Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

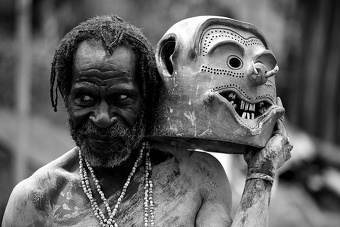

ASARO MUDMEN

The Asaro tribe, also known as the Holosa, live just outside the town of Goroka in the Asaro Valley in the Eastern Highlands. Asaro men — Asaro mudmen — smear their bodies with white clay and perform skits and dances wearing earthen masks impregnated with animal teeth. The practice of wearing these costumes, which are performed mainly in front of paying tourists and photographers, originated for a cultural show in 1957, and has subsequently become an important marker of identity for the Asaro tribe and has been copied in other parts of the highlands. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Asaro population is estimated to be 45,000 people. The majority of Holosa speak a language called Dano, as well as Tok Pisin, the lingua franca throughout Papua New Guinea. Their their unique ceremonial masks are called Holosas. The word Holosa means “spirit” or “ghost”. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The masks are fashioned from clay—traditionally sourced from the Asaro River, as this clay is said to resist cracking as it dries—and are decorated with items such as pig tusks and shells. Originally, their internal structure consisted of bamboo and bilum fibre, but by the 1970s, banana roots were used instead, allowing for more rounded forms. Later versions were made entirely of clay, which, while heavier and wearable only for short periods, were quicker to produce.

Across the Highlands, warriors often covered their bodies in charcoal to appear more intimidating or in clay and mud as an expression of grief. In Mount Hagen, for instance, men returning to avenge fallen comrades painted themselves with orange and yellow mourning clay. Many also believed that mud held magical properties that offered protection in battle. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Origin of the Asaro Mudmen

According to a popular legend, the Asaro people were once defeated in battle and sought refuge in the Asaro River. There, they encountered a mysterious figure who granted them the power to kill with their eyes. At dusk, they attempted to escape, but one man was captured. Emerging from the muddy riverbanks covered in mud, he was mistaken by the enemy for a spirit, prompting them to flee in terror—a reaction rooted in the widespread fear of spirits among Highland tribes. Because the Asaro believed the river mud to be poisonous, they later crafted masks from heated pebbles mixed with waterfall water.

Research conducted in September 1996 by Danish anthropologist Ton Otto of Aarhus University has traced the origins of the Mudmen tradition to the village of Komunivea in the Asaro Valley. According to Otto’s findings, the custom began in the late 19th century when a villager named Bukiro Pote travelled to the nearby Watabung area and observed a practice known as bakime—the use of white sap to obscure one’s features during attacks. Bukiro Pote adapted this concept into a form called girituwai, which involved moulding mud over a lightweight frame worn on the head, with holes cut for vision. These mud coverings served as a means of disguise for assassinations but were not considered formal attire for warfare. The practice was soon adopted by other members of the village. [Source: Wikipedia]

The tradition was reportedly revived in 1957 by Ruipo Okoroho, Bukiro Pote’s grandson, for the first Eastern Highlands Agricultural Show. Tasked with presenting a cultural practice from his community, Okoroho and the Komunivea villagers agreed to showcase girituwai rather than their customary ceremonial dress. It was likely during preparations for this event that the masks evolved from simple, functional disguises into more elaborate artistic creations, with performers painting their bodies white to match the masks. Drawing inspiration from the ancient practice of bakime — in which warriors disguised themselves in mud, clay, or tree sap before a raid — the villagers devised a haunting new version for the event. Around 200 masked Asaro marched into the show, terrifying onlookers and winning first prize. Their subsequent parade through Goroka town terrified locals, who believed they had seen ghosts. One rival tribe, the Ifi Yufa, even composed a song about the frightening “holosa,” meaning “ghosts” in the Asaro language. The Komunivea village and its leaders have since benefited greatly from tourism inspired by the Mudmen, and have at times defended their cultural ownership of the tradition through legal means.

