Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

MAFULU

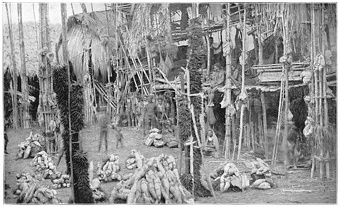

Scene at Big Feast at Village of Seluku (Showing head feather erections and back feather ornaments) from the book: “The Mafulu Mountain People of British New Guinea” (1906)

The Mafulu people and other Fuyuge-speaking people live in the Goilala District of Central Province in the mountainous Owen Stanley range. They are known as Fuyuge, Fuyughe, Goilala and Mambule. Traditionally, their villages were built on ridge crests and surrounded by stockades for defense. They have a rich cultural and spiritual tradition, with a creator force named tidibe being central to their myths and worldview. Since World War II, some Mafulu who have moved to Port Moresby are often grouped with the neighboring Tauade people under the name Goilala.

The Goilala District is only around 50 kilometers away from Port Moresby, the capitol of Papua New Guinea, as the crow flies but is difficult to reach by roads, which are poorly maintained and through very mountainous terrain. It takes about 45 minutes by air to reach it in a small plane.

Language: The Fuyuge language is part of the Trans-New Guinea language group and is spoken by approximately 14,000 people across about 300 villages in river valleys like the Auga, Vanapa, and Dilava. There are several dialects, including Central Udab, Northeast Fuyug, North-South Udab, and West Fuyug. Fuyuge is quite divergent from the other two members of the Goilalan language family, sharing only 27 percent of its vocabulary with Tauade and 28 percent with Kunimaipa. The dialects of Fuyuge differ considerably from valley to valley.

History: One anthropologist wrote in 1906: The Mafulu people are of short stature, though perhaps a trifle taller than the Kuni. They are as a rule fairly strong and muscular in build.” Before European contact, the Mafulu maintained trade and exchange relations with the neighboring Tauade and Kunimaipa and with the more distant Mekeo. Early contact between the Mafulu, the Sacred Heart Mission, and the government in the late 1880s was characterized by open conflict. In 1905, the Sacred Heart Mission was established in Popole. Most ethnographic data on the Mafulu is based on R. W. Williamson's research from 1910. Mafulu communities were not directly affected by combat during World War II. After the war, many young men left the area to work as laborers on coastal and Kokoda plantations. More recently, others have moved to the Port Moresby area for employment. The region itself has remained relatively isolated due to its mountainous terrain, which has hindered road development. The region is serviced by a small local airstrip. [Source: William H. McKellin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Book: “The Mafulu Mountain People of British New Guinea” by R.W. Williamson (1906) available on Project Gutenberg

RELATED ARTICLES:

HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS HIGHLAND TRIBES OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: KALAM, ASARO MUDMEN AND HULI WIGMEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MARING, TAMBUL, SUMAU ioa. factsanddetails.com

MELPA: MT. HAGEN, LIFE, CULTURE AND FAMILY ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHIMBU (SIMBU): HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY AND SKELETON MEN ioa. factsanddetails.com

ENGA PEOPLE: RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MADANG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA: USINO, TANGU, AIOME ioa. factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MENDI, FOI, KEWA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS OF THE GREAT PAPUAN PLATEAU AND WESTERN HIGHLANDS ioa. factsanddetails.com

EASTERN HIGHLANDS GROUPS OF OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: GAHUKU, TAIRORA, AWA, GIMI ioa. factsanddetails.com

SIMBARI: HISTORY, LIFE, SEX, INITIATIONS ioa. factsanddetails.com

FORE PEOPLE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: HISTORY, LIFE, RELIGION, CULTURE, KURU ioa. factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN MOROBE PROVINCE: WANTOAT, SELEPET AND SIO ioa. factsanddetails.com

