Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

MELPA

Melpa dressed in ceremonial clothing for a wedding; From Miller’s Time

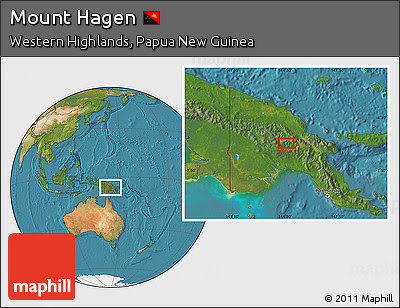

The Melpa are a relatively large ethnic group centered around the town of Mount Hagen in the Western Highlands Province. They are well-known for their ceremonial exchange system, the moka, where individuals gain prestige by gifting pigs, shells, and money to others. Body decoration is a major art form, with participants in festivals painting themselves and wearing elaborate headdresses made with feathers and other materials. Yodeling is used for long-distance communication in rural areas.

Melpa are also known as Hageners, Mbowamb and Medlpa and their territory is bounded on the west by the Enga and on the east by the Wahgi peoples. The Melpa are some of the first Papuans that tourists and visitors to Papua New Guinea see when they step off the plane at Mount Hagen airport, where they sell modern "stone axes," colorful string bags, and other artifacts. Some also provide taxi and bus service to the local hotels and guesthouses.

Many Melpa are over six feet tall. According to the Christian organization Joshua Project, the Melpa population in the 2020s was about 144,000. In the 2000s it was estimated at 130,000. In the 1990s more than 60,000 Melpa speakers lived in areas north and south of Mount Hagen. Population density varied with ecology—rising above 134 people per square kilometer in parts of the Wahgi Valley and Ogelbeng Plain near Mount Hagen, and dropping below 19 persons per square kilometer in the northern region known locally as “Kopon” (Dei Council area). Since the colonial period, population growth has averaged just over 2 percent annually.

The Melpa live in the Western Highlands Province. The area they live in consists of montane valleys and mountain slopes, varying between 400 and 2,100 meters (1,312 to 6,890 feet) above sea level. The bulk of the population lives at altitudes between 1,500 and 1,800 meters (4,921 to 5,905) above sea level. The Melpa occupy the areas north and south of the important town of Mount Hagen. The greatest area of population density just outside Mount Hagen in the Wahgi Valley and nearby Ogelbeng Plain. The climate in the area is relatively mild, especially by tropical standards. The temperature rarely exceeds 30°C (86°F) in the summer months and rarely falls below freezing in winter. The climate is marked by a relatively wet period from October to March and dry from April to September. Annual rainfall is in excess of 250 centimeters (100 inches). In the dry season there may be periods of drought and nocturnal frost. Otherwise, the climate is benign enough so crops can be planted throughout the year. Mosquitoes are nonexistent here and malaria is, therefore, not a problem. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Melpa History

From Miller’s Time

The Melpa were the first highlands people of New Guinea to be encountered by Europeans, in 1933. Until that time, the New Guinea highlands had been completely unknown to the outside world, and the highlanders themselves had never seen anyone from beyond their valleys and mountain plains. The first meeting between these groups was captured on film, providing a remarkable and invaluable record of this historic moment of discovery for both sides. [Source: J. Williams, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life, Cengage Learning, 2009]

Intensive horticulture has been practiced in the Melpa region for about 9,000 years. Early cultivation took place in fertile, drained swamps and later expanded to the surrounding hillsides when sweet potatoes—introduced only a few hundred years ago—replaced taro as the staple crop. Long-distance trade networks brought in shell valuables, decorative bird plumes, salt, and stone axe blades from distant regions. [Source: Andrew Strathern, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Before “pacification,” revenge served as the primary motive behind many acts of violence among the Melpa. “Pacification” refers to the period when European missionaries sought to persuade the tribes to adopt more peaceful behavior. Revenge killings often set the men of one clan against another, resulting in prolonged skirmishes that could last months or even years. Although this mindset has not been entirely eliminated, the most significant transformation in Melpa society has been the decline of inter-group warfare. Younger generations are increasingly adopting modern values, while traditional ideals that once emphasized warfare, sorcery, and ritual knowledge are gradually being replaced by the pursuit of material prestige. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Conflict has long been a part of Melpa social life, balanced by strong traditions of friendship and reciprocal exchange among kin and trading partners. In the past, force often played a central role in intergroup relations, though disputes were tempered by the diplomacy of influential big-men. Today, political violence between groups remains a serious issue, driven both by ongoing economic changes and enduring traditions of revenge. Within communities, conflicts were traditionally resolved through open discussion forums, or moots—now largely replaced by official Village Courts and other formal legal institutions.

