Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

MARING

The Maring are highlands group known their use of a bush fallow (swidden) agriculture, their traditional warfare and ritual pig feasts, like the kaiko. Also known as Yoadabe-Watoare, they are linguistically and culturally linked, though geographically split between the mountains of Simbai Valley (Madang Province) and the Jimi Valley (Western Highlands Province). As of the 2020s, the Christian research group Joshua Project estimated the Maring population at approximately 27,000, with most speakers found in Papua New Guinea’s Madang Province and Western Highlands District. The primary language is Maring, part of the Trans–New Guinea language family. [Source: Joshua Project; Google AI]

The Maring have been the subject of extensive ethnographic study, most famously by Roy Rappaport, whose book “Pigs for the Ancestors”, work provided deep insights into their agricultural systems and rituals. In the 1990s, the Maring were composed of twenty-one named clan clusters. Although geographically separated, linguistic, social, and cultural evidence links both Maring populations most closely to the peoples of Papua New Guinea’s western highlands. Maring territory extends for about 350 kilometers (220 miles) through the Bismarck Mountain Range. The region is heavily forested and mountainous, with a humid climate divided into relatively wetter and drier periods. The difference in rainfall between these two seasons is modest, and rain typically falls at night. Temperatures remain fairly constant throughout the year, ranging from the low 60s°F (17-18̊C) to the high 70s°F (25-26̊C). [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Maring Language — also called Mareng or Yoadabe-Watoare — belongs to the Jimi Subfamily of the Central Family of the East New Guinea Highlands Stock. It is a member of the Chimbu–Wahgi branch of the Trans–New Guinea family and includes several dialects: Central Maring, Eastern Maring, Timbunki, Tsuwenki, Karamba, and Kambegl. All speakers can understand the Central Maring dialect. According to the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS), Maring is rated Level 5, meaning it is still developing but not yet sustainable. The language is considered threatened on the Agglomerated Endangerment Status (AES) scale. Literacy among native speakers is below 5 percent, with a similar rate among those using Maring as a second language. [Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Vol. 2: Oceania,” ed. Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

History: Linguistic and other evidence suggests that the Maring migrated into their present territory from an undetermined region to the south. They long maintained trade relations with neighboring groups. Warfare followed a staged pattern, escalating from “small fights” to “true fights” fought with axes, spears, and bows and arrows. Conflict often stemmed from interpersonal disputes — such as wife stealing or debt — but was highly ritualized and regulated. Maring oral tradition includes myths of origin tracing clan descent to a group of brothers who migrated from the southwest and married local women. Each group of descendants, or Mi, honors clan heroes and ancestors through legends and speeches.

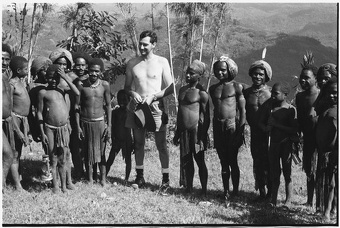

Contact with Europeans came relatively late: the first Australian patrol reached Maring territory in 1954, and full governmental control was not established until 1962. Indirect European influence was felt earlier through steel tools and new diseases such as dysentery and measles that entered regional trade networks in the 1940s. Cargo cults — introduced by groups north of Maring territory — briefly gained popularity during this period but soon faded. To facilitate administration, the Australian government appointed local representatives known as luluai (headman) and tultul (assistant headman), though these positions had little impact on local governance. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Maring Religion, Family and Kinship

According to the Joshua Project, about 95 percent of Maring people are Christian, though traditional beliefs about ancestral and nature spirits remain deeply embedded in daily and ritual life.Ancestor worship forms the core of Maring spirituality. Success in gardening, hunting, pig rearing, or warfare depends on the favor of ancestral spirits. Warriors slain in battle become rawa mugi, a special class of ancestral spirits believed to dwell in the northern part of Maring territory. Other spirits inhabit natural features of the landscape, while shamans communicate with the supernatural realm through a being known as the “smoke woman.” [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Vol. 2: Oceania”; Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Shamans and “fight-magic men” (always male) hold significant ritual authority, particularly in preparing for war. Sorcerers — often identified as wealthy men who are not sufficiently generous — are feared for their ability to cause illness or death through magic. The kaiko is the most elaborate Maring ceremony. It unfolds over a year or more, culminating in massive feasts and dances featuring elaborate body decoration — feathered headdresses, fur-trimmed waistbands, and painted faces. The final pig kaiko involves the slaughter of dozens, even hundreds, of pigs, fulfilling social debts and marking the renewal of clan alliances. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Vol. 2: Oceania”]

