Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

GROUPS IN THE CENTRAL HIGHLANDS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA

faces from Papua New Guinea From Kalakai Photography on Facebook

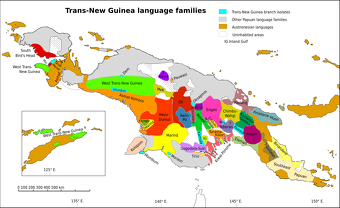

The central highlands of Papua New Guinea are home to hundreds of ethnic groups and is one of the most linguistically diverse regions in the world, with each group speaking its own Papuan language. Well-known Highland tribes include the Chimbu, Enga, Foi, Hewa, Huli, Kalam, Kaluli, the Maprik Tribes, the Sepik Tribes and Tambul Tribes. At one time about 39 percent of the population of Papua New Guinea lived in the highlands. One reason for this might have been the fact that people from Papua New Guinea are susceptible to malaria. Unlike African blacks they lack the sickle cell gene which protects them from malaria. There are less malaria mosquitos in the Highlands.

Archaeological evidence from the highland regions indicate that the area has been occupied for as long a 30,000 years, possibly 50,000 years ago, with agriculture possibly developing 8,000 years ago. The introduction of the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) in the 1700s enabled the cultivation of plentiful amounts of food at higher altitudes, subsequently increasing the population of the area.

On the southern face of the Highlands are Anga speakers and Papuan plateau peoples. In the high central mountains are the Mountain Ok peoples. High Sepik tribes live along the Sepik River and its tributaries. Peoples throughout this zone were preoccupied with ideas about growth and the physical fluids and substances (semen, vaginal fluids, and menstrual blood) that they regarded as agents of reproduction and growth.

The Baruya are a tribe in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. They have been studied since 1967 by anthropologist Maurice Godelier. He said their most sacred secret was that the young initiates, as soon as they enter the house of men, are nourished with the sperm of their elders, and that this ingestion is repeated for many years with the aim of making them grow taller and stronger than women, superior to them, capable of dominating them and leading them.” The practice is extinct: “This custom is no longer practiced today: it disappeared almost immediately after the arrival of the Europeans in 1960”.

The Hagahai, a group of seminomadic highlanders largely unknown to the outside world until 1983, were in danger of dying out. In 1984 there were only 294 members left and there numbers were declining steadily. In 1988 a full-time medical worker was hired to live with them and administer vaccines and antibiotics against the diseases that threatened them. Their population began to rise. But when the medical worker left Hahahai began dying again. In 1990 an airstrip was cleared out of the jungle to allow them ship out harvested coffee. Peace Corp workers were assigned to teach them to read and write. A medical anthropologist who worked with the Hagahai says she is not worried about the cultural intrusions: "There's no way they'll survive without change." [National Geographic Geographica, July 1990].

RELATED ARTICLES:

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Highlands of New Guinea

The Highlands Region of New Guinea extends from the west to the southeast and is entirely landlocked. The highest point in the Highlands and Papua New Guinea is Mount Wilhelm (4,509 meters, 4,793 feet). It is located is the Bismarck Range, which is part of the Central Range. The highest mountain on the island of New Guinea is Puncak Jaya (4,884 meters, 16,024 feet), located in the Indonesian part of the island. It is also the highest peak in Oceania.

The Highlands also contains dense rain forests and enclosed upland basins that are usually 1,370 meters (4,500 feet) or higher. The basins contain lake deposits, formed by soil washed down from the surrounding mountains and trapped by impeded drainage. The soil often contains layers of volcanic ash, or tephra, deposited from nearby volcanoes, some of them recently active, are usually very fertile. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica]

The Highlands Region is one of four regions of Papua New Guinea. Administratively, it is divided into seven provinces: 1) Chimbu (Simbu); 2) Eastern Highlands; 3) Enga, 4) Hela, 5) Jiwaka, 6) Southern Highlands and 7) Western Highlands. The Central Highlands is a major agricultural area, with sweet potatoes being the main staple crop. Cash crops like coffee are also important. Mineral wealth includes copper and gold. There are significant mining operations in Papua New Guinea. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bob and Robin Connolly, Australian documentary filmmaker, made three documentaries in the Highlands in the 1980s. The initial one, First Contact, was nominated for an Academy Award, and the last, Black Harvest, had “extraordinary historical resonance,” the New York Times wrote, “so rich that watching it feels like taking an inspired crash course in economics and cultural anthropology.” Newsweek said it had “the scale and richness of classical tragedy.”