Europeans first entered the Melpa region in 1933 during a gold prospecting expedition. The Leahy brothers—Michael, James, and Danny—along with Australian Patrol Officer James L. Taylor, led the exploration and early efforts at pacification. Mount Hagen soon developed as the regional center for administration, trade, and mission work. Until the 1950s, contact with the outside world was mainly by air, but today the Highlands Highway connects the area to the coastal port of Lae, serving as its primary route for goods and transport. Under Australian colonial rule until 1975, the Western Highlands was a district; after Papua New Guinea’s independence, it became a province with its own assembly and government, alongside representation in the National Parliament. Tribal warfare resurged during the 1970s and 1980s with the partial decline of government authority.

Melpa Language

The Melpa language belongs to the East New Guinea Highlands stock of non-Austronesian languages, within the Central Family of that group. Closely related languages are spoken in the Nebilyer Valley, Tambul, and Ialibu to the south, while Wahgi and Chimbu languages lie to the east, and Maring, Narak, and Kandawo languages to the north. [Source: Andrew Strathern, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Melpa is linguistically related to Chimbu, spoken by the neighboring Chimbu people to the east. It has over 130,000 speakers, primarily in Mount Hagen and the surrounding areas of Western Highlands Province, and is spoken by the Kawelka and other related tribes. Many Melpa also speak Tok Pisin, one of Papua New Guinea’s official languages, as a second language. However, Melpa remains robust, with most children still learning it as their first language. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

A distinctive feature of Melpa is its use as a pandanus language during karuka (pandanus nut) harvests. It includes a rare velar lateral sound, represented by a double-barred “l,” and employs a binary counting system. A comprehensive dictionary of Melpa was compiled by Stewart, Strathern, and Trantow in 2011. The Temboka dialect is spoken by the Ganiga tribe, who featured prominently in Robin Anderson and Bob Connolly’s acclaimed Highlands Trilogy documentaries (First Contact, Joe Leahy’s Neighbours, and Black Harvest). The film Ongka’s Big Moka also features dialogue in Melpa. [Source: Wikipedia]

Melpa Religion

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 99 percent of Melpa are Christians and 10 to 50 percent are Evangelical Christians. Christianity has existed in the Melpa region since the founding of Mount Hagen as an administrative, trade, and missionary center after the first Leahy expedition in 1933. Many Melpas attend the local churches on a regular basis although many traditional supernatural beliefs still exist.

The majority of their non-Christian religious practices center around the ghosts of dead family and clan members to whom pork sacrifices were made in cases of sickness and at times of Political danger (such as prior to warfare). In addition, circulating cults moved through the area, exported from group to group. [Source: Andrew Strathern, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

From Miller’s Time

Death among the Melpa is observed with extensive mourning rituals followed by a funeral feast, during which gifts are given with special attention to the deceased’s maternal relatives. In the past, bodies were exposed and later disarticulated so the bones could be used in family shrines, but today burials have replaced these practices. Traditionally, the dead were believed to journey along waterways to a place in the northern Jimi Valley known as Mötamb Lip Pana. Spirits of the departed are thought to return in dreams and to continue influencing the living, either helpfully or harmfully. In earlier times, small skull houses were built for offerings and personal sacrifices. While baptism and Christian burial are now common, belief in ancestral spirits remains strong and continues to shape Melpa interpretations of misfortune and the blending of indigenous and Christian traditions.

