Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

ENGA

The Enga are one of the largest groups in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea. There are over 500,000 people living in the rugged Enga Province, most of them Enga. Engan society has traditionally been structured around clans and kinship ties. The Enga practice subsistence farming of sweet potatoes, and pigs, culturally valued items used in elaborate exchange systems known as tee. Enga men are known for their distinct body painting, often using black paint to symbolize strength and identity.

The Enga are divided into three subgroups, the Mae, the Raiapu, and the Kyaka. Mae Enga are also known as Western Central Enga The Melpa to the east first called them Enga. This name was adopted European explorers and later by the Enga themselves. One of the more easily recognized Engan tribes is the Suli Muli known for their use of black face paint.

History: Archaeological research in the Central Highlands indicates that horticulturalists were active in the Enga area at least 2,000 years ago and possibly much earlier. These pre-Ipomoean cultivators were presumably the ancestors of present-day Enga people, but their place of origin is unknown. Ipomoea is a large and diverse group of plants that include morning glory, water spinach and sweet potatoes. For centuries, Enga maintained social contacts with non-Enga neighbors, such as through marriage, shared rituals, economic exchanges, and raiding. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Enga first encountered European gold prospectors in 1930 and field officers of the Australian colonial administration in 1938. By 1948, the Wabag subdistrict headquarters had been established, and the government had permitted miners and Christian missionaries to enter the area. Between 1963 and 1973, the administration established six elected local government councils. In 1973, these councils comprised a district-wide Area Authority. In 1964, Enga, along with other residents of the Territory of Papua New Guinea, elected representatives to the new House of Assembly. This assembly became the National Parliament in 1975, after the country secured political independence from Australia. Enga Province was proclaimed in 1974, and a provincial assembly and government were elected in 1978.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

TRIBES OF THE SOUTHEAST NEW GUINEA HIGHLANDS: MAFULU, TAUADE, GOILALA, FUYUGE ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Enga Province

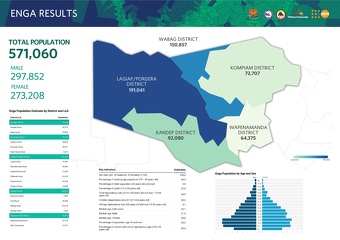

Enga Province covers approximately 11,800 square kilometers (4,556 square miles). The the 2021 Census recorded a population in the province of 571,060 people. Enga Province is divided into six districts: Wapenamanda, Wabag (the capital city), Kompiam, Porgera, Kandep, and Laiagam. Wabag, the administrative center of Enga Province, is situated at about 5°30 S and 143°45 E. Enga Province, one of seven provinces of the Highlands region of Papua New Guinea, is the second most rugged province after Chimbu. Even other Highlanders refer to Engans as true “mountain people”.

Enga Province is very unique. Unlike other provinces in Papua New Guinea, which are occupied by speakers of a myriad of languages, the Enga region has only one major ethnic group and one language, both of which share the same name as the region. The Enga live in river valleys and on mountain slopes between about 1,820 and 2,700 meters (5,970 to 8,860 feet) above sea level. Forested high ridges are uninhabited. The Mean annual rainfall is about 300 centimeters (118 inches), varying between 228 and 320 centimeters (90 and 126 inches). Rain falls about 265 days a year, but there is a summer wet season (November to April) and a winter dry season (May to October). Winter droughts may occur, and at altitudes above 2,500 meters, winter frosts are common; both may cause food shortages. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Situated at the northernmost tip of the Highlands, Enga province is located north and east of the Southern Highlands province and comprises the western half of the central plateaus in west-central Papua New Guinea. It was separated from the Western Highlands district in 1973 and established as a province in 1978. Enga is bordered by the provinces of East Sepik to the north, Madang to the northeast, and Western Highlands to the east. The province consists of rugged mountains and high-altitude valleys. The Schrader Range rises in the northeast, and Mount Hagen, in the southeast, reaches 3,777 meters (12,392 feet) in height. Enga is drained by rapidly flowing rivers; the main ones are the Lai and Lagaip. The landscape is marked by wide swaths burned through the forest by Papuan hunters searching for small game. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica]

In 1960 the then Wabag Subdistrict covered about 8,710 square kilometers and supported an indigenous Population estimated at 115,000, of whom about 30,000 were Mae . Central Enga population densities ranged from about 19 to 115 persons per square kilometer. By the mid-1980s the population of Enga Province exceeded 175,000, including at least 45,000 Mae, and population densities were generally higher.

