Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

MOROBE PROVINCE

Morobe is a province on the northern coast of Papua New Guinea that contains significant mountain areas. The provincial capital and largest city is Lae. The province covers 33,705 square kilometers(13,013 square miles), with a population of 674,810 (2011 census). After the division of the Southern Highlands Province in May 2012, Morobe province became the most populous province in Papua New Guinea. It includes the Huon Peninsula, the Markham River, and delta, and coastal territories along the Huon Gulf. The province has nine administrative districts. It shares borders with Madang, Eastern Highlands, Gulf, West New Britain, Central, and Oro provinces. [Source: Google AI; Wikipedia]

Geography of Morobe Province is diverse, encompassing highlands, mountains, valleys, and a long coastline along the Huon Gulf. Key features include the Markham River valley, the Huon Peninsula with the Sarawaged and Finisterre mountains, and a 402 kilometer (260 mile) coastline. Other ranges include the Rowlinson Range and the Owen Stanley Range. Mountainous areas have steep slopes, high rainfall and very high soil-erosion rates. The Markham River valley and the adjoining Bulolo River are important for agriculture and livestock. The coastline is rugged, unlike the swampy south coast of Papua New Guinea. Major rivers include the Markham and Waria and to a lesser degree the Watut, Mongi, and Masaweng. The province includes several small offshore islands. The capital city, Lae, has a tropical rainforest climate with high precipitation, averaging around 450 centimeters (180 inches) of rain annually. Temperatures are cooler in the highlands, especially at night, where sweaters or light jackets are recommended.

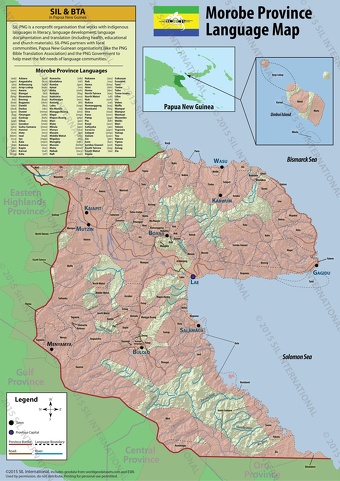

Languages: At least 101 languages are spoken, representing 27 language families, including Kâte and Yabem language. English and Tok Pisin are common languages in the urban areas, and in some areas pidgin forms of German are mixed with the native language. The majority of the indigenous Papuan languages of Morobe Province belong to the Finisterre-Huon branch of the Trans-New Guinea language family. During the 20th century, two well-studied local languages, Kâte and Yabem, were used for the purposes of evangelisation by the Lutheran Church, based in Finschhafen. In theory, Kâte was intended for use in the mountainous hinterlands, where Papuan languages are spoken, and Yabem in coastal and lowland areas, particularly along the coast and in the Markham Valley, where speakers of the Austronesian family of languages predominate. However, in some inland areas such as Wau, both Kâte and Yabem were introduced by mission groups coming from different directions. Today, English, and especially Pidgin English, are the common urban languages in Lae.

Ethnic Groups in Morobe Province include the coastal Austronesian peoples like the Yabem and the mountainous interior's Papuan peoples like the Kote. Ethnic and clan loyalties remain strong., and linguistic diversity is high, with many different languages and dialects spoken throughout the province. The Austronesian group is a broad category, with many groups inhabiting the coast and the Markham River valley. The Yabem is the most prominent group on the coast. The Bukawa, Labu, Musom, and Wampar are other coastal groups. The Gitua live along the Huon Peninsula.The Kapin live along the Middle Watut River. Papuan peoples is a broad category for groups living in the mountainous interior. Kote is one of the main languages spoken in the interior. The Anga once occupied the central mountains. Dedua, Kosorong, Mape, Mesem, Sene, and Yekora are examples of other groups living in the interior. Lae, the largest city, is home to a diverse mix of ethnicities and languages from across the province and from other parts of Papua New Guinea. Lae also has a significant expatriate population.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

Wantoat

The Wantoat, also known as Awara, Wapu, and Wopu, are an ethnic group living in the Wantoat Valley of Papua New Guinea. Like many groups in the region, they traditionally had no collective name for themselves, as they clearly recognized their own territories and neighboring enemies. Expatriates later gave them the name “Wantoat,” after their main locality—the Wantoat River Valley, a tributary of the Leron River, which flows into the Markham River. [Source: Kenneth A. McElhan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

