Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

KALULI

Kaluli men Tribes of Papua New Guinea

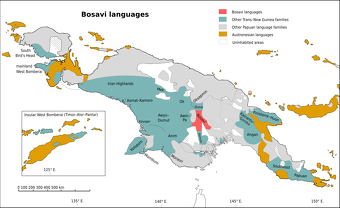

The Kaluli inhabit the dense rainforests surrounding Mount Bosavi, on the Great Papuan Plateau in Papua New Guinea’s Southern Highlands. Also known as the Bosavi, Orogo, Waluli, and Wisaesi, they form one of four closely related Bosavi language-clans, collectively called Bosavi kalu (“men of Bosavi”). Of these, the Kaluli are the most numerous and most extensively documented by anthropologists and missionaries. Although increasingly in contact with the outside world, the Kaluli continue to live much as their ancestors did — cultivating their gardens, hunting in the forest, and preserving a worldview that celebrates the sounds, spirits, and stories of the Bosavi rainforest. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The name Kaluli itself means “real people of Bosavi”. Estimates of their population range from about 2,000 to 4,000, though some sources suggest as many as 12,000. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 3,700. They numbered approximately 2,000 people in 1987 and 1,200 in 1969. Their population declined sharply after epidemics of measles and influenza in the 1940s and has never fully recovered due to continued high infant mortality and periodic outbreaks of disease.

The homeland of the Kaluli lies along the northern slopes of Mount Bosavi, between the Isawa and Bifo rivers at altitudes of about 900 to 1,000 meters (2,950 to 3280 feet). The region is covered by thick rainforest, interlaced with clear streams and home to abundant bird and animal life. Temperatures remain constant year-round, with a long dry season from March to November and torrential rains from December to February.

Kaluli Language is a member of the Bosavi Family of Non-Austronesian languages, which also includes Beami (Gebusi). As of the 1990s, most Kaluli were monolingual, maintaining their ancestral speech and oral traditions.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FLY RIVER PEOPLES — GOGODALA, BOAZI, KIWAI — AND THEIR LIFE, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

KERAKI OF THE TRANS FLY REGION: LIFE, SOCIETY AND SODOMIST INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

NINGERUM PEOPLE OF CENTRAL NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

MOTU — THE PORT MORESBY AREA PEOPLE — AND THEIR HISTORY, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GEBUSI, PURARI, OROKOLO ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

OROKAIVA AND MAISIN PEOPLE OF ORO PROVINCE IN SOUTHEAST PNG ioa.factsanddetails.com

Kaluli History

Physiological and cultural evidence indicates that the Kaluli share closer ties with lowland Papuan groups than with the nearby highland peoples. However, there is no firm evidence suggesting that they originated outside the region they now inhabit. Historically, their trade and cultural exchanges were mainly with groups to the north and west. Over time, the Kaluli gradually moved eastward from their original settlements, advancing deeper into the untouched rainforests. This movement likely reflected both the need for new gardening land and defensive efforts to avoid the expansion of their traditional enemies — the Beami and Etoro — who live to their west and northwest. Although warfare and raiding were once common across the plateau, the Kaluli also maintained enduring trade partnerships with neighboring groups, particularly the Sonia to the west and the Huli from the Papuan Highlands. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The main sources of conflict were the theft of wealth or women and, prior to 1960, acts of retribution for a death. Deaths were believed to result from witchcraft, regardless of the apparent cause. In such cases, the deceased’s close friends and relatives used divination to identify the supposed witch and then organized a raiding party to attack the accused’s longhouse. The raiders would surround the longhouse at night and rush it at dawn with the express purpose of clubbing the witch to death. The body was then cut up and distributed among the kin of the raiding party members. Later, those involved in the raid paid compensation to the witch’s longhouse to prevent further retaliation. Government intervention on the plateau brought an end to retributive raiding and its attendant cannibalism in the 1960s, but it did not establish an alternative means of addressing deaths. Afterward, an accused witch was typically confronted, and compensation was demanded, though there was no effective way to enforce payment.

The first recorded European contact with the Bosavi Plateau occurred in 1935, introducing new materials — most notably steel axes and knives — into local trade networks. World War II temporarily halted Australian exploration in the area, which resumed in 1953. During this period, contact between the Kaluli and Australian administrators became more frequent, and government influence began to extend into local life. By 1960, warfare and cannibalism had been officially suppressed, and in 1964 missionaries constructed an airstrip near Kaluli territory to serve two mission stations established in the region.