Central Highlands of Papua New Guinea

The Central Highlands of Papua New Guinea is a mountainous region forming the eastern part of the larger New Guinea Highlands. Known for its fertile valleys, diverse cultures, and significant peaks like Mount Wilhelm, the Central have been a center for human settlement for thousands of years, evidenced by a rich archaeological record. They continue to be the "heart" of the country, a place of great cultural and economic importance. [Source: Google AI]

The Central Highlands region is characterized by rugged terrain, including mountain ranges, deep river valleys, and basins with rich volcanic soils. The region includes a chain of mountains that rise to over 4,000 meters. fertile river valleys and enclosed basins are ideal for agriculture. The climate is generally tropical but varies significantly with altitude. Higher elevations experience colder conditions, with common night frosts, while lower areas are warmer. Snowfall can occur in the highest parts of the mainland.

Describing what is like to drive in the New Guinea Central Highlands, Sean Flynn wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “The road out of Mount Hagen deteriorates by the mile, the pitted blacktop of the little city crumbling to dirt before collapsing into reddish ruts scraped through the deep green of Papua New Guinea’s highlands. In the final stretch before Kilima, a bedraggled coffee plantation in the Nebilyer Valley, our Toyota Land Cruiser has to crawl in low gear, wobbling and tottering through craters and washouts...“The road tumbles down a final derelict hill and flattens into a dirt plain between a rusted-out shed, which is old, and an iron-roofed fundamentalist church, which is new. Then it narrows and rises again toward Joe’s house, up on the next hill. There are five people walking along the road between the shed and the church. [Source: Sean Flynn, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

Highland Tribe Society and Customs

Many Highland societies and tribes are organized around clans which live in distinct settlements. Clans are divided into sub-clans which are essentially large extended families with a founding ancestor that can often be traced back to a male heir living five or six generations ago. Marriages are between members of different sub clans and the children become members of the father's clan.

Highland men who wear traditional costumes wear a belt with bunches of leaves passing over the rear called "arse grass." Cassowary quills, shells and ballpoint pens are all placed in the round hole through the nasal septum. [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perennial Press, Harper and Row]

Many Highlanders traditionally cooked their food inside banana leaves placed on rocks heated by hot coals. A Highlander wedding is as much a sharing of wealth as it is a union of two people in love. The groom pays the bride's family something like 12 pigs, 30 pearl shells and US$4000 in Papua currency. Highland men love to show of their arrow scars and tell stories about how they got them.

In the Mt. Hagen area women, who usually have clean, well-oiled bodies, cover themselves with mud to symbolize death and decay. They cover their head with strands of gray grass seeds called Job’s tears and wear dozens of necklaces that are removed one day at a time until the mourning period, which can last for months, is over.

Minj women from the Wahgi Valley wear traditional bridewealth costumes made of fine feathers and body paint. They present themselves like this along with bridewealth items such as shells and pigs which are received by her future husband’s family. The costume is meant to highlight her beauty, good health and vitality and indicates the wealth of her family.

Some of the hunter-gather tribes in the highlands use hornbill bills for spoons and fill a string bag of wood fiber with hawk feathers to keep dry on hunting expeditions. Lianas are pulled back and forth over a stick to start a fire and houses are built on top of stilts for defense. [Source: "Tropical rain Forests: Nature's Dwindling Treasure" by Peter White, January 1983]

Highland Tribal Wars

Mainly through the efforts of the Australian field officer, or kiaps, who governed the remote regions of PNG before independence, cannibalism and headhunting were brought under control in the highlands. Although headhunting is no longer practiced there has been a resurgence of tribal warfare which is mainly confined to intra-clan revenge killings.

