Home | Category: Kangaroos, Wallabies and Their Relatives

ROCK-WALLABIES

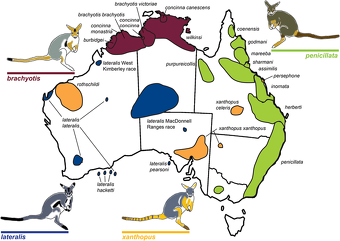

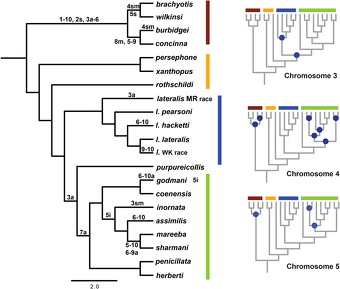

Rock-wallaby (Petrogale) taxa distributions: Taxa are colored in accordance with their chromosomal groupings: the brachyotis group (red); the xanthopus group (yellow); the lateralis group (blue); and the penicillata group (green), from Researchgate

The 19 known species of rock-wallabies belong to the genus Petrogale. They tend to live among rocks, usually near water, and are relatively small, about one meter (three feet) long and weigh around nine kilograms (20 pounds). They move around cliffs and ledges with the agility of mountain goats and occupy similar niches — living in rugged environments with little food but where no predators can touch them. When threatened they can escape by hopping 15 to 20 feet "from one precarious perch to another". They are adapted for rugged terrain with modified feet that can grip rocks with skin friction rather than dig into soil with large claws. The relationship between several of the 19 species is not well understood.

Rock-wallabies tend to have a a high degree of speciation. This due at least in part to their occurrence to complex habitats which are isolated from one another, Petrogale is the most diverse macropod genus. Often colourful and extremely agile, they relatively small to medium-sized marsupials, weighing from one to 12 kilograms. They often live where rocky, rugged and steep terrain can provide daytime refuge. Males are slightly larger than females, with a body length of up to 60 centimeters (two feet) and a tail up to 70 centimeters (2.3 feet). [Source: Wikipedia]

Rock-wallabies are mainly nocturnal and spend their days holed up in steep, rocky terrain that has some kind of shelter (a cave, an overhang or vegetation) and move around in surrounding terrain at night to feed. The greatest activity occurs three hours before sunrise and after sunset. This lifestyle has encouraged rock-wallabies to live small groups or colonies, with individuals having overlapping home ranges of about 15 hectares each. Within their colonies, they seem to be highly territorial with a male's territory overlapping one or a number of female territories. Even at night, the rock-wallabies do not move further than two kilometres from their home refuges.

Generally, there are three categories of habitat that the different species of rock-wallaby seem to prefer: 1) Loose piles of large boulders containing a maze of passageways; 2) Cliffs with many mid-level ledges and caves’and 3) Isolated rock stacks, usually sheer sided and often girdled with fallen boulders. Suitable habitats are limited and fragmented and this has has led to varying degrees of isolation of colonies and a genetic differentiation specific to these colonies even within species..

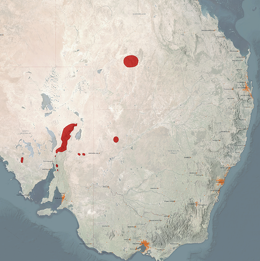

Two species of rock-wallaby are endangered — the brush-tailed Rock-wallaby and black-footed Rock-wallaby . The total populations and range of rock-wallabies has been drastically reduced since the arrival of Europeans, with populations becoming extinct in the south. Declines have also occurred in recent decades with the main culprits being red foxes and competing herbivores, especially goats, sheep and rabbits, diseases such as toxoplasmosis and hydatidosis, habitat fragmentation and destruction, and a lower genetic health due to the increasing isolation of colonies. The extinction of entire colonies is of particular concern. In 1988 at Jenolan Caves in New South Wales, for example, a caged population of 80 rock-wallabies was released to boost what was thought to be an abundant local wild population. By 1992, the total population was down to about seven. The survivors were caught and enclosed in a fox and cat-proof enclosure, and the numbers in this captive population have since begun to increase. Habitat conservation and pest management addressing red foxes and goats appear to be the most urgent recovery actions to save the various species.

