Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

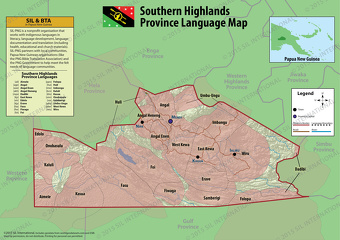

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS PROVINCE

Mendi woman in Malcolm Kirk's Door of Perception

Southern Highlands Province is almost in the middle of Papua New Guinea. It covers 15,089 square kilometers (5,826 square miles) and has a population of 972,306 according to the 2021 census. The population density is 64.5 people per square kilometers (167 people per square mile). The town of Mendi is the provincial capital. There are five districts: 1) Mendi-Munihu District; 2) Imbonggu District; 3) Kagua-Erave District; 4) Ialibu-Pangia District and 5) Nipa-Kutubu District. In 2012, The districts of Tari-Pori, Komo-Magarima, and Koroba-Kopiago split from the Southern Highlands Province to form the Hela Province. [Source: Wikipedia, Google AI; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Southern Highlands province is characterized by lush, high valleys nestled between towering limestone peaks. The mountainous landscape, including several significant peaks. Situated on the border of the Southern Highlands and Western Highlands provinces, 4,367-meter (14,327-foot) -high Mount Giluwe is the second-highest mountain in Papua New Guinea and the fifth highest in New Guinea. Fertile, enclosed valleys and upland basins are situated at elevations typically above 1,490 meters (4,900 feet). These areas are often have rich, volcanic-ash soils as result of past eruptions. The Kikori, Erave, and Strickland rivers whose headwaters flow through the region. Lake Kutubu, near the capital of Mendi, is the second-largest lake in the country. It is known for its high biodiversity and endemic fish species.The southern part of the province consists of lowlands, including the area around Lake Kutubu and the volcanic peaks of Mount Bosavi.

The central cordillera in the Southern Highlands is a complex system of ranges and broad upland valleys with forest, wild cane, and grasslands. There are many limestone escarpments as well as strike ridges composed of sedimentary rocks. The Kagua (1,500 meters, 4,921 feet) and Erave (1,300 meters, 4,265 feet) areas have extensive plateaus. The average yearly rainfall in the Kagua area is 310 centimeters (122 inches) and the temperature is 17-26° C (63-79̊ F) during the day and 9-17° C (49-63̊ F) at night. There is no marked wet-dry season, but June-August and December are usually the driest months.

The Southern Highlands province is bordered by Enga, Western Highlands, Gulf, Simbu, Western and newly-created Hela provinces. The town of Mendi is three hours from Mt. Hagen, the home of the famous Highland tribal show. Mendi is situated in a long valley surrounded by beautiful limestone peaks. South of Mendi is Lake Kutubu. As well as having some of the most beautiful scenery in the the Highlands there are many birds of paradise and amazing butterflies here, not to mention friendly tribespeople who still live as they have for centuries. Four hours from Mendi is Tari and the scenic Tari Basin. This area is home of the Huli wigmen, who are famous for their wild, crazy and colorful head dresses.

The Southern Highlands Province, especially around Lake Kutubu, is rich in oil and gas. It was at the centre of controversial plans to construct a gas pipeline to pump natural gas to Queensland in north Australia. The project would have resulted in much needed revenue for Papua New Guinea, but was scrapped due to fears of instability in the region. In August 2006, the government of Papua New Guinea declared a state of emergency in the country's Southern Highlands region. According to Prime Minister Sir Michael Somare, troops were deployed to restore 'law, order and good governance' in the region, following accusations of corruption, theft and misuse of government buildings at the hands of the regional government. During the 2022 provincial election, fighting broke out between supporters of sitting Governor William Powi and those of various regional candidates.

The region is divided into census divisions, with each parish electing a councillor to represent its people on the Local Government Council. The council collects taxes, maintains roads, schools, health centers, and aid posts, and promotes agricultural development. Representatives to provincial and national governments are elected according to population distribution.

Southern Highlands Ethnic Groups

The Southern Highlands of Papua New Guinea is home to numerous ethnic groups — over eight major groups and 18 to 24 distinct tribes — including the Huli, famous for their elaborate wigs adorned with bird feathers, and the Mendi, Wola, Wiru, and Duna people. The varied and rugged geography of the Southern Highlands Province has historically isolated many communities, contributing to the province's significant ethnic and linguistic diversity, with some tribes speaking languages that are distinct from their neighbors just one valley away. [Source: Wikipedia, Google AI; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Southern Highlands Province is divided into thre distinct geographic cultural regions: 1) The West, which includes the districts of Nipa, Mendi, Lai Valley, Imbogu (lower Mendi), Hela District of Magarima, Kutubu and part of Kendep (Enga Province) and is primarily home to speakers of dialects of the Anggal Heneng language; 2) The East, which includes districts like Kagua, Ialibu, Pangia and Erave, where languages such as Imbongu, Kewa, and Wiru are spoken; and 3) The Lowlands, which stretch across the southern part of the Southern Highlands province from the volcanic peaks of Mount Bosavi to the oilfields of Lake Kutubu, and includes the language groups of Biami, Foe, and Fasu.