Marriage rules prohibit unions with a man’s mother’s clan or his own subclan, though marriages between different subclans of the same clan are permitted. Local marriages are preferred since a husband gains land rights from his wife’s kin. Sister exchange is ideal, minimizing bride-wealth payments. Marriages may begin informally with small payments and cohabitation; they become stable once children are born and full bride-wealth is paid. Polygyny is admired but uncommon due to the high cost of bride-price. The basic domestic unit includes a man, his wife, and their children, though men and women often reside in separate dwellings. Children remain with their mothers until around age eight, when boys move to the men’s house. Girls stay with their mothers until marriage, learning domestic and agricultural skills by observation.

Maring clans trace descent patrilineally to a group of mythical “fatherless brothers.” Each founding brother is regarded as the ancestor of a subclan. Kin terminology follows the Iroquois (bifurcate-merging) pattern: the father’s brothers and mother’s sisters are addressed as “father” and “mother,” while cross-sex siblings of parents are “aunt” and “uncle.” Parallel cousins (children of same-sex parental siblings) are considered siblings; cross cousins (children of opposite-sex parental siblings) are potential marriage partners. All land is collectively owned by the clan cluster and its subclans. Access to land by outsiders may be granted through historical or marital ties.

Maring Villages, Society and Economic Activity

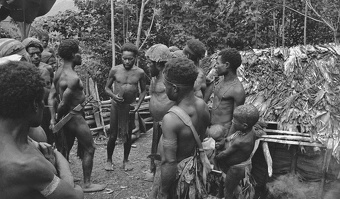

Maring settlements are described as “pulsating” — dispersed during normal times but periodically clustering around a central dance ground during major rituals. A compound typically consists of a men’s house for adult males and initiated boys, and several women’s houses located downhill, where women, young children, and pigs reside. Traditional structures are built of wooden frames with pandanus thatch. Modern homes may combine male and female spaces under one roof, though gender separation remains culturally important. Near the dance ground stands a “magic house,” serving as a communal meeting place for men.

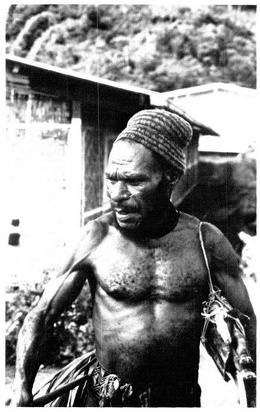

Maring men and boys discussing garden damage done by a neighboring group’s pig from Roy Rappaport Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego

The Maring are farmers, practicing a bush fallow (swidden) system of shifting cultivation. They grow sweet potatoes, taro, manioc, bananas, and greens, along with sugarcane, pandanus, and more recently, maize. Pig husbandry is central to their economy and ritual life. Male pigs are castrated to ensure size and traded to expand herds rather than bred locally. Hunting and gathering supplement subsistence, and eeling holds ritual significance. In earlier times, Maring produced salt for trade with neighboring groups, exchanging it for pigs, feathers, shells, and stone tools.

Maring culture is defined by a triad of pig husbandry, warfare, and ritual cycles. The best-known ritual, the kaiko, is a grand pig feast marking the conclusion of a long ceremonial period and traditionally preceding warfare. Men clear land, hunt, and build, while women garden, weed, harvest, and care for pigs. Gardening is typically done in male–female pairs (husband and wife, or brother and sister). Each clan cluster maintains a defined territory and cooperates in economic, ritual, and defensive activities. There are no chiefs or formal leaders; authority is based on consensus, persuasion, and demonstrated competence. Leadership is usually local and situational, extending no further than the subclan level. Social control depends largely on community pressure and adherence to taboos. While government courts exist, they are seldom used due to cost and cultural mismatch. Serious offenses such as wife stealing, sorcery, or pig killing traditionally demanded revenge.

