Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

MADANG PROVINCE

Madang is a province on the northern coast of mainland Papua New Guinea. It has some flat areas but is also very mountains with some active volcanoes and many of the country's highest peaks. It is also ethnically with Papua New Guinea its biggest mix of languages. The capital is the town of Madang. [Source: Madang government]

Madang Province cover a land area of area of 28,886 square kilometers (11,153 square miles) and has a population, according to the 2011 census, of 493,906 people, with a population density of 17 people per square kilometers (44.3 people per square mile). Madang is the country’s fourth most populous province. Madang Province is an important agricultural region that produces a variety of crops, including coffee, cocoa, coconuts, and spices. The province also has natural resources, such as timber and minerals.

Madang Province has a diverse geography, including highlands, mountains, valleys, coastal areas, and islands. Each of these features presents unique challenges to development efforts in the region. The province also grapples with social issues, such as law and order problems, migration, internal displacement, and the high cost of delivering goods and services to remote areas.

Much of Madang Province is or was covered by steamy tropical rainforests with rich biotic diversity. There are two seasons: a wet season from December to May and a dry season from May to November. In some laowland areas, dense rainforest is crisscrossed by numerous streams and rivers used by local people for canoe travel and fishing. Because the yearly rainfall approximates 508 centimeters, these waterways flood and turn the rainforest into a swamp during the wet season. [Source: Leslie Conton,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The beautiful town of Mandang lies in middle part of the north coast and has with many parks. The chief attraction in the area is the gorgeous islands that lie offshore. Siar Island has good snorkeling and cheap bungalows. Kranket Island is larger and has several villages, a beautiful lagoon and equally good snorkeling and equally cheap bungalows. Both island are very close to Madang. It is also possible to walk to Mt. Wilhelm from Mandang.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Ethnic Groups in Madang Province

Madang Province is home to over 160 language-speaking groups, making it one of the most linguistically- and ethnically- diverse areas in the world. The Madang population can be grouped into four main communities: islanders, coastal people, Wagol River people, and highlanders. The Utu live about 30 kilometers northwest of Madang Town. They are almost all Christian, but like many other groups, they lack scripture in their language. Cocoa is a primary source of income for the area. The Domung live in the mountains of the Rai Coast and are swidden agriculturalists. They are mostly Christian, but some villages practice a cargo cult.

The Anjam live on the Rai Coast and take pride in their language, which is different from neighboring ones. They are subsistence farmers who also rely on fishing and have a syncretic blend of Christianity and traditional beliefs. The Medebur speak the Medebur language and are found near Bogia town near the North Coast Highway. They are mostly Christian, but their language lacks the New Testament. Their access to services can be disrupted by floods.

The Garingei and Garpunei, also known as the Malalamai people, they live on the east coast. They speak the Malalamai language and their ancestors are believed to have migrated from Southeast Asia. They are primarily Christians but still fear traditional magic.

Aiome inhabit the remote plains of the Ramu Valley. They maintain a strong cultural identity and are small in size.They have their own language and most identify as Christian. All the aforementioned groups have distinct languages and cultures.

The Imuri fire dancers of Upper Bundi, Madang Province wear headdresses made of Clay with a Burning flame on top of each head. They are found near the Snow Pass Resort of Mr Vincent P. Ambane Kumura, creator of the Snow Pass Culture Show. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

Kalam

The Kalam reside in the mountains in the Simbai region of Madang province and are known for their spectacular headdresses can reach a meter in height and are made from thousands of iridescent green beetle heads, bird of paradise feathers and furs. They are also known for their unique culture and strong connection to the forest.The Kalam have deep traditional knowledge, particularly concerning the diverse flora and fauna of their environment. [Source: Google AI; Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Due to their isolation, many Kalam people maintain a traditional lifestyle, living in huts built from local materials like pandanus leaves. The Kalam possess extensive and precise knowledge of the natural world, including a large vocabulary for local plants and birds, which they use for various purposes from medicine to hunting. The Kalam hold festivals, which are significant cultural events involving traditional dances and celebrations, and are sometimes open to adventurous visitors.