The Wantoat inhabit the rugged southern foothills of the Finisterre Mountains in Morobe Province, at elevations ranging from 360 to 1,800 meters (1,180 to 5,950 feet) , where the climate becomes increasingly temperate with altitude. According to the Christian organization Joshua Project, their population in the 2020s was about 29,000. In 1980, estimates placed the population at roughly 5,500 for the Central dialect, 1,500 for Awara, and 300 for Wapu. Major Wantoat villages include Gwabogwat, Mamabam, Matap, Ginonga, and Kupung.

Language: The Wantoat language belongs to the Finisterre branch of the Trans–New Guinea Phylum. Its dialects include Wapu (Leron) in the south, Central Wantoat, Bam, Yagawak (Kandomin), and Awara. Awara shares only about 60–70 percent lexical similarity with Wantoat and Wapu. Consonant clusters with mixed voicing occur within words. Syllables range from a simple vowel (V) to a maximal structure of CVVC, and stress is distinctive, though it carries a low functional load.

History: The Wantoat homeland lay within the former German colony of Kaiser Wilhelmsland. After World War I, the area came under Australian administration through the League of Nations mandate. The Wantoat were first contacted in 1927 by a patrol led by German missionaries, who began evangelization in 1929 using national evangelists and the Kotte (Kâte) language as a church lingua franca. Rival missionaries from the Kaiapit mission station in the Markham Valley accused them of encroachment, leading to clashes. Eventually, the Wantoat were divided into two mission circuits—one using Kotte (Kate) and the other Yabem as their church languages.

Following World War II, Australian administrative control brought peace, expanded inter-village mobility, increased intermarriage, reduced dialectal differences, improved male longevity, and decreased polygamy. It also enabled the introduction of a limited cash economy and allowed young men to seek employment in towns and on plantations. Development accelerated with the completion of the central Wantoat airstrip in 1956, the establishment of a government patrol post and English-language school, the arrival of trading companies, and the residency of a Lutheran missionary in 1960. The construction of a road connection through the Leron Valley in 1985 further integrated the Wantoat region into the national economy, setting the stage for continued change.

Wantoat Religion

According to the Christian organization Joshua Project, about 99 percent of the Wantoat were Christians. Their traditional beliefs and complex mythology had been based on three major tenets explaining the origin of their people and culture. First, they believed that the center of creation for all peoples of the world — including Europeans — was the Wantoat Valley. Second, at the time of creation, the gods had provided the people with all necessary plants, animals, elements of culture, and, most importantly, the knowledge required for their use. No cultural trait, artifact, or skill was thought to have a human origin. Among these divine gifts were sacred stones from which one could, through ritual, draw power for fertility, healing, and success. Third, because all other peoples had migrated out of the valley, the Wantoat considered themselves the chosen people and the sole keepers of the knowledge and rituals essential for maintaining life and material well-being. [Source: Kenneth A. McElhan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

This belief system, however, was shaken after contact with Westerners. When Europeans arrived with an obviously superior material culture, the Wantoat sought to acquire the knowledge that would enable them to enjoy similar prosperity. When they failed to understand the concepts the Europeans tried to teach, they concluded that foreigners were withholding secret rituals responsible for their wealth. Life thus came to revolve around the quest for these hidden powers. A creator god was said to have retreated to the sun, maintaining contact with humans through insects. Yam gardens were dedicated to this god, and rats were sacrificed in its honor. Culture heroes were believed to have provided people with their culture, and when they died, useful and edible plants were said to have sprung from their bodies. Malevolent spirits were thought to inhabit springs, deep pools, and other striking natural features.

Traditionally, serious illnesses were believed to result either from sorcery or from angered spirits. Sorcery could be neutralized by performing the correct rituals, while evil spirits could be tricked or appeased. With the coming of Christianity, illness increasingly came to be viewed as punishment from God. Traditionally, men had formed a secret male cult from which women were excluded. Ritual knowledge was reserved for men, and the most accomplished among them acted as practitioners who performed sorcery and conducted fertility and healing rites. When missionaries introduced Christianity, it was assumed that men would likewise be the ones educated to perform the new rituals and learn the sacred knowledge.

