Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

NINGERUM

The Ninggerum people live in Papua New Guinea's Western Province, with lands historically extending across the border into South Papua (formerly part of Irian Jaya) in Indonesia. Also known as Kai, Ninggiroem and Ninggirum, they are known for their traditional language (Ninggera), therapeutic knowledge and animist-Christian religious beliefs. The Ninggerum are also associated with a town and rural local-level government (LLG) called Ningerum, which is located on the Kiunga-Tabubil highway. [Source: Google AI]

When first contacted by Westerners, the Ningerum had no single name for themselves; instead, each group identified by its local clan name. The term Ningerum was introduced in the 1950s by Dutch colonial administrators, adapted from the Muyu word Ninggiroem (or Ninggirum), referring to closely related groups who speak mutually intelligible dialects of the same language. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Ninggerum, Kativa population in the 2020s was 11,000. In the 1990s, there were about 4,500 Ningerum people. Over 3,300 lived in Kiunga District (Papua New Guinea) and about 1,000 lives in Kecamatan Mindiptana in what was then Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Some Ningerum have migrated to Daru, Port Moresby, Merauke, and other urban centers. The population density in the 1990s ranged from 7 persons per square kilometer in the south of their territory to less than 2 in the north. At the time of Western contact, the population may have reached 6,000, but the region suffered population decline following numerous influenza epidemics in the 1950s and 1960s. ~

Language: The primary language of the Ninggerum is Ninggera, also known as Ninggerum. With at least four dialects, it is classified as a member of the Lowland Ok subfamily of the Ok family of non-Austronesian languages. Its closest links are with the North and South Kati languages spoken by the Muyu and Yonggom peoples, although these languages are unintelligible to monolingual Ningerum speakers. In addition to phonological and traditional vocabulary differences among these dialects, contemporary linguistic patterns are influenced by recent borrowings from three contact languages: Motu in the south, Tok Pisin in the north, and Malay in the west.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FLY RIVER PEOPLES — GOGODALA, BOAZI, KIWAI — AND THEIR LIFE, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

KERAKI OF THE TRANS FLY REGION: LIFE, SOCIETY AND SODOMIST INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

KALULI (BOSAVI): HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

MOTU — THE PORT MORESBY AREA PEOPLE — AND THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GEBUSI, PURARI, OROKOLO ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

OROKAIVA AND MAISIN PEOPLE OF ORO PROVINCE IN SOUTHEAST PNG ioa.factsanddetails.com

Where the Ningerum Live

Traditionally, the Ningerum inhabited the region northeast of Ningerum Station in the Kiunga District of Western Province. Today, most live within the Ningerum Local Level Government (LLG) area, between the Ok Tedi and Ok Birim rivers. Their homeland lies in the rain-forested ridge country forming the southern foothills of the Star Mountains. The Ok Mani River, located just south of the Ok Tedi gold and copper mine, and the rugged terrain beyond the Ok Kawol mark the customary northern boundaries of their territory. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

This interior lowlands region is almost entirely cloaked in dense rainforest except where gardens have been cleared. Elevations range from about 100 meters (328 feet) in the south to over 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) at the northern hilltops, though most of the land lies below 500 meters. The landscape is dominated by steep, north–south ridges divided by narrow, V-shaped valleys with numerous rivers and streams. Swampy areas are common in the southern valleys, where the terrain is less rugged.

The climate is humid and tropical, with annual rainfall exceeding 250 centimeters (100 inches). Temperatures average between 20°C and 33°C (68̊F and 91.5̊ F), slightly cooler in the north. Distinct wet and dry seasons shape both the environment and traditional subsistence patterns.

