Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups / Arts, Culture, Sports

HIGHLANDS ART FROM NEW GUINEA

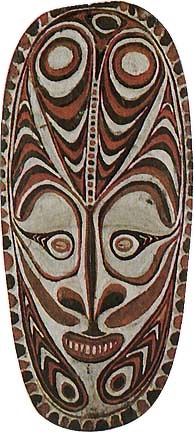

Kapriman mask

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The peoples of the New Guinea Highlands primarily confine their artistic output to elaborate forms of personal ornamentation. Sculpture among Highland peoples is rare. In some areas of the Eastern Highlands, however, artists produced thin carved boards of various types, often in openwork and always painted with highly stylized designs. These were displayed in great numbers at large-scale ceremonies during which quantities of pigs were sacrificed to feed ancestral spirits and promote fertility.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Although a widespread tradition of stone carving flourished in the New Guinea Highlands in ancient times, sculpture among contemporary Highlands peoples is rare. The brightly painted ceremonial boards known as gerua are a notable exception. Produced by a number of Highlands groups, gerua are made in several different forms. The largest and most important are the wenena gerua (human gerua), stylized human figures adorned with colorful geometric designs. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007; Eric Kjellgren is a leading scholar of the arts of Oceania. Formerly curator of Oceanic Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and director of the American Museum of Asmat Art (AMAA) and Clinical Faculty in Art History at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, he has worked extensively with contemporary Indigenous Australian artists and done field research in Vanuatu]

Gerua art works from the Siane people form the centerpieces for dances at their Pig Feast, a ceremony performed by each clan once every three years. The feast honors the korova, ancestral spirits who are invited into the community to witness the dances, hear the playing of sacred flutes, supervise initiation rites, and partake in a ceremonial meal of pork. The climax of the rites is the dancing of the gerua, in which some two hundred dancers carry the brightly painted boards, surrounded by as many as two thous and spectators.

Anthropomorphic boards embody symbols of the sun (the round head) and moon (the diamond-shaped body). In this example one can trace an ambiguous image, which can be seen either as a figure with hands touching the head and the legs drawn up, or as a standing figure. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is home to wood and paint Canoe Prow made by Iwam people in Aumi village in the Upper Sepik region. Dating to the early to mid-20th century, it is 4.12 inches high, with a width of 1.62 inches and a depth of 23.5 inches (10.5 x 4.1 x 59.7 centimeters).

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Oldest Sculptures in New Guinea

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The earliest known works of Pacific sculpture are a series of ancient stone objects unearthed in various locations on the island of New Guinea. Enigmatic remnants of a vanished culture, or cultures, that once fiourished widely on the island, they are found primarily in the mountainous Highlands of the interior.' Thus far, no examples have been excavated in a secure archaeological context, and their precise dates remain unknown. However, organic material trapped within a crack in one example has recently been dated to about 1500 B.C., indicating that at least some of the images are of great antiquity. These stone 14 sculptures fall into several categories, including independent figures, mortars, pestles, club heads, disks, and other forms. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The tops of many pestles are adorned with images of human heads, birds, or birds' heads. The mortars display similar anthropomorphic and avian imagery as well as geometric motifs. Freestanding figures include images of humans, birds, phallic forms, and long-nosed animals that some scholars suggest represent ech id nas (spiny egglayi ng mammals resembling hedgehogs). The original significance and function of these stone objects are unknown.

However, it seems reasonable to speculate that they were created for use in ritual contexts and that the human and animal images that adorn them represent ancestors, spirits, and totemic species. Reportedly found in the Morobe district, the stone bird head seen here likely represents the head of a cassowary, an ostrich like bird that lives throughout the island. Among many contemporary New Guinea peoples, the cassowary is regarded as a supernaturally powerful animal, and its appearance here suggests that such beliefs extend far into prehistory. This image may originally have been the finial of a pestle, from which it was later broken.

The lower end, however, is ground smooth, indicating, alternatively, that it may have been created as an independent image. If so, it might have served as an ornamental flute stopper-the lower end would have been inserted to plug the upper end of a ceremonial bamboo fiute-similar to the wood fiute stoppers created by the latmul, Biwat, and other contemporary peoples in the Sepik region. Unearthed in the Mount Hagen region of the Western Highlands, the complete bird figure is rendered in smooth, minimalistic lines that st and in contrast to the finely detailed features of the smaller bird head. Too large to have served as a pestle finial or flute stopper, it was likely an independent image.