Sumau

The Sumau, also known as the Garia, are named Mount Somau — their mythological place of origin — and inhabit the southern region of Madang Province. Their territory covers roughly 80–110 square kilometers (31 to 42 square miles) between the Madang coastal plain and the Ramu River Valley. The area consists of rugged low mountain ranges reaching 920 meters (3020 feet) at Mount Sumau, with dense rainforest interspersed by grassland patches. The dry season (February–October) is marked by intense social and ceremonial activity, while the wet season brings daily rains and time for craft production. [Source: Terence E. Hays, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Sumau population in the early 2020s was about 5,000 people. In of the mid-1970s, the Sumau numbered about 3,000 residents in their home region, with several hundred others working elsewhere in Papua New Guinea. The language is a Non-Austronesian language of the Peka family, closely related to Usino. Multilingualism is common, and most Sumau are fluent in Tok Pisin and many in English.

According to oral traditions, the Sumau originated to the west of their current homeland as the first humans, born from a sacred boulder and aided by a snake goddess. European contact began indirectly following Germany’s annexation of northeastern New Guinea in 1884. Explorers and recruiters were initially perceived as supernatural beings (magarai). Direct encounters increased during World War I, when young men were recruited for plantation labor. Lutheran missions were established in 1922, and by 1936 the Sumau had been incorporated under Australian administration with appointed headmen, courts, taxes, and enforced village settlement. Historically, warfare was rare and usually limited to feuds arising from sorcery accusations. Collective violence was replaced by football matches or ritualized compensation under colonial influence. During World War II, the Japanese occupied the Madang coast but had little contact with the Sumau; however, several cargo cults arose, blending traditional and Christian elements. Postwar years brought renewed mission activity, coffee cultivation, and the region’s political integration. The Sumau are now represented in the Usino Local Government Council, and both Lutheran and Seventh-Day Adventist churches are active.

The Sumau practice shifting cultivation on steep slopes, using fences to prevent erosion. Taro, yams, bananas, pitpit, and sugarcane are staple crops, supplemented by corn, coconuts, and introduced vegetables. Food shortages occur in the wet season, while the dry season yields abundance and supports feasts and pig exchanges. Hunting and fishing supplement the diet; domestic pigs are reserved for ceremonies and bride-price payments. Trade networks link the Sumau with both the Madang coast and the Ramu Valley. Pots are exchanged for shell valuables, tobacco, medicinal items, and weapons. Though trade stores now supply imported goods, traditional barter and partnerships remain active.

Sumau Religion and Culture

According to Joshua about 90 percent of the Sumau are Christians. Traditional Sumau religion viewed the universe as sustained by reciprocal relationships between humans and deities. Creator gods and goddesses were believed to have shaped the landscape, created humankind, and revealed secret spells for success in all endeavors. They lived corporeally in bush sanctuaries and could be invoked through ritual offerings. Spirits of the dead, as custodians of patrilineal estates, protected their descendants. Cargo cults of the 1940s adapted these beliefs, identifying God with traditional deities as the ultimate source of material wealth. Today most Sumau identify as Christian, but their religion remains a syncretic blend of Christian and ancestral beliefs.

Religious activity is largely individualistic. Each person seeks divine support through ritual offerings, while big-men coordinate collective ceremonies. The major ritual events are dry-season pig exchanges, which reinforce social networks and honor ancestral spirits. Male initiation ceremonies, held in three stages from puberty to marriage, teach ritual knowledge and strengthen solidarity among co-initiates.

The Sumau recognize three realms of the dead, all overseen by Obomwe, the snake goddess. Ghosts live in kin-based settlements mirroring the living world and may visit relatives in dreams. Violent deaths produce vengeful spirits. Traditionally, corpses were exposed on platforms and their bones preserved; since the 1920s, burial in cemeteries or near garden sites has become standard. After two or three generations, spirits are said to transform into flying foxes or bush pigeons.