Ningerum History

The Ningerum first came into contact with outsiders in the early twentieth century, initially through Indonesian bird-of-paradise hunters, and later via Dutch and Australian administrative patrols. For roughly fifty years, these encounters were infrequent and had little lasting influence. Regular government patrols began only in the 1950s, when Dutch and Australian administrators started visiting Ningerum villages more consistently. During this time, village constables were appointed to maintain order and enforce colonial authority, while Dutch officers oversaw several settlements near the border. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Before government “pacification” in the 1950s, intergroup violence was a persistent threat. Small-scale raids were common, often triggered by accusations of sorcery following an unexpected death. Raiding parties usually targeted a single individual believed responsible. Although the introduction of colonial rule curtailed open warfare, it did not eliminate social tension; instead, traditional hostilities became expressed through increased fear of sorcery and more frequent accusations of “assault sorcery.” In recent years, such accusations have often been directed toward close kin—especially brothers and parallel cousins (the children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister).

Following the international border agreement between the Dutch and Australian governments, boundary markers were installed in four Ningerum villages in 1962. Soon afterward, residents of these communities were forced to relocate, choosing whether to live in Irian Barat (now Indonesian Papua) or in the Australian-administered Territory of Papua. The Ningerum Patrol Post was established in 1964, and for several years, government patrols visited the area two or three times annually. However, by the mid-1970s, these visits became infrequent, leaving people on both sides of the border feeling largely neglected.

Exploration and test drilling in the nearby Star Mountains brought sporadic bursts of outside activity, followed by long periods of isolation. The construction of the Ok Tedi Mine in the 1980s marked a turning point, transforming the region with the establishment of major townships at Tabubil and Kiunga. The mine brought extensive contact with expatriates, rapid commercial growth, and severe environmental damage to local rivers. The long-term social and ecological consequences of these developments for the Ningerum people remain uncertain.

Ningerum Religion

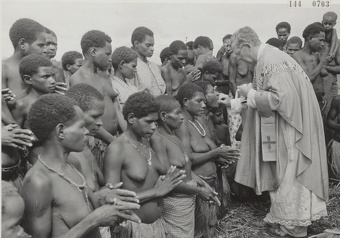

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 90 percent of Ninggerum are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent. In the 1990 an estimated 40 percent of Ninggerum identified as Christian, Initially missionary activity was slow to take root and limited in its influence. Montfort Catholic catechists began working in a few villages in the late 1960s. The Evangelical Church of Papua has sponsored teachers since the late 1970s. Even now traditional religious practices and beliefs remain strong and many blend Christianity with traditional animist beliefs.

Traditionally, Religious life among the Ningerum centered on men’s cult rituals devoted to honoring the spirits of deceased male relatives. These ceremonies reaffirmed kinship ties between the living and the dead and helped maintain social balance within the community. The Ningerum also believed in a range of spiritual beings, including culture heroes (ahwaman), bush spirits, and powerful natural essences that influenced human affairs for both good and ill. Magic was used to affect the natural world—whether to ensure success in hunting, gardening, and feasting, or to cause harm through acts of sorcery. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Ritual Specialists, or men’s cult leaders, presided over ceremonies that celebrated and released the spirits of the dead, often involving the exhumation of bones. The Ningerum also recognized a number of specialized healers, though there were no general-purpose shamans or “medicine men.” Each healer typically knew one or two ritual therapies, each directed toward specific afflictions or causes of illness.

Traditional healing focused primarily on spiritual causes of illness, such as ghost attacks, spirit aggression, or sorcery. Assault sorcery was considered incurable, while projection sorcery—caused by harmful substances magically introduced into the body—could be treated through ritual extraction. Curing rites often had the broader social effect of strengthening communal harmony. Few traditional treatments relied on herbal remedies. Since the late 1960s, government aid posts had offered modern medical care, but Ningerum people often combined these services with traditional healing practices.

Ceremonies were important. The most significant public events were large pig feasts and men’s cult feasts, often held together. These gatherings took place in special feast compounds containing a large ceremonial house and an open plaza with sleeping quarters for hundreds of guests—sometimes up to 700. Preparation could take six months or more, and feasts were hosted by a clan segment roughly once every decade. While their public purpose was to redistribute pork, they also served to honor the dead and reinforced the prosperity and prestige of the host group. Men’s cult feasts followed similar patterns but were additionally linked to male initiation rites.