RELATED ARTICLES:

WALLABIES: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS AND WALLABIES (MACROPODS): CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, POPULATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WALLABY SPECIES OF SOUTHWEST AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

FOREST WALLABIES (DORCOPSIS): SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRUSH-TAILED ROCK-WALLABIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

HARE-WALLABIES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOKKAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, ROTTNEST ioa.factsanddetails.com

PADEMELONS: SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROO BEHAVIOR: FEEDING, REPRODUCTION, JOEYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

KANGAROOS HOPPING: MOVEMENTS, METABOLISM AND ANATOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALASIA (AUSTRALIA, NEW GUINEA, NEARBY ISLANDS) ioa.factsanddetails.com

Rock-Wallaby Species

Reconstruction of chromosomal rearrangements based on parsimony analysis for Petrogale using only known chromosomal karyotypes; Reconstructions of ancestral karyotypes are highlighted on the main phylogeny and those that could not be resolved for nodes in the phylogeny are indicated in blue for chromosomes 3, 4, and 5; Chromosomal groups are again outlined in color: brachyotis (red), xanthopus (yellow), lateralis (blue); and penicillata (green); Chromosomal rearrangements include: centric shifts, a (acrocentric), m (metacentric), sm (submetacentric); inversions (i); and fusions between two chromosomes (-)

The 19 species of rock-wallaby in the Genus Petrogale are:

Petrogale brachyotis species group

Short-eared rock-wallaby (Petrogale brachyotis)

Monjon (Petrogale burbidgei)

Nabarlek (Petrogale concinna)

Eastern short-eared rock-wallaby (Petrogale wilkinsi)

Petrogale xanthopus species group

Proserpine rock-wallaby (Petrogale persephone)

Rothschild's rock-wallaby (Petrogale rothschildi)

Yellow-footed rock-wallaby (Petrogale xanthopus)

Petrogale lateralis and penicillata species group

Allied rock-wallaby (Petrogale assimilis)

Cape York rock-wallaby (Petrogale coenensis)

Godman's rock-wallaby (Petrogale godmani)

Herbert's rock-wallaby (Petrogale herberti)

Unadorned rock-wallaby (Petrogale inornata)

Black-flanked rock-wallaby (Petrogale lateralis)

Mareeba rock-wallaby (Petrogale mareeba)

Brush-tailed rock-wallaby (Petrogale penicillata)

Purple-necked rock-wallaby (Petrogale purpureicollis)

Mount Claro rock-wallaby (Petrogale sharmani)

Species identification can be difficult. Many look very similar. Hybridization is common within the genus Petrogale, making species identification even more difficult. Fertility is slightly diminished in hybrids, but both male and female hybrids are fertile. The species groups listed above have been confirmed by genetic analysis and their relationships have been well studied, especially in the brachyotis group. However, these studies also revealed that mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences resulted in different phylogenies, a phenomenon called cytonuclear discordance. [Source: Wikipedia]

Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallabies

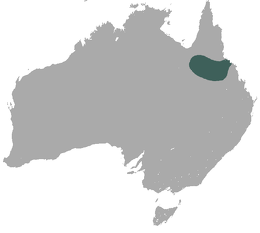

Brush-tailed rock-wallabies (Petrogale penicillata) are also called small-eared rock-wallabies. They inhabit rock piles and cliff lines along the Great Dividing Range from about 100 kilometers north-west of Brisbane to northern Victoria, in vegetation ranging from rainforest to dry sclerophyll forests. Populations have declined seriously in the south and west of its range, but they remains locally common in northern New South Wales and southern Queensland. However, due to a large bushfire event in South-East Australia around 70 percent of all the wallaby's habitat had been lost as of January 2020. In 2018, the southern brush-tailed rock wallaby was declared the official mammal emblem of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), although it has not been seen in the wild in the ACT since 1959. [Source: Wikipedia]