According to a BBC feature titled Behind the Masks, one popular tale about the origins of the Mudmen custom tells of an Asaro man invited to a wedding where all guests wore traditional costumes. Having none of his own, he decided to improvise—covering his body in mud and fashioning a mask from clay and a bilum (a traditional woven bag). When he arrived at the celebration, his friends mistook him for a ghost and fled in terror. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Another Asaro legend offers a more dramatic origin. After losing their fertile lands in a series of fierce battles, the Asaro were forced to inhabit the less arable highlands of Papua New Guinea’s Eastern Highlands Province. Life was difficult, and after years of hardship, the warriors decided to reclaim their ancestral lands. Vastly outnumbered, they retreated to the banks of a muddy river, where their bodies became coated in pale, sunbaked clay. When their enemies discovered them, they believed these ghostly figures were the spirits of the warriors they had previously slain and fled in fear.

Realizing the power of this illusion, the Asaro decided to use it strategically. Believing the Asaro River water to be poisonous, they avoided coating their faces with mud and instead used sticks, stones, and natural materials to create crude masks. The eerie gray bodies and ghastly masks struck terror in their foes. Ironically, the peaceful Asaro earned a lasting reputation as fearsome warriors—though their greatest weapon was deception, not violence. As many Highland groups smeared mud to prepare for battle, the Asaro wore it to avoid battle. “If you can generate fear,” they reasoned, “you do not have to go to war.”

History of the Asaro Mudmen Masks

The masks were later called holosa—meaning “ghost” in a neighbouring language—a term that the Asaro people adopted. A dance was created to accompany the masks, imitating the jerky, unsteady movements of a spirit with broken bones, swatting away flies drawn to decaying flesh. Some scholars suggest that the girituwai concept may reflect a broader Highland tradition of using mud or other materials to conceal the body, whether for combat or mourning. The English name “Mudmen” appears to have been coined by visiting tourists who attended cultural fairs.

Over the years, the Mudmen’s masks have evolved. In the early 1970s, the traditional bamboo-and-bilum frame was replaced with smoothed banana roots. Because this process was laborious, clay masks became the standard by the late 1970s. Also over time, mask designs shifted from predominantly menacing expressions to friendlier ones, in response to tourist preferences.

Today, the Mudmen wear sun-dried clay masks with exaggerated features — arched brows, horns, pointed upturned ears, drooping tongues, extended eyebrows connecting to the ears, sideways-set mouths and pig bones through the nose. No two masks are alike; each reflects the creativity of its maker and the intention to evoke fear. The rest of the costume consists of sharp bamboo shards attached to the fingers, producing a clicking sound as they move. Leaves and grasses cover their genitals, while bows, arrows, and spears complete the ensemble. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Asaro Mask Making and Performance

The mask-making process begins with shaping an oval head form from coiled rings of clay, to which facial features are added. The rich, sticky clay for Asaro maks is collected from local creeks and brought to a master mask maker. The artisan inspects and purifies the clay, rolls it into balls, and shapes it into rings that are stacked and smoothed into an oval head form. Deep-set eye sockets are carved, ears and noses attached, and mouths are shaped—sometimes with gray tongues and pig’s teeth. Tattoo-like markings may also be impressed on the forehead and cheeks. Some masks feature tusks through the nose or tattoo-like engravings on the cheeks and forehead. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The mud used to create their costume is said to have magical properties and is believed to protect the wearer from harm. Once formed, the masks are sun-dried over several days, hardening into heavy helmet-like headdresses that can weigh 20–25 pounds and measure nearly two centimeters thick. The masks are very heavy.

Performed during major ceremonies, Asaro mudmen dances are distinguished by sudden, jerky movements and the exaggerated facial expressions of the mud masks. Dancers, covered in traditional grey clay and adorned with minimal attire, move in haunting unison, creating a mesmerizing spectacle that evokes both fear and fascination among onlookers. Performers paint their bodies white (excluding the masked head) and wear long bamboo extensions on their fingers. Like their attire, the Mudmen’s performance is uniquely haunting. Unlike most Highland groups, they do not sing, chant, or play instruments. Instead, they perform in total silence—moving slowly, miming stories in a ghostly pantomime. Their movements suggest brittle bones and decaying flesh as they stalk imaginary prey, sometimes swatting at invisible flies that feed on their “rotting” bodies.