Kaluli Religion

Christianity was introduced by missionaries to Kaluli communities in the 1960s and has since spread widely. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 80 percent of Kaluli are Christians, wiith the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent. Even si traditional beliefs continue to play a role in daily life. [Source: Joshua Project]

Spiritually, the Kaluli viewed the visible world as deeply intertwined with an unseen realm inhabited by spirits of the dead, animals, and natural forces. Every person was believed to possess a spirit “shadow” — a wild pig for men and a cassowary for women — whose fate was directly linked to their own. If a shadow was injured or killed, its human counterpart would fall ill or die. Spirit mediums served as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual worlds, conducting séances to communicate with spirits for healing, divination, or guidance. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Kaluli understood the unseen world as a tangible extension of daily life. “All that cannot be seen is a very real part of Kaluli life,” it was said. The dense forest that surrounded them concealed much from view but was alive with sound — the cries of birds, the rustle of animals, and the whispers of spirits. They woke not to the rising sun but to the screech of birds, and they regarded the mournful call of a pigeon as the voice of a lost child calling for its mother. To them, beings unseen were shadows or reflections; when a shadow died, so too did the person it mirrored. The spirits of the dead, along with those who never took human form, inhabited this invisible world. These spirits, often embodied in wild pigs and cassowaries, were not thought to bring harm to the living but instead formed part of a reciprocal balance between both worlds.

The Kaluli believed that the spirit world mirrored the natural one and obeyed the same laws. Within this unseen realm were several kinds of beings: ane kalu (spirits of the dead), who were generally benevolent and could assist the living; mamult, aloof spirit-hunters whose thunderous ceremonies were said to cause seasonal storms; and kalu hungo (“dangerous men”), who inhabited particular streams or sacred places and could bring misfortune to trespassers.

Kaluli Ceremonies and Beliefs About Death

Ceremonial life centered on the Gisaro, a dramatic ritual of music, dance, and emotion performed during major events such as weddings. Visiting dancers, elaborately adorned, sang songs that evoked memories of deceased loved ones and sacred places, stirring deep sorrow in their hosts. When the audience was moved to tears, men from the host longhouse would press burning torches against the dancer’s back — a symbolic act of emotional reciprocity and release. Afterward, the dancers left gifts for their hosts as repayment for their grief. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Spirit Mediums — men who had “married” spirit women in dreams — were considered the most powerful religious practitioners. They were believed capable of leaving their physical bodies to walk in the spirit world, or of allowing spirits to speak through them during trance sessions. Mediums were sought for curing illness, finding lost pigs, or identifying witches. Witches (sei), male or female, were said to be unaware of their dark aspect, which wandered by night to harm others, though it rarely attacked kin. Food taboos and the use of medicinal plants are commonly applied to treat illness, but most curing is done through the assistance of a medium, through actions he takes while traveling in the spirit world. ~

In death, the Kaluli believed that a person’s spirit departed the body and was chased by the longhouse dogs into the forest, eventually reaching the Isawa River — a road leading westward into the afterlife. There, the spirit passed through a place of fire called Imol, where it was burned before being rescued by a spirit of the opposite sex, who carried the soul home and took it as a spouse. From then on, the spirit might appear to the living as a forest creature or communicate through a medium.

Traditional mortuary customs involved displaying the body inside the longhouse, stripped of ornaments and suspended in a woven cane hammock near the women’s communal area. Fires burned at the head and feet as kin and friends paid their respects. Later, the remains were placed on an outdoor platform until decomposition was complete, after which the bones were collected and hung in the eaves of the longhouse. Following government regulations in 1968, burial in cemeteries became mandatory. Mourning included food taboos, strictly observed by close kin — particularly the spouse and children — but often voluntarily adopted by friends and extended family as an expression of shared grief.

Kaluli Family and Marriage

Kaluli marriages have traditionally been exogamous, meaning individuals were expected to marry outside their own clan or community. Their society has traditionally been organized into patrilineal clans, with each longhouse community comprising two or more lineages. Although descent and inheritance have been traced through the male line, individuals also recognized important ties to their mother’s kin. Paternal kinship connected longhouses across tribal boundaries, while maternal kinship established personal relationships between individuals, usually with those they felt closest to — relatives they lived with, grew up alongside, or saw most frequently. The strength of these bonds was often reflected in how much food and garden produce they shared. Inter-village relationships were maintained through marriage alliances, which were matrilineal in their affiliations and helped reinforce social and economic ties. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Kaluli marriages were arranged rather than based on individual choice. Typically, the elders of a prospective groom’s longhouse — led by his father — initiated the match, often without the knowledge of either the young man or the woman involved. Bridewealth negotiations began early, with contributions collected from nearly all members of the groom’s longhouse, regardless of kinship, and distributed similarly within the bride’s community. Ideally, marriages followed the pattern of sister exchange, in which a man’s classificatory sister was offered in marriage to his wife’s classificatory brother, though this ideal was rarely achieved.