Mafulu Religion and Rituals

According to Mafulu legend, Tsidibe, a hero in Mafulu mythology, crossed the mountains from the north and brought the first humans, crops, animals, and social activities to the region. Tsidibe's journey is marked by stones and oddly shaped rocks. The current Amidi is the embodiment of the Omate, without which the women, animals, and crops of the clan could not reproduce. The Mafulu fear the spirits of the dead, particularly those of the amidi, who are often blamed for illness and accidents. After 1905, the Sacred Heart Missionaries Christianized most of the Mafulu and established a training center for local catechists in Popolé. [Source: William H. McKellin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Magicians or sorcerers had the power to cause and cure illness and death. They could also divine the progress of an illness. However, the power to cause illness was only to be exercised as retribution against people from other villages. Following the introduction of Christianity and the establishment of a religious training school, the region produced Roman Catholic catechists. ~

People are believed to have a ghostly spirit that inhabits the body during life and leaves at death. These spirits can become malevolent and are blamed for illness and misfortune. Once the mourning rituals are complete, the ghosts retreat to the mountains, where they can take the form of various plants and animals. ~

The main ceremony is the Gabé, a large, intertribal feast that draws guests from many distant communities. Gabés are spaced about ten to twelve years apart, which gives the hosts time to grow the large gardens and raise the litters of pigs needed for the feast. In addition to its social aspect, the gabé involves the washing and final disposal of the bones of a deceased amidi. During the feast, the bones that had been hung in the emone are brought out, splashed with blood from the pigs killed for the feast, and redistributed to the deceased's close relatives. Rites of passage for boys and girls may be performed alongside the gabé, though separate pigs are required for each ceremony.

Traditionally, there were specific ceremonies for the birth of the chief's first child. Other ceremonies performed for all children included admitting both boys and girls to the emone, though only boys could sleep there. The assumption of a perineal band, preceded by lengthy seclusion, occurred prior to adolescence. Other ceremonies were held when boys' and girls' noses and ears were pierced, when boys were given drums and songs, and when people were married. Death and mourning ceremonies for chiefs differed from those for others. ~

Mafulu Family, Marriage and Kinship

A Mafulu household consists of a husband, his wife(s), and their children. Other members of the extended family may also live with them. The wives and their young female and male children sleep together in one house, while the husband and his adolescent sons usually sleep in the village men's house. [Source: William H. McKellin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Polygamous marriages are common, particularly among prestigious men. Clans and villages are exogamous. There does not appear to be any pattern of intermarriage among communities. Typically, a marriage proposal is made by a boy through one of the girl's close female relatives. However, marriages by elopement and childhood betrothal are also practiced. A gift of a pig and other bridewealth legitimizes a marriage. Postmarital residence is patrilocal, meaning the couple lives in the husband’s family home or community. Divorce is not uncommon. A wife typically initiates divorce by leaving her husband's home and moving in with her parents or siblings, or with a new husband. Although there may be claims for the return of bridewealth following divorce, they are usually ineffective. ~

Children participate in many day-to-day activities with adults, such as gardening and hunting. Games often involve taking on adult roles. Children attend primary schools administered and staffed by the district department of education. Inheritance is patrilineal, based on descent through the male line. Personal, movable property is divided among sons or other male relatives when an owner dies. Women only inherit personal property and have no claim to land. ~

The kinship ideology is patrilineal, meaning it is based on descent through the male line. In practice, however, an individual can move to a village with collateral relatives, join the clan there, and still be affiliated with the clan of their previous residence. Clan membership is based on common descent and residence. Clans are unnamed, non-totemic groups identified by the names of their chiefs. The chief embodies the "prototype" (omate) given by a mythological ancestor. [Source: William H. McKellin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Members of a clan hold rights to land, which resident clan members exercise. A particular clan owns village land, though individuals have private usufructuary rights to the land and ownership of the houses they build there for as long as the houses stand. The neighboring bush is also owned jointly by the clan. Individual gardeners control access to cleared land until it returns to uncultivated bushland. At that point, jurisdiction reverts to the clan. Hunting land is also the property of the clan, with access controlled by clan members, though not restricted to them. No individual has the right to dispose of clan land.