The Melpa have religious experts (mön wö) who are responsible for curing the sick and act as intermediaries between the human world and the spirit world. They were significant in both local and circulating cults. They were both curers and intercessors between people and spirits. Some learned from their fathers, others by apprenticeship to existing experts. Women are not allowed to be curers but could become mediums possessed by spirits allowing them to foretell the future and reveal secrets.

Melpa Customs: Moka and Redistribution

The most important ceremonial event in traditional Melpa society was an exchange ritual known as the moka (or tee) ceremony. In this ceremony, one man presented a gift to another, who later repaid it with a larger gift, thus giving “something more.” These reciprocal partnerships continued throughout a man’s adult life. To sponsor a major moka, men would solicit contributions from their clansmen, gathering as much wealth as possible. Before European contact, the most valued exchange items were pigs—both live and cooked—and kina or pearl shell ornaments. In modern times, money, machetes, and even vehicles have joined the list of prized gifts.

The goal of the moka was not personal enrichment but prestige: men sought to gain status by out-giving others. Those who excelled at this became known as “bigmen,” respected leaders in the community. Unlike Western ideals of accumulating assets, the Melpa viewed wealth as something to give away. Anthropologists describe this system as redistribution, in which the purpose of accumulating goods is to circulate them, not to keep them. Each moka created an obligation to return an equal amount plus more, forming an ongoing cycle of generosity and debt.

Although large-scale moka ceremonies have largely disappeared today, the principle of “big-manship” remains a key marker of leadership and prestige in Melpa society.

Melpa Initiations and Festivals

The climactic ceremonies of the circulating cults were grand public events in which male participants emerged from the cult enclosure to dance and distribute pork to hundreds of guests. The Hagen and Goroka Festivals, along with the traditional Tee (or moka) ceremonies, were all designed to encourage reconciliation among rival clans and reduce intergroup hostility. The aim of these exchanges was to gain prestige within the community by giving more than one received. Status and reputation were built through generosity, as each man sought to establish numerous exchange partnerships.

The Mount Hagen Show remains one of the most important cultural celebrations for the Melpa. Held every two years, it attracts groups from across the Highlands who gather to perform traditional songs, dances, and music while wearing elaborate ceremonial attire. Dancers, often in grass skirts, form chorus lines and move rhythmically to the beat of drums, symbolizing unity and strength among warriors. Body decoration reaches its peak during this event, with participants adorned in feathers, shells, and face paints of vivid red, black, and white. Red pigment, often worn by women, represents fertility and friendship toward the opposite sex. For the wives of deceased chiefs, traditional attire once included large gourds that covered most of the chest.

Beyond their economic and social importance, moka gatherings also serve as major regional festivals, drawing large crowds and showcasing the vibrancy of Highland culture. Today, while urban Melpa in Mount Hagen observe national holidays such as Independence Day, many rural Melpa do not, as such occasions have little impact on their daily lives.

In the past, the Melpa practiced elaborate male initiation rituals, but these have largely disappeared through contact with the outside world. As part of their traditional rites of passage, boys left their mothers’ houses around the age of eight to reside with the men. Unlike many other Highland groups, the Melpa did not socially mark a girl’s first menstruation with ceremony or seclusion. [Source: "Vanishing Tribes" by Alain Cheneviére, Doubleday & Co, Garden City, New York, 1987]

Melpa Family and Marriage

Melpa society is patrilineal (based on descent through the male line) and clans are created from individuals who share a male ancestor.Melpa society is patrilineal, with descent traced through the male line. Clans consist of individuals who share a common male ancestor, and marriage within one’s own clan is strictly forbidden. Spouses must come from outside the clan. After marriage, a couple resides in the groom’s father’s village until a separate residence can be built for the bride near the men’s house. A newly married couple may either construct a new women’s house for the bride or occupy space in an existing one. Over time, they establish their own household close to the husband’s settlement. Divorce does occur and can be costly. It is marked by the return of part of the bride-wealth, particularly if the woman is considered at fault or has borne no children for her husband’s clan. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *\; Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels; [Source: Andrew Strathern, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Marriage is established through an exchange of bride-wealth payments, which are substantial and require the cooperation of the extended kin group. Traditionally these payments consisted of pigs and shell valuables; today, cash is also common. The majority of the payment is made by the groom’s family and kin to the bride’s family as compensation for the loss of their daughter. The bride’s family, in turn, presents return gifts—most notably breeding pigs over which the bride retains considerable control. Residence is normatively patrivirilocal, with the wife joining her husband’s family or community.