In some parts of the Southern Highlands there is often no clear link between a person's language and their cultural identity — meaning there are people who have the same culture but speak very different languages and people who speak the same language can have very different cultures. Some tribes have connections to coastal populations and are a mix of both highlands and coastal descent. Others have territories that extending into neighboring provinces like the Hela, Enga, and Western Highlands. The Kutubu Bosavi are part of the Huli tribes but coastal. They speak Hela and the Foe Faso languages. The Erave Samberigi people also a coastal people. They speak their own language, Poroma. The people surrounding Mt Giluwe and Ialibu speak the Umbu-Ungu dialect while Pangia and Kagua people speak their two different languages. The Imboungu and some Ialibu people speak Kewabi languages.

The largest groups in the Southern Highland are: 1) the Huli, who also live in the Hela province and known for their elaborate wigs and ceremonial dress; 2) the Mendi, who speak a dialect of "Nongo-Naiko" language along withthe Poroma, Nipa, and Plato people; 3) the Wola, who live northeast of Lake Kutubu and speak a variety of the Mendi language; 4) the Wiru, who speaks the Wiru language and engage in rituals involving the production of timbuwarra from rattan; 5) the Duna, who reside in mountainous regions and have a traditional culture that includes the strict separation of males and females in raising and training children.

Mendi

Southern Highlands Province topographic map Dreamtime

The term "Mendi" refers to the people of the Mendi valley of the Southern Highlands. Also known as Angal, Anganen, Nembi and Wola, they are known for their elaborate gift exchanges and unique kinship terminology and have traditionally been subsistence farmers and raised pigs. In precolonial times, Mendi had no collective name for themselves. They still speak a variety of languages and dialects, and clans have active, long-standing relationships with peoples living elsewhere such as in Ialibu, Tambul, Kandep, the Lai Valley, and Kagua. [Source: Rena Lederman, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Mendi Valley is about 40 kilometers (25 miles) long and V-shaped. Located in the Mendi Subprovince of the Southern Highlands Province, Papua New Guinea, it is flanked to the east by Mount Giluwe and to the west by limestone ridges separating it from the Lai Valley, Most Mendi live north of Mendi town (the provincial government center, altitude about 1,620 meters above sea level). The topography of the valley is fairly rugged: gardens are planted up to about 2,400 meters above sea level. There is a large boggy area in the far northeast around Lake Egari. The valley receives about 280 centimeters of rain per year with only a slight wet/dry seasonal contrast. Approximate average daily temperature range from 7° to 24° C, with high-altitude areas regularly experiencing mild to severe crop-damaging frosts. ~

Approximately 58,000 people live in the Mendi Valley and surrounding areas. The 2021 census counted 56,108 people in the town of Mendi and over 40,000 people in Upper Mendi Rural LLG.Based on patrol reports dated 1959-1960 and 1961, anthropologists estimate the Mendi population of the late 1950s to be about 24,000. At the time of the 1976 government census, some 28,500 people lived in the Mendi Valley. Population density is moderate by highlands standards, and Mendi have enough land.

History: Under Australian administration, Mendi became the headquarters for the Southern Highlands District in 1950–1951. Despite its administrative role, the area remained among the least economically developed parts of Papua New Guinea. During the colonial period, from the 1950s until independence in 1975, the province’s affairs were largely shaped by government officials and Christian missionaries. After independence, a major World Bank–funded integrated rural development project was launched, and more recently, the discovery of mineral resources has begun to reshape the region’s economic prospects. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Mendi people Tribes of Papua New Guinea

Language: Mendi call their language "Angal Heneng," which means "true talk" or "normal speech." Dialects or closely related variants of the language are spoken in the Lai Valley and by Wola people living in the Was (Wage) to the west, as well as by people living in the Nembi to the southwest and south, where Angal Heneng and Kewa intersect in the speech of the Anganen, called "Magi." These languages are part of a group called the Mendi-Pole Subfamily, which in turn — along with Wiru, Kewa, Huli, Enga, and a few others — belongs the larger West-Central Family. This family has several hundreds of thousands of speakers. In the northeastern Mendi Valley, people primarily speak Imbonggu (also called Aua), which is mostly heard in Ialibu Subprovince to the east of Mendi. It is a dialect of Hagen, which belongs to the Central Family of languages spoken in the Western Highlands and Chimbu Provinces. These Imbonggu speakers are technically "Mendi." They belong to the Mendi Valley tribes and intermarry with other Mendi.

Mendi Religion and Culture

According to the Christian group Joshua Project 99 percent of Mendi are Christians. Traditionally, they revered their ancestors, believed to influence the living. Before the 1970s, they practiced fertility cults to ensure prosperity, based on legends of male and female beings who shaped the land and humankind. Christian missions, particularly Catholic and United, became prominent in the 1970s–80s, exerting social and political as much as spiritual influence. [Source: Rena Lederman, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Deaths are announced with yodeling cries, followed by mourning feasts (komanda). Gifts are exchanged to elicit mortuary payments (kowar), usually to maternal kin. The dead are buried locally so their spirits (temo) remain nearby. Formerly, ancestral skulls were kept in ritual houses where pigs were sacrificed for healing.