Mafulu Life

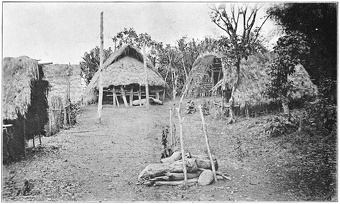

Communities are composed of two to eight villages. Villages are usually associated with specific clans and have closer ties to other villages within the community that belong to the same clan. The number of houses in each village varies considerably, ranging from six to eight to thirty. Traditionally, villages were situated along the crests of ridges and surrounded by stockades for defense. Houses were built in two parallel rows with an open mall between them. The emone, or "men's house," was located between the two rows of houses at one end. Special dancing villages were built for large feasts held about every ten to twelve years, bringing together people from other villages in the community. [Source: William H. McKellin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The plastic arts consist primarily of painting tapa, dancing aprons, burning or cutting abstract designs on smoking pipes, and constructing feather headdresses for dances. Musical instruments include kundu-style drums, which accompany dancing at feasts; Jew's harps; and flutes. Some unidentified traditional herbal medicines were ingested for stomach ailments and applied topically to wounds. ~

Women are responsible for planting sweet potatoes and taro, clearing gardens of weeds, collecting food from gardens, cooking it, and gathering firewood. They also care for the pigs. Men primarily plant yams, bananas, and sugarcane; cut down large trees; build structures; and hunt. They also help women with their work. ~

Mafulu Agriculture, Food, Hunting and Economic Activity

The Mafulu are swidden (slash and burn) horticulturalists whose main crops are sweet potatoes, taro, yams, and bananas. They also cultivate sugarcane, beans, pumpkins, cucumbers, and pandanus. They raise pigs and hunt wild pigs, cassowaries, wallabies, and bandicoots with the help of their dogs. The household is the basic unit of production and consumption. Most food is roasted or steamed in bamboo sections, while pig and other meats are cooked in earth ovens. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The Mafulu produce bark cloth (tapa), which is used for capes, vests for widows, dancing aprons, and loincloths. Netting is used for string bags, hunting nets, and hammocks. Smoking pipes are made from bamboo. Stone adzes, which were used in the past to cut down trees and clear gardens, have been replaced by steel bush knives and axes. Spears, stone clubs, bows, and bamboo-tipped arrows are used for warfare and hunting. The Mafulu also make various musical instruments. ~

Their trade consists primarily of pigs, feathers, dog teeth necklaces, and stone tools. They trade stone tools and pigs with the Tauade and others in neighboring valleys who lack the appropriate stone or skills. In exchange, they receive feathers, dogs'-teeth necklaces, and other valuables. They also trade with coastal peoples for clay pots and magic. ~

Mafulu Social and Political Organizations

The largest effective social group is the community, which is composed of several villages. The villages within a community (particularly those of the same clan) cooperate in feasting, ceremonies, protection, and, occasionally, hunting and fishing. The number of villages within a community belonging to the same clan varies as they divide and recombine over the course of several years. Villages within a community of the same clan have a common chief (amidi), who usually inherits his position through primogeniture. The chief's ceremonial emone, or men's house, located in his village, is the site of feasts. Clans are not named, nor do they share a common totemic emblem. Instead, people identify their social affiliation by using the name of their amidi. [Source: William H. McKellin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

The community is the largest political unit. Each clan within the community has a chief who has a house in each of his clan's villages. However, his primary residence is in the same village as his ceremonial men's house. The amidi's only authority is as the hereditary leader of his clan within the community. There are also clan leaders responsible for warfare, the division of pigs, and other political activities. Decision-making within communities is done cooperatively by the amidi of the clans and other leaders in the community. ~

collapsed chief’s burial platform; beneath which his skull and some of his bones are interred underground (1906)

The Amidi exerts control only within a village, as the senior member of a clan. In most cases of homicide, seduction, and so on, members of the aggrieved clan or village take retribution on the offenders themselves if they are from outside the community. Gossip and threats of shame and retribution, including self-mutilation or suicide, also control open disagreement and violence within the community. ~

Even after European contact, raids between communities continued. The most frequent causes of disputes were the seduction of wives and the theft of pigs. The warfare and sorcery that often followed were waged between communities. Retribution could be taken out on any member of the opposing clan or community. Although early missionary sources state that cannibalism was not practiced, this report is disputed by later missionary accounts and ethnographic studies.

