s. Though competition over land is a frequent cause, fights are often triggered by disputes involving women, pigs, or unpaid debts.

Insect Hunters of Mindima

Mindima Village in Simbu Province is home to a remarkable group of skilled insect hunters — families who have developed a tradition that blends ingenuity, survival, and a deep respect for the natural world.These Insect Hunters employ a clever technique that uses smoke to capture a wide variety of insects. Believing that the smoke confuses and immobilizes their prey, they carefully manipulate its density and direction, demonstrating a fine-tuned understanding of both fire and the habits of local insects. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

Their methods reveal not just exceptional hunting ability but also an intimate knowledge of their environment. Each technique is tailored to a specific type of insect — from the swift capture of flying species to the delicate coaxing of those hidden in foliage. The hunters’ precision and adaptability highlight generations of observation and skill passed down through time.

Insects also play a meaningful role in family life. When parents and children venture into the forest, hunger often strikes during long hunts. In these moments, parents roast freshly caught insects over glowing embers, transforming necessity into nourishment — and the act of sharing food into a cherished family ritual that strengthens generational bonds.

The rainforest’s unpredictable weather adds yet another challenge. Sudden rains often drench leaves and wood, making it difficult to start a fire. When hunters cross paths under such conditions, they share fire from their burning embers, helping one another to keep the hunt alive. This exchange, practical as it is symbolic, embodies the Insect Hunters’ sense of unity, cooperation, and resilience.

Daribi

The Daribi people inhabit the volcanic plateaus of Mount Karimui and Mount Suaru and the limestone ridges west of Karimui, in southern Simbu (Chimbu) Province near the borders of the Gulf and Southern Highlands provinces. Most settlements lie between 900 and 1,050 meters above sea level, within tall midmontane rainforest drained by the Tua River, a major tributary of the Purari. According to the Joshua Project the Dadibi population stands at about 29,000, of which 99 percent are Christian. The population has grown from about 3,000–4,000 at the time of pacification (1961–62) to over 6,000 in the 1990s, largely due to malaria control. [Source: Roy Wagner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Also known as the Dadibi, Karimui, Mikaru and Elu, Daribi speak a single language of the Teberan family, related only to Polopa; together these form the Teberan-Pawaian super-stock. Most Pawaian speakers at Karimui are bilingual in Daribi. According to tradition, the Daribi migrated from Mount Ialibu in the Southern Highlands eastward along the Tua River, where they intermarried with Pawaian groups before moving onto the Karimui plateau. Later encounters and conflicts with Wiru peoples led to the Daribi’s consolidation in their present territory. European contact began in the 1930s, and pacification followed in the early 1960s with the establishment of an airstrip, patrol post, and Lutheran mission at Karimui.

Daribi have traditionally been swidden farmers, with sweet potatoes as the staple, supplemented by sago in low-lying areas, and bananas, pandanus, taro, maize, yams, sugarcane, and cassava. Pigs are the main exchange animal and symbol of wealth; chickens and a few cattle are also kept. Hunting of wild pigs and marsupials, along with foraging for mushrooms, eggs, and sago grubs, remains significant. Cardamom has replaced tobacco as the major cash crop. Traditional crafts include canoe- and bowl-making, bark cloth, bamboo flutes, and carved arrows. Tobacco, formerly the principal trade item, was exchanged for bird plumes, which were traded with Chimbu peoples for salt, axes, and shells. Daribi artistic expression centers on storytelling (namu pusabo) and lyric poetry, with flute and Jew’s harp music and incised designs on arrows. Traditional medicine combined herbal remedies, surgery by skilled practitioners, and shamanic curing.

Daribi Life, Culture, Family and Religion

Traditionally, extended or polygynous families lived in single-story longhouses divided into men’s and women’s quarters. In wartime, entire clans might occupy two-story longhouses (sigibe’) for defense, with men above and women below. Today, nucleated villages and hamlets with single-story longhouses arranged in rows are typical. Clans are patrilineal and exogamous, composed of sibling groups (zibi) and grouped into larger kin units descended from named male ancestors. Kinship combines Iroquois and Hawaiian features. Leadership is informal, centered on influential “big-men” (genuaibidi) who gain followers (hana) through generosity, marriages, and successful mediation. Social control traditionally relied on gossip, public opinion, and fear of sorcery. Warfare once involved ambushes and sieges between allied clans, but has been replaced by mediation and village courts.

Girls were traditionally betrothed from infancy to prestigious men; polygyny was common. Men typically married later, after accumulating bridewealth. Marriage was virilocal, and a woman’s kin retained rights to her and her children unless “head payments” were made. Divorce or widow remarriage often involved the simple transfer of a woman to another man within her clan. Inheritance followed the male line, while gardens passed to surviving spouses or partners.

Daribi belief centers on ghosts (izibidi) and local spirits inhabiting trees, ravines, or the earth. Illness and misfortune are often attributed to their displeasure. Spirit mediums (usually women) and shamans (sogoyezibidi), who are believed to have “died” and returned with spirit allies, serve as curers. The principal ritual, habu, recalls the ghost of someone who died unmourned; young men, temporarily “possessed,” hunt and later rejoin the community in a mortuary feast. The dead are thought to live together to the west, possibly in a lake.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025