The Mendi hold deep respect for their ancestors, who are believed to influence the fortunes of the living. Before the 1970s, they also practiced fertility cults intended to promote prosperity, health, and human welfare. Among the most striking customs is the mourning practice of Mendi widows. Upon the death of her husband, a widow covers her face with white clay and wears 365 strands of kunai beads—known as “Job’s tears.” Each day, she removes one strand, symbolizing the passage of a year. When the final strand is removed, her mourning period ends, and she may remarry. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Formerly, men with inherited ritual knowledge led fertility cults. Today, some act as sorcery exorcists (nemonk ol), while others—men and women—possess curing or wealth-attracting spells. These practitioners use forest materials and imported goods, receiving small payments. In precolonial times, autopsies and surgeries were performed; now rural aid posts link villages to the provincial hospital, though many still avoid these services for childbirth and other conditions.

Mendi garden Tribes of Papua New Guinea

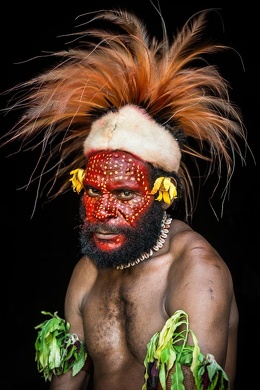

Public ceremonies now revolve around exchanges marking marriage, death, and political alliances. Men display elaborate feathered wigs and body decorations in parades, chants, and oratory rich in metaphor and performance. Songs for courtship and mourning rely on poetic improvisation. Women crochet colorful string bags, and even garden layouts can show artistic flair. The neighboring Wola people emulate the King of Saxony bird-of-paradise in ritual dances, using its plumes in their headdresses.

Mendi Family, Marriage and Kinship

Mendi society life is organized around clans, and marriages are typically exogamous, meaning partners must come from different clans.This practice helps expand social networks and diversify exchange relationships. Young people generally have the freedom to choose their partners, though marriages are still deeply embedded in kinship relations and reciprocal obligations. Marriage ceremonies involve extended exchanges of wealth between the families of the bride and groom, with larger contributions usually flowing from the groom’s side. After marriage, couples typically settle near the husband’s family, and polygamy remains socially acceptable. Divorce, while possible for either spouse, may require the return of marriage wealth. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Household size and composition among the Mendi vary, but most include a husband, one or more wives, their children, and sometimes an elderly parent or unmarried sibling. Some individuals live alone. Men typically reside and garden in their father’s locality, though they may retain rights to gardens in their mother’s clan. Most women continue to garden on their natal land after marriage. Because clan identity is tied to place, clans maintain inalienable rights over garden and forest lands; outsiders may gain temporary use rights but cannot make permanent claims. Fathers redistribute garden plots to their children, and both parents pass on ritual or gendered knowledge. Parents also assist sons with bride-wealth payments. [Source: Rena Lederman, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Young people, who often marry into allied clans. Lineage “brothers” and “sisters” avoid marrying each other, broadening exchange networks. Weddings involve extended wealth exchanges between kin groups, with greater contributions from the groom’s side, which also initiate twem (exchange) partnerships. Postmarital residence is usually virilocal, and polygamy is fairly common. Either spouse may seek divorce, though wealth is usually returned; women often take their children and are welcomed back by their natal clans.

Women and older girls do most childcare, but men also care for small children and often take young sons with them to foster loyalty. Children nurse freely and beyond age three. Parents are affectionate but quick to discipline, and children may answer back or stay with other relatives if they feel wronged. Youth are encouraged to join in gift exchanges. Unlike many Highland groups, the Mendi have no initiation rites. Most children attend local schools, and some continue to secondary or postsecondary education.

Mendi social identity is based as much on locality and food sharing as on ancestry. They identify with their father’s clan but maintain strong maternal ties, both sides actively engaged through exchange. Though called “clans,” these groups are not descent-based but function similarly. Mendi kinship follows an Omaha-type system: father’s brother’s children are classified as siblings, while cross-cousins on the mother’s or father’s sister’s side share a single distinct term.

Mendi Life, Villages, Society and Economic Activity

Traditionally, the Mendi didn’t have true villages; houses were scattered within clan territories, separated by fences from gardens. A typical homestead traditionally included an oval men’s house, a long women’s house (also used for pig stalls), and smaller buildings such as menstrual huts. Newer houses feature separate sleeping areas for men and women. Government “census units” (200–800 people) do not correspond to indigenous localities (su, “ground”), which usually have 20–100 residents. Each su is tied to a single clan or subclan and centers on a communal clearing (koma) used for meetings and ceremonies. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Labor is divided mainly by gender and age. Men clear forests and build fences, while women garden, care for pigs, cook, and manage hospitality. Men sometimes perform women’s work, but not vice versa. Clan events are strongly male domains—men handle pig butchering, feast preparation, oratory, and public displays. Traditional tools such as wooden digging sticks and steel axes remain essential. Women spin fiber for net bags and clothing, and both sexes produce containers, utensils, and weapons. Before colonial rule, Mendi traded extensively beyond their valley. They journeyed several days north to Kandep for salt and pigs, exchanged pearl shells and tigaso oil from the south, and acted as intermediaries moving shells from the coast into the highlands.

Sweet potatoes, the staple food and main pig fodder, are grown in fenced, mulched mounds that can remain productive for decades. About half of all produce is fed to pigs, which are central to wealth exchange and ceremonial life. Greens, sugarcane, and European vegetables are planted around the mounds. Since the 1970s, Mendi have experimented with coffee, cattle, and small-scale trade; some run local stores or transport businesses and seek wage labor in towns.