Ceremonial Stones in New Guinea

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Although nothing is known of their original use, prehistoric stone objects play, or played, important roles in the religious and ceremonial life of many contemporary Highlands peoples. Unearthed by chance in gardens and, more recently, road construction, or rooted up by foraging pigs, unusual stones, whether ancient artifacts or natural objects like fossils, are regarded as supernaturally powerful. Some are said to be the manifestations of spirits, who sometimes reveal the location or use of the stone to the finder in dreams. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

After finding one such stone, a man of the Fore people recounted being visited by its spirit, in the form of an old man, who told him: "I underst and how to look after gardens and pigs, I can make big crops come up: these I can eat too [i.e., consume their spiritual substance]. You have dug me up. Look well upon my body and carry me to your house: there I can stop with you, and you will have plenty of pigs." As this account indicates, the stones were often associated with fertility.10 Treated in the proper ritual manner and anointed with red ocher and pig fat, some stone objects had the power to ensure bountiful harvests, healthy children, and large herds of pigs. Others were employed in curing sickness, bringing luck, and fending off malevolent magic or as potent war charms that ensured the accuracy of the owner's bow or deflecting the arrows of his enemies.

Until recently, the Melpa, Kyaka Enga, and some other Highlands peoples would occasionally gather substantial numbers of sacred stones together for a dramatic cycle of fertility rites, known as amb kor or kor nganap. Involving the construction of extensive ceremonial grounds and requiring the sacrifice of hundreds of pigs, the full cycle required years to complete.

Performed by men, the rites were devoted to a potent female spirit. The sacred stones were amassed in specially constructed ceremonial houses, which served as an inner sanctum. Laid out on beds of freshly gathered fern fronds and anointed with red ocher and pig fat, the stones were said to contain the power of the female spirit and were the focus of dancing and ceremonial feasts held in her honor. At the conclusion of each stage in the cycle, the stones were buried. The correct performance of the rites renewed the fertility of the earth and brought vitality and prosperity to the community.'

Wenena Gerua (Ritual Board) from the Eastern Highlands

Wenena gerua (Ritual Board) is a wood sculpture made of wood, paint, feathers and fiber by the Siane people of the Eastern Highlands. Dating to around 1950, one example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is 55.12 inches high, with a width of 15 inches and a depth of 1.5 inches (140 x 38.1 x 3.8 centimeters). [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Eric Kjellgren wrote This work, like many wenena gerua, is decorated in a combination of indigenous pigments and trade paint. Standing in brilliant contrast to the muted browns and greens of the surrounding landscape, the vivid colors of wenena gerua would have been striking-all the more so when carried on the heads of hundreds of moving dancers.

Smaller types of gerua are held in the arms, but the large wenena gerua are worn as headdresses: the U-shaped base is fitted over the head of the wearer, who uses the leglike projections as handles to hold the board in place." The wenena gerua is supernaturally activated by placing a crown of human hair, a material imbued with the power of the spirits, on the head of the stylized figure. The dance takes place over two consecutive days, timed so that the final hours of the performance are illuminated by the light of the full moon. ~ The ceremony concludes with the sacrifice and consumption of large numbers of pigs, after which the korova, having been lavishly fed and entertained, depart. The gerua boards are said to capture the spirits (auna) of the slaughtered pigs, returning them to the korova, who ensure the continuing renewal and vigor of the clan 's pig herds.

The imagery of wenena gerua is complex. The spare human forms are ambiguous, and it is possible to read them either as seated figures with the knees bent and the legs drawn into the body or as standing figures whose legs are formed by the straight handles at the base. Each of the geometric elements that combine to form the human figure has a separate name and meaning. The round disk that forms the head is called for numuna (house of the sun), whereas the diamond-shaped body is referred to as afanik1 (h and of the moon) and the V-shaped motifs that form the limbs are termed oma, meaning "road " or "way." The brightly colored geometric patterns that cover the surface also have significance. Each gerua is adorned with a specific pattern of designs that belong exclusively to the clan who creates it. Although purely geometric, the designs symbolize the clan 's ancestors, though the overall figure reportedly depicts a nonancestral supernatural being.