Tauade

The Tauade live approximately 50 kilometers away as the crow flies from Port Moresby, the capitol of Papua New Guinea, in the mountains in Central Province in the Goilala District towards the northeast. Most of them live in 52 or so villages on ridges among deep river valleys and high-forested mountains. In 1966, the population of the Tauade Census districts was 8,661. The precontact population was probably smaller. A number of Tauade have migrated to Port Moresby in recent years. [Source: C. R. Halipike,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~; Joshua Project]

The Tauade are also known as Goilala and Tauata. They live mainly in the valley of the Aibala River, at 8° S, 147° E at elevations from 600 to 3,000 meters (1,970 to 9,842 feet). The lower slopes are grassland, produced by prolonged burning, and the upper slopes are forested. Rainfall averages 254 centimeters (100 inches) per year, humidity is seldom below 75 percent, and the yearly average temperature at 2,100 meters (6,890 feet) is 18°C (64̊F) . The main rainy season lasts from the beginning of December until the end of May, and the months of June to September tend to be the driest. ~

Language: The Tauade language is a member of the Goilalan Family of Papuan languages. It is one of a number of closely related language and dialects. The name "Tauatade" has been used by the neighboring Fuyuge tribes to designate the speakers of all these dialects, passed — slightly modified — into official usage as "Tauade." ~

History: The first recorded European visitor to the Goilala area was Father V.M. Egidi of the Sacred Heart Mission, around 1906. The first Australian government patrol showed up in 1911. The pacification of the area was a slow process that was not fully accomplished until after World War II. The Sacred Heart Mission established a school in Kerau in 1939. In 1962, the government established a school at Tapini, the subprovince headquarters. Graded tracks constructed under the mission's supervision extend throughout the subprovince. However, there is no vehicular road link with the coast. An airstrip was built in Tapini in 1938, and another was built in Kerau in 1967. These airstrips provide the main access to Port Moresby,Considerable labor migration and an influx of trade goods, notably steel axes and other tools, as well as alternative sources of food, such as rice, have occurred. Government incentives to raise cattle as a source of income have generally been unsuccessful. Local councils were established in 1963, and elections for the national House of Assembly were held the following year. Papua New Guinea gained independence in 1975.

Tauade Religion and Views of Life and Death

For the Tauade, the relationship between the “wild” (kariari) and the “tame” or domesticated (vala) is central to their worldview. The forest represents the antisocial opposite of village life, yet it is also the source of vitality and creativity. The Tauade have no concept of gods, but their mythology centers on the agotevaun—culture heroes who shaped the land, tormented humans, and taught them ceremonies, customs, and crafts. Women are portrayed as the creators and sustainers of culture through their association with fire, cooking, and craft, while men are often depicted as destructive. [Source: C. R. Halipike,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Each plant and animal species is believed to be sustained by a supernatural prototype, often embodied in a rock; if the prototype were destroyed, the species would vanish. Big-men are thought to share in this life-sustaining power. When a big-man died, his body was placed in a sacred enclosure where boys were also secluded during initiation. The boys were fed special foods, danced, and endured nettle beatings to instill toughness.

The Tauade recognize many malevolent spirits inhabiting streams, rocks, and trees. Some individuals use magical substances and spells, but magic and sorcery play a minor role in daily life. Tauade ceremonies revolve around pig killings, the distribution of pork and garden produce, speeches, and dancing. The largest events are held to honor the dead and are organized by big-men, who invite neighboring—sometimes rival—tribes. These occasions are highly competitive, as hosts seek to outdo guests through displays of generosity, oratory, and endurance in all-night dances. The events culminate in the slaughter of many pigs, with grand dance villages built specially for the occasion.