People identify with their father’s named clan (sem onda) and subclan (sem kank), though affiliation can be renegotiated through residence and cooperation. Clanship entails shared responsibility for defense, contributions to feasts, and aid in marriage and mortuary exchanges. Alongside clan obligations, individuals cultivate twem partnerships—exchange relationships with affines, maternal kin, and others—that provide wealth, autonomy, and influence. These personal networks often crosscut clan alliances.

Local groups are known by both place and clan names (e.g., Senkere Molsem). Clan sections in different areas maintain ties with one another and with allied neighboring clans, forming tribal alliances of up to about 1,500 people. Neighboring tribes—sometimes totaling around 3,000—may call each other “brothers” and merge names (e.g., Surup–Suol). Leadership is achieved, not inherited. Influential men (ol koma or “big-men”) gain prestige through generosity, public speaking, and skill in managing exchange. Success depends as much on personal twem networks as on household productivity or access to female labor. Women are excluded from clan policymaking.

Kewa

The Kewa are a Southern Highlands group also known as Kewapi, Pole, South Mendi and West. They speak three main, related dialects and are known for their agriculture, which includes coffee, and their traditional cultural practices, which mix with their predominantly Christian beliefs. Their traditional practices include rituals, a belief in powerful spirits and ghosts, and traditional medicine using herbs and other local remedies. The ancestors of the Kewa people most likely lived in an area now occupied by the Central Enga people, located well to the north and northwest. There are ancient trade routes that extend southwest to Lake Kutubu and along the Kikori River, as well as northwest to Upper Mendi. The first European visitors were patrol officers Jack Hides and James O'Malley, who penetrated the Kewa area in 1935. There was little contact again until the early 1950s. Since then, both missions and the government have constructed airstrips, schools, roads, and medical facilities. [Source: Google AI]

The Kewa live mainly in the districts of Mendi, Kagua, Ialibu, and Pangia in the Southern Highlands Province. The name "Kewa" is not indigenous and was likely given to them by Australian government officers. The Kewa have traditionally called themselves by the names of their clans or as speakers of an "important language" (adaa agaale). Kewa literally means "a stranger," and refers to people generally living south of Ialibu, the main center from which the first census was taken. The same name, with similar meanings, is found in other parts of the Southern Highlands Province. The Kewa cultural area is located between 6° 15 and 6°40 N and 143°7 and 144°1 E. One major river network, the Mendi-Erave and its tributaries, drains the whole Kewa area. Two prominent mountains, Giluwe (4,400 meters, 14,435 feet) and Ialibu (3,300 meters, 10,827 feet), lie to the north and northeast of the area. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Population estimates from 2000 suggested the total Kewa population was close to 100,000, but other sources suggest a current figure of around 96,000. As of 1989 the estimated population was 63,600 with a density from 15-40 persons per square kilometer, although in some areas it is much less. The population at that time was growing at the rate of 2.7 percent per year, with a fluctuating resident population due to migration out to towns and plantations. In the 18-40 age bracket, 35-40 percent of the People were nonresidents in their village or parish. The major towns in the Kewa area are Kagua and Erave, with Mendi and Ialibu on the northern border. In the 1990s, only Mendi has more than 1,000 permanent residents. ~

Language: The Kewa speak three major, somewhat mutually intelligible dialects: East Kewa, West Kewa, and South Kewa. The Kewa language belongs to the Mendi-Kewa subgroup of the Engan (West-Central) family of languages. The Engan family, in turn, is part of a large group of more than 60 Highlands languages, which are part of an even larger chain of languages crossing Papua New Guinea, West Papua, and Papua, Indonesia. These languages are distantly related and are called Papuan to distinguish them from Austronesian languages. Kewa also shares cultural and linguistic ties with groups to the south and west of Lake Kutubu.

Kewa Religion and Culture

According to the Joshua Project, about 86 percent of the Kewa identify as Christian, most belonging to the Catholic or Lutheran churches. Other denominations present include the Evangelical Church of Papua, Wesleyan, Bible Church, United Church, Nazarene, Pentecostal, and Seventh-Day Adventist. The remaining Kewa are either uncommitted or follow traditional animist beliefs. Despite widespread Christian affiliation, many Kewa maintain a syncretic faith blending Christian teachings with traditional beliefs in ghosts, ancestor spirits, and sorcery. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Traditionally, a belief in a single supernatural being has been common, often linked to the sky deity Yaki(li). Ancestor spirits are thought to be dangerous if not properly appeased, while nature spirits are also feared. Sorcery is widely accepted as real, coexisting with Christian practice. Traditionally, men’s cults with secret languages and rituals held great importance, reinforcing beliefs in spiritual power and fear of ancestral ghosts.

The dead are treated according to their social status: the bodies of important men are placed on raised platforms, while others are suspended on poles. Mourners express grief by covering themselves with clay and pulling out their hair. The spirits of the dead are believed to linger nearby, and the greater the person’s status in life, the stronger their spirit in death. Death is rarely seen as natural—illness or misfortune is often attributed to sorcery. Diseases such as leprosy, malaria, and dysentery were once believed to involve specific curing spirits. The dead are remembered through ceremonies, and some graves are marked with small spirit houses. Myths and stories reflect a strong belief in an afterlife.

Illness is often thought to result from breaking social taboos—improper food preparation, failure to observe sexual abstinence, or disrespect toward ancestors. Healers provide remedies using herbs such as ginger, and health services are now available through aid posts and clinics. Diviners and healers, paid with pigs or chickens, perform cures through incantations, sacrifices, and exorcisms. Sorcery is feared, especially when believed to originate from outside the community, and even hair or nails may be used to inflict harm.