Kwoma and Nukuma Ceramic Art

The Kwoma and Nukuma are closely related peoples living in and around the Washkuk Hills north of the middle Sepik River in northern New Guinea. Among them ceramic artists are especially revered. It is the names of accomplished potters, more than those of any other type of artist, that are preserved and passed down in local oral histories. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

To become a master potter requires not only an intimate knowledge of the material but also the ability to recall and flawlessly execute some forty to eighty different motifs, which must be precisely laid out and carved into the unforgiving surface of the moist clay. Potters in these groups do not rewet the clay when working, and considerable speed and dexterity are required to complete and decorate the pot before the medium dries out. A variety of vessels, which serve both mundane and ritual functions, are produced. Although women are responsible for producing most of the functional varieties, ceremonial ceramics are made by men.

Perhaps the most remarkable of these are the unique head-shaped pots created for use in ceremonies surrounding the growth and harvest of yams. The bodies of the vessels are built up using the coiling technique to produce a potlike form, to which the facial features are applied and modeled freehand. Like the larger wood heads (yena), head pots are displayed during an annual cycle of rituals celebrating the yam harvest. One Nukuma origin tradition asserts that the ceramic effigies represent the original form of these sacred head images and that the wood versions were later copied from them. Both the ceramic and the wood heads depict sikilowas, powerful spirits associated with the village clans and events during the primordial creation period.

In one Nukuma yam ceremony, the ceramic heads are arranged around the base of a large container holding the ceremonial yams; the heads face inward, toward the center, where a larger wood head is erected. All the heads are either male or female, according to the gender of the spirit they portray. Heads and yams are closely associated metaphorically in Kwoma and Nukuma religion, and the shape of the head pots may evoke the form of yam tubers.

Yena (Head for Yam Ceremony)

The Kwoma, Nukuma, and Yessan-Mayo share a unique art tradition associated with a religious cult centered on the cultivation of yams. A sequence of three rituals, called "yena," "minja," and "nokwi," each involving a different type of figure, is performed in honor of the yam harvest.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: A ceremonial as well as a staple food, yams are planted only by senior initiated men. Endowed with supernatural properties, the tubers cannot be eaten until the spirits (sikilowas) responsible for their growth and, more generally, for the welfare of the community have been appropriately honored. Following the yam harvest, the sikilowas are ideally celebrated in a sequence of three ceremonies, yena ma, mindja ma, and noukwi, each of which involves the construction of an elaborate ceremonial display of yams, accompanied by a specific type of figure. The first of the rites, yena ma, centers on the yena, stylized oval heads set on long necklike stalks. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The yena head, with its strongly protruding brow and long, pendulous nose, comes from the Yaysin-Mayo region and retains its bright polychrome paint, which was renewed each time the image was used. During the yen a ceremony, a group of yena heads, each portraying an individual, named spirit, is mounted atop the kobo, a large, basketlike structure containing a portion of the yam crop. Lavishly decorated in beards and hair made from white chicken feathers, cassowaryfeather capes, and a diversity of other ornaments, as many as twenty yena images may appear in a single ceremony. Each belongs to a specific clan and is either male or female, depending on the specific spirit it portrays. The second ceremony, mindja ma, involves the display of a different type of image, the mindja, in which the head, resembling that of the yena carvings, appears with a long, slablike body, from which a series of archlike forms emerge.

During the rites a single pair of mindja images, representing two male sikilowas, is displayed on a koho similar to that constructed for the yena heads. The mindja portray powerful water spirits who live in lakes and whose forms can sometimes be glimpsed just below the surface of the water but who are also associated with the sky. The bodies of the mindja, as in the Nukuma example seen here, are adorned with triangular motifs, which enclose a series of white diamond-shaped forms representing banana leaves (yerapuk). The undulating forms that emerge from the center depict the coils of a snake (yerakwant). Combining elements of humans, reptiles, and plants into a single image, the form of the mindja images masterfully embodies the otherworldly qualities of the powerful supernatural beings they portray. Open only to the most senior initiated men, the third and final ceremony, noukwi, involves the display of stylized female figures.