See Separate Article: FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM. ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

Waibuk

From SIL

The Waibuk are also known as the Haruai, Wovan, Taman and Wiyaw. Numbering around 4,000 according to Joshua Project, they speak a Harui language and live primarily in the Ararne River Valley in the Schrader Range of Madang Province. Their traditional religion focuses on the spirits of the deceased relatives, who are believed to inhabit stagnant water pools and large trees but venture into the village during the ceremonies surrounding initiation. Animal and forest spirits also affect the fortunes of humans, particularly in relation to hunting. About 10 to 50 percent of Waibuk are now Christian. [Source: James G. Flanagan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

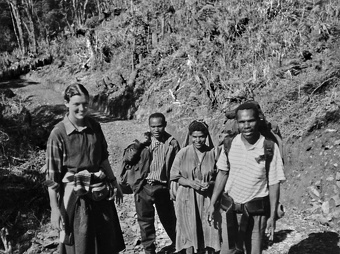

History: Cut off by a mountain spur running parallel to the Jimi River, the Waibuk remained undisturbed by European-Australian contact until 1962. That year, a patrol led by J.A. Johnston from Tabibuga in the Western Highlands Province entered Waibuk territory. While the Waibuk treated the outsiders with considerable suspicion and caution, no hostilities were reported. For many years, large segments of the population simply avoided the yearly government patrols when they passed through the territory. Only 161 people participated in the first census in 1968.

Village leaders, or luluai and tultul, were appointed by patrol officers to act as intermediaries between the people and the government. Government health and agricultural officers regularly visited Waibuk territory, encouraging changes in burial practices, improved hygiene, and the adoption of coffee as a cash crop. In the mid-1970s, a government-sponsored medical aid post staffed by a medical orderly was established at Fitako. In 1977, the Anglican Church established a mission station staffed by members of the Melanesian Brotherhood at Aradip. The Church of the Nazarene, a fundamentalist sect, established mission churches on the outskirts of Waibuk territory. Conflicting religious messages have caused considerable confusion among the Waibuk people, leading many of them to simply avoid the missionaries.

Waibuk Culture and Life

Despite government and mission pressure to settle in centralized hamlets, most Waibuk people continue to live in scattered ridge-top homesteads that follow their traditional pattern. These sites overlook valley gardens and usually house groups of related men, their wives, and children—ranging from small nuclear families to extended households of over thirty people. Houses are divided into male and female sections, with couples occupying opposite ends. [Source: James G. Flanagan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Artistic expression is seen in decorated arrows, drums, combs, and Jew’s harps, while festivals feature elaborate body decoration, singing, and drumming. Some men are known as gifted songwriters. All Waibuk males undergo an extended initiation sequence beginning in childhood and continuing into adulthood, culminating in elaborate adolescent rites marked by dancing and pork feasts. Most marriages result from elopement, often initiated by women. Brothers, rather than fathers, take leading roles in arranging marriages, though bride-prices are small and often unpaid. Residence after marriage is patrilocal.

Subsistence centers on taro and sweet potatoes, supplemented by bananas, sugarcane, maize, beans, greens, and tobacco. Wild foods such as betel nuts, pandanus, fungi, and marita fruit are gathered, and coffee has recently been introduced. Pigs, dogs, and fowl are kept; pigs are vital both for food and exchange, while dogs assist in hunting. Game includes cassowaries, wild pigs, birds, marsupials, and eels—the latter valued both ritually and nutritionally. Sago is obtained through trade from the Sepik region.

Although descent is ideally patrilineal, Waibuk social organization is fluid. Parallel-cousin marriage supports flexible land and resource sharing. Homesteads often form cooperative units for gardening, hunting, and exchange, linked through mutual gift-giving and partnership. Genealogical depth is shallow, and kinship ties emphasize reciprocity over lineage. Unlike the central highlands, Waibuk society lacks single, dominant “big men” leaders; all initiated men are regarded as numbe diib—“big men.”

Usino

The Usino people live primarily in and around Usino Patrol Post in the Ramu River Valley of Madang Province in an area of tropical rainforest between the Bismarck and Finisterre mountains. They have their own language (Sob or Sop) and unique traditional religion which has merged with Christianity, which has significantly influenced their culture. "Usino" — or Usino-Bundi — is also the name of the district where they live. Usino history is marked by early contact with German Lutheran missionaries, exposure to fighting during World War II, and the influence of cargo cults that flourished until the mid-1960s.