Whistled speech is commonly used, sometimes said to communicate with the spirits of the dead. Traditional instruments include the Jew’s harp, drum, flute, and panpipes. Bamboo is carved into combs and pipes, and body decoration is an art form: faces are painted in vivid designs, and wigs are adorned with feathers from birds of paradise, parrots, cockatoos, and cassowaries. For funerals, people use clay body paint and necklaces made of Job’s tears (Coix lachryma-jobi).

Exchange ceremonies foster social unity, with major festivals culminating in the slaughter of hundreds of pigs. Bride exchanges and compensation rituals occur within clans, while the government now helps negotiate compensation for deaths caused by road accidents. Churches have also incorporated special celebrations and meetings into village life.

Kewa Family, Marriage, Kinship and Society

Traditionally, among the Kewa, once a household unit has been established, the nuclear family has lived together in a single house. Adult men, however, have traditionally spent much of their time in the men’s houses. People from other areas who have obligations to a family may be adopted into it. The term for “family,” araalu, literally means “duration of the father.” Married households have traditionally had separate huts used for menstruation and childbirth. In regard to inheritance, wealth is distributed by the senior adult male. Most property passes to the next brother or brothers, though pigs tended by a wife or daughter remain their own. Land is inherited through the male line, though a man may receive land from his wife’s kin if shortages occur. Before death, individuals announce their wishes regarding the distribution of shells, household goods, and other possessions. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Marriage is clan-exogamous (outside the clan) . Bridewealth is negotiated between the bride’s male relatives (father, uncles, brothers) and the groom’s family. The display and exchange of wealth—pearl shells, pigs, salt, indigenous oil, axes, knives, and money—symbolize the marriage contract; in some regions, cassowaries are also exchanged. The acceptance and redistribution of these gifts are crucial in both marriage and divorce settlements. In the past, girls could marry at puberty and were sometimes promised earlier. While polygyny remains known, most marriages today are monogamous and solemnized under church influence. A new bride usually resides and works with her mother-in-law while the groom builds a house and clears gardens. Ideally, sexual relations begin only after the exchange negotiations are completed. Residence is primarily virilocal (living in the husband’s family home or community), and divorce is relatively common—particularly when there are no children. Including trial marriages and informal unions, as many as half of marriages may end in separation.

Children are raised by mothers and aunts until about eight to ten years of age, when boys begin spending time in the men’s house. Corporal punishment is rare; young children are not considered to possess kone (responsible thought or behavior) until around age six, and parents would feel remorse for punishing a child who might soon die. Boys in the men’s house are expected to listen quietly to the elders’ discussions and stories. Learning occurs mainly through observation and imitation. There are no formal initiation rites, but a boy’s participation in men’s cult activities—beginning around age fourteen—marks his entry into adult male status.

Kin groups are organized around the ruru and repaa. A ruru comprises at least two generations of related male kin, their wives, and children. A repaa is a single family unit that may develop into a ruru over time. Descent and land rights are patrilineal, with priority given to the eldest male. Land claims may extend across distant areas due to ancestral migrations. Traditional land claims are reinforced by planting pandanus and cordyline trees, constructing ditches, or cultivating gardens. Kinship terminology is bifurcate-collateral in the first ascending generation. In one’s own generation, an Iroquois-type system applies: parallel cousins (children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister) are regarded as siblings, while cross cousins (children of a brother and sister) are distinguished by separate cousin terms. Brothers and sisters use gendered sibling terms, but reciprocal terms exist for siblings of the opposite sex. Terms for relatives two generations apart are likewise reciprocal.

A clan (ruru) includes all patrilineal descendants spanning at least two generations. Large subclans take the suffix -repaa from the founding ancestor’s name. Each clan resides within a defined parish, encompassing all those associated with a tract of land. Alliances among clans are formed during warfare or large ceremonies. Leadership is vested in “big-men,” who gain prestige through success in exchange ceremonies, warfare, and accumulation of wealth—especially pigs, shells, and wives. Every clan has at least one big-man to represent it. There is no overarching tribal authority beyond the parish, though influential men are known across regions through trade and alliance networks. Both government and churches maintain their own appointed big-men.

Warfare historically played a key role in establishing land tenure and disputes arose where land or forest resources are scarce. Traditionally, most fighting arose from “payback” killings, often beginning with a dispute between brothers. Maintaining balance in the number of deaths was essential; any imbalance required further revenge. Such retaliatory logic persisted at least into the 1990s. Large peace feasts were once held to restore harmony, during which wealthy men distributed pork and other valuables to strengthen alliances. Today, village magistrates continue to arbitrate lesser disputes, while major cases are referred to government courts. The most serious offenses, including murder, are handled by visiting judges of the national Supreme Court.