A Yena ceremony display was photographed at Bangwis village, December 1971. Lavishly adorned with ornaments, the yena heads are erected within a basketlike structure, which contains the ceremonial yams. The painted ceiling of the men's house is visible above.

Types of Yena

One Yena (Head for Yam Ceremony) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made by the Yasyin-Mayo people in Yau village, Washkuk Hills in the upper Sepik region. Dated to the 19th-early 20th century and made of wood and paint, it is 42 inches (106.7 centimeters) tall, with a width of 9 inches and a depth of 7 inches (106.7 x 22.9 x 17.8 centimeters). The museum also is home to a Figure for Yam Ceremony (Mindja or amarki) from the Washkuk Hills in the upper Sepik region, probably made by the Nukuma people. Dated to the 19th-early 20th century it is made of wood and paint and is 53.14 inches (135.3 centimeters) tall.

Carved wooden heads such as this one are created for yena, the first of these harvest rituals. With bulging eyes and pendulous noses, yena heads represent ancient and powerful spirits. During the ritual, village men assemble a pile of yams within the ceremonial house. The sticklike bases of the yena are inserted into the yam pile and the heads are decorated with brightly colored leaves, feathers, and other ornaments. The men then dance and sing to honor the yena spirits. At the conclusion of the ritual, the display is dismantled, the heads stored away, and preparations for the next ritual begun.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection also contains a Head for Yam Ceremony (Yena or Was Au) made of ceramic and paint, at the Workshop of Artists of Mariwai Village in the Washkuk Hills in the Upper Sepik River region by the artist Kwanggi of Kalaba clan of the Kwoma people in 1973. It is 16.5 inches high, with a width of 9 inches (41.9 x 22.9 centimeters). A similar one made in the same time and place by the same artist is 15.37 inches high, with a width of 7.75 inches (39.1 × 19.7 centimeters). Another is 15.37 inches high, with a width of 7.62 inches (39.1 x 19.4 centimeters). Yet another made of earthenware and paint from Tongwindjam village in the Washkuk Hills dates to the 19th-early 20th century. It is 15 inches (39.4 centimeters) tall.

Ceremonial House Ceiling Paintings

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Throughout New Guinea, men’s ceremonial houses were, and in many places still are, the primary focus for painting and sculpture. Like the cathedrals of medieval Europe, they are generally the largest and most sacred buildings in the village, rising high above the ordinary dwellings that surround them. Typically, entry into the ceremonial house is restricted to initiated men, although in some cases, women and children can enter under certain circumstances for specific events. Ceremonial houses serve as the venue for nearly all important male religious rites — such as initiation rites for young boys and at other times function as meeting houses or informal gathering places. Their structure and the way they are decorated can take on many different local forms and styles. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Among the Kwoma people of the Washkuk Hills ceremonial houses have no walls; instead, they consist of a huge steeply pitched roof, which extends nearly to the ground and is supported by a series of massive posts and beams. These structures have no walls and the sides are left open except when rituals are held inside. A finial, carved with images of mythical beings, projects from each gable. Some Kwoma ceremonial houses are unadorned. However, the construction of lavishly decorated examples is a source of pride for the village and its clans. The ceilings of the most ornate ceremonial houses are decorated with hundreds of brilliantly colored paintings and elaborately sculpted posts and rafters.

Paintings are made on sheets of bark or sago petioles, the bark-like bases of the leaves of the sago palm tree, which are trimmed and flattened to create a flat roughly rectangular surface that tapers slightly according to the natural form of the petiole. After a curing process, the artist covers the smooth side of the sheet with a wash of black clay. The main outlines of the design are laid out in clear water, retraced in paint, and then filled in with color. Although one man lays out the design, an assistant may perform the work of infilling and painting the bordering dots. Each painting represents a specific animal, plant, object, supernatural being, or other phenomenon associated with one of the village clans, such as fruit bats or shooting stars, for example. The manner in which these clan symbols are depicted varies greatly. Some of the more figurative imagery, such as a relatively naturalistic crocodile, typically do not depict ordinary creatures but rather represent supernatural beings who either are otherworldly animals or have assumed animal form. Many of the paintings employ abstract and geometric designs derived from features of the various animals, plants, and other subjects they portray. Paintings may also include images of natural objects such as the moon in its various phases or legendary figures from the clan’s oral traditions. While there is a fairly well-defined repertoire of specific geometric design types, the meaning of each design can vary according to the intention and clan affiliation of the artist.