Death and Afterlife: Upon death, it was traditionally believed, a person’s soul left the body but remained near its living relatives, continuing to influence their lives. Ghosts could punish wrongdoing or neglect among kin by causing sickness, but death itself was never attributed to ghosts. Deaths of the very young, the elderly, or the frail were explained by physical weakness, whereas deaths of healthy adults were almost always blamed on sorcery.

Ningerum Family and Marriage

Traditionally, among the Ningerum, an extended family of up to thirty people lived together as a cooperative domestic group. A household typically consisted of two or three brothers, their wives and children, and a few other close relatives. With the end of intergroup raids and the subsequent formation of villages, these extended family units became smaller, often comprising only a nuclear family along with a few additional members such as a grandmother, foster children, or unmarried siblings. Over time, the nuclear family emerged as the principal domestic unit, though there was always space to include unattached kin—particularly orphans and young single adults. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Parents generally adopted a permissive approach to child-rearing, scolding or threatening misbehaving children only occasionally. Ghosts, spirits, and sorcerers were often invoked to frighten young children into proper behavior. Up until the opening of the Ok Tedi copper mine, there had been few opportunities for formal schooling or public education.

Marriage with a matrilateral cross-cousin—that is, a cousin on the mother’s side, the child of a brother and sister—was preferred, although few unions occurred between actual cross cousins. Most spouses were regarded as classificatory cross cousins, a relationship category that allowed considerable flexibility since knowledge of second- and third-generation genealogies was often limited. More important than strict genealogical rules was the preference for marriages within nearby households, which helped consolidate landholdings and strengthen existing alliances.

Polygyny was accepted but had been more common in the past; the most influential men sometimes had four or five wives simultaneously. Divorce was possible but extremely rare, as marriages generally involved strong emotional bonds between husband and wife. Substantial bride-price payments were required for marriage, with a large initial payment followed by smaller installments that continued throughout the duration of the marriage.

Inheritance: Children primarily inherited land from their father but retained certain rights through their mother. Valuable trees such as sago, breadfruit, and nut trees were usually apportioned among children by their owner before death or, if no instructions were given, divided among heirs afterward. Portable wealth was rarely sufficient to cover death payments owed to the deceased’s matrilineal kin and creditors, and these debts were inherited jointly by the deceased’s adult sons and sometimes by his brothers—or by a husband, in the case of a deceased woman.

Ningerum Society and Political Organization

Ningerum social and economic life had traditionally been based on kinship and patrilineages, with social relations centered on maintaining a network of alliances between a local clan segment and its surrounding segments. Before pacification, these alliances formed a protective circle around each isolated household. Such ties consolidated land rights and reduced resource shortages for local groups. A complex web of social obligations—including ongoing bride-price, child-price, widow-price, death and burial payments, and other personal debts—helped sustain positive relations among neighboring allied families, provided that token payments continued to be exchanged from time to time. In later years, allied families cooperated in activities such as feasting, ritual observances, house building, and fence construction. In the past, they also supported one another in warfare and raiding. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Traditionally, there had been no centralized authority or hereditary leadership extending beyond the extended family household. Political authority within a large household was often nominal. Influential men (kaa horen), usually elder members of the local clan segment, tried to guide their kin through persuasion and example, but they had few formal means to enforce their will. In more recent times, a man of influence could attract followers from clan segments related to him by blood or marriage, though such ties provided only weak political cohesion, and relatives often ignored his advice. In the 1950s, the Australian administration appointed village constables (mamus) in most settlements. Although these men were generally selected because of their prominence, even official backing did little to strengthen their authority or create broader political unity. The Ningerum Local Government Council, established in 1971, introduced elected councillors to represent two or three villages each.

In principle, conflict was not supposed to occur within a local clan segment, yet disagreements—often leading to accusations of sorcery among close relatives—were not uncommon. There were no formal courts to resolve such disputes, and in earlier times a household or clan segment, sometimes joined by allied individuals, would attack another household to defend its rights. In the modern era, fear of sorcery and government intervention functioned as the main forces maintaining village cohesion.

