Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

SIMBARI

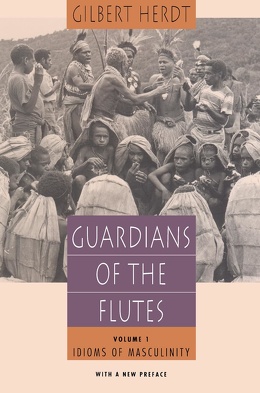

The Simbari people are a mountain-dwelling, hunting and farming people who inhabit the fringes of the Eastern Highlands. Also known as the Chimbari, Anga and Sambia, they are a mix of historically and socially integrated kinship groups that speak the Simbari language and have traditionally been animistic. Simbari culture and society have been studied extensively by Gilbert Herdt, who called them the Sambia, and other anthropologists. The name Sambia comes from the Sambia clan, one of the original groups to settle the central Sambia region in the Puruya River Valley. The term is mainly used by Westerners. The derogatory name “Kukukuku” was broadly applied to the Simbari and their neighbors until the 1970s. The word “Anga”, meaning “house,” has since been used as an ethnic label for the Simbari and related peoples. [Source: Gilbert Herdt, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, Wikipedia]

The Simbari have traditionally inhabited the rugged Kratke Mountains, bordered by the Lamari River, the Papuan lowlands, and adjacent valleys of the Eastern Highlands Province (Marawaka District). Roughly two-thirds of their land remains covered in virgin rainforest. Settlements and gardens are found at elevations between 1,000 and 2,000 meters (3,900–7,800 feet), while hunting grounds reach up to 3,000 meters (11,600 feet).

According to the Joshua Project, the Simbari numbered about 9,000 in the early 2020s, with 99 percent identifying as Christian. In 1989, their population was estimated at 2,700, including absentee coastal workers. At that time population density averaged 1.5 persons per square kilometer, though settlement areas were more concentrated, and the annual growth rate was around 5 percent. Also at that time, Sambia-speaking people made up about 95 percent of residents, alongside small numbers of in-marrying Fore and Baruya speakers, and about 3 percent Tok Pisin speakers from other parts of New Guinea, mainly employed in government or mission work.

: Language: The Simbari language (also known as Chimbari or Sambia) is an Angan language within the Trans–New Guinea family. It is closely related to neighboring Angan languages of the Papuan Gulf. The Simbari and the Baruya share about 60 percent of their vocabulary, though most speakers are not mutually intelligible. There are two main dialects—northern and southern—within central Sambia. These dialects are mutually intelligible, differing slightly in vocabulary and tone.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Simbari History

The exact origins of the Simbari and related Angan peoples are unknown, though they were believed to have migrated south toward the Papuan Gulf and later—perhaps as recently as A.D. 1700—to their present territory. Their mythological place of origin was said to lie near Menyamya. Both legend and historical evidence suggested a long history of endemic warfare and raiding between the Simbari and neighboring tribes, especially the Fore and Baruya. [Source: Gilbert Herdt, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, Wikipedia]

Warfare was organized mainly at the village level, though dance-ground confederacies—alliances of villages that initiated together—were especially significant. These confederacies defended each other’s territories, intermarried, and often consisted of single kinship groups, though multi-kin confederacies also existed in central Sambia. The national government provided schools, courts, and health services. Traditionally, minor disputes within villages were resolved through discussion, while warfare between communities arose over adultery, sorcery accusations, ritual violations, theft of ritual items, or damage to gardens by pigs. In later years, such conflicts were settled by councillors and district courts. Most aspects of social control rested with clan and hamlet elders, while war leaders played a key role in times of conflict. Ritual initiation instilled values of conformity and loyalty, and dance-ground confederacies maintained order in intertribal relations.