When completed, the paintings are tied to the rafters on the underside of the ceiling with lengths of split cane. The panels are arranged lengthwise along the axis of the house, with a few rows placed laterally at its midpoint. The midpoint forms not only the center of the structure--the most ritually important area--but also roughly indicates the sectors allotted to each clan. In general however, there is no prescribed arrangement. Instead the works form a stunning visual patchwork of clan symbols, evoking the strength, unity, and identity of the village clans, whose members gather on the earthen floor beneath them to perform religious rites or initiation ceremonies, hold meetings, or casually socialize.

Paintings from Ceremonial House Ceilings

Painting from a Ceremonial House Ceiling

Tagopai, Workshop of Artists of Mariwai Village Papua New Guinea, 1973

A spectacular installation of Kwoma Ceremonial House Ceiling paintings in the Metropolitan Museum is 80.4 feet (24.5 meters) end-to-end, and is the largest contemporary art installation in the museum. Dating to the 1970-1973, it was made Mariwai village in the Washkuk Hills, Upper Sepik River by the Kwoma people from Sago palm spathe, paint, wood and is 30.5 feet wide and 80.4 feet (9.3 × 24.51 meters) long.

One painting from a Ceremonial House Ceiling in Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made by the artist Mburrnggei in the Amachi-Kalaba clan of the Kwoma, People in the Workshop of Artists of Mariwai Village in the Upper Sepik River region of Papua New Guinea. Produced in 1973, it made from a Sago palm spathe and paint and is 43.75 inches high, with a width of 18 inches (111.1 x 45.7 centimeters)

Another Painting from a Ceremonial House Ceiling was made the artist Yindaka of the Sunggwei Wanyi clan of Kwoma People at the Workshop of Artists of Mariwai Village in the Upper Sepik River. Produced in 1973, it was made from a Sago palm petiole and paint and is 60.5 inches high, with a width of 29.75 inches (153.7 x 75.6 centimeters)

Another Painting from a Ceremonial House Ceiling was made the artist Mundik from the Kalaba clan of Kwoma People at the Workshop of Artists of Mariwai Village in the Upper Sepik River region. Produced in 1973, it is made of Sago palm spathe and paint and is 47 inches high, with a width of 24.5 inches (119.4 x 62.2 centimeters).

Yet another Painting from a Ceremonial House Ceiling was made the artist Kulumb of the Simberaga Wanyi clan of Kwoma People at the Workshop of Artists of Mariwai Village. Produced in 1973, it is made of Sago palm spathe and paint and is 63 inches high, with a width of 17 inches (160 x 43.2 centimeters)

Bahinemo Hook Figures (Gra or Garra)

Bahinemo Hook Figure, From Art Blackburn

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Although they had permanent villages, the Bahinemo and neighboring peoples living in and around the Hunstein Mountains, south of the middle Sepik River, formerly had a semi nomadic way of life. Often deserting their settle ment for months to hunt or to extract sago from distant groves, they returned to the community for both mundane and ceremonial activities. As in other Sepik societies, the focus of ritual life was the men's ceremonial house, where male initiation and other rites took place and where wood images and other sacred objects, known collectively as gra or garra, were housed, so as to conceal them from women and children. Stylistically, Bahinemo wood sculpture forms part of the broader "opposed-hook" tradition in Sepik art, which appears most prominently among the Yimam people, who live just to the east. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Bahinemo artists created two distinct types of hook figures: flat, masklike panels with stylized human faces bracketed by small hook-shaped forms and tall, slender images, intended to be seen in profile, consisting of a series of large concentric hooks surrounding a central triangular or oval projection. Both types have a hole drilled through the upper portion, which was used to suspend the images from the rafters of the men's house. Each type of figure is associated, broadly speaking, with a different category of spirits. The flat, masklike gra are associated with forest spirits and male elders, and the hooks are typically interpreted as hornbills' beaks. The Bahinemo identify the slender hooklike images as water spirits that should ideally be immersed in swamps or other watery places.