Ningerum Kinship and Land

Each Ningerum individual was born into the named patrilineal clan (kawatom) of his or her father. Clans were tied to specific territories and to one or more men’s cult ritual sites, which were located deep in the forest, out of sight of women and children. There were more than 200 local clans, and only the smallest of these were strictly exogamous. Several clan segments often shared myths describing their descent from a single (usually unnamed) ancestor. As corporate groups, local clan segments included many nonagnates—most commonly wives and a variety of coresident relatives from other clans. In practice, residence played a greater role in determining membership and rights within the group than formal clan affiliation by birth. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Kinship Terminology followed the Omaha type, in which relatives were classified according to descent and gender. A person’s father and his brothers were referred to by the same term, as were the mother and her sisters. Marriages typically took place between members of different clans within the wider community. The Omaha system resembled the Crow system, except that Omaha descent groups were patrilineal rather than matrilineal.

Land Tenure: All land was associated with a named patrilineal clan segment and, in theory, was owned collectively by that group. Fallow garden plots were usually considered the property of the male heirs of the last man to have cultivated them. These rights were often shared among brothers or cousins, though in areas where land was scarce, men might divide their holdings among their sons. Daughters retained usufruct rights and could cultivate the land with their husbands if they lived nearby. Usufruct rights to garden land were sometimes granted to friends or kin as a way of incorporating nonagnates into the local clan segment. After a generation, such land generally became more closely associated with the family of the most recent cultivator than with the original owner.

Occasionally, parcels of garden land were alienated from their original clan segment through purchase with shell money. Rivers, ritual sites, and hunting grounds—as well as the flora and fauna associated with them—were owned collectively by the clan segment, whose interests were overseen by its elders. Land belonging to dwindling or extinct clan segments could be taken over by anyone able to make productive use of it and who could claim usufruct rights through nonagnatic kinship, past residence, or ancestral ties to the land.

Ningerum Villages, Art and Daily Life

Ningerum settlements were small hamlets located on clan territories near gardens, sago swamps, and hunting lands. Most hamlets consisted of a single extended-family dwelling (am or hanua) built as a tree house 5 meters or more above the ground. Houses were rectangular, with separate sections for women and men. Each section contained two or more hearths. About every five years, houses were rebuilt near new gardens. Beginning about 1950, Ningerum began forming Villages (kampong) at the encouragement of Dutch missionaries. At first these villages comprised only a few houses, but they gradually increased in size with the encouragement of Australian officials. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

In the 1980s there were thirty-two Ningerum villages in Papua New Guinea, ranging in size from 29 people (in two houses) to 350 (in more than fifty houses). Like customary hamlets, most villages have periodically moved following epidemics or intravillage conflict. In Irian Jaya, the Indonesian government encouraged even larger villages (desa). Village formation has not led Ningerum to abandon their customary residences; most families have both an isolated bush house, near their gardens, and a village house. Individuals and their nuclear families continue to reside with extended families, but they may live with different sets of relatives in their village and bush houses. Most Ningerum consider their bush house as their primary residence but spend two to three days in the village each week.

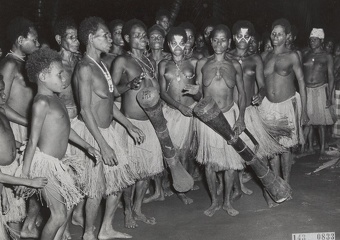

Ningerum art is focused on decorating the human face and body for a variety of dances and ceremonies. They have few carvings or plastic arts, although formerly they carved and painted hand drums and probably had large painted shields. They have a variety of traditional songs and dances, many of which use drums or other simple percussion instruments. ~