The presentation of bridewealth was accompanied by elaborate ceremony, often featuring a Gisaro — a dramatic performance of dance and song by the groom’s kin. Once the exchange was completed, the bride moved to her husband’s longhouse, though conjugal life typically began only after several weeks. Marriage established a lasting bond of mutual obligation, particularly through the exchange of meat between the groom and his in-laws — especially his wife’s father and brothers — a custom that continued throughout married life. Polygyny was permitted but uncommon.

Within the longhouse, each nuclear family functioned as a semi-independent unit, responsible for its own gardening and cooking. Nevertheless, food was freely shared, and the longhouse as a whole operated as a single economic and social community. Inheritance followed the male line: land and sago groves usually passed from father to son, while personal possessions — such as net bags, tools, bows, or ornaments — were given to the surviving spouse, children, or close companions of the deceased.

Child-rearing was primarily the responsibility of women. Mothers, aided by other women and older girls of the longhouse, raised the young children. Girls learned domestic and gardening skills by observing and assisting their mothers, while boys, with fewer early responsibilities, spent their time playing or accompanying older boys on hunting and fishing trips. As boys grew older, they moved from their mother’s sleeping area to the communal hearth at the back of the longhouse, where they listened to men’s stories and learned about adult life.

Kaluli Sexuality

Legends and myths are very important in Kaluli culture. One such myth tells of the mɛmul spirits giving the bau a, a ceremonial hunting lodge for unmarried men, to the Kaluli people. In ancient times, the mɛmul instructed the tribe to seclude the women, which led to a reversal of gender roles. The women hunted while the men stayed in the longhouse and beat sago. However, when the mɛmul saw the consequences of their actions, they changed the bau a into a rite of passage exclusively for males. The Kaluli believe that boys need help to become men, which comes in the form of homosexual intercourse with older bachelors. Girls, on the other hand, are believed to mature naturally. Under the special tutelage of the mɛmul spirits, the bau a acts as the catalyst for this growth-stimulating procedure. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

In adolescence, boys traditionally entered a close relationship with an older man, believed to be essential for their physical and social development into manhood. Before outside contact, young unmarried men from several clans would periodically withdraw into the bau a, or ceremonial hunting lodge, for up to a year. During this seclusion, they hunted daily, learning the terrain, animal behavior, and the knowledge required for adult life. While not a formal initiation, this period served as an intensive training in the ways and responsibilities of Kaluli men.

Edward L Schieffelin wrote: “Homosexual intercourse for boys…took place in everyday life…whenever a boy reached the age of about ten or eleven”... “The growth of young boys who were around the age of puberty was encouraged specifically by pederastic homosexual intercourse [of boys] with some of the bachelors. Kaluli believe that girls attain full maturity as women by natural growth but that boys cannot do so without being given a “boost”, as it were, by the semen of older men. This pederasty was considered a major male secret vis-à-vis the women, and it was generally regarded with embarrassment and lascivious humor among the men themselves. Homosexual intercourse for boys also took place in everyday life beyond the bau a [a major ritual abandoned at the time of writing] context whenever a boy reached the age of about ten or eleven. At that time a father would choose a suitable partner to inseminate him, and the two would meet privately in the forest or a garden house for intercourse over a period of months or years. Less frequently a boy might choose his own inseminator, although this was risky: if the man was a witch, his semen would the boy into one too. In the bau a, the boys were inseminated “openly” (that is, they were inseminated by their homosexual partner after lights out in the close, crowded, smoky darkness of the bau a while the rest of the exhausted hunters were thought to be asleep). A few bachelors came to the bau a specifically to act as inseminators, and fathers sometimes assigned their sons to one or the other of them. Other lads chose their own inseminators from among the older bachelors (or bachelors chose them) and formed specific liaisons for a while. Side by side with the serious business of hunters, pederastic intercourse was a marked feature of the bau a which men chuckled over self-consciously in reminiscence”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Last revised: Jan 2005, Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

A heterosexual virginity was expected to be able to enter bau a (‘measured’ by means of a practical joke); in fact, an imminent heterosexual affair of a bachelor might precipitate the organisation of a bau a. Ayasilo (bau a officials) do not engage in homosexual activity, since it is considered “ultimately profane in Kaluli belief because it is sexual” (ibid., p172). Loss of innocence, thought to negatively impact hunting skills, is not one of knowledge, but of (heterosexual) social entanglement. Non-ritualized, profane and impure homosexual activity occupies a nexus in-between defiling heterosexual intercourse, and the ideal of celibacy as assigned to ritual officials.