The name that the Usino generally call themselves is Tariba. The name "Usino" refers to the inhabitants of four lowland social and territorial units, or parishes, each of which corresponds to a dialect of the Usino language. While all speakers of the language are referred to as "Tariba" by the Usino people, they distinguish between mountain and lowland speakers. The section here focuses on the lowlanders, who call themselves "Usino Folovo" or "Usino Men," as "Usino" is the name of the central village in the lowland region. Prior to contact, these parishes rarely united as a single sociopolitical unit and had no collective name for themselves despite intensive social and linguistic alliances.[Source: Leslie Conton,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

As of the 1990s, the Usino lived in three major villages and seven hamlets in Madang Province in the Ramu River Valley near Usino Patrol Post, just east of the Ramu River. The Bismarck Mountains rise to the west and the Finisterre Mountains rise to about 1,200 meters (3,940 feet) to the east. The land is sparsely populated, with an average of 2.7 people per square kilometer. In 1974, 250 Usino people lived in three centralized villages. Since then, the population has grown to approximately 400 people, partly due to an increase in the birth rate and the return of migrant workers and their families. According to Joshua Project their population in the early 2020s was around 4,300

The term "Usino people" refers to the inhabitants of a geographic region rather than a language group. The Usino language, often referred to as Sop or Sob, encompasses groups in several mountain villages. It is closely related to Sumau (also known as Garia) in the Finisterre Mountains, as well as to Danaru and Urugina in the Upper Ramu Valley. These four languages comprise the Peka family of the Rai Coast stock of non-Austronesian languages. Most Usino people can understand at least one or two neighboring languages, and all except the oldest Usino women now speak Tok Pisin as well.

Usino History and Religion

Madang Province topographic map dreamstime

Little is known about the origins of the Usino people, though language evidence suggests links to the Madang coast to the east. Their first recorded contact with Europeans came in the late 1920s, when German Lutheran missionaries reached the Finisterre Mountains. For decades, only coastal Indigenous missionaries visited regularly. European patrols from Madang and Bundi came until the 1960s. Raiding characterized external conflict until the 1920s and 1930s when the Usino people voluntarily accepted pacification. Although relations with other groups are generally amicable, issues over exchange, land use, and sorcery occasionally require traditional dispute settlement methods, such as a moot or court, where the contending parties air their differences and seek consensus. [Source: Leslie Conton,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

During World War II, both German and local missionaries left, and the Usino fled to the bush during fighting between American and Japanese forces. When missionaries returned in the late 1940s and 1950s, they found that Christianity had been displaced by cargo cults, which thrived until the mid-1960s. An Indigenous Lutheran missionary resettled in 1980, but traditional beliefs remain strong.Before the Usino Patrol Post and airstrip opened in 1967, travel to Madang took four days. A road connection in 1974 linked the community to the coast and Highlands. However, when district headquarters moved to Walium in 1981, Usino lost its airstrip and health center, cutting off key cash income and deepening isolation.

Today, Christianity—mainly Protestantism—is the dominant faith. The Joshua Project reports that about 97 percent of Usino are Christian, with up to half being Evangelical, though traditional spirit beliefs continue. Secret ritual names of ancestral heroes and bush spirits remain central to Usino spirituality. These names, owned by patrilineages, give power to rituals for hunting, planting, warfare, healing, and feasting. Many sacred names were lost when missionaries destroyed them or when elders died without passing them on. Access to this spiritual power varies among men, who must give offerings and use ritual names to ensure success in daily life. Illnesses were once explained as manifestations of sorcery or soul loss and healers retrieved lost souls and performed cures. The last traditional healers died without passing on their knowledge in the 1980s, and people now rely on Garia healers and government health infrastructure.

Usino-Bundi women from the Post Courier

Rituals accompany nearly all activities—gardening, hunting, initiation, marriage, feasting, and death. Male initiation involves seclusion, trials, and dance, while female initiation, last held in 1975, was conducted by outsiders after local knowledge was lost. The spirits of the dead (gob) may cause illness if angered, and special hand-washing ceremonies cleanse mourners and lay these ghosts to rest. Those who die violently (kenaime) are considered especially dangerous and must be controlled through spells and secret names. Though the dead traditionally offered no aid to the living, during the cargo cult era people began to seek help from their ancestors in gaining material goods.