In traditional belief, every person at birth received a particle of creative force from a general reservoir. After death, this particle became an ancestral spirit, then a spirit of the dead, before eventually returning to the reservoir to be assigned to a new individual. To strengthen their own life force, surviving relatives once exhumed the skull of the deceased and kept it on a shelf at the back of the house. Under Christian influence, the Wantoat later abandoned this practice and began burying their dead in cemeteries.

Wantoat Society and Family

Wantoat men and initiated male youths once lived together in a men’s house, while women and children lived separately. Polygamous men maintained individual houses for each wife, along with their daughters and uninitiated sons. When not with a wife, a man stayed in the men’s house with the younger men. With the shift toward monogamy, the nuclear family became the main household unit, and married men seldom lived apart from their families. [Source: Kenneth A. McElhan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

Marriages were traditionally arranged between clans to balance the exchange of women, preferably through sister exchange. Although many unions were arranged before a girl reached puberty, marriages usually occurred after puberty with older men. A trial period of residence tested the woman’s suitability, followed by gift exchanges and a ritual in which the couple moved into a new house, lit a ceremonial fire, and shared their first meal. Divorce was rare, and polygamy—once common—declined after the end of warfare and missionary bans, giving way to monogamy. With education and outside employment, young people increasingly chose their own partners, which led to more divorces.

Parents were generally permissive, especially with boys. Children learned by working alongside their parents—girls in gardening, childcare, and domestic tasks; boys with men in hunting and building. Male initiation, once the most important rite of passage, was conducted by maternal uncles who taught religious knowledge and gave initiates their first yams and pandanus. Initiated youths then joined men’s work and were considered adults upon marriage. Missionaries later replaced these ceremonies with Christian confirmation, and pastors assumed the teaching role. Today, maternal uncles often assist with their nephews’ and nieces’ schooling.

Kinship and Clans The largest social unit was the patrilineal, exogamous clan, whose members traced descent from a mythical ancestor. Clans formed the center of religious and social life, offering protection and support, though their authority declined with growing individualism. Wantoat kinship followed the Iroquois system, distinguishing same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings: a father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters were called “Father” and “Mother,” while a father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers were “Aunt” and “Uncle.” Parallel cousins were regarded as siblings, and cross-cousins as potential marriage partners. Land was communally owned by clans, with only limited government holdings. Because land rights were collective and few durable goods were made, inheritance was minimal, though prized items like shells, pig tusks, and ornaments were passed from father to sons as spiritually powerful heirlooms.

Before European contact, Wantoat society had no formal classes, though the most successful warrior was most influential. A man’s strength was measured by his children, and about a third of households were polygamous. With European influence, status came to depend on material possessions, particularly vehicles. Clans were the main political units, each led by an elder noted for battle skill and ritual authority. Marriage ties between clans ensured mutual support, and early villages were small, with members spread across several settlements. Modern villages are larger, usually with two cooperating clans led by a council of elders. Clan loyalty shaped social life, and men maintained power through secret rituals. European contact ended warfare and introduced wage labor, weakening clan authority but increasing individualism. Despite this, clan loyalties remained strong, and peace imposed from outside left lingering land disputes.

Wantoat Life, Agriculture and Economic Activity

Traditionally, the Wantoat were farmers who grew sweet potatoes, taro, yams, pandanus, sugarcane, and bananas. Animal protein was scarce, so men hunted marsupials, while today canned fish and meat are purchased. Wild pigs were few, and attempts to introduce European pigs, sheep, or donkeys met little success. European vegetables failed as cash crops due to poor market access, though maize, tomatoes, and cabbages are still grown for local use. The introduction of Singapore (Chinese) taro proved successful, and coffee, promoted by the government and supported by airstrips, became the main cash crop. A new road link to the coast has further improved market access.[Source: Kenneth A. McElhan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Before European contact, people lived in small ridge-top hamlets of 30–80 persons, often separated by hours of walking. Frequent hostilities led to linguistic diversity, with over 25 minor dialects reported. Government policies later consolidated hamlets into larger villages, but this caused sanitation issues, crop vulnerability, and renewed clan tensions. Many people therefore lived part-time in their garden shelters. Today, about 60 settlements remain, averaging around 120 residents.