Most gardening is a cooperative effort involving a husband and his wife (or wives), often assisted by coresident kin. Women process sago in small groups after a tree has been cut down and opened by men. For tasks that require a great deal of labor — such as house building or clearing and fencing gardens — families often invite twenty to thirty relatives and neighbors to help, reciprocating with an Elaborate meal. Only men hunt with bows and arrows or shotguns, usually by themselves. Both women and men go diving for fish in streams (using fishing arrows and goggles) in small groups. Women do most of the cooking, child tending, and firewood gathering, although men often assist when women are busy with other work. The only cooperative subsistence activity involving large groups (up to 100 men, women, and children) is the occasional use of derris root to poison large numbers of fish when streams are low. Major feasts involve the cooperative effort of two or more local clan segments — occasionally a village — but most construction and food Production for these events is done by a small group of closely related men and women, respectively. Up to 1980, few Ningerum were regularly earning cash wages, and this was almost exclusively a male domain that usually required moving to an urban center or plantation (up to about 1970). ~

Ningerum Agriculture and Economic Activity

Among the Ningerum, extended-family households traditionally formed the basic units of both production and consumption. Daily subsistence centered on sago and bananas, which were the primary staples. These were supplemented by a wide variety of other crops, including sweet potatoes, taro, yams, breadfruit, okari and galip nuts, leafy greens, sugarcane, pitpit, pineapples, and assorted local fruits. Until the construction of the Ok Tedi copper and gold mine, small red chili peppers (lombok) were the only cash crop, grown in limited quantities. The advent of the mine brought major changes to the local economy, opening up opportunities for wage labor and commercial vegetable production for sale in mining settlements and nearby towns. [Source: Robert L. Welsch, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

In the southern regions, two main types of gardens were maintained: large banana gardens, sometimes covering up to two hectares, and smaller mixed gardens, which were fenced to keep pigs out. Banana gardens required minimal upkeep beyond felling trees and planting suckers around the fallen trunks, while mixed gardens demanded considerable labor for fencing, soil preparation, weeding, and general maintenance. Productive for about two years, gardens were then left fallow for fifteen years or more to restore fertility. Sago was abundant in the south, where it was managed through selective weeding and cutting to increase yield. In the north, however, sago was less common, and people relied more heavily on the monocropping of taro as a staple.

Domesticated pigs roamed freely in most villages, foraging for much of their own food. In the evenings they were given small amounts of food to prevent them from joining wild herds. Boars were typically gelded, while sows were serviced by feral males. Pork played a vital role in the Ningerum diet—particularly during the dry season, when pig feasts and ceremonies were frequent. In the wet season, pigs were easily tracked and hunted using shotguns or bows and arrows. Hunting for marsupials and birds provided only a minor supplement to the diet, though small fish and crayfish were often caught in abundance. Forest foraging also contributed delicacies such as sago grubs, frogs, bird eggs, ant larvae, and other small game, but these remained occasional rather than staple foods.

Traditional crafts included the making of string bags, rush skirts, bows, and arrows. Most household utensils were simply made from local bush materials. Men occasionally constructed dugout canoes, used mainly for crossing larger rivers. Houses were built either high in the trees or on shorter posts in village settings. Floors were made from narrow palm slats, roofs from sago-leaf thatch sewn into panels, and walls from the stems of sago fronds.

Trade played an important role in Ningerum social and economic life, especially during large pig feasts, which brought together Ningerum, Yonggom, and Muyu peoples from a broad area. These exchanges involved numerous small transactions in both goods and knowledge. Commonly traded items included string bags, bows, rushes for skirts, red ocher, dogs, piglets, cassowary chicks, and magical or ritual knowledge.

Money cowries, nassa shells, and dogs’ teeth served as standard media of exchange throughout the region. Some men also undertook long-distance trading expeditions, reaching as far west as Mount Koreom and northward into the Star Mountains. In the lowlands, trade lacked specialization; individuals exchanged whatever goods they had in surplus for those they needed but could not easily produce or obtain from relatives. By contrast, trade with the Star Mountains peoples was more specialized. Ningerum black-palm bows and shells were exchanged with the Wopkaimin for tobacco and hand drums, which in turn were obtained from the Tifalmin farther north.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025