Enga Language

From SIL-PNG

The Enga people speak Enga, a language which belongs to the West-Central Family of the Central Highlands group of Papuan languages. It is spoken by over 250,000 people, primarily in Enga Province. Enga has the largest number of speakers of any Trans–New Guinea language and the largest number of speakers of any native language in New Guinea. It is second only to Papuan Malay overall. Speakers of Arafundi languages use an Enga-based pidgin. [Source: Wikipedia]

Enga is a predominantly suffixing language. The basic word order is subject–object–verb (SOV). Enga verbs play a central role in the language's syntax, exhibiting highly complex morphology. Enga verbs convey ideas of subordination or coordination, which in Indo-European languages are often indicated by conjunctions, such as "and" or "because." Enga verbs also express different types of modality, such as ability, possibility, or need, as well as interrogation via suffix. In regard to verb tenses, there are: 1) the immediate past, which refers to actions that occurred within the day; 2) the near past, which refers to actions that occurred the previous day or to a time that the speaker does not recall, or a time before the previous day, when the speaker intends to compare it to other events in the past; and 3) the far past, which refers to actions that occurred before the previous day.

Enga is an exclusively suffixing language, meaning it only uses suffixes to form nouns. These suffixes generally appear at the end of a noun phrase and function as either a determiner or an adjective. Enga also includes conditional suffixes. These distinguish between "real" and "irreal" conditions. A real condition is one in which real consequences can occur, as opposed to an irreal condition, which denies the reality of the expressed actions and their consequences. Enga verbs inflect for person, number, and tense-aspect. There are five tense-aspect categories and three grammatical numbers in Enga. Tense-aspects include a future tense, a present tense, and three past tenses. The numbers are singular, plural, and dual, expressed via the prefix na-.

Enga Religion

Many Enga are now Christians. Their traditional religious and magical beliefs, like those of other Central Enga, remain strongly clan-based despite Christian influence since 1948. The Mae believe the sun and moon — “the father and mother of us all” — produced immortal sky beings organized, like the Enga, into patrilineal clans of cultivators. Each celestial kinship group sent a founder to earth, who settled, married, and divided land among his sons. Their descendants formed the present clans, each occupying inherited territory and guarding fertility stones brought by the founding ancestor. Buried in sacred groves, these stones house the spirits of the clan’s forebears, linking living members to their ancestral land. Mae also speak of malevolent ghosts, man-eating demons, and giant pythons that defend the forests and mountains. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Raiapu of Enga believe in a variety of supernatural beings, but, according to anthropologist Richard Feachem, they "derive no joy or comfort from their religious beliefs" due to the indifferent or malevolent nature of those spirits. The Yalyakali, or "Sky People," are fair-skinned, beautiful deities whose idyllic lives in the clouds mirror the agricultural and clan structure of the Raiapu people below, but without the sadness of ordinary life. They are considered remote and unapproachable by humans. According to Feachem, the remaining spirit beings (ghosts and demons) are an aggressive and bellicose group engaged in an endless cycle of revenge and mischief. The Yuumi Nenge, or "destructive ground force," are ghosts that cause deaths by exposure in the forest. [Source: Wikipedia]

A Timongo is a spirit that leaves a human body upon death and wanders the forests, serving as "a continual source of fear and alarm for the living," especially for the living members of their immediate families. They bear "bitter grievances" against these family members. Evil, carnivorous demons known as “pututuli” also live in the wild forests, as well as in caves and pools. They can change their shape, but are often seen as extremely tall beings with two-fingered claws. The Raiapu believe that female demons occasionally switch human babies with putuli babies.

Death, whether by violence or disease, is usually blamed on ghosts, less often on sorcery or demons. Funerals involve simple burials, mourning, and feasts with exchanges of pigs and valuables. The spirit of the dead is expected to take vengeance on a family member before joining the ancestral spirits of the clan.

Topoli are human sorcerers who possess secret knowledge of spells and other esoteric information. They can defend themselves against hostile spirits and communicate with them. Feachem writes that they "may be described as a healer of broken limbs or a catcher of lost ghosts." While lethal sorcery is rare, men commonly use magic for health, wealth, and success in war. Young bachelors undergo secluded cleansing rituals to remove the dangers of contact with women, followed by clan feasts marking their return. Women perform purification rites after menstruation or childbirth and use charms to protect gardens. After illness or death, a medium or diviner identifies the offended spirit, and the family head sacrifices pigs to appease it. Major disasters — defeat, famine, or epidemic — lead clans to offer large feasts and decorate the fertility stones to restore harmony with the ancestors.