Kewa Villages, Agriculture and Economic Life

Present-day parishes and villages have developed around traditional dance grounds as well as mission and government stations. People live in dispersed homesteads organized along patrilineal lines. Several clan groups may share a common ceremonial dance-ground territory, each maintaining its own men’s and women’s houses. In recent decades, nuclear family houses have become the norm. Homesteads are surrounded by fenced gardens, casuarina trees, cordyline plants, and ditches that mark property boundaries, and coffee groves are often present. When gardens are far from the parish center, temporary shelters are built nearby. Traditionally, every five to ten years, a clan has sponsored a large pig-killing ceremony, for which participants construct long, low houses measuring up to 100–150 meters. The men’s house is typically a low, rectangular structure (2–3 meters at the peak, about 1 meter at the sides) with a grass roof, bark walls, and a porchlike communal area where men cook and eat together. Beyond this section are small, slightly raised sleeping platforms, each with its own sunken fireplace. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Kewa have traditionally been subsistence farmers and pig keepers. Their staple food is the sweet potato, which provides roughly 85 percent of caloric intake. Native and introduced taro are also grown. Sweet potatoes are harvested five to eight months after planting, depending on soil and rainfall. In regard to the divison of labor, men are responsible for felling trees, slashing, burning, and tilling, while women assist with clearing grass, planting, weeding, harvesting, and transporting the crop. Women manage gardens, care for pigs, prepare food, and look after young children. They cook in the family residence or bring meals to the men’s house. Men collect firewood, plant sugarcane and edible pitpit, harvest pandanus nuts, hunt, and engage in trade. Women weave net bags, aprons, and thatching mats from pandanus leaves, while men craft bark belts, arm and leg bands, and the occasional leg armor.

Two main garden types are recognized: maapu and ee. The maapu garden is used for sweet potatoes, cassava, sugarcane, and edible pitpit, as well as introduced vegetables. The vines are planted in mounds—circular or rectangular—for drainage and composting. The ee is an older or overgrown garden, often used for greens and leftover sweet potatoes, which also serve as pig feed. Other cultivated crops include cucumbers, beans, corn, cabbage, onions, peanuts, pumpkins, and pineapples. Surplus produce, pork, and fried biscuits are sold in local markets. Two kinds of pandanus are harvested—one with a large nut, the other with a long red fruit. The main cash crop is Arabica coffee, though tea, chili, and pyrethrum have also been introduced. Pigs are the most important domestic animals, central to ritual and exchange, while chickens, cassowaries, goats, and a few cattle are also kept. In some areas, such as Sugu and Erave, endemic malaria restricts land use. Recent government projects have introduced cattle grazing where feasible. Planting trees, digging ditches, and building fences continue to serve as the most effective evidence of land ownership.

Kewa artisans continue to produce a range of traditional tools and crafts, including baskets, arrows, and stone axes. Basket weaving is widespread, using local reeds and vines, often patterned in brown or black. Along the northeastern border, people weave wild cane panels for sale to neighboring groups. Decorative weaving, once used for securing ceremonial axe handles, remains a valued art. Women make umbrella mats, net bags, aprons, and wig coverings, while men produce arm and leg bands, small purses, and carved wooden bowls. Though shields are no longer made or decorated, bows, arrows, and spears are still crafted—sometimes for tourist sale. Industrial and vocational skills are now taught in towns and mission centers.

Trade occurs both within the Kewa area and with neighboring groups. Traditional trade items include gold-lip pearl shells (Pinctada maxima), pigs, and bundles of salt and tigaso oil from the Campnosperma tree, carried in long bamboo tubes from the Lake Kutubu region. Every village maintains small trade stores, usually owned by local clans or subclans, selling axes, knives, rice, tinned fish, matches, pots, clothing, kerosene, and other goods. Kewa men also trade and use the plumes of birds of paradise, parrots, cockatoos, and cassowaries to make elaborate headdresses.

Foi

The Foi people are also known as Fiwaga, Foe, Foi'i, Kutubuans, Mobi and Mubi. Inhabiting the Mubi River Valley and the shores of Lake Kutubu on the fringe of the southern highlands, they divide themselves into three subgroups: 1) the gurubumena, or "Kutubu people"; 2) the awamena, the middle-Mubi Valley dwellers; and 3) the foimena proper, the so-called Lower Foi who reside near the junction of the Mubi and Kikori rivers. The term "Foi" formerly applied to the common language of all three subgroups. It was later employed as the name of the ethnic group by the first missionaries in the Foi region. [Source: James F. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

There were about 10,000 Foi in the early 2020s according to the Joshua Project. The 1979 Papua New Guinea National Census counted 4,000 Foi in their territory and another 400 Foi living elsewhere. Foi territory comprises 1,689 square kilometers (652 square miles), and has population density about 5 people per square kilometer. Most Foi inhabit the banks of the middle reaches of the Mubi River in the alluvial Mubi River Valley at an elevation of around 670 meters (2,200 feet). The region is situated between highlands valleys to the north and the coastal regions of the Gulf Province to the south. The southeasterly monsoon brings considerable rainfall between May August. October and March are relatively drier. To the north of the Foi region are the Angal-speaking groups of the Nembi Plateau; to the southwest are the Fasu or Namu Po people; to the east are Kewa speakers of the Erave River Valley. Directly south of the Foi are small groups of Kasere, Ikobi, and Namumi speakers of the interior Gulf Province.