Sean Flynn wrote in Smithsonian magazine: ““Tribal wars in the highlands were almost theatrical affairs, with battles scheduled for specific times and places — say, a field burned and stomped clear of grass so nobody could stage ambushes — and fought primarily with spears and arrows, big wooden shields and the occasional homemade shotgun.... There were dozens of casualties. At one point, Joseph Madang, was outflanked, shot by one of those primitive guns, chopped with steel axes, killed. [Source: Sean Flynn, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

As one tribesman said, “The only reason that we killed people was simply that if we hadn’t have killed them, they would have killed us and all our carriers, all the people that were with us. The gold had nothing to do with it.” [Source: Sean Flynn, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

White Men in The Highlands

Sean Flynn wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “Long after missionaries and Europeans settled on the coast of New Guinea in the 19th century, the mountainous interior remained unexplored. As recently as the 1920s, outsiders believed the mountains, which run the length of the island from east to west, were too steep and rugged for anyone to live there. But when gold was discovered 40 miles inland, prospectors went north across the Coral Sea to seek their fortunes. Among them were three brothers from Queensland, Australia: Michael, James and Daniel Leahy, the children of Irish immigrants, who in the early 1930s hiked to the top of the ridges with a group of native porters and gun bois (or armed guards) from the coast. [Source: Sean Flynn, Smithsonian magazine, March 2018]

“In the highlands the Leahys found wide, fertile valleys, groomed with garden plots that were later estimated to feed a million inhabitants sorted into hundreds of tribes and clans. The highlanders lived in huts of timber and kunai grass, used stone tools and fought with wooden spears and arrows. Just as white settlers had been unaware of their existence, the highlanders had no idea that anyone lived beyond the mountains.

“At first, they suspected the white men were spirits, or maybe lightning come to earth. More curious than afraid, they traded with the white men, sweet potatoes and pigs and women in exchange for steel axes and shells (plentiful on the coast, but rare and highly prized in the highlands). When the expedition encountered new tribes, Michael “Mick” Leahy, the oldest brother and acknowledged leader, would shoot a pig to demonstrate his superior firepower. If a tribal “big man” tried to rally his warriors into a raiding party, Mick and his gun bois would shoot a few of them, too.

“The Leahys traipsed through the highlands until, in 1933, they struck a claim near what is now Mount Hagen. There they built an airstrip, with friendly locals stamping the dirt flat in endless sing-sings, and settled in to make a modest fortune dredging shiny rocks from the streams. In time, the Leahys became famous for “opening” the interior to the outside world, and Mount Hagen grew into one of the country’s largest cities.

Highland Gatherings and Sing Sings

As many as 100,000 Highlanders show up for the annual Highlands Gathering in Mt. Hagen. Thousands of these wear traditional brightly colored costumes. The famous Asaro mud people are there. Women are also there who paint their faces with pig grease in the pattern of the tree python...as well as men with kangaroo tail bibs and 12 inch shells stuck through their noses. For entertainment "chorus lines of warriors" dressed in birds of paradise plumes perform the "Shhhh" dance with drums and spears. Ironically enough, the festival was conceived by Australian administrators to teach the highlanders the latest in agricultural methods.

Highland gatherings grew out of moka, originally a gathering or enemies to make peace and decide reparations. They are now competitions of the most ornate warriors, although violence on occasion has broken out. Moka was a highly ritualized system of exchange in the Mount Hagen through which reciprocal gifts of pigs helped tribesmen achieve status and settle disputes. They became illustrations of the anthropological concepts of "gift economy" and of "Big man" political system. Anthropologist Nancy Sullivan, who worked in the Highlands, told National Geographic, "Here men are the objects of beauty. To be masculine is to be well made-up. Women, though, court danger are too attractive. Men are already afraid of the power of women's biology."

Sing Sings, another group of occasions for tribal display, were organized after World War II by colonial government officials to promote regional peace among all the participating tribal clans. Dance and costumes express a great degree of individuality and innovation. In the 1980s dancers painted themselves with white stripes and wore long pointy bamboo fingers in costumes inspired by zebras.

Highlands Treehouse Sorcerers

Sorcery in this part of the Highlands is an ancient practice deeply interwoven with local traditions. Sorcerers, often viewed as both shamans and spiritual mediators, are believed to wield powers that can heal or harm. Nestled near Kundiawa, the small village of Gumbo lies hidden within a dense bamboo forest. It is home to the Kamunyombglo clan of the Narku tribe — and to one of the region’s most intriguing figures: a sorcerer and his aged father, who live in a secluded treehouse near the village entrance. The young sorcerer, now in his early thirties, continues the lineage of his father, embodying the enduring role of the sorcerer in village life. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

Clad in simple loincloths and adorned with long strands of green moss woven through their hair, the two men claim that the moss eventually fuses with their skin — a symbol of their profound connection to nature. Despite efforts by Christian missionaries to suppress such practices, the villagers still turn to the sorcerers for guidance: to explain misfortunes, lift curses, and counteract spells. Their role is hereditary, and their position comes with restrictions — they are forbidden to marry or engage in intimate relationships.