Enga Family, Marriage, Men and Women

Enga Men and women have traditionally occupied different homes because some Enga myths suggest women may be unclean and dangerous to men, especially during menstruation. Women are therefore forbidden to enter men’s houses, and although men visit their wives to discuss family matters, they do not sleep there. Despite this separation, the nuclear family — husband, wife, and unmarried children — remains the basic unit of domestic production and reproduction. In polygynous households, a man oversees the separate gardens and pig herds managed by each wife, coordinating their work to meet clan obligations. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Mae society has traditionally maintained a clear division of labor by sex. Men perform the heavy initial tasks of clearing, fencing, and tilling gardens and coffee plots, while women and girls handle daily maintenance — planting, weeding, harvesting, and processing crops. Women also care for pigs and children, prepare food, fetch water and firewood, and support men’s political and ceremonial activities through their labor. Men build houses; women provide thatching grass and food for the builders. Women’s work thus sustains the domestic economy and the broader social system.

Until the 1960s, polygyny was a marker of wealth and prestige, with about 15 percent of men having multiple wives; today, monogamy is more common. The levirate — the marriage of a man to his deceased brother’s widow — is the only prescribed form, while marriage within one’s own or one’s mother’s or wife’s subclan is strictly prohibited. Parents, especially fathers, typically arrange first marriages, and postmarital residence is ideally patrivirilocal. Because marriage creates enduring exchange ties between clans, divorce is rare, and adultery, particularly by women, is severely punished. These customs, however, have weakened with the spread of Christianity, education, wage labor, and alcohol use.

Mothers train daughters in household and gardening work until marriage, when the young women move to their husbands’ communities. Boys, at about age six or seven, move into their fathers’ men’s houses, where male kin instruct them in economic, political, and ritual matters. Inheritance passes mainly through the male line: fathers divide land, crops, livestock, and houses among their sons, while daughters receive domestic goods from their mothers at marriage.

In traditional Engan society, young men once underwent an initiation rite known as sangai. During this ceremony, boys were kept in seclusion to undergo purification. As part of the ritual, their eyes were ceremonially washed with water to symbolically cleanse them of any contact with women. During this period of isolation, they were also instructed in the oral traditions, history, and values of their tribe. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Enga Kinship and Land

All Mae Enga are members of segmentary patrilineal descent structures, based on male descent, within which residential and cultivation rights to land are successively divided. The largest patrilineal descent groups have as many as 6,000 members. Each kinship group comprises a cluster of contiguous clans, averaging about eight and ranging from four to twenty. The eponymous founders of these clans are thought to be the sons of the kinship group founder. The mean size of an exogamous, localized patrician group is about 400 members, ranging from 100 to 1,500. A clan contains two to eight subclans named after the clan founder's sons. In turn, the subclan is divided into two to four named patrilineages, which are established by the sons of the subclan founder. Patrilineages consist of twenty or more elementary (monogamous) and composite (polygynous) families, the heads of which are typically considered to be great-grandsons of the lineage founder. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

mysterious Ambum Stone created at least 3,500 years ago in Ambum, Enga Province, From Enga Show

The Mae Enga kinship terminology system resembles the Iroquois bifurcate-merging system in that it distinguishes between generations but not seniority within them. The Mae also recognize four broader categories of kin terminologically: agnates, patrilateral cognates (on the father’s side), matrilateral cognates (on the mother’s side), and affines. Iroquois kinship, also known as bifurcate merging, distinguishes between same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings, as well as gender and generation. The brothers of an individual’s father and the sisters of an individual’s mother are referred to by the same parental kinship terms used for father and mother. The sisters of the individual’s father and the brothers of the individual’s mother, on the other hand, are referred to by non-parental kinship terms commonly translated as "aunt" and "uncle." The children of one's parents' same-sex siblings—i.e., parallel cousins (children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister)—are referred to by sibling kinship terms. The children of aunts or uncles, i.e., cross cousins (two cousins who are children of a brother and sister), are not considered siblings and are referred to by kinship terms commonly translated as "cousin." [Source: Wikipedia]

Enga clans have boundaries defining their homesteads. The Mae Enga this within the 520-square-kilometer Mae district. Traditionally, patricians claimed rights to all the arable land, forests, and marshlands within their territories, and neighboring clans frequently engaged in warfare to defend or extend their territories. Since the 1960s, the combination of a rapidly growing population and the conversion of farmland to coffee and cattle production has intensified conflicts between clans over access to land, economic resources, and political office. The number of people from Mae who have emigrated to other provinces to seek urban or rural employment has not been great enough to improve the situation.