One of the most celebrated performances is the Moko Moko Dance of Victory, a spirited celebration performed by Asaro warriors upon their triumphant return from battle. The dance is accompanied by an atmosphere of jubilation and festivity, often marked by revelry, music, and communal feasting. During these celebrations, indulgence in alcohol and sexual expression forms part of the ritualized joy of victory. The Moko Moko Dance is more than a performance — it is a ritual affirmation of triumph and unity. Warriors, adorned in vibrant bilas (traditional ornaments), elaborate feathered headdresses, and shell decorations, move in powerful rhythmic patterns that embody strength, pride, and the spirit of their ancestors. Each movement and gesture tells a story of courage, struggle, and victory. The symbolism of the dance is deeply rooted in Asaro heritage. The bilas — made from shells, feathers, leaves, and other sacred elements — reflects the warriors’ connection to their lineage and the natural world. Through their synchronized movements and chants, the dancers reenact past battles, celebrate resilience, and honor the collective spirit of their people. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

Asaro Society, Food Life and Religion

The Asaro live in small communities near the Asaro River, close to Goroka, from which their name derives. Many still live in traditional ways, and their dialect, Dano—part of the Kainantu-Goroka language family—is spoken only in a few areas of Papua New Guinea. Traditionally, the groom’s family pays a bride-price to the bride’s family, often in the form of livestock, crops, cash, or gifts. After marriage, the bride takes on the responsibility of caring not only for her husband but also for his extended family. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The Asaro are expert cultivators of sweet potatoes, their staple crop. Their deep understanding of soil, weather, and crop rotation enables them to harvest abundantly year after year. The Asaro hold a profound respect for the land and believe their ancestors’ spirits dwell among them and in their gardens.Traditional mumu ovens are a cornerstone of Asaro cooking. A pit is lined with wood, stones, and banana leaves. As the wood burns, the heated stones fall to the bottom, and food—corn, yams, greens, and meat wrapped in leaves or bamboo tubes—is placed atop to cook. Unlike the Kalam people, who preheat stones separately, the Asaro burn wood directly in the pit.

Most Asaro today are Protestants, but their faith blends Christian beliefs with traditional spiritualism. They believe supernatural beings inhabit rivers, forests, and caves, and that offerings can secure protection from misfortune. The Asaro recognize three main types of spirits: 1) Dama – spiritual beings; 2) Dimini, ancestral spirits, and 3) Tomia, spirits that inhabit objects or talismans.

Puri Puri—meaning “black magic” in the Motu language—is a night ritual involving sorcery. Practitioners known as Puri Puri Men chew special rainforest roots, leaves, and betel nut, then blow the mixture as a mist to cast spells of illness, misfortune, or even death. There are three levels of Puri Puri practice: 1) Common – general herbal knowledge shared among villagers; 2) Specialized – performed by trained healers or diviners who predict weather or cure illness; and 3) Secret – a highly guarded level practiced only by elders, addressing advanced healing or social disputes. These specialists can both cast and neutralize spells.

Burning Heads of Gimmesave

The Burning Heads of Gimmesave is a remarkable tradition deeply connected to the legendary Mudmen of Asaro. Long before coffee cultivation reached Papua New Guinea, the fertile Asaro Valley thrived with vast banana plantations — the lifeblood of the Gimmesave people. These crops symbolized both nourishment and abundance, yet their prosperity was constantly threatened by swarms of birds and giant bats that feasted on the ripening fruit.

To defend their harvest, the ancestors of Gimmesave devised a bold and imaginative solution. They covered their bodies with white mud and streaks of black clay to resemble the plumage of the very creatures they sought to repel. From banana stumps and moss, they crafted large headpieces, which they then set aflame. As night descended, the flickering glow of their burning headgear cast eerie shadows across the plantations, terrifying the birds and bats into flight.

Over generations, this ingenious act of survival evolved into a symbol of identity and resilience. The Burning Heads of Gimmesave, once a practical method of crop protection, is now performed as a striking cultural spectacle — a vivid celebration of ancestral creativity and the enduring spirit of the Gimmesave people. Today, its fiery display not only captivates visitors but also honors the legacy of those who turned necessity into lasting tradition.