Ceremonial occasions highlight Sumau artistry — floral and feather ornamentation, dance, and music using drums, bamboo stamping tubes, and flutes. Illness is attributed to sorcery, taboo violation, or ancestral displeasure, and is treated by ritual extraction, herbal remedies, and invocations to ancestral spirits.

Sumau Life, Family and Society

Traditionally, the Sumau lived in small, scattered hamlets of fewer than 50 people, consisting of separate men’s, women’s, and boys’ houses. During the colonial period (1920s–1950s), they were resettled into larger stilt-house villages of up to 300 people each. Since the 1950s, many have returned to smaller, shifting hamlets organized around local leaders or shared economic interests. Women and men share garden work but perform distinct roles. Women collect clay for pottery — the chief trade item — while men shape the pots. Other crafts include net bags, wooden bowls, bamboo flutes, and cassowary-bone daggers. Traditional stone tools have been replaced by steel implements.

Marriage is exogamous within the security circle and forbidden between close cognates to the second ascending generation. Preferred spouses come from neighboring groups. Bride-price payments, often extended over years, include pigs and goods. Polygyny is aspired to but rare due to its economic cost. A newlywed woman lives initially in her mother-in-law’s house before cohabiting with her husband.

Land rights pass through the male line but may also be acquired by purchase, especially by a sister’s son. Cognatic descent is recognized, but patriliny predominates. The Sumau employ an Iroquois kinship system that merges same-sex parental siblings and distinguishes cross-sex ones; parallel cousins are considered siblings, while cross cousins are preferred marriage partners.

The Sumau social structure revolves around security circles — Ego-centered networks of kin, affines, allies, and co-initiates obligated to mutual assistance. Close kin form the core; they cannot intermarry or act violently toward one another. Cooperation within these circles underpins economic and ritual life. Local leadership rests with “big-men,” influential figures who command respect through oratory, generosity, and ritual power. They organize ceremonies, resolve disputes, and mobilize labor but have no formal authority. Disputes over theft, adultery, or sorcery are typically settled in moots mediated by neutral kin, often ending in compensation or symbolic reconciliation. Social order depends on shame, gossip, and the withdrawal of cooperation rather than coercion.

Tambul

The Tambul people live at the foot of Mount Giluwe, the second-highest mountain in Papua New Guinea. The district is home to several distinctive tribes, with a combined population of just over 75,000 people. Located at the crossroads of the Western Highlands, Enga, and Southern Highlands Provinces, the Tambul region reflects a rich blend of cultural influences from all three areas—seen in its traditional dress, elaborate headdresses, striking face and body paint, and powerful dance performances that often resemble war cries. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Tambul’s traditional bilas (body ornamentation) features vibrant colors and impressive headdresses made from bird feathers. Men typically paint their faces with bold red and yellow stripes, creating a fierce, warlike appearance. Their songs and dances, performed during ceremonies and festivals, are characterized by rhythmic movements and chants that echo the energy of combat rituals.

Among the most prominent Tambul tribes are the Yano, Sipaka, and Kaniba. The Yano are especially noted for their courtship songs, which, like those of other Highland groups, often contain double meanings, one of which is usually sexual or flirtatious. The Kaniba are famous for their dramatic performance known as the “Box Contract,” a play that reenacts the story of Tambul’s first contact with Westerners.

Like their Melpa neighbors, the Tambul are renowned for their Moka exchange ceremonies—a traditional system of wealth transfer and social prestige. In a Moka, one man gives a gift, usually of pigs, to another, who is expected to reciprocate with a larger gift at a later time. Because few men can independently sponsor a Moka, they often borrow goods from their clan members, creating complex networks of mutual obligation. Status and respect within the community are tied to a man’s generosity and number of pigs owned. A “big-man”—a community leader or village chief—earns his reputation not through inheritance but by demonstrating wealth, influence, and the ability to give more than he receives.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025