Initial contact with Europeans began around 1956, when Australian government patrols first entered the area. Under a United Nations mandate, the Australian colonial administration gradually enforced pacification, which was largely achieved by 1963. Warfare ceased in 1967, and the following year the Simbari region was “derestricted” and opened to Western missionaries and traders. Coffee was introduced as a cash crop around 1970. A short-lived headman system, modeled after African colonial administrations, was replaced in 1973 with komiti and kaunsal (councillors) freely elected to a district government council. Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975 marked the beginning of rapid modernization efforts.

In 2006, anthropologist Gilbert Herdt updated his studies in “The Simbari: Ritual, Sexuality, and Change in Papua New Guinea”, documenting the gradual decline and eventual disappearance of traditional rituals. Several factors contributed to this transformation. The Australian government’s suppression of intertribal warfare in the 1960s profoundly altered male identity and disrupted the warrior ethos that had long underpinned initiation ceremonies. Beginning in the late 1960s, migration also played a role, as men left the highlands to work on coastal cocoa, copra, and rubber plantations, exposing them to the outside world and its influences—money, alcohol, fast food, and sex with female sex workers.

Schools, both governmental and missionary, were introduced into the Simbari Valley during the 1970s. Herdt observed, “schools began to displace initiation as a primary means for gaining access to valued positions within the expanding society.” Increased contact with the outside world brought material goods, which undermined the local economy and traditional masculinity—no longer tied to the making of local products such as bows and arrows. Christian missions further accelerated these changes through the introduction of foreign foods and material items as well as education.Missionaries denounced shamans, polygyny, and male initiation rites, shaming elders who upheld these customs. Among the Simbari, Seventh-day Adventist missionaries became especially influential, introducing Levitical dietary restrictions that forbade the consumption of pigs and possums, key sources of food and prestige. As a result, hunting, one of the central social and political activities of Simbari men, was largely abandoned among Adventist converts.

Simbari Religion

Simbari in 2010 New Tribes Mission

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Simbari are 99 percent Christian. They were traditionally animistic, believing that all forces and events possessed life. Men were regarded as superior and women as inferior, and female menstrual and birth pollution were deeply abhorred. Male maturation was thought to require homoerotic insemination to achieve biological competence. Consequently, initiation rituals involved complex homosexual contact from late childhood until marriage, when such practices ceased. Female homosexual activity was believed to be nonexistent. Men’s ritual cult ceremonies centered on flute spirits, which were considered female. Other supernatural beings included ghosts, forest spirits (male), and nature sprites; for example, bogs were believed to be inhabited by ghosts and sprites. [Source: Gilbert Herdt, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Ritual and the men’s secret society were once the key cultural forces in Simbari life. Initiations occurred on a grand scale every three or four years and were mandatory for all males. Female initiations took place later, at marriage, menarche, and first birth. Male initiation also served as military training for warriorhood. The ceremonial calendar followed a cyclical sense of time, with ritual events and feast gardens coordinated with the dry and early monsoon seasons (May–September).

Each village had at least one senior ritual specialist who officiated at initiations. The main religious figures, however, were shamans, who could be either male or female, though men were traditionally more common and more influential. Illness was believed to result from ghosts or sorcery, and possession was attributed to spirits of the dead or forest beings. Local healers and shamans treated these afflictions using spells and herbal medicines, especially ginger and local salt. Shamans divined, exorcised, practiced sorcery, and were believed to retrieve the souls of the sick through magical flight. They organized rituals and funeral ceremonies, and were categorized as strong or weak depending on their power.

Funerals were traditionally simple ceremonial affairs. The corpse was placed on a platform until the bones were exposed, after which the bones were kept by close kin for their sorcery power. The soul was believed to survive death and could be seen in dreams. The widow observed a year or two of mourning. In later times, the corpse was buried, though a name taboo for the deceased continued for several years.

The introduction of Christianity in the 1960s and 70s had a profound impact on the Simbari. Mission activities focused mainly on the local Seventh-day Adventist church, where daily and Saturday services were held, and baptisms and marriages were performed. Missionaries denounced shamans, polygyny, and male initiation rites, shaming elders who preserved these practices (See History Above). Most missionized Simbari remained nominal converts in the 1990s.