A person is composed of flesh, energy or strength, and a soul. After death, the soul becomes a ghost; the flesh decays, and the energy dissipates. The ghost world mirrors the living one in reverse—its food stinks, and its inhabitants sleep by day and wake by night. All souls, regardless of social status, share the same afterlife. The cult of the dead was central to Tauade ritual life. Big-men’s bodies were left in raised baskets to decompose, while ordinary people were buried. After decomposition, bones were gathered for a great feast and dance honoring the ghosts. The bones of big-men were placed in trees, and those of others in clan caves.

Tauade Family, Marriage, Men, Women and Kinship

The nuclear family is the main unit of production and cooperation. Traditionally, men have been are responsible for felling trees, clearing land for gardens, building fences, climbing pandanus trees to harvest nuts, and constructing houses. They also have planted taro, yams, sugarcane, bananas, and tobacco. Women have traditionally planted sweet potatoes and done most of the work in the gardens. They have also carried harvested pandanus nuts home in string bags and collected dried pandanus leaves to bring to hamlets where new houses have been built. Women also have cared for the pigs. ~ Parents are affectionate and indulgent toward their children. Traditionally, boys at puberty underwent seclusion and ritual beatings to instill toughness. Some children now attend mission or government schools. [Source: C. R. Halipike,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

In the 1970s and 80s, about 10 percent of men were polygynous and relations between co-wives were often tense, with most divorces following the taking of second wives. Marriages are usually arranged by a woman’s father or brother, with sister exchange being the ideal though uncommon form. Infant betrothal was once common, with bride-wealth paid at marriage—a custom that continues. Adultery is frequent and may lead to compensation or violence. Residence is typically patrilocal, though men often live with their wife’s kin for a time to establish goodwill. Only about 20 percent of marriages occur within the same tribe, and intermarriage is limited by hostility between groups.

Tauade social organization is based on patrilineal clans, each tracing descent from founding ancestors and claiming specific lands and ancestral caves. While descent follows the male line, membership can be flexible, allowing people to claim affiliation with multiple clans. Marriage and homicide within the same clan are rare. Kinship terminology follows the Iroquois system, distinguishing same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings and differentiating between parallel and cross cousins. Clan land is traced to the ancestors who first cleared it, but rights of use have spread widely to cognates, affines, and friends, creating flexible access. Customary land rights must be exercised to remain valid, yet with abundant land, gardens are made freely by groups of friends. Land is not individually owned or inherited; instead, use rights can pass through both men and women. Pandanus trees, however, are individually owned, with plots clearly marked and inherited like property.

Tauade Life, Agriculture and Economic Activity

The Tauade are swidden agriculturists whose principal staple crop is the sweet potato, of which at least twenty-two varieties are cultivated. Other crops include bananas, sugarcane, yams, and taro. Pandanus nuts constitute an important dietary supplement, valued for their ability to be preserved by smoking. Pigs are maintained in a semi-domesticated state, roaming freely in the forest and bush during the day and returning to their owners’ houses at night to be fed sweet potatoes. Gardens are established following the cessation of the rains, and substantial fencing is constructed to prevent pig incursions. The ground is cleared by burning and, in recent times, with the use of steel axes; formerly, stone adzes and wooden digging sticks were employed. Secondary forest is preferred for cultivation, and grassland is seldom utilized. Land is abundant, with a population density of approximately 7.7 persons per square kilometer. The pandanus tree provides the principal source of construction material: its bark is stripped for planks, its dried leaves are used for roofing, and its aerial roots serve as bindings for house frames. Hunting and food gathering, including the pursuit of small animals, cassowaries, and pigs, were probably of greater importance in the past. [Source: C. R. Halipike,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Settlement patterns are characterized by scattered hamlets averaging forty-five inhabitants and about fifteen houses (fewer today), typically situated on ridge crests near the forest margin. Houses are arranged in two parallel rows occupied by women and children, while men’s houses at the head of the rows traditionally accommodated married men and bachelors. In recent times, men’s houses have largely fallen into disuse. In precolonial periods, hamlets were enclosed by stockades, and the open spaces between houses served as venues for feasts and dances. Houses are often sheltered by windbreaks of Cordyline terminalis. Hamlets are occupied for limited periods before being abandoned, though sites are frequently reoccupied after intervals of time. Large ceremonial villages, occasionally containing seventy or more houses, are constructed for major rituals and inhabited only temporarily.