Language: Foi, also known as Foe or Mubi River, is one of the two East Kutubuan languages of the Trans-New Guinea family. Dialects of Foi are Ifigi, Kafa, Kutubu and Mubi. The estimated number of Foi speakers in 2015 was between 6,000 and 8,000. Foi and Fiwaga are the only Languages within the East Kutubuan Family. They closely related only to the languages of the West Kutubuan Family, which includes the Fasu, Kasere, and Namumi languages. There are a few similarities with other interior Papuan languages such as Mikaruan (Daribi) and Kaluli. ~

Foi tribesemen in Daga Village, Lake Kutubu, black is the color for warriors anyway in away

The Foi likely first entered the Mubi Valley from the southwest, bringing domesticated sago with them. While major warfare between distant villages was not common, sorcery, ambush, and assassination were regular occurrences in the past. The fear of sorcery, revenge killings, and the need to pay high compensation to the victims' families were moderately effective sanctions against violence and homicide in the past. Although they were briefly encountered explorers moving inland from the Papuan Gulf coast regular contact was not established between the Foi and Europeans until Ivan Champion first sighted Lake Kutubu in 1935 and explored the lake on foot during his Bamu-Purari patrol. The Unevangelized Fields Mission began operating at Lake Kutubu and in the middle Mubi Valley in 1951.

By the late 1960s, Christianity had largely replaced the traditional religious life of the Foi. Ethical commandments and the fear of Christian afterlife retribution, passed on by missionaries, have become models and incentives for proper behavior. Today, homicide and violence are rare, and suicide is less common than in the past. From 1950 until the early 1970s, the Highlands were administered from various patrol posts. Then, a new administrative center was built in the Mubi Valley, and government health stations were reestablished. Australian administrators introduced various European and other foreign vegetables to the area, including Singapore taro, pumpkins, chokos, Cavendish bananas, and pineapples. In 1988, large oil reserves were discovered west of Lake Kutubu in Fasu territory. The Foi of the Upper Mubi Valley traditionally traded with and occasionally fought against their Highland neighbors to the north. They exported the reddish oil of the kara'o tree (Campnosperma brevipetiolata), receiving pearl shells, pigs, and axe blades in return.

Foi Religion and Culture

According to the Christian organization Joshua Project, about 95 percent of the Foi identify as Christian. Prior to mission influence, Foi men engaged in a number of ritual cults intended to promote fertility, cure illness, and appease ghosts. All sickness—except that caused by sorcery—was believed to result from the actions of ghosts. Men sought to acquire the ghosts’ powers of magic, foresight, and sorcery for themselves. [Source: James F. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Among the Foi, all dead people become ghosts. The power and malevolence of a ghost depend on the nature of death: those who die violently, especially through homicide, produce the most dangerous and potent spirits, while those who die peacefully are considered weaker and less harmful. Ghosts are thought to appear as certain fruit- and nectar-eating birds, and trees that attract such birds—particularly species of Ficus—are regarded as favored ghost abodes. Ghosts are also believed to gather at sites where powerful spells were once performed, at still pools, and in river whirlpools. In the past, men fasted and slept near such places to establish dream contact with the spirit world. These cult practices disappeared in the late 1960s with the spread of Christianity.

Traditionally, ghosts were expected to depart from the world of the living and journey to an afterworld located in the distant east. This belief now coexists with Christian notions of Heaven. Widows were considered especially vulnerable to the influence of their deceased husbands’ ghosts and dangerous to other men until they underwent purification rituals before remarrying. Ghosts were also thought to act as agents of vengeance—men could send illness to their sisters’ children if dissatisfied with the bridewealth received for them. At the same time, men sought guidance from ghosts through dreams or ritual communication, believing them to be sources of magical power and prophetic knowledge.

Certain men were known for their ability to communicate with ghosts and perform healing rites, earning prestige as spiritual specialists. They also initiated younger men into cult knowledge. Sorcery techniques and their associated substances were often acquired through trade or purchase from neighboring peoples. Mastery of sorcery was closely linked to the authority of big-men.The Usi and Hisare—ghost-appeasement cults of the middle Mubi region—were the most prominent ritual systems. Their practices involved preparing potions, extracting harmful substances from the bodies of the sick, and learning sorcery techniques. Before the 1960s, roughly 60 percent of boys were initiated into the Usi cult. Adult men were also bound by food taboos intended to preserve strength and delay aging by avoiding foods associated with femininity or decline. These prohibitions have largely faded since 1970.

Foi tribesemen in Daga Village, Lake Kutubu, anyway in away

The most highly developed Foi art form is ceremonial song-poetry. Women compose these laments as sago-processing work songs, while men perform them publicly to honor deceased men. The songs use rich imagery that traces the life of the deceased through the sequence of places he occupied and used. The Foi also maintain a large body of myths, told in informal settings for entertainment. By contrast, graphic or visual art is virtually absent.

The Bi’a’a Guabora (“arrowhead cult”) was a secret male fertility cult aimed at ensuring success in hunting. Its rites were performed in conjunction with funerals, widow remarriage ceremonies, and the completion of new longhouses. The usane habora was the major traditional healing ceremony, involving pig slaughter, exchanges of pork and shell valuables, and all-night men’s dances accompanied by drums. The sorohabora was a more secular pig-killing and exchange event celebrating the completion of new longhouses or large canoes. During these ceremonies, men sang laments to honor the dead. In more recent decades, the Foi have adopted the sa pig-killing and exchange ceremony from the Mendi-Nipa region, linking them to the broader regional exchange networks of the Southern Highlands.