Simbari Family, Marriage, Kinship and Society

Simbari family in 2010 New Tribes Mission

The nuclear family has traditionally been the minimal Simbari domestic unit, with family members eating and sleeping together. In the past, sons remained at home until initiation, while daughters stayed until marriage. The extended family included grandparents, grandchildren, aunts, uncles, and cousins, usually living within the same village. All adults contributed to domestic labor, and children assisted as well. Co-wives sometimes lived together, though each typically had her own residence. Infant care was carried out exclusively by women, while older children were cared for by both parents and siblings. Independence and autonomy were valued—especially for males. Gender and sexual socialization were achieved mainly through ritual. Property was inherited primarily by men, though daughters held use rights to certain garden lands. Status and offices were achieved rather than inherited, except for the mystical powers of shamans, which were believed to be passed down. [Source: Gilbert Herdt, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

There were four main types of marriage: infant betrothal (delayed exchange), sister exchange (direct exchange), and bride-service (delayed exchange)—all traditional forms—and bride-wealth marriage, introduced after 1973. Marriages were usually arranged by parents and clan elders. Because of exogamy (marrying outside the village or clan), intravillage marriages were rare in pioneer settlements but more common in consolidated ones. Traditionally, infant betrothal and sister exchange accounted for about 90 percent of marriages. Father’s sister’s daughter marriage was approved. Newlyweds established patrilocal residence, building a new hut near the husband’s kin. Divorce was rare, and polygyny, though idealized, was infrequent.

Kinship operated on three levels. The clan, based on patrilineal descent, was exogamous. Two or more clans formed a “great clan,” tracing descent to a shared ancestor. Multiple clans and great clans together made up a larger kin group, whose ancestral “brothers” linked them through shared territory, dress, and rituals. These groups intermarried, supported each other in warfare, and conducted joint initiations for their sons. Land and watercourses were held collectively by individuals and clans. Hunting, gardening, fishing, and foraging rights were strictly protected, though use rights could be extended to in-laws, distant kin, or trade partners. Landlessness did not exist. Simbari kin terms followed the Omaha system, characterized by generational merging—fathers and their brothers shared one term, as did mothers and their sisters. Age grading in male initiation also created fictive kinship, treating initiates as “brothers” and females of the same age group as “sisters.”

Simbari society traditionally lacked centralized political leadership or formal hierarchy. Status was based on age and sex: elders, warriors, and ritual specialists held the highest rank, while men ranked above women. Social class was absent, though modernization, wealth, and education later began to introduce class distinctions. By the 1990s, the Simbari were an encapsulated, semi-autonomous tribal group within the bureaucratic framework of Papua New Guinea’s parliamentary democracy, with political organization operated through provincial and district administration. The Simbari area was divided into census divisions, and adult men paid a head tax. The village remained the central political unit in daily affairs, while local councillors managed administration and dispute settlement.

Simbari Initiations

The Simbari people traditionally believed that strict gender roles were necessary to maintain social and spiritual balance. Relationships between men and women were governed by numerous rules and restrictions, reflecting the belief that female bodily processes, especially menstruation and childbirth, carried powerful and potentially dangerous forces. Because of this, boys were separated from their mothers at an early age to limit female influence and to initiate their transformation into men. [Source: Wikipedia]

From childhood through adolescence, males underwent a series of ritualized initiation stages designed to cultivate strength, discipline, and masculine identity. These rites symbolically purified boys of maternal influence and prepared them for adult responsibilities, marriage, and warriorhood. Each stage involved specific teachings about gender roles, social duties, and sexual conduct, reinforcing ideals of male solidarity and control over reproduction and exchange between the sexes.