Interpretations of their imagery vary. The images as a whole are sometimes identified as stylized catfish, with the hooks representing their numerous curling whiskers. In other instances, the hooks are said to depid the heads of horn bills and the central motif is identified variously as the sun, the moon, or the eye of a pig or cassowary. Although all gra figures fall into these two broad categories, each portrays a specific spirit whose name and powers were intimately known to the individual man who owned it. Like Yi ma m hook images, gra formerly served as "hunting helpers": their powers assisted the Bahinemo in the capture of prized quarry such as wild pigs and cassowaries. They were also reportedly used in warfare.Up to the late 1960s the images appear to have played a prominent role in male initiation. In a ceremony recorded in Wagu village, young initiates and their sponsors gathered to dance in front of the men's house, from which two men, one carrying a masklike gra and the other a hook-shaped one, emerged.

Crouching down and holding the images between their legs, the two men joined the assembled performers, hopping side by side as they danced. At the conclusion of the dance the men sat on their heels while the initiates and their sponsors stripped the masks of their ornaments. The man with the masklike gra then stood facing the ceremonial house, holding the image faceup between his legs while the initiates ate ginger hanging from its eyes and mouth. The assembled multitude then entered the men's house, where a further series of dances involving the two images took place.

One example of a Bahinemo Hook Figure (Gra or Garra) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made in the Namu village in the Hunstein Mountains in the Sepik region, Dated to the people Late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of wood and paint and 31.5 inches (80 centimeters) tall. Another from Nigiru village in the Hunstein Mountains is 46.25 '4 inches (1.2 meters) tall. A photograph of hook figures in use during an initiation at Wagu village in 1967 show a dancer clad in an elaborate costume of leaves emerging from the men's house, holds a hook-shaped gra between his legs as he performs among the initiates and their sponsors.

Telefolmin Door Boards

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The Telefolmin are one of a number of Highlands peoples, collectively called the Mountain Ok, who inhabit the rugged Star Mountains, which lie at the source of the Sepik River, known locally as the Tekin. Although Mountain Ok artists produce no figurative sculpture, they have a wel1-developed tradition of architectural carvings that adorn, or adorned, the facades of both dwellings and ce remonial houses. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In Mountain Ok villages the sexes live apart: men 's dwellings (tenumam) are situated at the highest, or "upstream," end of the village, and separate dwellings (unagam) housing the women and children are clustered around the dancing ground at the village center. Most villages also had ceremonial houses, which served for the storage and display of ancestral relics and sacred objects, although these could in some cases be kept in ordinary houses as well. In Telefolmin villages the entrances to all three types of structures were frequently decorated with amitung, brightly painted ornamental door boards adorned with geometric designs centered above a large hole through which the occupants entered and left. In some instances, the amitung was flanked by additional ornamental house boards that covered some or all of the front facade.

According to oral tradition, the art of carving door boards and other objects was given to humanity by the sun, which cast down the design for the first amitung so I from the sky as a prototype for later artists to follow. Although a door board might be produced by one of the household residents, the amitung were often commissioned from skilled carvers whose artistic abilities were well recognized in the community. If the carver was not a close relative, he was paid for his services by the commissioners, who provided him with food during the carving process as well as a final gift of pork.

The amitung were carved from broad planks cut from large softwood trees. After the plank had been roughly shaped and dried, the artist marked out the design in charcoal. The surrounding areas were then cut away, leaving the design elements in low relief. These raised designs, as here, were always decorated with a deep black paint made from (or metaphorically associated with) the soot that accumulated on the underside of the roofs of men 's houses, which symbolized male religious and social solidarity and aggression. The white, red, and, occasionally, yellow pigments that adorned the recessed areas were applied according to the individual taste of the artist.' Although carved from softwood, amitung were surprisingly durable and were often kept and reused over several generations. Originally carved by an artist named Abanfogop about 1910, this amitung was subsequently inherited by his relative Kulibipnok and remained in use nearly sixty years later." According to Telefolmin artists interviewed in the early 1960s, the designs on the amitung are purely decorative and have no overall meaning.