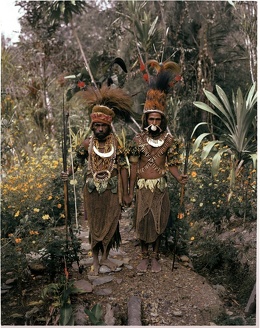

Mount Hagen Area Tribes

The O Wara are an enigmatic tribe that lives deep in the rugged mountains near the Mount Hagen region, with their settlements stretching almost to the coast. Their name comes from two words: “Roun” meaning “circle” and “Wara” meaning “water.” Renowned for their striking appearance, the O Wara adorn themselves with black paint and foliage from local plants in preparation for warfare. These decorations are not merely ornamental — the paint is believed to provide spiritual protection, while the plants and leaves often possess medicinal properties used to treat wounds sustained in battle. Some O Wara villages are nestled along mountainsides. The tribe’s mountaintop settlements were deliberately chosen for strategic defense, offering protection from rival groups. Despite the pressures of modernization, the O Wara have maintained their independence and cultural identity. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

The Black Mamas and the Jiwaka people are among the many vibrant groups that perform at the Mt. Hagen Cultural Show. The women known as Black Mamas are distinguished by their striking attire. Their skirts are made from cordyline leaves, folded in an accordion style and secured with a bilum belt. Some women wear a bandeau pelt crafted from the fur of the cuscus, adding a touch of natural elegance to their costume. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The name “Jiwaka” itself is a portmanteau, formed from the first two letters of Jimi, Wahgi, and Kambia—three key regions that define the province’s geography. The Jimi and Kambia mountain ranges rise at the northern and southern ends of the fertile Wahgi Valley, the cultural heartland of the Jiwaka people. In the past, male initiation ceremonies were common but have become rare today due to the influence of modernity and Christianity.

The Jiwaka maintain several rich ceremonial traditions that reflect both social unity and community renewal: 1) Konk Numb – A joyous courting ceremony where young men and women, adorned in traditional ornaments and vibrant face paints, gather to sing, dance, and celebrate. The term Kong Gar, meaning “pig’s house,” is often used interchangeably, referring to large ceremonial feasts marked by the slaughtering of many pigs. 2) Ana Kolma – A lavish reconciliation ceremony that signifies new beginnings not only between couples but also between tribes. Similar to the tee ceremony of the Enga, Ana Kolma resolves conflicts and strengthens alliances through the exchange of gifts and pledges of peace. 3) Kunda Kumba – A solemn ritual conducted after a death—whether accidental or intentional—or after the destruction of property. It serves to heal rifts and restore social balance.

Before marriage, the groom’s family must pay a bride price, traditionally involving pigs and kina shells, both symbols of wealth and prestige. The payment compensates the bride’s family for her departure and solidifies social bonds between clans. Today, cash is often added to the exchange, and the negotiation process remains an essential part of the marriage itself, reflecting the perceived value and status of the bride.

The people of Western Highlands and Jiwaka Provinces are renowned for their spectacular headdresses and bilas (ceremonial adornment). Their elaborate decorations feature huge, brightly colored feathers, kina shells, pig tusks, and woven grasses. Faces are painted in vivid, bold patterns using natural pigments mixed with plant oils, pig fat, clay, and mud—transforming each dancer into a living canvas of cultural identity. Men wear bark belts with string aprons at the front and tanket leaf coverings at the back. Many also take pride in their beards, sometimes painting them to match their face colors.

Huli

Huli people are a highland tribe famous for their elaborate headdresses and face paint, and are one of the largest cultural groups in the highlands. They reside in Hela Province of Papua New Guinea and have an annual gathering in which they dress up in bright colors. "They preen, strut, shimmy, and shake their feathered costumes, mimicking the local birds of paradise." They are one of the largest cultural groups in Papua New Guinea and the largest ethnic group in the Highlands, numbering over 250,000 people (based on the population of Hela being 249,449 at the time of the 2011 national census). The Huli trace their ancestry to a legendary forefather named Hela, a masterful farmer who had four sons and one daughter—Opena, Huli, Duna, Tuguba, and Hewa. Each of his children is believed to have founded the neighboring tribes that now inhabit the Highlands, and Hela is honored as the ancestral guardian of the land’s fertility.

The Huli inhabit the Tari Valley in the lush and fertile Tagari River basin in the Hela Province (formerly part of the Southern Highlands). They live, about four hours from Mendi on the slopes of the surrounding mountain ranges at an altitude of about 1,600 meters above sea level. The climate there is tropical but cool and very rainy. The landscape consists of patches of primary forests, kunai grasslands, scrub brush, reed-covered marshes, and mounded gardens. Rivers, small streams, and man-made ditches traverse this landscape and serve as drainage canals, boundary markers, walking paths, and defensive fortifications.