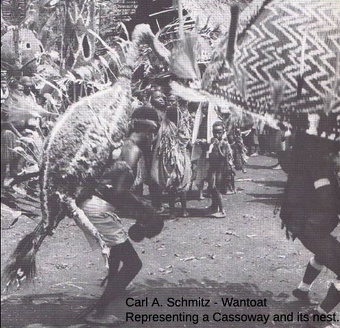

Men and women had distinct roles. Men made loincloths, drums, tools, and ceremonial items, while women wove skirts, string bags, and carried food, firewood, and children. Men cleared land; women tended most crops. European influence did not change these gender divisions. Agricultural rituals once included grand fertility ceremonies, such as breaching mountain dams in sequence to form cascades, and rites invoking sacred stones and creation myths. Artistic expression centered on colorful bamboo dance frames, which were rebuilt yearly. Music was limited to drums and panpipes used in garden ceremonies.

Each local group was largely self-sufficient, crafting tools and utensils from bamboo, wood, cane, and bark. Women wove string bags and skirts from local fibers. Items unavailable locally—such as shells and mats—were obtained through trade with coastal and neighboring inland groups.

Selepet

The Selepet live in Morobe Province in the Valley of the Pumune River, a tributary of the Kwama River, and along the windward slopes of a low coastal range to the north, located on the Huon Peninsula, mainly at altitudes of 900 to 1,800 meters (2,950 to 5,900). They are bounded to the east and west by the more numerous Komba and Timbe peoples. Together these three peoples are separated from the other mountain peoples of the Huon Peninsula by a natural barrier formed by the 3,000-3,900-meter (9,842-12,795-foot) Saruwaged and Cromwell ranges. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 20,000.The 1980 census stated that 3,600 persons spoke the Northern Selepet dialect and 2,700 spoke the Southern Selepet dialect.

The Selepet have a traditional social structure based on patrilineal clans and phratries, with men's houses serving a central role in religious activities, though Christianity has influenced this. The environment they live in ranges from the coastal plain to steep, forested mountains, and their primary language is Selepet. “The name "Selepet" is derived from the sentence "Selep pekyap," meaning "The house collapsed," an event recounted in the story of the people's dispersal from their primordial residential site.

Language: The Selept language is a member of the Western Huon Family, Finisterre-Huon Stock, Trans-New Guinea Phylum of Papuan languages. It has two major dialects: the Northern, spoken along the coastal slopes and the Lower Pumune Valley; and the Southern, spoken in the Upper Pumune Valley.

History: The Selepet’s central location among the mountain peoples proved highly advantageous. When Lutheran missionaries established a station on Selepet land in 1928, they built a school, hospital, and trade store, linking them by road to the coast and opening a route for European goods to reach the interior. Since a regional trade network already existed across the Huon Peninsula, the Selepet quickly became key intermediaries and gained commercial advantage. After World War II, the Australian administration established nearby government stations, and in 1960 built an airstrip, subdistrict office, agricultural center, and English school at Kabwum, in the heart of Selepet territory. As roads expanded into neighboring valleys, the Selepet profited by easily marketing coffee, buying imported goods, and supplying produce to the growing expatriate community. By the 1970s, however, outsiders described them as complacent, since prosperity came more easily than to neighboring groups—a view aligned with their belief that fertility and success came from ancestral blessings rather than hard labor.

Selepet Religion

Today most Selepet are Christians. Traditionally, their religion centered on power and control, concepts controlled by men. Power was believed to exist outside humans, gained through supernatural means—such as from snakes—or inherited from powerful ancestors whose artifacts were preserved. Social control operated through gift exchange, since every gift created an obligation to repay, even from the dead. [Source: Kenneth McElhanon, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Deceased men were buried upright beneath the men’s house with their heads exposed so their skulls could be touched to invoke kinship duties and prosperity. Over time, statues of powerful ancestors were carved, offerings placed before them, and rituals of ancestral blessing spread across villages.