Kaluli Society

Kaluli society is highly egalitarian, with no formal leadership or “Big Man” system. Elders and wealthy men—especially longhouse owners or ceremony sponsors—hold greater influence, but any adult male may lead group action if he can rally support. Authority rests on experience, generosity, and resourcefulness rather than rank. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The longhouse is the central unit of social, economic, and ritual life, taking precedence over clan or lineage. Longhouses are linked through marriage exchanges, kinship ties, and reciprocal gift relationships that ensure hospitality and support between communities. Social control depends on informal sanctions such as gossip, ridicule, or demands for compensation. Serious transgressions were once deterred by the threat of retaliatory raids, now forbidden by the government. Beliefs in spirits also reinforce moral behavior, especially through food taboos.

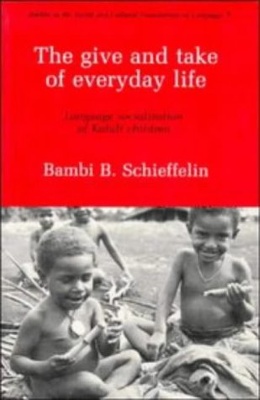

Linguistic anthropologist Bambi Schieffelin has shown that Kaluli socialization centers on communication: children learn to become competent members of society through repetitive, interactive exchanges with elders, reflecting the culture’s emphasis on cooperation and shared understanding.

Kinship and Land: The Kaluli are patrilineal and exogamous, tracing descent through the male line while maintaining valued ties to maternal kin. Kinship terms emphasize siblings and classificatory cousins rather than strict genealogy. Marriages are arranged by elders and involve bridewealth payments of food and goods from the groom’s kin to the bride’s family. Land—mainly gardens and sago stands—is individually owned by men and passed from father to son; unused plots eventually revert to communal claim.

Kaluli Life

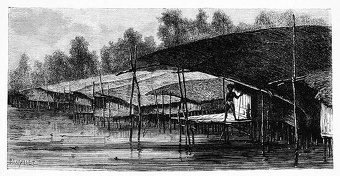

Kaluli communities are centered around large longhouses (See Below). These communal buildings serve as both homes and social centers, symbolizing unity and clan identity. Inside, sleeping areas are divided for men, women, and families, with a central hall for cooking, meetings, and ceremonies. Surrounding each longhouse are gardens and small shelters used by visitors or during harvests. Although smaller individual houses are now more common, the longhouse remains the heart of Kaluli life—a place for working, eating, singing, and sharing together. [Source: Wikipedia, Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The sago palm is a dietary staple. Its pith is laboriously extracted, mashed, and cooked into a dense, pancake-like food that provides most of the community’s daily sustenance. The Kaluli are deeply attuned to their landscape, giving unique names to trees, rivers, and streams. They practice swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture and rely heavily on forest resources. Fish, crayfish, rodents, and lizards form their main sources of protein, supplemented by a few domesticated pigs.

Kaluli life is marked by a strong emphasis on verbal interaction. Speech is the main medium for expressing thought, desire, and emotion, and linguistic skill is a measure of social competence. Socialization into speech begins only after a child shows intentional use of words—for example, when first saying “mother” or “breast.” Before this, infants are not treated as intentional beings, unlike in many Western cultures where adults address babies directly with simplified “baby talk.”

Food and speech together sustain the fabric of Kaluli relationships. Sharing food is a key expression of affection and obligation: hosts are expected to feed visiting kin, and withholding food leaves one in “social limbo.” Hospitality reaches its peak during ceremonies, when longhouses host others with elaborate feasts. Hosts present food but do not eat, symbolizing generosity and respect. On a more personal level, close friends may share a meal of meat and affectionately address each other by the name of the food—such as “my bandicoot”—as a sign of deep mutual regard.

There is division of labor between men and women. Men work collectively to fell and process sago palms, clear gardens, build fences and dams, hunt large game, and perform rituals associated with garden fertility. Women process sago pith, weed gardens, tend pigs, gather small forest animals and crayfish, cook, and care for children. Cooperation and reciprocity are essential to maintaining both economic and social balance.

Kaluli Clothes and Adornment

The traditional dress of the Kaluli tribe is a striking representation of their culture and identity. Each element of their attire holds deep cultural significance, handed down through generations as a symbol of their heritage. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea]

Bilas is the traditional body decoration that plays a central role in Kaluli ceremonies and rituals. It encompasses various forms of adornment, such as body paint, feathers, shells, and ornaments made from natural materials found in the surrounding forest.