The Huli primarily speak Huli and Tok Pisin. Many also speak some of the surrounding languages, and some speak English. The Huli language is a Trans-New Guinea languageknown for its unique pentadecimal (base-15) numeral system. Historically, the Huli were known as fierce warriors, with tribal wars fought over land, pigs, and women. While the Huli people have preserved many aspects of their traditional culture, modern changes and development projects, such as mining, have started to impact their way of life. However, they continue to uphold their traditions, and many Huli participate in regional festivals called "sing-sings" to proudly showcase their culture.

The Huli are keenly aware of their history and folklore and appear to have lived in their region for many thousands of years as evidenced by their knowledge of family genealogy and traditions and lengthy oral histories relating to individuals and their clans. The Huli were not known to Europeans until 1934 when Australian gold prospectors Jack Hide and Peter O’Malley crossed the Papuan Plateau and at least fifty of them were killed by the Fox brothers — two adventurers looking for gold. Over the following decades, new Huli clans continued to be encountered, with the last isolated groups contacted in the early 1960s. Unlike many other Highland peoples, the Huli have not relinquished much of their cultural expression to the new, innovative ways of the colonizers and outsiders who settled among them in 1951.

Huli Ceremonial Clothes and Adornment

Huli men wear a red woven belt supporting a long apron and a smaller front covering. Their backs are draped with red and green cordyline leaves, chosen for their sheen and color, and cinched tightly with a wide hago belt made from cane fiber. This belt posture enhances their upright stance and chest prominence. Accessories include kina shell breastplates, pig tusk and hornbill necklaces, cowrie shells, armbands, and leg bands. The most striking element, however, is the ceremonial wig, elaborately styled and symbolizing male maturity and spiritual power. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

During ceremonies, Huli men paint their faces with vibrant red and yellow clay, which they believe is sacred. They also use yellow ocher clay (ambua), red ocher, and other natural pigments to create symbolic patterns that signify their identity, strength, and connection to the land. Ceremonial wigs (manda hare) are dyed red or black and decorated with feathers, flowers, and ochre paints (See Wigmen Below). Faces are covered in yellow ambua, highlighted with red, white, and black pigments. Bodies glisten with pig fat or tree oil, symbolizing vitality and beauty. Everyday wigs (manda tene) are simpler, used when not performing or engaging in rituals.

Huli women wear long grass skirts—sometimes dyed black—and often pair them with European-style smocks or go bare-chested, depending on age and custom. They adorn themselves with beaded necklaces, kina shells, and flowers, but unlike men, do not wear wigs or leg bands. Both sexes carry a bilum (string bag). Women often use it to carry produce—or even infants—on their backs with the strap across their forehead. Men wear it across the chest, storing tobacco, red paint, mirrors, and other essentials.

Huli Wigmen

The Huli Wigmen are among the most visually striking and culturally distinctive peoples of Papua New Guinea’s Highlands. Renowned for their elaborate wigs made of human hair and their bold face paint, the Huli wigmen originate from Magarima, Koroba-Kopiago, and Tari-Pori districts in Hela Province. They project an aura of strength, beauty and disciplined masculinity—an impression heightened by their commanding physical presence and warrior bearing. Their powerful presence, enhanced by vibrant face paint and ornate headdresses, commands attention wherever they appear—especially during cultural festivals like the Paikayuna Show. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Huli "wigmen," grow and weave their own hair into large, ceremonial wigs adorned with flowers, fur, with feathers from cassowaries, cockatoos, and the iridescent bird of paradise and other decorations and are symbols of status, skill, and pride. Rituals and ceremonies are a vital part of Huli life. Young men go through a period of training called "Wig School" to learn how to create their wigs and prepare for adulthood. They also perform ceremonial dances and maintain a strong connection to ancestral spirits and nature through strict rituals.

At around 12 or 13, a boy begins his transformation into a man through a period of seclusion and ritual discipline—traditionally under the Haroli bachelor cult, later replaced by “wig schools” or "bachelor schools", where they are completely secluded from women for 18 months to three years. During this time, they learn to purify their bodies, and ritually grow and cultivate their own hair under the guidance of a spiritual leader. They wash their hair daily with dew, recite spells, and sleep on wooden headrests to protect their growing hair. After about 18 months to a couple of years, the hair is harvested to craft impressive ceremonial wigs adorned with feathers and other decorations. According to one description: "He uses leafy twigs to drip sanctified water on his hair as it grows into a mushroom shape around bamboo supports. Soon it will be sheared off in one piece to make a wig he'll wear the rest off his life." Men often grow several wigs before marriage, and wigs can also be sold to others for significant sums.