Shields (Wörrumbi) of the Mendi culture; Southern Highlands Province, Bowers Museum

However, they also stated that many of the individual design elements do have a specific significance.' The design typically centers, as here, on a lozenge-shaped or circular form, which depicts a central element in the body of a human or animal, such as the heart, navel, solar plexus, female reproductive organs, or abdomen. In the present work this central element has triangular projections on either side, possibly representing the wings of the flying fox, a large species of fruit bat. Th e curling spiral projections that emanate from the central motif are identified as the limbs of humans, spiders, crocodiles, or lizards, and the spiral motifs that appear near the top of the board are identified as the eyes of humans, birds, or lizards.' Viewing these elements in combination has led some Western researchers to suggest that as a whole the design on the door board resembles a highly stylized human figure, perhaps symbolic of the power of the ancestors whose sacred relics were often preserved inside the structures the boards adorned.

One example at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was carved by Abanfogop in the early 20th century in Telefolip village in the Star Mountains in the upper Sepik region. Made from wood and paint it is 9 feet 6 inches (2.9 meters) high. A 1964 photograph of a Tifalmin cult house (yowolamem) at Bulolengabip village, Ilam Valley, shows the entrance hole in the central door board which has been sealed with sheets of bark. On either side are brightly painted house boards, which adorn the remainder of the facade.

Highland Shields (Tiye)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The territory of the Sanio people encompasses portions of the Wogumush, Leonhard Schultze, and April rivers, whose waters drain northward into the upper Sepik River. Like many upper Sepik peoples, the Sanio produce relatively little wood carving in comparison with middle and lower Sepik groups. The most imposing Sanio works are their intricately decorated shields, known as tiye. There is some uncertainty about the precise manner in which these large war shields were employed in combat. Tiye were reportedly used by individual warriors, who carried fighting spears (ti) in their other hand to hurl at their opponents. They are also said to have been employed by specialist shield bearers, who held them up to shelter one or more bowmen, who fired from behind the protective barrier. It seems likely that tiye were used in both these fashions. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The imagery of Sanio shields often consists, as here, of a single central face, or at times of several faces arranged in a vertical row down the center, surrounded by geometric designs. In examples with multiple faces, the orientation of the individual faces is often variable, with some depicted right side up and others upside down. Carved in a tapering oval form, tiye were typically broader at the top than at the base, so it is conceivable that the present work was intended, for unknown reasons, to be viewed with the central face in an inverted position.

Strikingly minimalist in their conception, the facial features are reduced to basic geometric forms. The eyes appear as concentric circles and the nose and mouth are combined in a single arrowshaped motif. On some tiye the nose is absent, with the mouth appearing simply as a crescent. The nature and significance of these engaging faces are unknown. However, like the vast majority of human images in Sepik art, the faces are likely those of spirits, ancestors, or other primordial beings whose presence on the tiye may have afforded supernatural protection to the shield bearer.

An example of Sanio shield at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made by the Sanio people in Begapuki village in the upper Sepik region. Made in the late 19th-early 20th century from wood and paint, it is 60 inches (1.5 meters) in length.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art also houses a Subiyongim shield made of wood, fiber and paint by the Mountain Ok people. Dating to around 1870, it originates from Telefomin and Folfol Creek, Upper Sepik River, West Sepik Province, and is 62.75 inches high, with a width of 20.37 and a depth of.75 inches (159.4 x 51.7 x 1.9 centimeters)

Enga Sand Painting

Enga's sand painting art is an unusual art form in which is ground from the myriad of different coloured stones and earth found in Enga province and used make images that are mainly brown, black and gray in color. According to Enga Tourism: Enga's sand painting evolved out of the workshop at the Take Anda in the late 1970s and early 1980s and has become a contemporary art style that is distinctly Engan. Artworks, typically depict scenes of Enga's traditional life and local wildlife, particularly the birds. Portraits of well known figures are also popular. [Source: Enga Tourism]