Enga Villages, Houses and Life

part of an Enga village, From Enga Show

The traditional Engan settlement style consists of scattered homesteads dispersed throughout the landscape. Historically, the staple food was sweet potatoes, sometimes supplemented by pork. Modern Enga now eat more store-bought rice, as well as canned fish and meat but sweet potatoes still make up around two-thirds of the Raiapu diet and is their main crop. Pigs remain culturally valuable, and elaborate systems of pig exchange, known as "tee," mark social life in the province. The Raiapu practice extensive agriculture in their highland region. [Source: Wikipedia]

Mae Enga men and women occupy separate houses dispersed among the gardens and groves within each clan parish's territory. Each parish has an average population of 400 clansmen, their in-married wives, and their children, and exploits about 5.2 square kilometers of irregular terrain. One-story dwellings hug the ground and are built with double-planked walls and thickly thatched roofs to keep out the cold and rain. The houses are all much the same size and externally similar, but whereas a woman's house usually shelters one wife, her unwed daughters, her infant sons, several pigs, and family valuables, the average man's house contains about six or seven closely related patrilineal relatives, including boys, and their equipment. Wabag township is a public service and commercial center made up of mostlt of Enga but also containing non-Enga people and Europeans. It has paved streets, Australian-style wooden houses, electricity, and piped water. All-weather roads link Wabag with administrative posts and mission stations within Enga, as well as neighboring provincial centers. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The main forms of entertainment for the Enga have traditionally been clan festivals and rituals in which men lavishly adorn themselves and their daughters with plumes, shells, paints, and unguents, and dance and sing. Musical forms and instruments are basic but poetic and oratorical expression is elaborate. Painting and sculpture were uncommon in the past but a small school of Enga painters has flourished in Wabag since the 1970s. In the past, local medical experts used simple cures for minor ailments, enchanted foods for "magically induced" illnesses, and crude, often fatal, surgery for serious arrow wounds. Nowadays, people usually visit government and mission clinics for treatment. ~

Leadership among the Enga is based on merit rather than inheritance. Men rise to prominence through their prowess in warfare, deep knowledge of rituals, eloquence in speech, and personal charisma. Although leadership is traditionally a male role, the Enga have produced a number of respected female leaders as well. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Enga Economic Activity

making ash salt, From Enga Show

The Enga people have traditionally been sedentary farmers who grow sweet potatoes as their staple crop and raise pigs and chickens. Coffee and pyrethrum are cultivated as cash crops. Pigs, pearls, shells, axes, and plumes are symbols of wealth are exchange of these items have been important parts of social occasions. The large Porgera Gold Mine is located in Enga Province.

The Enga people are renowned for their distinctive method of traditional salt production, a practice that reflects both ingenuity and deep knowledge of the natural environment. Their salt is derived from a particular species of tree found in the region. The process begins by immersing pieces of the tree in a salt lake for several weeks, allowing the mineral-rich water to infuse the wood. Once thoroughly saturated, the wood is dried and then burned to ash. The salt is extracted from the ashes by carefully straining the residue, leaving behind fine, pure salt crystals. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The Mae Enga practice an intensive long-fallow swidden system that relies on family labor, simple tools, and skilled composting and drainage techniques. Their staple crop is the sweet potato, supplemented by taro, bananas, sugarcane, Pandanus nuts, beans, leafy greens, and introduced crops such as potatoes, maize, and peanuts. Since the 1960s, coffee, pyrethrum, potatoes, and more recently, orchids have become key commercial products. Pig husbandry remains central to Mae life, providing daily meat as well as pigs and pork for ceremonial exchanges marking marriages, illnesses, deaths, and compensation for homicides. Small herds of cattle, water buffalo, sheep, and goats exist but play a minor economic role. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Traditionally, the Mae traded ash salt, pigs, and Pandanus nuts with neighboring groups in exchange for items such as tree oil, stone axe blades, palm and forest woods, bird plumes, and marine shells. Within their own society, these valuables — along with pigs and cassowaries — circulated through the Te ceremonial exchange cycle and through gifts marking births, deaths, and marriages. Craft production has remained modest: men build houses and bridges and make tools, weapons, and ornaments, while women weave net bags and make men’s aprons.