The initiation process was divided into several major stages: 1) Maku, the first stage, marked the boy’s separation from his mother and entry into the male community. 2) Imbutu emphasized group bonding and discipline, rewarding endurance and cooperation. 3) Ipmangwi corresponded with puberty, when initiates were instructed in adult social and marital roles. 4) Nupusha involved marriage and the assumption of adult male status. 5) Taiketnyi and Moondung marked the transition to fatherhood, symbolizing full social maturity.

Women also underwent rituals marking menarche, marriage, and childbirth, which acknowledged their reproductive power while simultaneously restricting contact with men during periods of perceived heightened spiritual potency. Dr. Birgitta Stolpe worked among the Simbari on female development and menarche in particular. By the late twentieth century, missionary activity, government regulation, and social change had led to the decline and eventual abandonment of these traditional initiation practices.

"Semen Drinking" in Simbari Initiations

The Simbari (Sambia) are known in cultural anthropology circles for their former practice of ritualized homosexuality and semen ingestion rituals among adolescent boys. These practices were rooted in the belief that semen was a vital substance necessary for male growth and maturation. Participation in such rituals was a required stage in the traditional male initiation sequence and did not determine adult sexual orientation. Most men later transitioned to heterosexual marriage once initiation restrictions were lifted. A small minority of males, however, remained unmarried and continued same-sex relations, a behavior regarded as atypical and often ridiculed by other men. item in this spectrum. It was also believed that early heterosexual fellatio “ostensibly precipitates menarche in girls”. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to “Growing Up Sexually”: Since 1977, Gilbert Herdt covered the phenomenon of “Sambia” prepubertal insemination in many works. Many tribes have attributed certain powers to semen, and the onset of puberty is one example. Herdt said: “Men perceive premenarche females as children, a category of asexual or not exciting erotic objects”, in contrast to boys. However, premenarchic coitus is considered dangerous because it would prevent the body from expelling lethal fluids at (naturally timed) menarche. Apart from this, the “Sambia” value male-virgin contacts, while “sexual partners are perceived as having more “heat” and being more exciting the younger they are. A second factor is reciprocity: the more asymmetrical the sexual partners (youth/boy), the more erotic play seems to culturally define their contact” [Source: D. F. Janssen, “Growing Up Sexually”, Volume I. World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin

Against the background of an utterly phallocentric ideology on the androtrophic properties of semen, “Sambia” prepubertal boys (7-12, on average 8.5) fellate post-pubertal adolescents to ejaculation in order to grow and turn seminarchic themselves, so that they may reverse roles. The boys do not have orgasms, and might have “vicarious erotic pleasure as indicated by erections” only “near puberty”. Herdt had argued that this age is “psychologically necessary for the radical resocialization into, and eventual sex-role dramatization expected of, adult men”.

Herdt said that “all sex play is forbidden”, and that sexes are separated from age 5. If sex play should occur, “they would have no thought of being warriors or making gardens, according to the males. Thus, “boys would be polluted and their growth blocked by sexual play with girls”. This script is said to have been successfully enforced. An informant told Herdt that boys are feared for sexual intercourse with women by men. Thus, the boys, who are married to premenarchal girls after the signs of puberty (ages 14-16), are fellated by the wives until these are menarchal; then, coitus takes place. Girls practice fellatio on their adolescent spouses until menarche, and coitus thereafter.

Decline and End of Simbari Initiations

In 2006, “Simbari: Ritual, Sexuality, and Change in Papua New Guinea” Herdt observed that a sexual revolution had transformed the community over the previous decade. He wrote, “To go from absolute gender segregation and arranged marriages, with universal ritual initiation that controlled sexual and gender development and imposed the radical practice of boy insemination, to abandoning initiation, seeing adolescent boys and girls kiss and hold hands in public, arranging their own marriages, and building square houses with one bed for the newlyweds, as the Simbari have done, is revolutionary.” [Source: Wikipedia]

Several forces contributed to the gradual decline and eventual disappearance of traditional initiation and sexual practices. In the 1960s, the Australian government’s suppression of tribal warfare dismantled the warrior ethos (See History above) and labor migration exposed Simbari men to Western sexual norms. Over time, these experiences encouraged new ideas of romance and partnership based on equality rather than hierarchy. Coeducational schooling elevated the social position of women and, for the first time, brought unmarried boys and girls together in close daily contact. These developments, combined with broader economic and cultural shifts—including the rise of coffee cultivation—led to increasing cooperation between men and women, which Herdt described as “perhaps the first time in Simbari history that gender cooperation has been attempted.”