One of the best known Enga sand painters is the sculptor Akii Tumu, who graduated from the National Art School in Port Moresby in the early 1980s. Dr. Robin Torrence of the Australia Museum wrote: He developed the time-consuming technique while he was head of the Enga Culture Centre in response to a lack of funds for buying canvas, paints and brushes. To make the sand used in the artworks, the artist grinds up coloured stones from secret source locations and sprinkles single colours of the ‘sand’ onto small glued areas on a board, and then removes the excess sand once the glue has dried. [Source: Dr Robin Torrence, Australia Museum, March 24, 2010]

Steps to make an Engan sand painting: 1) the process begins by selecting colours naturally occurring in the Earth and grinding these to a fine sand. 2) The outline of scenes and subjects are then drawn on to wooden boards before the colouring in process starts. 3) Glue is painted on the boards where sand of the colour chosen will be sprinkled by hand to the board, sticking to the glue, which dries it into place. 4) The true artistic skill comes from the experience of knowing which colours to place where, to truly bring out these natural colours, shades and contrasts.

On works by artists Lucas Kiske and Joseph Kuri at the Australia Museum, Torrence wrote: Unlike earlier versions that were more similar to traditional motifs, the recent forms of sand paintings depict vignettes of traditional Enga daily life in a realistic modern style, making them more readily accessible to Westerners. Lucas's picture shows a hunter shooting at a possum in a tree, his dog ready to pounce should the prey try to escape; Joseph's artwork portrays a courting man and woman seated, wearing full traditional finery of shells, feathers and woven cane. In both pictures the man carries the traditionally important stone axe.

Papuan Highland Body Painting and Adornment

According to the Pitt Museum at Oxford University: In the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, self-decoration is associated with festivals and ceremonies where people reinforce their identity as members of a group or clan. Particular combinations of body painting, wigs, feather headdresses, necklaces, armbands, aprons, ear and nose rings signify who you are and where you are from.

One photograph at the museum shows Wulamb, a Wahgi girl, preparing to receive her bridewealth prior to marriage. She wears a headdress of cassowary and red parrot feathers and is draped in a purple cloth to protect her clothes and ornaments from the powdery face-paint that is being applied. The face is painted, not with any particular design, but to look shiny and glossy as a sign of ancestral favour. Red, yellow and white remain favourite colours with which to paint the face and body in Papua New Guinea. Today synthetic colours are often used but bamboo tube shown in the photograph, with a plant-fibre stopper, was acquired before 1901 and contained a natural red pigment, the value of which is indicated by the time and effort taken to decorate its surface with carvings. In pre-contact New Guinea, when metal was not available, carving tools were made from local materials such as shell and splinters of basalt. Animal teeth, boars' tusks, or sharpened bird bones were often used for engraving, whilst sanding was done with actual sand or sharkskin.

According to the Australia Museum, which hosted on an exhibition on Papua New Guinea body adornment: “the practice of body adornment is known as bilas, a word from the pidgin language Tok Pisin, and celebrates the intrinsic interconnection of peoples to place and to all things living. Over millennia, different forms of bilas have emerged, fulfilling varied everyday physical, social, and spiritual needs in unique ways. Made from an array of natural resources including shells, feathers and plant fibers, some adornments signify power or prestige, others are for cultural celebrations and ceremonial purposes.

Papua New Guinea's astonishing natural environment has long provided abundant resources. It is the natural world that provides the spiritual knowledge and materials, and inspires the patterns and designs for adorning the body. Bilas is an amplification of the intimate relationship that the people of Papua New Guinea have with the natural environment. When adorned, bodies are transformed from ordinary to sublime, becoming embodiments of the living environment.

Bilas is often worn as a sign of prestige and wealth or as a symbol of leadership. It enhances self-esteem and identity. These types of adornment are created for display in public ceremonies such as weddings or as exchange items between communities. In contemporary forms of bilas, natural materials are interlaced with bits of coloured plastic, beads, bells, zippers and synthetic fibres. The charm of new materials offers opportunities for the expansion of self-expression as well as testifying to the resilience of traditional methods. In Papua New Guinea today, bilas is an evolving and adaptive practice that is constantly reformed and re-ignited from generation to generation.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, William A. Lessa (1987), Jay Dobbin (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2025