Morobe women

When missionaries arrived with superior material wealth, the Selepet assumed they, too, gained prosperity from ancestral ritual. The New Testament’s reference to God’s “hidden secret” in Colossians seemed to confirm this idea, and discovering that secret became central to life. The Selepet believed spirits inhabited unusual landforms and could cause illness when offended, including the Christian God, who was understood in similar terms. Death enhanced a person’s spiritual role—ghosts first avenged unfulfilled obligations, then granted fertility and prosperity.

Ritual specialists—respected yet feared—performed rites for fertility, healing, divination, and sorcery. When Lutheran missionaries sought to unify diverse groups, they taught all men the Kâte language to conduct Christian rituals. Because women were excluded from sacred roles, Christianity, like the old religion, came to be seen as possessing hidden male knowledge.

Selepet Society, Family, Kinship and Society

Selepet society lacked class divisions; wealth was shared through kinship obligations. Clans remain the key political units, each led by respected elders. Formerly fragmented and often at war, the Selepet now resolve disputes through negotiation, reflecting broader loyalties and peace introduced by European contact.

Before contact, Selepet men and initiated boys lived in men’s houses, while women and children stayed separately. Polygamous men kept a house for each wife. Though monogamy is now common, this division remains, with fathers visiting wives’ homes more often. Childrearing is shared by parents and close kin. Boys assist men with building and hunting, while girls help their mothers with gardening and domestic work. Male initiation once involved circumcision, ordeals, and revelation of cult secrets by maternal uncles. Christianity replaced these rites with church instruction, reducing the uncle’s influence, though they still often fund nieces’ and nephews’ schooling. [Source: Kenneth McElhanon, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Marriage: Traditionally arranged between patrilineal clans to balance the exchange of women, with sister exchange preferred. Marriage was considered final at pregnancy, and today church weddings often coincide with a child’s baptism. Increased mobility and employment allow young people to choose partners and pay their own bride-price, leading to more divorce. Though missionaries banned polygamy, some men still practice it.

Kinship and Clans: Villages contain one or more exogamous, patrilineal clans centered on men’s houses, formerly used for rituals. Loyalty runs from lineage to clan to village. Kin groups share resources, run businesses, and jointly own most land. If a man’s clan lacks land, he gardens on his wife’s. The Selepet use bifurcate-merging terminology—father’s brothers and mother’s sisters are “Father” and “Mother,” while father’s sisters and mother’s brothers are “Aunt” and “Uncle.” Maternal uncles once supervised boys’ initiation. Affinal ties involve avoidance.

Selepet Life, Agriculture and Economic Activity

The Selepet have long been subsistence farmers, cultivating sweet potatoes, taro, yams, pandanus, and coastal crops like coconuts and sago. Hunting provided additional protein, and pig husbandry predated contact. Missionaries introduced cattle, European vegetables, and tropical fruits, now common in local diets. Coffee and copra are the main cash crops. Selepet were key middlemen in regional trade, exchanging inland goods like pigs, taro, and bows for coastal products such as fish, coconuts, and shells. Most people were self-sufficient, skilled in crafting everyday tools from bamboo, palm, and rattan.

Before contact, Selepet lived in small patrilineal hamlets centered on men’s houses. Missionaries and colonial officials promoted centralized villages around churches, but overcrowding caused poor sanitation, land shortages, and conflict. Many families now live in garden shelters, returning to villages mainly for church or administrative visits.

Men and women traditionally made tools and clothing suited to their roles—men crafted weapons, drums, and bark clothing; women made skirts and string bags. Farming remains divided by gender: men clear land and build fences, while women prepare gardens and carry produce.Art was limited to decorated dance headdresses. Ritual dances once celebrated fertility or victory but are now social events led by Christian pastors. Illness was formerly blamed on spirits or sorcery, countered by ritual cures.

Sio

The Sio are an Austronesian-speaking people living on the north coast of the Huon Peninsula in Morobe Province mainly in an area of tropical savanna with patches of rainforest. Also known as Sigaba and Sigawa, they traditionally inhabited a small offshore island but moved to four villages on the mainland after World War II, along with the neighboring village of Nambariwa, which is culturally and linguistically linked. “"Sio" means "they put, take up position," and was adopted by the people themselves, in place of their traditional name "Sigaba" in the early 20th century. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Sio population in the 2020s was 10,000. Their main language is Sio, is an Austronesian language that lacks "close relatives" among the dozens of Austronesian languages spoken by the coastal and island peoples of the region. [Source: Thomas G. Harding, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The interior peoples were the Sio’s traditional enemies, in contrast to their island and coastal neighbors, with whom relations were largely peaceful and based on trade. The Sio maintained a primarily defensive military posture; their island settlement provided natural protection, and garden work on the mainland was carried out by large cooperative groups able to defend against raiders.