Foi Family, Marriage, Kinship and Society

Foi men traditionally maintained one or more bush houses in different parts of their territory, where they and their wives processed sago, tended gardens, and cared for pigs. Children remained with their mothers in the women’s houses until about age two, when boys moved into the men’s house to live with their fathers. Learning was informal — children acquired skills through observation and trial-and-error imitation rather than direct instruction or punishment. A man and his adult sons often lived near one another, allowing their wives to cooperate in gardening and food preparation.Inheritance followed the male line. A man passed on his land, wealth, and property to his sons, whether biological or adopted. [Source: James F. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Traditionally, marriages were arranged by the fathers of boys and girls, often at a very early age. Before missionary influence discouraged the practice, girls could be betrothed in infancy. Today, men wait until a girl shows signs of maturity before making formal inquiries. Upon the presentation of bridewealth — typically pearl shells, cowrie shells, meat, and money — by the groom’s father and maternal uncle to the same relatives of the bride, the girl moved into her husband’s household. Bridewealth payments were often made in installments, sometimes continuing for years after marriage. When a person died, members of the deceased’s spouse’s clan made funeral payments to the father’s, mother’s, and maternal grandmother’s clans. These transfers symbolically canceled any remaining bridewealth obligations. Divorce was rare, and while polygyny existed, it was practiced by only a few men.

Foi tribesemen in Daga Village, Lake Kutubu, red is the color for mature men anyway in away

Foi social organization is based on local, totemically-named patrilineal clans, which serve as exogamous units and vary greatly in size. Smaller, unnamed “lineages,” usually composed of a man and his adult sons, act as units of marriage negotiation, while the larger clan governs exogamy and the distribution of bridewealth. Descent is strictly patrilineal, though orphaned children are sometimes adopted by their mother’s brother.Land is held collectively by local clan segments, though individual members enjoy long-term rights over particular plots, typically inherited from father to son. The Foi use an Iroquois-type kinship system (also known as bifurcate merging), which distinguishes between same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings. A father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are referred to by the same terms as “father” and “mother,” while a father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers are called by distinct terms, often glossed as “aunt” and “uncle.” Parallel cousins (children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister) are regarded as siblings, whereas cross cousins (children of a father’s sister or a mother’s brother) are considered potential marriage partners.

Within each local clan, one or two men — respected for their former prowess in warfare, skill in negotiation, eloquence, magical knowledge, or healing ability — hold positions of authority. Each village typically has two to four such “big-men,” who represent the community to outsiders. Social order depends largely on the recognized wisdom, judgment, and persuasive abilities of these leaders rather than on formal institutions of control. Three or four neighboring villages whose longhouses stand near each other form an extended community. Fewer than 10 percent of marriages occur between different extended communities. Within these units, open warfare was traditionally avoided, though sorcery and homicide still occurred. The extended community served as the basic alliance unit for warfare in the past and remains the political unit for large ceremonial exchanges.

Foi Villages and Economic Life

Most Foi villages are located along the banks of the Mubi River and the shores of Lake Kutubu, and dugout canoes remain the main means of transportation. Villages vary in size from about 20 to nearly 300 people. In the 1990s, over 60 percent of Foi land was reserved for hunting and not permanently inhabited, creating wide buffer zones of uninhabited forest between Foi and neighboring groups. [Source: James F. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Communal life traditionally centers on a men’s longhouse, which houses the representatives of three to thirteen patrilineal, exogamous, and dispersed clans. Women live in smaller dwellings that flank the longhouse, which itself can reach lengths of up to 55 meters. The separation of male and female domiciles reflects the belief that contact with women’s menstrual blood is harmful to men’s health. Despite this division, everyday subsistence revolves around smaller nuclear family bush houses scattered across clan-owned land surrounding the village. A man, his wife or wives, and their children live together at these sites. Families move regularly between their bush houses and the central longhouse, which functions primarily as a ceremonial and communal gathering place rather than a permanent residence.

Foi tribesemen in Daga Village, Lake Kutubu, yellow is the color for initiates anyway in away

Foi subsistence traditionally depends on several interrelated activities, ranked roughly in the following order of importance: sago extraction, gardening, tree crop cultivation (especially marita pandanus and breadfruit), foraging, fishing, and hunting. Pigs are semidomesticated and are killed both for everyday consumption and in large numbers during major ceremonies. The Foi divide the year according to seasonal cycles. With the onset of the rainy season in mid-year, families often leave their villages for hunting preserves, where they trap, fish, and forage until the drier weather returns around October. They then return to their villages to clear new gardens using swidden techniques, process sago, and tend pigs.

Subsistence work is differentiated by gender and age. Women are responsible for processing sago, tending gardens, foraging, checking traps and fishing weirs, caring for pigs and children, and weaving baskets and string bags. Men build houses and canoes, prepare new garden land, manage sago groves, construct traps and weirs, hunt with axe and dog, and participate in trade and ceremonial exchange. In pre-mission times, men also conducted fertility and healing rituals.

Foi men have long maintained active trade relationships with neighboring Highland groups to the north. Traditional exports included kara’o oil, black-palm bows, and cassowaries, which were exchanged for pearl shells and small livestock. In earlier times, ritual knowledge and sacred objects were also obtained through trade. Since the 1970s, the Foi have participated in the Highland-style pork-and-shell exchange cycle, which involves large ceremonial pig kills and the circulation of shell valuables. Over successive ceremonies, debts in pork and shells accumulate, and villages take turns repaying their obligations. These complex events are organized and mediated by influential men who act as the community’s leaders and negotiators.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025