The strange-looking wig-hats of Huli men resemble mushroom caps or pirate's hats except they are covered by fur and have feather protruding from them. And, Huli wigs aren't just for show. The color, length, and style of each wig says something important about the wearer. Hands never touch the hair of a Huli bachelor. The traditional Haroli bachelor cult has all but disappeared, replaced by modern schooling and Christian influences. Yet many Huli elders express a deep desire to preserve their ancient teachings and reinstate the cultural institutions that once defined manhood and identity.

Huli Society and Sex

The Huli are agriculturalists and pig farmers, with sweet potatoes being their staple food and pigs being a main source of wealth used for bride price and other payments. The Huli have no formal chiefs. Leadership is earned through valor in warfare, wisdom in mediation, and wealth in pigs and shells. Respected men live ascetic lives, avoiding women and maintaining high moral standing—qualities believed necessary for authority and respect. Huli men and women have traditionally lived in separate houses. Women typically care for children, tend gardens, and raise pigs. Men are responsible for building houses and hunting. Boys stay with their mothers until about age seven, then move to their fathers’ or a communal boys’ house. From then on, they are trained in agriculture, construction, hunting, and the spiritual practices that define Huli masculinity.

Huli society is centered around hereditary clans (hamigini) and subclans (hamigini emene), with a strong emphasis on oral history and ancestral stories. Clans and subclans have traditionally managed their own affairs, including making peace or war. Clan membership is based on lineage, and each clan has residential rights to a specific territory. Huli spirituality is deeply connected to nature and ancestral spirits. They believe in a spiritual life force called Amb Koramane, which is passed down from ancestors to their descendants and must be maintained through rituals.

Warfare was once the central organizing principle of Huli society. Boys aspired to become warriors (wayali), learning archery, weapon-making, and combat sorcery. Revenge—through violence, sorcery, or compensation—was considered a moral duty to restore balance. Weapons included axes, bows, six types of arrows, bark shields, and fighting picks. The Huli also believed that humans are composed of three entities—body (dongone), mind (mini), and spirit (dinini)—and that destroying one could destroy the person entirely. Even today, the Huli retain a fierce sense of justice and retribution, though large-scale warfare has largely been replaced by police mediation and state intervention.

Historically, conflicts often arose from revenge killings, pig theft, or unpaid debts. While formal compensation could settle disputes, vengeance remained the preferred resolution. Wars were typically halted through mutual agreement or external mediation, though today, government forces sometimes enforce peace through intimidation—burning gardens or seizing pigs to end feuds.The Huli proverb could be summarized as: “Vengeance restores balance, but peace restores life.”

According to the Archive of Sexuality: Among the Huli young males leave the maternal house after initiation at age 7 or 8 to join their fathers, to avoid (sexual) contact with women. Men of 25 are married to 15-year-olds, whose virgin vagina has to be oiled in order to prevent damage to his penis. In 1968 R. M. Glasse wrote: “Young men begin to think of marrying when signs of their physical maturity appear; these include the quality and “firmness “ of the skin, abundant body hair and growth of a heavy beard. When these signs are evident, the men resign from the bachelor societies, don the crescent-shaped wig and evince an interest in attractive girls. They do not attend courting parties; these are the prerogative of married men”. The men are hesitant, for they are warned about the dangers of (menstruating women. “before marriage, the lovers are unlikely to have sexual intercourse. A single man fears coitus without the magical preparation that is available only to married men”. [Source: Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Huli Life