The bride price generally reflects the perceived value of the woman. A young woman known for her skills—such as cooking or sewing—commands a higher price. This practice contrasts with the concept of a dowry, which is a payment made to the groom or used by the bride to establish her household. Traditionally the bride price included pigs and shells, though cash payments have become increasingly common. The bride’s family often provides the new couple with a number of breeding pigs. Negotiation of the bride price is a crucial part of the marriage process, and failure to reach agreement can result in the cancellation of the match.

Childrearing is generally gentle, and children are treated with tolerance. After childbirth, a postpartum taboo is observed for two to three years, during which children are breastfed. There are no formal initiation ceremonies for either sex, but boys move to the men’s house before puberty. Puberty for boys is marked by the wearing of a wig made from human hair. Traditionally, both boys and girls learn through observation—the “look and learn” method—but today most children attend at least primary school.

Inheritance focues mainly on land. Property is distributed according to the needs of children at marriage. Because the Melpa are a male-dominated, patrilineal society, most land passes to sons, although married daughters may retain cultivation rights at their natal homes. Fathers often grant land to their sons upon marriage, while daughters, though ineligible to inherit land outright, may receive gardening rights to specific plots.

Melpa Men and Women

Traditionally, men and women maintained separate residences. With the arrival of missionaries, the practice of family households—where the husband, wife, and children slept together—was encouraged. More modern-minded Melpa have since adopted this arrangement, while more traditional members continue to uphold the older custom of separate living quarters. Traditionally, women and their unmarried daughters live in rectangular women’s houses, which also contain stalls for pigs to prevent them from wandering off or being stolen. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Women control the production in Melpa society, including the cultivation of gardens and the all-important pig husbandry that is the center of the Melpa exchange universe. Men must rely on their wives as producers and as such, women wield considerable political power in Melpa society. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

Melpa Men create garden areas, fence them, and plant cash crops. They clear the land and plant banana trees and sugarcane and coffee which bear fruit above ground. Women cultivate taro and yams — Melpa staples — which are grown underground. They also plant greens and harvest gardens and keep them free of weeds, and they are also largely responsible for feeding the pig herds that are essential to the prestige economy. The fences men build serve to keep out the pigs that graze and root in the area.

Like many groups in Papua New Guinea, the Melpa emphasize sexual separation and opposition. Gender differences are often accentuated to the point of ambivalence, mistrust, and even fear. There were strong beliefs about the need to separate men and women to prevent male “pollution” through contact with menstrual blood. Despite this, Melpa girls enjoy considerable autonomy in choosing their spouses. Although families may prefer certain alliances, they generally recognize that forcing a daughter into marriage only brings unhappiness for all involved.

Melpa Society and Kinship

Descent among the Melpa is primarily patrilineal (traced through the male line), though significant importance is also placed on matrilateral (mother’s side) ties and family alliances. These relationships are often reinforced through exchanges and, in cases of internal conflict or potential economic advantage, by temporary residence shifts to the maternal group. Exogamous clans (those that marry outside their group) are organized into tribes, which are further divided into subclans and smaller units that cooperate in exchange activities. Clans are mainly connected through marriage and the exchange networks that result from it. Within a tribe, clans were traditionally expected to support one another during serious warfare, though internal conflicts between clans were not uncommon. Land is typically inherited by sons from their fathers as they mature and marry. Daughters may receive land for their own use even after marriage, but because marriages are generally virilocal (with the wife residing in the husband’s community), women usually tend gardens on their husbands’ clan lands. [Source: Andrew Strathern, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Melpa kinship terminology follows the Iroquois system, which uses bifurcate-merging distinctions for relatives. In this system, a father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are referred to by the same terms as “Father” and “Mother,” respectively. Conversely, a father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers are identified by separate non-parental terms, equivalent to “Aunt” and “Uncle.” The children of a father’s brothers or a mother’s sisters (parallel cousins) are referred to by the same terms used for siblings, while the children of a father’s sisters or a mother’s brothers (cross cousins) are distinguished by different terms, corresponding to “cousin” in English. Most kin terms are self-reciprocal in address, though not in reference. [Source: Wikipedia]