Kaluli men in ceremonial clothes Tribes of Papua New Guinea

The process of applying bilas is an art form in itself. Elaborate designs are painted on the body, using natural pigments sourced from plants and minerals. Red ochre, derived from iron-rich soils, symbolizes strength and vitality, while black charcoal represents transformation and spiritual power. White clay, obtained from nearby riverbeds, signifies purity and connection to the spirit world.

Feathers and shells are meticulously arranged to create stunning headdresses and necklaces, reflecting the Kaluli’s reverence for the animals and spirits of the jungle. Feathers of vibrant colors are attached to bamboo frames, which are then adorned with shells and other natural embellishments, invoking a sense of awe and wonder.

Bilum is a hand-woven bag carried by both men and women. The bilum serves as a practical item, used for carrying food, tools, and personal belongings. However, its significance extends far beyond mere functionality. The intricate patterns and colors of the bilum are a reflection of the weaver’s artistic expression and cultural identity. Each design tells a unique story, passed down through generations, carrying the collective memory of the Kaluli people. Weaving is a skill acquired from an early age, and the creation of a bilum is a labor of love, often taking weeks or even months to complete.

Headdresses hold a sacred place in Kaluli culture, serving as powerful symbols of spiritual connection and protection. The headdresses worn during ceremonial events are often adorned with feathers, shells, and other mystical elements, representing the mɛmul spirits and the forces of nature. In the bau a, young boys wear distinctive headdresses made from feathers of various bird species found in the jungle. These feathers are believed to harness the strength and qualities of the animals, empowering the boys on their journey to manhood.

Kaluli Villages and Longhouses

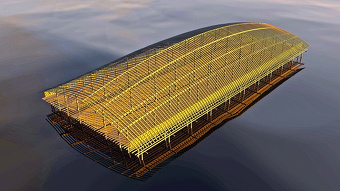

Architectural design graphic of a Kaluli longhouse Dennis Holloway architect

The Kaluli live in about twenty autonomous longhouse communities, each home to roughly fifteen families—or about sixty people. Each settlement centers on a large elevated longhouse, about 18 by 9 meters (60 by 30 feet), built five to twelve feet above the ground with verandas at both ends. The longhouse functions as both dwelling and social hub—a place where residents work, cook, sing, and hold meetings together. Surrounding it are gardens, fruit trees, and small shelters for guests or temporary use during harvests. [Source: Wikipedia, Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Inside, the longhouse is divided lengthwise by a central hall. Married men’s sleeping platforms alternate with cooking hearths and meat-smoking racks, while women’s platforms line the outer walls, separated by partitions from their husbands’. Young children sleep with their mothers, older boys with bachelors at the rear, and unmarried women together at the front. Fireboxes allow for smaller meals, but the hall serves as the community’s gathering space for shared meals, discussions, and ceremonies.

Pigs live beneath or around the longhouse, serving as both livestock and “watchdogs” whose noise alerts residents to intruders. When a man marries, his longhouse companions contribute to the bridewealth. Every two to three years, as the longhouse deteriorates, the community relocates and builds anew in a nearby area.

Longhouses are more than dwellings—they symbolize clan identity and connection to the land. Their names are used socially to signal belonging and, historically, as markers of territory during conflict. Although some families now live in smaller separate houses, the longhouse remains the spiritual and social center of Kaluli life.

Kaluli Agriculture and Economic Activity

The Kaluli subsist on a mixed economy of sago extraction, gardening, hunting, and fishing. Sago, harvested from self-propagating palms in the forest, is their staple food and is supplemented by garden crops such as bananas, taro, sweet potatoes, pandanus, breadfruit, pitpit, and sugarcane. Protein is obtained from wild game, lizards, fish, and crayfish. Pigs are domesticated but reserved for ceremonial occasions, where pork—along with grubs incubated in sago palms—plays a vital role in feasting and gift exchange. The sharing of food lies at the heart of Kaluli social life, expressing generosity, respect, and the bonds between kin and neighboring communities. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Kaluli craft production is modest but resourceful. They make digging sticks, stone adzes (now often replaced by steel tools), black-palm bows, and woven net bags (bilum). Forest materials provide everything from construction timber to ceremonial decorations. The most elaborate items are the ornate costumes and headdresses worn during rituals.

Trade occurs both within and between Kaluli longhouse communities through a network of reciprocal gift exchange. Locally produced goods such as bows, net bags, and stone tools are exchanged for items from neighboring groups—hornbill beaks and dogs’ teeth from the west, tree oil from the south, and salt, tobacco, and woven aprons from the highland Huli. This circulation of goods reinforces social relationships and connects the Kaluli to the wider regional trade system.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025