A Sio youth abducted by German officials later played a key role in establishing peaceful relations between the Sio and Europeans during the German colonial period (1884–1914). A Lutheran mission was founded at Sio in 1910, and the same man—by then a village headman—led the community’s mass conversion to Christianity in 1919. Subsequent leaders preserved local control over land and resources while maintaining active engagement with outside institutions. A government school and a cooperative for marketing copra and coffee, both initiated by Sio efforts, opened in 1959. The community joined a local government council in the mid-1960s, and by the 1980s had launched new ventures including cattle ranching, a logging partnership with an Asian firm, and cocoa cultivation to offset the decline in copra prices.

Religion: According to the Christian organization Joshua Project, 98 percent of Sio people are Christians. The Sio converted collectively to Lutheranism in 1919, following the arrival of German missionary Michael Stolz in 1910. This conversion spurred the development of a written form of the Sio language and the translation of religious texts.

Traditionally, Sio belief centered on ancestral ghosts—patron deities of men’s clubhouses—and forest-dwelling spirits. The ghosts were vengeful beings who, though appeased by pig sacrifices, punished breaches of social norms with illness and death. Spirits, usually envisioned as hairy dwarfs but also appearing as animals or objects, were unpredictable; sometimes malevolent, they might also reveal themselves in dreams and impart magical knowledge in exchange for the observance of taboos. An inactive creator deity, Kindaeni, was said to have formed the universe.

Magic and ritual knowledge permeated daily life, guiding activities such as gardening, love, trade, healing, weather control, and protection from theft. The recently deceased were believed to linger in the village, causing misfortune until a ceremony induced their departure to the land of the dead—coastal bluffs several miles to the southeast. All deaths were attributed to supernatural causes, often sorcery, and divination was employed to identify the culprit’s community. Esoteric knowledge of myths, magic, and divination was highly valued, and many men held exclusive knowledge acquired through inheritance or purchase. The big-men who led clubhouse groups were typically specialists in yam magic, and their wealth in valuables enabled them to employ sorcerers.

Sio Family, Marriage, Kinship and Society

The nuclear family is the primary domestic unit of the Sio. The Sio have tended to be endogamous, meaning marriages generally occurred within the village or clan. Individuals with common great-grandparents were prohibited from marrying. Lineages were exogamous, and those whose fathers or grandfathers had been associated with the same men’s house—regardless of genealogical connection—were likewise forbidden to marry. Bride-wealth, usually in pigs and valuables, was assembled from a wide circle of relatives and symbolized respect for the bride. Women’s social status was relatively high, and marriage resembled the egalitarian, companionate model found in Western societies. Postmarital residence was typically patrilocal (in the husband’s family home or community), though exceptions were common.Polygyny was socially acceptable and was largely limited to big-men. Divorce under traditional circumstances was said to be rare. [Source: Thomas G. Harding, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Traditional male initiation ceremonies, in which maternal uncles played a key role in instructing youths in “the laws,” lapsed during the 1920s. Thereafter, mission schools—and, from 1959, a government school—provided primary education. Inheritance was patrilineal (through the male line), although living men often gave pigs, valuables, and productive trees to their sisters’ sons. Pottery skills, tools, and decorative patterns were passed from mother to daughter.

Every Sio belonged by birth to a patrilineal descent group (lineage). There was no indigenous term for “lineage,” nor were lineages named; instead, they were identified by the names of their heads, usually firstborn sons. The lineage functioned primarily as a custodial landholding group and seldom acted collectively. Male members tended to live in residential clusters and frequently cooperated in gardening, house construction, and other tasks. Ownership of named tracts of land was vested in patrilineal lineages, each headed by a senior man known as the tono tama (“father of the land”). His knowledge of genealogy and land history was crucial in resolving disputes. Land for gardening was generally abundant, and disputes were uncommon. Because gardening teams often included affines or maternal relatives, people frequently enjoyed temporary use rights to land belonging to other lineages.