Mae involved in Western trades have mostly been government workers, mechanics, carpenters, and builders, many of whom have worked for government agencies based in Wabag, where the province’s main banks and stores are also located. Small trade stores are scattered across clan territories. As of the 1990s, they sold imported goods such as canned food, soap, kerosene, and cigarettes. Wabag and mission settlements host markets where women sell vegetables and homemade goods, and some women use sewing machines to make simple clothing for sale. A handful of bush workshops and dance halls offering beer have also appeared, reflecting the slow shift toward a cash economy.

Engan Tee Ceremony

The Hagen and Goroka Festivals, along with the Engan Tee ceremony, were established to foster peace and reconciliation among rival clans and to ease long-standing hostilities with pigs serving as a means of exchange. While pork is an important part of the Engan diet, the cultural value of pigs extends far beyond their role as food. Among the Enga, a man’s status and prestige are measured by the number of pigs he owns. Pigs function as the primary medium of exchange for bride-price, major transactions, and compensation payments. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Despite strong inter-clan alliances, the Engans—like many Highland groups—have a long tradition of tribal warfare. To reduce this violence, Engan leaders in the 1850s introduced the Tee ceremony, a ritual based on the Engan word tee, meaning “to ask for.” During these ceremonies, men present pigs, money, and other valuables to rival clans as compensation for deaths or to resolve disputes. When a pig is given to atone for a killing, the bereaved clan stages a symbolic attack on the giver before accepting the payment, thus formalizing reconciliation. These exchanges not only demonstrated a man’s wealth and influence but also strengthened relationships and trade networks between clans.

A larger and more elaborate version of the ceremony, known as the Mamaku Tee, involves exchanges between the Engans and neighboring Highland peoples. Participants trade pigs, bilums (woven string bags), and kina shells—highly prized items whose name, Mamaku, literally means “kina shell.” These interregional exchanges once encouraged trade between Highlanders and coastal tribes, where the shells originated. Today, however, such traditional ceremonies are gradually fading from practice.

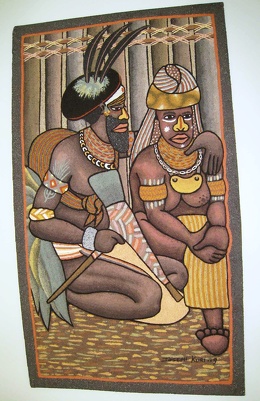

Enga Sand Painting

Enga's sand painting art is an unusual art form in which is ground from the myriad of different coloured stones and earth found in Enga province and used make images that are mainly brown, black and gray in color. According to Enga Tourism: Enga's sand painting evolved out of the workshop at the Take Anda in the late 1970s and early 1980s and has become a contemporary art style that is distinctly Engan. Artworks, typically depict scenes of Enga's traditional life and local wildlife, particularly the birds. Portraits of well known figures are also popular. [Source: Enga Tourism]

One of the best known Enga sand painters is the sculptor Akii Tumu, who graduated from the National Art School in Port Moresby in the early 1980s. Dr. Robin Torrence of the Australia Museum wrote: He developed the time-consuming technique while he was head of the Enga Culture Centre in response to a lack of funds for buying canvas, paints and brushes. To make the sand used in the artworks, the artist grinds up coloured stones from secret source locations and sprinkles single colours of the ‘sand’ onto small glued areas on a board, and then removes the excess sand once the glue has dried. [Source: Dr Robin Torrence, Australia Museum, March 24, 2010]

Steps to make an Engan sand painting: 1) the process begins by selecting colours naturally occurring in the Earth and grinding these to a fine sand. 2) The outline of scenes and subjects are then drawn on to wooden boards before the colouring in process starts. 3) Glue is painted on the boards where sand of the colour chosen will be sprinkled by hand to the board, sticking to the glue, which dries it into place. 4) The true artistic skill comes from the experience of knowing which colours to place where, to truly bring out these natural colours, shades and contrasts.