The Tari landscape is a patchwork of gardens cultivated by both men and women. They grow sweet potatoes, taro, pumpkin, beans, corn, cabbage, tobacco, and other greens. Around their homes, banana, pineapple, papaya, and bamboo trees thrive—the bamboo serving as both food and raw material for mats, musical instruments, and tools. Sweet potato is the Huli’s main staple, eaten daily and considered indispensable to a proper meal. Rice and fish, introduced by colonizers, are viewed as supplementary foods rather than replacements for their traditional diet. Both men and women raise pigs, which are a primary source of protein and also the cornerstone of social and economic exchange. Pigs are used as bride-price, ritual offerings, and currency in major transactions and compensation payments. A typical bride-price may involve 19 to 26 pigs, depending on the bride’s perceived value or skills. Though modern money is in circulation, pigs remain the preferred and most respected form of wealth. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Traditional Huli houses are built from wood, kunai grass, and woven bamboo or reed walls. They are small—roughly 10 feet wide and 20 feet long—with low ceilings and no windows. The front area serves as the living and cooking space, where a small fire burns continuously; the back section is for sleeping. Smoke-blackened rafters and soot-covered interiors are typical, with a small three-foot-high door serving as the only entrance. Alongside the main house stands an open, thatched-roof shelter used as a cookhouse and social space, where villagers gather to prepare food, talk, and rest.

Men and women live in separate dwellings. As in many Highland societies, Huli men believe women’s bodies—particularly menstrual blood—can sap a man’s strength, pollute his skin, and even hinder the growth of his wig. This belief in “female contamination” shapes gender relations and reinforces strict segregation. Rather than centralized villages, the Huli live in dispersed homesteads, organized into patrilineal clan units called hame ignini (“children of brothers”).

Kalam

The Kalam reside in the mountains in the Simbai region of Madang province and are known for their spectacular headdresses can reach a meter in height and are made from thousands of iridescent green beetle heads, bird of paradise feathers and furs. They are also known for their unique culture and strong connection to the forest.The Kalam have deep traditional knowledge, particularly concerning the diverse flora and fauna of their environment. [Source: Google AI; Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The Simbai region is comprised of a remote valley nestled in the heart of the Bismarck Mountain Range in Madang and Jiwaka Provinces. The area borders both the Western Highlands and Sepik provinces. Though Simbai sits high in the mountains, it is considered part of the Wagol River basin, technically making it a “coastal” area of Madang. The people of Simbai, particularly the Kalam, are often noted for their shorter stature and their warmth toward outsiders. Simbai is among Papua New Guinea’s most isolated regions, accessible only by small charter aircraft or by a demanding trek through rugged terrain. This remoteness has helped preserve Kalam culture, allowing it to flourish largely untouched by outside influence.

Due to their isolation, many Kalam people maintain a traditional lifestyle, living in huts built from local materials like pandanus leaves. The Kalam possess extensive and precise knowledge of the natural world, including a large vocabulary for local plants and birds, which they use for various purposes from medicine to hunting. The Kalam hold festivals, which are significant cultural events involving traditional dances and celebrations, and are sometimes open to adventurous visitors.

Kalam Life and Society

The Kalam live in scattered villages and are described as having strong, friendly relationships within the community, sometimes referred to as a large family. Their economy is based on traditional subsistence farming and hunting. The word Kalam is believed to originate from the Sanskrit kula, meaning “society” or “family”—a fitting reflection of their communal way of life. Villages are composed of wooden huts framed with rainforest materials. Walls are built from karuka (pandanus) leaves and mud serves as a natural cement. The roofs, woven from thatch, provide excellent insulation and protection from the rain. Homes are scattered in traditional patterns throughout the forest, blending harmoniously with the landscape. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The Kalam follow a patrilineal system in which descent and inheritance pass through the male line. Men are regarded as heads of households, while women are expected to be submissive to their husbands. Male children are especially valued for continuing the family lineage, and newborns are named after their ancestors. Justice among the Kalam is direct and severe. Those who commit serious offenses may face death or being burned alive—reflecting a traditional belief that strong deterrence maintains peace and order in their secluded world. When a person dies, a “house cry” is held. Women sit with the bereaved family, wailing and covering their faces with dirt as a sign of mourning and solidarity.

Kalam male headdress soul-o-travels

Daily life is defined by a clear division of labor: women tend the gardens, raise children, and manage domestic tasks, while men hunt, build houses, cultivate land, and safeguard the village. The Kalam diet is plant-rich, featuring staples like sago, sweet potato, taro, cassava, leafy greens, and tropical fruits, supplemented by wild pigs hunted in the rainforest.