Usino Family, Marriage and Kinship

The basic domestic and economic unit among the Usino is the household, which may include a nuclear or extended family. Inheritance is patrilineal, based on descent through the male line, and becomes effective once bride-price and child-price are paid. Education is mostly informal, taught through observation and imitation. In the 1990s few children attended the distant primary school, and only a handful of men had completed high school. Parents discipline children through scolding or physical punishment to instill responsibility.[Source: Leslie Conton,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Polygyny is accepted but uncommon. It was practiced by about 18 percent of families in the 1990s and usually was initiated by co-wives. Preferred marriages occur within the same parish, often involving sister exchange, though partners may be chosen from other parishes when necessary. These ties link parishes through networks of kinship and trade. Divorce is common and carries little stigma. Because of limited wealth, bride-price payments are modest and often symbolic. While marriages are usually arranged by parents, young people increasingly choose their own partners, and women often select their second husbands. Postmarital residence is virilocal, and most people live their entire lives within Usino territory.

The largest social and territorial unit is the parish, composed of people linked to a named tract of land and forming a political group. Traditionally, there were four such parishes, now grouped into three villages. Each parish includes two carpels—exogamous patrilineages that form the core of Usino kinship. A man gains full rights to his wife’s and children’s lineage only after paying bride- and child-price; otherwise, children remain part of their mother’s patrilineage.

Usino kinship terminology differs from standard systems: paternal parallel cousins are classed as siblings, while cross-cousins are distinguished and socially significant. Age and generational order shape kin terms—parents’ younger siblings are equated with parents, while older ones are called “grandmother” or “grandfather.” Grandparents and grandchildren share reciprocal terms distinguished by gender, and great-grandparents and great-grandchildren even call each other “husband” or “wife.”

Land tenure follows hereditary rights within the parish, collectively owned by patrilineal kin. Land use is generally passed through men, but cognatic ties—through mothers or wives—often determine access. Those who move to another parish lose ownership of natal land but may retain hunting or fishing rights through kin ties. With little population pressure, borrowing land is easy, and long-term cultivation can lead to eventual ownership. Children inherit land from their father if bride- and child-price have been paid; otherwise, they remain members of their mother’s parish and inherit there.

Usino Life, Agriculture, Villages and Economic Activity

The Usino have traditionally practiced swidden agriculture, growing taro, bananas, sweet potatoes, yams, pumpkins, and tapioca in their gardens and coconuts, betel nut, papayas, and tobacco in village plots. Bush foods, fishing, and hunting — of pigs, cassowaries, marsupials, reptiles, birds, and insects — has supplemented theit diet. Pig raising is less important than in the Highlands. Many men once worked briefly on coastal plantations, but wage employment was rare as of the 1990s. Efforts to grow cash crops such as coffee, rice, and peanuts, or to raise cattle, have had little success. [Source: Leslie Conton,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Men have traditionally hunted, built houses and fences, carved canoes, organized exchange ceremonies, and performed ritual, magical, and oratorical tasks. Women have traditionally cared for children, cooked, collected firewood, wove net bags, and maintained gardens. Girls begin helping at age five, while boys enjoy more freedom until adolescence. Women help men thatch roofs, prepare gardens, gather small game, and assist with feasts. Both sexes fish, but use different methods, and women now often join men in cash-crop production.

Before mission contact in the 1930s, Usino families lived in scattered homesteads within parish lands. Later, under government pressure, they consolidated into a single large village, which later divided into two, the largest being Usino. Villages continually shift as families expand or relocate. Houses are rectangular, built from bush materials, and encircle a central clearing. Traditionally, men’s houses also served as cult houses, and menstrual seclusion was strictly observed — first in separate huts, later in partitioned house areas. Since the 1980s, seclusion remains customary but less formal.

Usino art is displayed in carved bowls, drums, spears, and dyed net bags, and though body decoration and dances. Long known as traders and artisans, the Usino exchanged carved bowls, canoes, drums, mats, bark cloth, baskets, and weapons across the Ramu Valley. Their forested lowlands provided rich trade goods — pigs, cassowaries, feathers, shells, and tropical crops like betel nuts and coconuts — highly valued by neighboring mountain groups. Positioned between the Bismarck and Finisterre ranges, Usino long served as a vital link between coastal and upland trade networks, maintaining strong exchange ties beyond their own communities.