On works by artists Lucas Kiske and Joseph Kuri at the Australia Museum, Torrence wrote: Unlike earlier versions that were more similar to traditional motifs, the recent forms of sand paintings depict vignettes of traditional Enga daily life in a realistic modern style, making them more readily accessible to Westerners. Lucas's picture shows a hunter shooting at a possum in a tree, his dog ready to pounce should the prey try to escape; Joseph's artwork portrays a courting man and woman seated, wearing full traditional finery of shells, feathers and woven cane. In both pictures the man carries the traditionally important stone axe.

Suli Muli People

One of the most distinctive Engan tribes is the Suli Muli, a relatively small group that lives in scattered communities the rugged mountains of Enga Province.While their precise origins are uncertain, the name Suli Muli is said to derive from the melody of a song composed by a musician from Madang Province. A defining feature of Suli Muli identity is their striking use of black face paint. [Source: Tribes of Papua New Guinea; Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

The Suli Muli apply their distinctive black face paint to their faces as a symbol of their identity and strength. Black paint is worn by both men and women. The paint is made from a mixture of charcoal, ash, and oil, and it is applied to the face in intricate patterns that vary from person to person. The patterns are often symbolic and represent important elements of Suli Muli culture, such as the sun, the moon, and the stars. In addition to their use of black face paint, the Suli Muli people have many other unique cultural traditions. They are skilled farmers and hunters, and have a rich oral tradition, with stories and legends that have been passed down from generation to generation.

In addition to face painting, the Suli Muli coat their bodies with clay, mud, plant oils, and pig fat—each material contributing to their unique ceremonial appearance. Suli Muli men are known for their towering wigs made from their own hair, moss, and plant fibers, reminiscent of the elaborate headdresses worn by the Huli Wigmen of Hela. Their rounded headpieces, adorned with feathers from birds of paradise, eagles, and parrots, are iconic symbols of Engan heritage. Their presence, like their attire, commands attention and respect. Suli Muli women also wear large headdresses crafted from moss and plant fibers. Many women practice facial tattooing, with intricate designs that can sometimes cover the entire face—serving as both adornment and a mark of cultural pride.

In performance, Suli Muli men arrange themselves in spear lines or circles, leaping rhythmically in unison to the beat of the kundu drums as they chant. Two of their most celebrated dances are the Mali and the Shangai. The Mali is a social dance performed by both men and women, while the Shangai is reserved for celebrations following the traditional initiation into manhood.

Porgera Gold Mine

The Porgera Gold Mine is a major open pit and underground gold mine located in Enga Province, approximately 600 kilometers (370 miles) northwest of Port Moresby. It has been a significant contributor to the nation's export earnings but has recently been a focal point of violence and production shutdowns due to issues including tribal conflict, a government takeover process, and a decline in royalties for landowners. [Source: Google AI]

The Porgera mine is situated at an altitude of 2,200 to 2,600 meters (7,220 to 8,530 feet). Open pit and underground mining operations have produced over 20 million ounces of gold since 1990. The mine is powered by the Hides Power Station in the neighboring Hela Province, connected by a 75-kilometer transmission line.

The Porgera mine is owned by the Porgera Joint Venture (PJV), with Barrick (Niugini) Limited (BNL) holding a 95 percent interest and Mineral Resources Enga (MRE) Limited owning the remaining 5 percent. The mine is operated by BNL, though the government has been involved in negotiations and a takeover process in recent years.

At its peak, the mine contributed over 10 percent of Papua New Guinea's total export earnings and employed over 3,300 Papua New Guineans. Violence has been fueled by issues like the cessation of royalty payments during the pandemic, leading to widespread turmoil, displacement, and shortages of essential supplies in Enga Province. The closure of the mine in 2020 led to a significant increase in informal and unregulated mining activities.

Enga Society, Conflicts and Unrest

Enga society is not organised around a single chief or headman, rather it is wealthy men who have political and administrative control. Traditional Mae society was relatively egalitarian and economically homogeneous, and it remained so in the 1980s despite the effects of international commerce. At that time approximately 120 patrician families were significant landholding units and were corporately involved in a wide variety of events.