A man with numerous exchange partners and the ability to distribute considerable wealth is known as a “big-man” (wö nuim), who does not inherit a formal title but attains prominence within the moka exchange system through his generosity and the support of his kin. Big-men often incur substantial debts, yet their influence allows them to take multiple wives, arbitrate clan disputes, and have land cultivated by others. In precolonial times, big-men maintained monopolies over shell wealth, which diminished after Europeans introduced large quantities of shells. Bamboo necklaces symbolized wealth, each representing the gifting of at least eight kina. Big-men were selected by a council of elders and bore responsibility for organizing and financing moka exchanges. They were also expected to be skilled orators and negotiators. Today, the traditional big-man system coexists with modern political institutions, including elected councillors, provincial representatives, and members of the National Parliament, who serve four- or five-year terms.

Before pacification — the period when European missionaries sought to impose peace — revenge was a major motive behind Melpa violence. Retaliatory killings frequently set one clan’s men against another, sometimes escalating into extended conflicts. Although less common today, the impulse for revenge has not vanished. Even in modern times, hundreds of men dressed in full war attire have been seen rushing along the Highlands Highway to confront neighboring villages in retribution for past wrongs. Such incidents often alarm tourists and prompt government warnings against travel in the area. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures, The Gale Group, Inc., 1999]

In the 1990s, mortality rates among the Melpa were high. Infant mortality was 57 deaths per 1,000 live births, child mortality at 15 per 1,000, and maternal mortality at 80 per 1,000. The leading causes of death at that time included pneumonia, malaria, and typhoid. Based on the 2000 national census, life expectancy was 53 years for women and 54 years for men.

Traditionally, Melpa education emphasized the socialization of youth into capable and responsible community members. Today, public and parochial schooling complement these traditional methods. In the Highlands, Western-style education has been integrated with indigenous knowledge, producing individuals who navigate both traditional and modern worlds simultaneously.

Melpa Life

From Miller’s Time

Like other Highland societies, the Melpa traditionally relied on sweet potatoes, taro, and pork as staple foods. Pigs, highly valued as both a measure of wealth and an essential trade item, are nevertheless eaten on important occasions. While sweet potatoes remain a key dietary staple, Western-style foods—such as tinned fish and instant noodles—have become increasingly common due to their easy availability in trade stores and the central marketplace of Mount Hagen.

Gender roles among the Melpa remain traditionally defined. Men are responsible for building houses and fences, clearing and planting gardens, and defending the village. Women care for children, manage household duties, tend pigs, and plant, weed, and harvest crops. In modern times, many Melpa have taken up employment in Mount Hagen, working as taxi drivers, airport porters, or shop assistants.

In more remote areas, villages are often separated by deep valleys and rugged mountains. Unlike most of the world, which remains closely connected through modern communication technologies, much of the Highlands lacks electricity and cellular service, making long-distance communication extremely difficult. The Melpa have developed an ingenious solution: yodeling. Greetings, directions, commands, and even disputes are often communicated through melodic yodels that echo across ravines and ridges—exchanged entirely without visual contact between the parties. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Traditionally, big-men were versed in a range of spells and rituals used to cure sickness. Most adults were familiar with a few herbal remedies, though illness was often attributed to moral or spiritual causes. Misconduct within a group was believed to provoke retribution from ancestral ghosts or from the group’s mi—a sacred being or object linked to clan origins. To appease these forces, indigenous sacrifices were performed. Today, most Melpa seek healing through Christian prayer—in Catholic, Lutheran, Pentecostal, or Seventh-Day Adventist churches—and through modern medical care at hospitals and aid posts. However, some traditional healers, or big men, continue to practice their craft.