Tangu

The Tangu (Tanggu) have traditionally lived on a series of steep, forested ridges in the Bogia Region of the Madang Province of Papua New Guinea approximately 24 kilometers inland from Bogia Bay. The term “Tangu” also refers to the Ataitan language spoken by both the Tangu "proper" and certain other related groups. The Tangu population was estimated at around 2,000 in 1951-1952 distributed throughout about thirty settlements of varying size. The population reached 3,000 in the 1990s. The Joshua Project estimates that their current population is around 8,200, of they say around 95 percent Christian.[Source: Richard Scaglion, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Although closely resembling their neighbors culturally, the Tangu regard themselves as a distinct community bound by kinship, trade, and exchange. Their most distinctive institution is br’ngun’guni, a form of public assembly where grievances are debated and resolved. German officials first contacted the Tangu shortly before World War I, but Australian administration and a Society of the Divine Word mission in the 1920s had greater influence. In the mid-20th century, Tangu communities were drawn into millenarian cargo cults led by the prophets Mambu (1930s–40s) and Yali (1950s).

Tangu culture is noted for its “Watur” (Yam) tradition, which includes the building of mammoth yam towers, and traditional crafts and accessories such banana fiber underskirts, pandanus-fiber overskirts, bark-cloth breechclouts, woven-cane ornaments and waistbands, and string bags. Slit gongs and hand drums are still made, but without the carving, incising, pigmentation, and decoration that they formerly had. ~

In the 1990s the Tangu population was roughly grouped into four named neighborhoods. Each neighborhood contained one or more large settlements of twenty or more houses, as well as several smaller settlements, some of which comprise only a few homesteads. These settlements were strung out along a series of steep, interconnected ridges. Garden sites were scattered throughout the surrounding countryside. The Tangu people at that time usually had temporary bush settlements associated with hunting and gardening areas far from the main village, and they may have lived in them for several weeks at a time.

Religion: The Tangu spiritual world includes divine beings (puoker), water spirits (pap’ta), and ghosts of the dead, who eventually become ancestral spirits. These beings can affect human life but are unpredictable. Feasts and dances mark social events, and formerly, rituals accompanied circumcision.Death is treated pragmatically, with burial occurring within hours. Valuables were once interred with the body, and mourning occurs privately through drumming on slit gongs. Each person possesses a gnek—a soul or mind—that becomes a ghost and later an ancestral spirit. Sorcery (sanguma) was once integral to Tangu belief but became contentious as practitioners demanded high fees, prompting local movements to suppress it.

Tangu Life, Family and Marriage

Tangu women have traditionally cooked, weeded, looked after young children, and have done certain craftswork, such as making string bags. Men have traditionally hunted, built houses and shelters, and did other craftswork, such as wood carving. Garden work is carried on by both sexes, although the sexes once again perform slightly different tasks, with men doing most of the heavy felling, clearing, and digging and women doing most of the daily carrying, weeding, and cleaning. [Source: Richard Scaglion, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Because of the clear sexual division of labor, few Tangu remain unmarried. Marriage establishes cooperative exchange ties between the husband’s and wife’s families. Ideally, unions are arranged between the children of friends or between certain cross cousins (children of a brother and sister). Betrothal may last several years, during which the groom’s family presents pigs, dog-tooth chaplets, and other valuables to the bride’s kin. The engaged couple initially observe avoidance but later exchange labor between households. At the wedding, the wife’s brothers host the husband’s family, canceling betrothal debts and initiating lifelong exchange relationships between the two families. Either spouse may end the marriage, though close interfamily ties make divorce rare. Secondary marriages—often with a sister of the first wife or a divorced woman—are informal and sealed by small payments.

Young children remain with their mothers and maternal aunts, learning domestic and horticultural skills. Girls follow a steady path to womanhood, mastering cooking, weaving, and caregiving. Boys, around age six, move under paternal and maternal-uncle guidance, learning gardening, hunting, and ritual arts. Formerly, adolescence involved seclusion, circumcision, and initiation in a men’s clubhouse, now largely abandoned. A “sweetheart” (gangaringniengi) relationship with a cross cousin provides sexual education through courtship and affection. "Sweethearts" dance, sit together, flirt, and fondle and stroke one another, engaging in love play. Breast and penis stimulation are common, but sexual intercourse is formally prohibited.