Sio society was viewed as a community of kin sharing a common language, culture, and territory, clearly distinguished from neighboring peoples. The population was divided into two residential moieties that maintained a friendly rivalry. Within each moiety were landholding patrilineages whose men once occupied men’s clubhouses. These were centers of ancestral cult activity and arenas for competitive exchanges of yams and pigs, as well as for the pursuit of vengeance—or compensation—for deaths or injuries inflicted by rival groups. Much of social life revolved around the relationships that bound these groups together, particularly those between affines, maternal uncles and nephews, and age mates (formerly, men initiated together in youth).

Traditional leadership combined both ascribed and achieved elements. Leaders were typically firstborn sons, heads of men’s houses, and lineage heads. They were also expected to excel in gardening, craftsmanship, trade, oratory, diplomacy, warfare, and competitive feasting. Those who distinguished themselves in these areas—often with the support of their wives and kin—became recognized big-men, whose influence extended throughout the community.

Sio Villages, Life and Economic Activity

For two to three centuries the Sio lived on a small offshore island later called the “Dorfinsel” by German colonists. The island settlement was divided into residential wards, each densely packed with houses typically shared by two or three nuclear families. Every ward also maintained a men’s ceremonial house. The island village was destroyed during World War II and never rebuilt; instead, the Sio established four mainland villages near the sites of prehistoric settlements. The houses are rectangular pile dwellings roofed with sago-leaf thatch. Similar structures once served as men’s clubhouses, but these were not reconstructed after the war, marking the end of the traditional men’s organization and its initiation rituals. [Source: Thomas G. Harding, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Men have traditionally performed most of the labor associated with yam cultivation, pig hunting, canoe and house construction, and festive cooking. Women made pottery, wove net bags, tended pigs, and managed daily cooking. Both men and women fished—using different techniques—and both participated in preparing and selling copra. Cooperative labor extended beyond the household primarily during the annual pig hunts and in building houses and canoes. Traditionally, teams of three to six men used digging sticks to prepare the ground for planting; aside from this heavy work, household labor sufficed for most agricultural tasks.

Shifting cultivation, centered on yam production in fenced grassland plantations divided into household plots, absorbed the largest share of domestic effort and formed the basis of subsistence. Secondary crops included bananas, taro, sweet potatoes, edible pitpit, sugarcane, and introduced plants such as squash, manioc, and corn. Important economic trees were coconut, sago, betel nut, and pandanus. Cattle have been added to the traditional domestic animals—pigs, dogs, and chickens. Fishing by various techniques and reef collecting made substantial contributions to the diet. The only productive form of hunting was the ritualized feral-pig hunt, carried out with fire, dogs, and bows and arrows during the annual burning of grasslands that preceded planting. Beginning in the late 1930s, expanded coconut planting became a principal source of cash income. Attempts to grow dry rice, peanuts, and coffee proved unsuccessful, while more recent efforts have focused on timber extraction, cocoa, cattle raising, and wet rice cultivation on cleared hillsides.

The rainy season of the northwest monsoon once heralded the major ceremonies of male initiation and large-scale food and pig distributions, through which big-men—leaders of men’s houses—competed for prestige. Dances performed at all major ceremonial occasions incorporated drums, songs, and elaborate headdresses and body decorations. Carving and painting were most highly developed in canoe art, particularly on the prows and side planks, though decoration adorned many utilitarian objects. Musical instruments and sound-makers included wooden hand drums, conch trumpets, and bullroarers.

The Sio participated in a regional exchange network, trading their pottery for inland products such as taro, sweet potatoes, and wooden bowls. Principal crafts included pottery—cooking pots made by women using the paddle-and-anvil technique—and the construction of outrigger canoes. Many everyday items, including stone axes, mats, wooden bowls, bark cloth, bows and arrows, and drums, were obtained through trade. External exchange alleviated seasonal food shortages and introduced a range of goods, some of which were subsequently retraded. Pots, fish, and coconuts were exchanged for root crops from the interior. In Sio understanding, pottery formed the foundation of their trading economy, linking them not only to inland groups but also to neighboring coastal peoples and the Siassi Island seaborne traders who visited twice a year.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025