The Tauade do not recognize private ownership of land. Houses are impermanent, and a man’s pigs are slaughtered at his funeral feast. The pandanus tree represents the most significant form of inheritable property. Inheritance is normally patrilineal, though men may acquire usage rights through their mothers. In the absence of male heirs, a man’s daughter may inherit his trees.

In the field of material culture, traditional tools and implements were originally manufactured from stone, used for adzes and bark-cloth beaters. These were later replaced by steel tools, and bark cloth was supplanted by imported textiles. String bags continue to be produced from local plant fibers. The Tauade made no pottery; green bamboo tubes served as cooking vessels. Bows were fashioned from black palm, and bamboo was used for tobacco pipes and as percussion instruments, produced by striking one end of the tube on the ground. Traditional material culture was comparatively simple. The Tauade maintained limited contact with the peoples of Papua’s southern coast but traded feathers for shells—and later for steel tools—along routes passing through Fuyuge territory to the upper reaches of the Waria River. Steel tools were already in use in the Aibala Valley by the time of Egidi’s 1906 visit.

The most prominent form of visual art is the use of feather ornaments in dances. Singing is an integral component of these performances. The Tauade possess an extensive repertoire of string figures, which serve as a common pastime. Plants are traditionally employed for abortifacients, for the treatment of illness, and in magical remedies, reflecting the intersection of practical and ritual knowledge in Tauade society.

Tauade Conflicts and Social and Political Organization

The Tauade are divided into several autonomous named groups occupying ridges between major streams. These groups, often termed tribes, average about 200 members and are subdivided into named clans, each dispersed among five or six hamlets. Hamlets typically consist of groups of brothers and their immediate families, linked by kinship, marriage, or friendship. Men frequently move between hamlets and even between tribes, yet cooperation within hamlets remains strong, and internal conflict is rare. Relations between hamlets, however, are often marked by hostility. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Each hamlet includes at least one big-man (local leader) supported by relatives and allies. Big-men coordinate ceremonies, deliver speeches, and give generously in exchange events. Each tribe traditionally had a senior clan whose leading big-man conducted peace negotiations after warfare. Although big-man status is not hereditary, it often passes within families, and leadership is closely associated with personal ability and lineage prestige. Ceremonial pork exchanges form a central part of Tauade social life, though big-men are not as politically dominant as those in some other highland societies. At the lowest social level are “rubbish men”—usually unmarried, poor, and socially marginal—who were sometimes killed without retribution, unlike big-men whose deaths provoked major vengeance.

Big-men hold no judicial authority, and disputes are common, reflecting the Tauade’s high sensitivity to insult. Conflicts arise over pigs, women, theft, and other offenses. Family disputes are often mediated by kin, and residence in the same hamlet encourages reconciliation. Hamlet members support each other against outsiders but may also pressure a wrongdoer to pay compensation. Adultery cases often end in compensation payments, but no legal enforcement exists outside of government courts. Avoidance and separation are typical ways to manage long-standing hostilities, and the Tauade explain their dispersed settlement pattern as “because of our ancestors.” In cases of homicide, offenders usually seek refuge with their wife’s or mother’s tribe until compensation is arranged.

Traditional Tauade society exhibited high levels of violence, with an estimated murder rate of 1 in 200 per year. Conflict occurred both within and between tribes, most frequently among neighboring groups. Killers were entitled to wear shell emblems symbolizing homicide, admired by women, and revenge could be taken against any member of an enemy tribe. Feuds were often long-lasting, and the death of a big-man could spark full-scale warfare, leading to the destruction of hamlets and gardens. Defeated groups commonly fled to related tribes but usually returned home after a time. Land conquest was unknown, though enemy corpses were occasionally mutilated or eaten to distress their kin.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons and Tauade by C.R. Hallpike.

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025