Tangu Society, Agriculture and Economic Activity

The Tangu have no chiefs; instead, clusters of households are guided by wunika ruma—energetic and respected big-men who lead by example through productivity and eloquence rather than formal authority. Traditionally, communities consisted of two exogamous intermarrying groups, or gagawa outside their own group. Households formed long-term exchange partnerships with those of the opposite group, relationships that continue today and link families across communities through marriage and friendship. Tangu society thus functions through a web of reciprocal obligations rather than centralized control. [Source: Richard Scaglion, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Tangu are primarily swidden horticulturalists cultivating yams, taro, and bananas as staples, supplemented by sago, breadfruit, sugarcane, coconuts, and greens. Recently introduced crops include maize, tapioca, and sweet potatoes. Pigs and chickens are kept domestically, and hunting and foraging provide additional protein from pigs, cassowaries, marsupials, and birds. Fishing is done with spears, hand nets, or plant poisons. Subsistence is supplemented by occasional wage labor.

Tangu produce many utilitarian goods — banana-fiber and pandanus skirts, woven bands, string bags, and fishing nets. Slit gongs, hand drums, and Jew’s harps are made for music and communication. Their only commercial crafts are coil-made clay pots and string bags, traded both within Tangu and with neighboring peoples. Two neighborhoods specialize in pot-making, and two in string bag and sago production. Traditional exchanges include pots, sago, dogs, tobacco, and betel nuts, now joined by trade-store goods from mission posts, which circulate widely through local barter networks.

Aiome

The Aiome are a small people — also known as the Gainj, Aiome Pygmies, Gants and Ganz — that traditionally lived in the Takwi Valley of the Western Schrader Range in Madang Province on the northernmost fringe of the central highlands. The valley covers approximately 55 square kilometers (21.2 square miles) and receives almost 500 centimeters (200 inches) of rain annually, In the 2020s, the Aiome were reported living on the remote plains of the Ramu Valley, one of the remotest parts of Madang Province, in villages about 200 kilometers west of the provincial capital, Madang in the Middle Ramu District and the Simbai Local Level Government area. [Source: Patricia L. Johnson and James W. Wood, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~; Joshua Project]

According to Joshua Project there about 1,900 Aiome, up from 1,500 in the 1990s, when they lived in approximately twenty widely dispersed local groups, which varied in size from about 30 to 200 individuals. A continuous process of fission and fusion traditionally maintained the total number of groups at a fairly constant level. In the 1990s, population size was kept low by low fertility and density-dependent mortality. Life expectancy at birth was 29 years for females and 32.4 years for males; the infant mortality rate was about 165 per 1,000 live births, with a slightly higher rate for females than for males. ~

History: The first known contact by the Aiome with whites was with the Australian colonial government in 1953. The Aiome remained largely unaffected until the establishment of the Simbai Patrol Post 30 kilometers to the west in 1959. The area was declared pacified in 1963, after which male labor recruitment for coastal plantations began and continues today. The Anglican Church established a mission in 1969 and a school in 1974; both are now administered by the provincial government. A significant event in Aiome history was the introduction of coffee as a cash crop in 1973. This led to the development of a road and an airstrip in the area in the 1980s. The new routes out of the valley, along with pacification, have led to more extensive relations with neighboring groups and the migration of some Aiome into lowland areas near Aiome."

Language: The Aiome (Gainj) language is classified with Kalam and Kobon in the Kalam Family of the East New Guinea Highlands Stock of Papuan languages. Many Aiome still speak the Aiome language as their primary language. Many Aiome are multi-lingual, most commonly in Kalam. Many can use Tok Pisin or English when at the market or if they see people from outside of their area.

Religion: According to the Christian-group Joshua Project about 90 percent of Aiome are Christian, mostly Anglicans. Traditionally, the Aiome believed in malevolent spirits, associated with mythical cannibals and sorcerers, inhabited the permanently cloud-covered primary forest of higher altitudes. Each kunyung (territory) is said to have such a place associated with it that is safe for members but dangerous for nonmembers. Ancestral ghosts are believed to be at best neutral; at worst they are malevolent and cause illness and death among the living. There is a pervasive fear of human sorcerers. All deaths are believed to be caused by sorcery or by malevolent spirits. Ancestral ghosts are thought to inhabit the areas in which they died and may visit evil upon the living. They can be ritually appeased; sorcerers cannot.