In some parts of the Highlands, hamlets are separated by deep valleys and steep mountain ridges. This is especially true in the more remote Melpa regions, where settlements can be widely spaced apart. In these isolated areas, communication is often carried out over long distances through yodeling. Men exchange greetings, requests, directions, commands, and even challenges by yodeling across ravines or ridges—often while remaining completely out of visual contact with one another.

Melpa Villages and Houses

Traditionally, Melpa houses were constructed on mountain tops, chosen for their strategic advantage in times of warfare. Rather than being clustered into compact villages, dwellings were often scattered throughout the rainforest, with each homestead standing independently. A typical settlement contained at least one men’s house and one women’s house, with extended family homesteads located near their gardens within clan territory. Members of a clan generally lived in close proximity, their homes and gardens connected by a network of footpaths. [Source: Andrew Strathern, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

Men’s houses were typically round with conical roofs, serving as communal dwellings for men and boys from about eight or nine years old. Women’s houses, by contrast, were long and rectangular, often incorporating enclosed stalls for pigs to prevent them from straying or being stolen at night. In some settlements, particularly those associated with a big-man (a political leader), a ceremonial ground was also present for rituals and community gatherings.

Traditional Melpa houses were built using wooden posts, bark, woven cane, and thatching grass. With the arrival of missionaries, “line villages” were introduced—rows of family homes designed so that husbands, wives, and children could sleep under the same roof. While some Melpa communities adopted this new residential pattern, others chose to maintain traditional housing arrangements.

Today, roads and footpaths connect many hamlets, linking them to each other and to the Highlands Highway, which runs through the central mountain range and provides access to larger towns such as Mount Hagen.

Melpa Culture

Myths and oral traditions play a vital role in Melpa society. Stories recounting the origins of clans continue to be told, often linked to sacred objects or living beings known as mi, which are believed to embody the clan’s ancestral spirit. Long orations and epic narratives are performed to celebrate the heroic deeds of clan ancestors. Prominent in Melpa mythology are tales of the “Female Spirit,” called Amb Kor in the Melpa language, whose stories are widespread and deeply woven into their oral literature. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *\; Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Vocal music holds special importance in Melpa culture. As in many other Highland societies, courtship songs are a favored tradition. Men compose and perform songs with playful or suggestive double meanings to woo potential partners. When visiting other villages to perform these songs, they adorn themselves with bright paints, feathers, and ornaments, transforming their appearance into vibrant works of art.

The city of Mount Hagen hosts the annual Mount Hagen Cultural Show, first held in 1961. This event brings together performance groups from dozens of tribes across Papua New Guinea for a friendly celebration of song, dance, and self-decoration. Adornment has long been an art form and a major focus of Melpa creativity, particularly during festivals, cult ceremonies, and moka exchanges. Other artistic expressions include the composition and performance of love songs, laments, ceremonial music, epic chants, and the playing of flutes and Jew’s harps.

As in other parts of Papua New Guinea, rugby is a popular sport around Mount Hagen, with local teams competing against others from across the island. In urban areas, where electricity is available, many residents also enjoy watching television. The country has only one local broadcast station, EMTV, and produces few domestic programs, but satellite television provides access to a wide variety of Australian, British, and American shows.

Melpa Clothes and Body Decoration

Melpa people who live or work in Mount Hagen typically wear Western-style clothing. Men usually dress in shorts, a T-shirt, and a knitted cap, and often carry a bilum, a traditional woven string bag. Shoes are worn when available, though many men go barefoot. Women commonly wear Meri blouses—loose-fitting, A-line dresses made from brightly patterned floral fabric. The Meri blouse was introduced by missionaries in the late 19th century to encourage modesty among women, many of whom traditionally wore only grass skirts. Like men, women carry bilums, though theirs are typically much larger. While some women own shoes, it is far more common to see men wearing them. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Most Melpa own only one change of clothing, and it is still common to see people dressed in traditional attire, especially during ceremonies. Adult men may wear wigs made of human hair for important occasions. Travelers from rural hamlets sometimes arrive by plane at Mount Hagen’s airport in full traditional dress, carrying stone axes and digging sticks—a striking contrast that makes the airport a true meeting point of the jet age and the Stone Age.