Enga clans have boundaries defining their homesteads across the territory and have been known to fight with each other over land, marriage exchanges, or vengeance. Clans traditionally engaged in warfare and peacemaking, initiated payments of pigs (today, money) as compensation for slain enemies and allies, organized large-scale distributions of pigs and valuables in the elaborate interclan ceremonial exchange cycle, and participated in irregularly held rituals to propitiate clan ancestors. These activities have not been directed by hereditary or formally elected clan chiefs; rather, they are coordinated by influential and capable men who have acquired "big names" through their past managerial successes. [Source: Mervyn Meggitt,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

A clan's arable land is divided among its subclans, which hold funeral feasts for the deceased and exchange pork and other valuables with matrilateral kin. They also compensate the matrilineal kin of members who have been insulted, injured, or fallen ill. Bachelors usually organize their purificatory rituals on a subclan basis. Subclan land, in turn, is divided among patrilineages, whose members contribute valuables to the bride price or return gifts when their juniors marry into other clans. Lineage members also help each other build houses and clear garden land.

Today, clan solidarity, as well as interclan hostility, significantly influences who individual voters support in national, provincial, and local council elections. These Australian-inspired governmental entities provide extraclan public services, such as schools, clinics, courts, constabularies, post offices, and roads, on which Mae now depends heavily. ~

Within the clan, social control is largely exercised through public opinion, including ridicule and implicit threats by patrilineal relatives to withdraw economic support and labor, both of which all families rely on. There is also the pervasive influence of prominent big men in informal gatherings. The ultimate sanction, even within the household, is physical violence. Formerly, clans within a kinship group or neighborhood could resort to similar, jointly steered courts to reach compromises, especially over land or pigs, but such negotiations frequently erupted in bloodshed.

The Australian colonial administration supplemented these courts with more formal and effective Courts for Native Affairs. After independence, these courts were replaced by Village Courts with elected local magistrates. Nevertheless, despite attempts by armed mobile squads of national police to deter them, clans in conflict, whether over land encroachment or homicides, still quickly resort to warfare to settle matters.

Tribal violence has been a way of life in Enga, although traditional weaponry, rules of engagement, and peace treaties kept casualties low. However, this norm has begun to change in the 21st century. The greater use of firearms and mercenaries, as well as the disregard for rules of engagement, has led to a greater loss of life. Firearms are believed to have been stolen from government armories. During an audit in 2004 and 2005, only a fifth of the 5,000 Australian-made Self Loading Rifles and half of the 2,000 M16s delivered to the Papua New Guinea Defence Force (PNGDF) from the 1970s to the 1990s were found in government armories. [Source: Wikipedia]

Fighting erupted after the 2022 Papua New Guinean general election, displacing thousands from their homes. The fighting continued as different tribes ambushed each other over various disputes, leading to villages being abandoned. Many inhabitants fled to the capital city of Wabag to escape the violence. In February 2024, 69 people were killed in a massacre in Akom, 30 minutes from the capital. This was the worst loss of life since the Bougainville conflict of the 1980s and 1990s.

Paiela and the Papuan Body Counting System

The Paiela (Payala) are an indigenous people from the Porgera-Paiela district of Enga Province in Papua New Guinea, who are known for their distinct cultural practices, such as the intricate body counting ritual. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Ipili, Ipili-Payala numbered about 50,000 in the early 2020s and 98 percent were Christian.

Despite modernization and conflict, cultural traditions are still deeply embedded in their way of life. Their unique marriage couting ritual that involves counting pairs of integers using stakes. Pigs are tied to the stakes and counted before being distributed to the bride's matrilineal and patrilineal relatives. The Paiela and Foe languages and 60 Trans-New Guinea Languages such as Fasu and Oksapmin use a body-part counting system. Counting typically begins by touching (and usually bending) the fingers of one hand, moves up the arm to the shoulders and neck, and in some systems, to other parts of the upper body or the head. A central point serves as the half-way point. Once this is reached, the counter continues, touching and bending the corresponding points on the other side until the fingers are reached.

The Porgera-Paiela district of Enga Province is a remote area in the Papua New Guinea Highlands that is rich in resources. The major Porgera Gold Mine located there. The district has faced significant rural decay due to neglect, tribal fighting, and the closure of its airstrip in 1996. Sociopolitical contextThe district has a history of conflict between tribes, which has led to loss of life and destruction of property.

According to “Growing Up Sexually: Adolescents by definition neither copulate nor sexually reproduce. They are considered chaste and sterile, in fact not really male or female, until they are married and become parents. The boy’s puberty rite include periodical seclusion with an imaginary “ginger woman” to have her grow him into marriage, using “her”, it seems, as a rehearsal wife; sexual intercourse is tabooed during the ritual period. Genitals are considered so obscene, that one does not look at or touch one self’s; sexual intercourse is equated with seeing the genitalia. [Source:“Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, September 2004]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025