Aiome Family, Marriage and Society

An Aiome household — ideally a nuclear family, although many households do include nonnuclear members — primary unit of consumption and production. Aiome society was organized around kunyung (nonoverlapping, named territories which have operated as ritual and political entities. Kinship is bilateral, with no descent groups; key affiliations are the family, kindred, and kunyung. [Source: Patricia L. Johnson and James W. Wood, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Marriage is nearly universal. The exogamous unit (existing outside a group) is the bilateral kindred ( a person's network of relatives through both their mother's and father's sides of the family, where kinship is traced equally through both lineages). Kunyung exogamy is preferred rather than enforced. Sister exchange is allowed but uncommon, and other marriages require modest bride-wealth. Once children are born, divorce is rare. Residence is generally patrivirilocal (living in the husband’s family home or community). While polygyny is valued, most unions are monogamous. Men usually remarry, and widows’ remarriage depends on the number of their children.

Children are mainly raised by mothers and maternal kin. Boys, initiated between ages 10 and 15, move to bachelors’ houses, while girls remain within the household learning domestic work. Discipline is mild, and children learn through experience. Inheritance consists only of personal property, passed mainly along same-sex lines.

Two Aiome men, standing next to Lord Moyne, holding spears and bow and arrows, with battle axes, tapa head coverings, nose ornaments and loin coverings; a thatched building and trees and other vegetation visible behind them; Atemble, Papua New Guinea; from the British Museum

Land use follows the principle Yandena ofu (“I make gardens”) — rights derive from cultivation rather than ownership. Individuals garden in territories linked to kin or marriage and may use land in multiple kunyung. Both sexes enjoy broad access. Land reverts to the communal pool once abandoned, though trees can be individually owned and inherited.

Traditionally, kunyung acted collectively in ritual and warfare. Membership is fluid and based on shared nourishment from local gardens rather than descent. Local big-men gained temporary influence through fighting skill, but there were no hereditary positions or competitive exchange systems like those of the central highlands. Today, political unity finds expression in ritual dancing and business cooperatives led by “big-men” of commerce.

Social control relies less on formal law than on gossip, public opinion, and fear of sorcery. Historically, warfare occurred between kunyung or against neighboring Kalam, usually in small-scale raids rooted in personal disputes or revenge. Since pacification, open conflict has declined, but sorcery accusations had grown as of the 1990s — turning warfare, as locals say, into “secret fighting.”

Aiome Life, Settlements and Economic Activity

Traditionally, Aiome settlements were widely dispersed, with no true villages or nucleated hamlets. Houses were scattered within bounded, named territories (kunyung), which functioned as both territorial and social units. Sites were chosen for level ground, water, and proximity to gardens. Each ovoid house, built with wooden frames and bark walls under sago-thatch roofs, was typically occupied by a nuclear family and served mainly for sleeping and storage. Centralized village patterns have developed only in recent decades.

Women perform most daily labor — cultivating gardens, collecting wood and water, caring for children and pigs, preparing food, weaving string bags and skirts, and maintaining coffee plots. Men’s work is more intermittent and ceremonial: they clear gardens, build houses, hunt, plant and market coffee, and direct ritual and political affairs.

The nyink dance remains the major ceremony, once associated with male initiation but now used to mark public events such as the opening of trade stores or business cooperatives. Men adorned with elaborate headdresses perform songs and dances through the night, while debts are settled and marriage payments initiated.

The Aiome are classic slash-and-burn horticulturalists, cultivating sweet potatoes as their staple, with taro, yams, bananas, sugarcane, pandanus, pitpit, and greens as supplements. Introduced crops—corn, pumpkins, cassava, papayas, and pineapples—are grown in small quantities. Pigs and chickens are kept for exchange rather than food, while hunting provides little dietary contribution. Since the late 1970s, Aiome have become major coffee producers for Madang Province, and local cooperatives now use profits to operate trade stores and purchase imported goods.

Traditional crafts include string bags, skirts, mats, and weapons. Formerly, Aiome traded bird-of-paradise plumes and marine shells between coastal and highland groups. Today, they continue regional trade, notably selling lowland cassowaries to the central highlands for use in bride-wealth payments.

Healing was once the domain of traditional specialists who used herbal medicines, including ginger and nettles, but these practices have declined under missionary and government discouragement. Western medicine is now favored, though fear of sorcery and ancestral displeasure continues to shape local understandings of illness and misfortune.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025