Body decoration remains one of the Melpa’s most distinctive art forms. The body is painted with pigments made from local clays and plant dyes mixed with pig fat, and decorated with feathers, shells, and moss. Elaborate headdresses often include bird-of-paradise feathers, parakeet plumes, and modern materials such as product labels or metal can tops. A particularly creative adaptation is the use of Liquid Paper (white correction fluid) as a substitute for traditional white pigment—the brightness of its color makes it highly prized. In the past, moka exchanges were major occasions for such decorative display.

Men’s Ceremonial Outfits feature bird-of-paradise and parakeet feathers, kina shell breastplates, or, when shells are unavailable, crescent-shaped cardboard cutouts fashioned into necklaces. Additional adornments include armbands woven from cane and decorated with fern fronds and mosses. The essential male garment, similar to that of the Huli wigmen, consists of a wide belt (hago) supporting a woven knee-length apron, with a smaller apron covering the genitals. The back is adorned with long cordyline leaves, selected for their shiny red and green hues edged in yellow, and often folded accordion-style. The ensemble is completed with white-painted forearms and calves, a bilum slung over one shoulder, and either a spear or an axe, blending beauty with an aura of readiness for combat.

Women’s Ceremonial Outfits are is equally striking. Women wear mother-of-pearl breastplates, a reminder of the shell currency that served as a major form of wealth in the Highlands until the 1970s. Their headdresses, like the men’s, are adorned with bird-of-paradise and parakeet feathers. Older women may go bare-chested, while younger women sometimes wear bandeaus woven from bilum string or cuscus fur. The lower body is covered with a long grass skirt, tied with a belt at the waist, and overlaid with a colorful apron of cordyline leaves folded accordion-style. Their faces are painted in bold, intimidating designs, meant to inspire fear in enemies. Many also carry ceremonial drums, which they claim are effective for driving away evil spirits.

Melpa Economic Activity

The Melpa are primarily Highlands farmers, traditionally cultivating sweet potatoes as their staple crop. In recent decades, however, coffee has become an important cash crop and a major source of income. Many Melpa now work in urban occupations in Mount Hagen, employed as taxi and bus drivers, airport porters, shop assistants, and in other service roles. The regional government has also identified tourism as a promising sector for economic development within the Melpa homeland. [Source: Andrew Strathern, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Traditional subsistence was based on the cultivation of sweet potatoes, grown in mounds or square plots surrounded by drainage ditches. In fallow areas beneath trees, Melpa farmers also planted cucumbers, beans, maize (a later introduction), sugarcane, and bananas, both for cooking and for eating ripe. Today, many of these gardens have been supplemented or replaced by coffee plantations, which generate income for households. Surplus vegetables are commonly sold at the Mount Hagen market, while trade stores scattered across the countryside offer imported goods such as clothing, packaged food, and household tools.

In precolonial times, the Melpa operated numerous stone-axe quarries, producing rough-cut and polished axes that were both used locally and traded across the Highlands. With the arrival of Europeans, steel tools replaced the traditional stone implements. Archaeologists have also found prehistoric mortars and pestles in the region, though among the Melpa these were venerated as cult objects rather than used as tools.

Over time, Melpa exchange networks extended widely, particularly westward with Enga-speaking peoples, with whom they traded stone axe blades for salt packs. Major religious cults spread into the Melpa area from the south and southwest via Tambul, while the northern lowlands supplied fruit, pandanus, and bird plumes. The moka exchange system linked numerous groups across the region through complex networks of reciprocal obligations, centered on the exchange of pigs and shells between partners. Today, the Melpa remain active participants in both traditional exchange systems and global markets, with coffee serving as their primary export commodity to the world market.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025