When traditional “bush doctors” fail to cure illness, the people of Gumbo still trust the sorcerer’s healing rituals. These rites involve the use of plants, oils, smoke, and sacred incantations intended to banish malevolent spirits and restore balance. Beyond healing, sorcerers also serve as arbiters of justice. In cases of theft or wrongdoing, black magic is used to identify the culprit. Punishments can be severe — such as flogging with a poisonous leafy birch that inflicts painful burns and rashes. In extreme cases, the sorcerer may even administer fatal retribution, though the precise methods remain secret.

Gumbo Treehouse Sorcerers Tribes of Papua New Guinea

The sorcerer and his father live in isolation, rarely descending from their elevated dwelling. The father, who once shot a man with his bow and arrow, now remains confined to the treehouse, unable to move freely due to his age and frailty. With dwindling access to wild game, their diet consists largely of forest fruits, nuts, bush rats, insects, snakes, and small reptiles — all roasted over a fire in their lofty home. The prized tree-kangaroo, or kaskas, is considered a delicacy and, at times, eaten raw.

Before the arrival of Christian missionaries, the many tribes believed that the spirits of the forests and rivers governed their well-being and daily sustenance. They communicated with these spirits through rituals and sacrifices, offering animal blood on sacred sites to seek blessings, strength in battle, or prosperity in times of need. While Christianity has largely replaced these animistic beliefs, many traditional practices remain cherished as expressions of identity and continuity—bridging the tribe’s ancestral past with its present-day faith.

Bilas — Highland Body Painting

Ceremonial dressing, or bilas, holds a central place in the cultural expression of the Enguwal Tribe of the Tambul-Nebilyer District in Papua New Guinea’s Western Highlands Province. More than mere decoration, bilas embodies identity, pride, and a deep connection to nature and ancestral tradition. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

The intricate designs of bilas are inspired by the natural environment. Colors are traditionally made from soil, clay, charcoal, and pig fat—each hue symbolizing life’s essential elements: earth, trees, water, sun, and air. Materials used in crafting these attires are diverse, including bamboo, bark cloth, animal skins, beads, feathers, and even strands of human hair. Over time, the tools and materials have evolved—modern knives now replace bone or bamboo implements, artificial beads have supplanted bush beads, and store-bought paints are sometimes used for face decorations. Yet, the meaning of bilas endures as a symbol of belonging and reverence for cultural heritage.

Within the Enguwal community, the Komb clan of the Gaim subclan holds particular prominence in preserving these traditions. The origins of their ceremonial dress and dance are rooted in an ancestral legend known as “The Kuru Ware Story.” According to this tale, a man named Gale dreamed of a tree kangaroo that sang a sacred chant called Kuru-Ware, revealing to him the patterns of the tribe’s attire and dance. Upon waking, Gale shared his vision, and from that dream the tribe’s ceremonial costume and dance were born—a heritage that continues to be performed today to honor their ancestors and the spiritual world.

Bilas is worn not only during grand ceremonies but also for life’s significant moments—marriages, funerals, warfare, births, and celebrations of good health. Each costume carries distinct meaning, reflecting the tribe’s values and the cycle of life.

Highlands Groups Modern Life and Tourism

Edie Bakker worries about what will happen to the Bahinemo, a group in northwest Papua New Guinea. "Not just their outer culture," she says, "what they eat, what they wear — but more devastatingly their inner culture. Who they are as people, how they approach life." Because the government has trouble getting vaccines to the remote forests children still die of diseases like whooping cough. Mothers drown their sorrows by wailing and the babies are often buried in cardboard boxes. [Source: "Return to Hunstein Forest", Edie Bakker, National Geographic, February 1994]

The Bahinemo consider tourism to be evil. "Tourists bring beer," said one village head man, "We have enough problems with alcohol as it is. It has made our teenagers stop listening to us and is tearing up the families. The last thing we need is a steady stream of beer."They also find dancing for tourist groups to be demeaning. When Bakker asked a dancer what he was chanting, he said, "They are telling the spirits, "We shouldn't do be doing this. We shouldn't be doing this. We only do it for the tourists, to make a lot of money.'"

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025