By the 1990s, these transformations culminated in the emergence of what Herdt termed the “Love Marriage,” in which young people chose their own partners freely. Traditional practices of forced separation, ritualized homoerotic initiation, and arranged marriage had largely disappeared by this time, marking a profound redefinition of Simbari sexuality and gender relations.

Simbari Villages and Daily Life

Simbari in 2010 New Tribes Mission

Simbari villages have traditionally ranged in size from about 40 to 250 people, and all were spatially distinct. There were two main types: pioneering and consolidated. Pioneering villages were built on steep mountain ridges, fortified with palisades and fences for defense. Each typically contained a great clan and its component clans, with surrounding gardens and shared hunting and gathering territories. Consolidated villages arose when two previously separate settlements united into a larger, less clustered community. [Source: Gilbert Herdt, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Houses were built in neat rows along the ridges, connected by footpaths to gardens above and streams or rivers below. Each nuclear family lived in its own hut, though extended family members sometimes shared the space. Houses were small, gabled, and thatched, with a hearth and no windows. Two other important buildings were the menstrual hut, located below the village and used for childbirth, menstruation, and women’s ceremonies, and the men’s house, where males lived after initiation (around ages 7–10) until marriage (in their late teens or early twenties). The men’s house served as a military and ritual clubhouse. Both men’s and menstrual houses were taboo to the opposite sex. Casual shelters were erected in gardens as needed, and more permanent lodges for pig-herding and hunting were built in distant gardens and forests, where families sometimes resided for months.

The division of labor was strict and highly gendered. Women handled most gardening, weaving, cooking, and child care, while men hunted, fished, and managed warfare and public affairs. Apart from house construction, most domestic work was performed by women. Men and women shared in harvesting feast crops and, more recently, coffee gardens.

The ritual cult house represented the most elaborate architecture, though it was not maintained after initiation. Carving was limited to tools and weapons, but body painting in rituals and warfare was elaborate, and feather headdresses were prized. Traditional instruments included ritual flutes, bullroarers, and the Jew’s harp, and dancing was extensive though simple, forming a key part of initiations.

Simbari Agriculture and Economic Activity

Sedentary gardening dominated the Simbari economy, supplemented by modest pig herding and, traditionally, extensive hunting by men. Sweet potatoes were the main staple, while taro was also important. Yams were a seasonal and largely ceremonial crop. All planting and harvesting were done by hand, primarily by women, though men cleared the land through slash-and-burn and helped with harvesting. Coffee eventually became the main commercial crop, alongside smaller amounts of chilies. [Source: Gilbert Herdt, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Other traditional crops included sugarcane, pandanus fruit and nuts, wild taro and yams, and various local greens, palms, and bamboo hearts. Over time, European vegetables such as green beans, corn, tapioca, potatoes, tomatoes, and peanuts became common. Traditional hunting focused on opossums, marsupials, birds, and cassowaries, while fishing for freshwater carp and eels was occasional. Meat was often smoked for preservation and trade. In addition to pigs, dogs and chickens were also kept as domestic animals.

Craft specialization was limited, with no true industrial arts. Women wove grass skirts and string bags, while men made armbands, headbands, bows, arrows, and other military gear. Sacred art was rare, and masks or carvings were not produced.

Traditionally, vegetable salt bars, bark capes, feather headdresses, and dried meats and fish were traded with neighboring tribes such as the Wantukiu and Usurumpia, and even as far south as the Purari Delta. In more recent times, women sold homegrown produce in local markets.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025