Historically, marriages were arranged, but today, many unions begin during initiation festivities. Men often choose their partners, while women’s choices are still limited by family arrangements. If a woman refuses an arranged marriage, she may flee to avoid the union. The average marriage age is around 25. Women are typically quiet in the presence of men, a reflection of Simbai’s deeply patriarchal culture. When interviewed separately, they spoke candidly about their daily lives, childbirth, and social expectations. Unmarried women are expected to obey their fathers or male guardians. During menstruation, they isolate themselves near rivers for frequent bathing, as feminine hygiene products are unavailable. Pregnant women give birth in separate huts built by their husbands, aided by experienced mothers rather than trained midwives. Herbal remedies and spring water are used to ease labor.

After childbirth, mothers follow strict taboos: they avoid men, meat, sweet foods, and even handling food with their hands. Their diet consists mainly of bananas and hot water until recovery. Due to these conditions, maternal deaths are not uncommon. When a mother dies, her child is raised collectively by the village—an embodiment of the Kalam’s strong sense of kinship. Widows and unmarried women are cared for by nieces, nephews, or extended family, ensuring that no one is left alone.

Kalam Celebrations and Adornment

One of the Kalam’s most important culinary traditions is the mumu—an earth oven used to prepare food during feasts, weddings, births, or reconciliation ceremonies. Hot stones are layered in a pit, covered with banana leaves, and stacked alternately with food and more leaves. The heat and steam cook the food slowly, infusing it with smoky flavor. A whole pig is often the centerpiece of the feast, with every part consumed—a tradition the Kalam describe as eating “from the rooter to the tooter.”

Kalam men are famous for their spectacular headdresses, which can exceed a meter in height. The crowns are made from the shimmering green wings of thousands of beetles (Torynorrhina flammea chicheryi), known locally as mimor. These iridescent insects emerge during the fruiting season and are gathered in great numbers for decoration. The headdresses are further adorned with cuscus fur, flowers, and feathers from birds of paradise, parrots, and cockatoos.

Men also wear bilas—traditional ornaments including necklaces made of yellow orchid stems, kina shells, hornbill beaks (kokomo), and cuscus fur. Their attire often includes loincloths or leaf coverings (tanket or arsegras), pig-fat body oil, and feathers threaded through pierced septums.

As in many Highland cultures, Kalam boys undergo an initiation into manhood between the ages of 10 and 17. During this period, they live in a hausboi (men’s house), where elders teach them cultural traditions, responsibilities, and tribal laws. The initiation includes the sutim nus ceremony—piercing the septum with bamboo or cassowary bone—and the slaughter of numerous pigs. If enough pigs are not available, the ceremony is delayed until the required number is gathered. Large-scale initiations involving over 100 pigs occur every three to six years, attracting surrounding communities in a grand celebration similar to that of the Chimbu people.

Omo Bugamo (Skeleton Men)

The Omo Bugamo, also known as the Skeleton Men, are among the most visually striking tribes of Papua New Guinea’s Highlands. Their traditional body art — men painted head to toe in black and white clay to resemble human skeletons — has made them one of the most recognizable cultural groups in the country. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

According to local tradition, the origin of the Skeleton Men’s haunting appearance dates back roughly 200 years. A group of hunters once ventured deep into the mountains but never returned. When their prolonged absence alarmed the villagers, a band of warriors set out to find them. Their search led them into a remote cave, where they discovered the bones of the missing hunters scattered across the ground. As they investigated, they realized they were not alone—a monstrous spirit lurked within the darkness. Known as Omo Masalai, this creature was said to feed on human flesh and could take on any shape or form. Possessing a heightened sense of smell, the spirit was nearly impossible to escape.

To outwit it, the warriors devised a desperate plan. They covered their bodies in black and white clay, painting on skeletal patterns to blend in with the bones of their fallen kin. The disguise worked. Mistaking the warriors for spirits of the dead, Omo Masalai left them unharmed, allowing them to slip away under the cover of night. Since then, the men of Omo Bugamo have painted their bodies as skeletons to honor the courage of those warriors and their triumph over the mountain spirit.

A more pragmatic version of the tale suggests the skeleton body paint was originally used to intimidate rival tribes—invoking fear of ghosts and death, which are deeply powerful symbols across the Highlands. Today, the Skeleton Men reenact their legendary encounter during performances at cultural festivals. At events such as the Mount Hagen Festival and Paiyakuna Show, the men appear silently, painted in white bones, confronting a performer embodying Omo Masalai in a dramatic exorcism ritual. The moment they step forward, an expectant hush falls over the crowd—a testament to the enduring power of their story.

See Separate Article: CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025