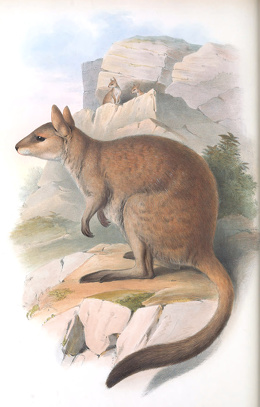

Brush-tailed Rock-wallabies are medium-sized rock-wallabies, with shaggy, thick fur that varies from rufous to grey-brown. They have a characteristic bushy tail, often dark or brown at the tip and longer than the head and body combined. A narrow hybrid zone has formed between Brush-tailed rock-wallabies and Herbert’s rock-wallabies (Petrogale herberti) in the north of Brush-tailed rock-wallabies's range. Some female hybrids are fertile, which allows limited gene exchange between the two populations. Captive brush-tailed rock-wallabies have lived over 11 years. [Source: Kathleen Bachynski, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Brush-tailed rock-wallabies live on rock faces close to grassy areas and often in open forests. They prefer sites with numerous ledges, caves, and crevices and typically occupy sites with a northerly orientation, in order to sun themselves in the morning and the evening. They have traditionally been found a wide variety of suitable rocky areas in habitats, including rainforest gullies, wet and dry sclerophyll forest, open woodland, and rocky outcrops in semi-arid country. But this less so than before. Brush-tailed rock-wallabies was introduced to Hawaii and New Zealand. In Hawaii, a small population descended from two animals, has existed on the island of Oahu since 1916. In New Zealand, brush-tailed rock-wallabies were introduced in the 1870s and can be found on Kawau, Rangitoto, and Montutapu islands. On some of these islands rock-wallabies are regularly culled when their numbers reach pest proportions.

See Separate Article: BRUSH-TAILED ROCK-WALLABIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Allied Rock-Wallabies

Allied rock-wallabies (Petrogale assimilis) are also known as weasel rock-wallabies. They are found in rock-dominated terrain near forests in northeastern Queensland and belong to the P. lateralis/penicillata species complex along with Cape York rock-wallabies, unadorned rock-wallabies, Herbert's rock-wallabies, Godman's rock-wallabies, Mareeba rock-wallabies and the Mount Claro rock-wallabies. It is hard to tell these rock-wallabies apart other than by where they live — with each occupying a specific part of Queensland or northern New South Wales, with on a minimal amount of overlap in their ranges. They all have upper parts that range from brown to grey, and paler underparts. They usually have a dark muzzle and a dark patch around the armpits. On their face is a pale cheek stripe, and across the hips is another pale stripe. slightly. There is some hybridisation. [Source: Wikipedia]

Allied rock-wallabies range in weight from 4.3 to 4.7 kilograms (9.5to 10.35 pounds) and have a head and body length ranging from 51.2 to 49.6 centimeters (20.2 to 19.53 inches). They have large hindfeet, reduced forepaws, and large hindlegs compared to their arms. They stand upright and move bipedally. The coloration may depend on surrounding rock color. They are usually gray-brown on the body with lighter brown underneath and on their appendages, and darker paws and feet. The tail has a brush that becomes darker in coloration towards the end Allied rock-wallabies may live over seven years in the wild. [Source: Sean Maher, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|] |=|

Allied rock-wallabies primarily herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) and are nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They forage at night. Breeding pairs may eat together, and feeding individuals seem to prefer to be near to others. Their home ranges are elliptical in shape and occupy nine to 11 hectares, with extension during the dry seasons, presumably to find more food. Size of the home ranges is not sexually dependent. Allied rock-wallabies have a shelter site, usually a rock overhang, where they stay during the daytime. They are excellent climbers |=|

Allied rock-wallabies are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and engage in year-round breeding though certain times seem to be more common. They are usually found in long-term, monogamous pairs, although females may have extra-pair copulations. The average gestation period is 31 days and the usually number of offspring is one. As with other marsupials, birth occurs early in the developmental process. At birth, young crawl to a pouch. They stay in the pouch on the teat for roughly six to eight months. Sexual maturity occurs at 23 months for males and 17.5 months for females. |=|

Allied rock-wallabies are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Their population numbers are fairly stable, rarely reaching low levels. Their main known predators are feral cats and red foxes but generally are not threatened by predators very much. Drought can impact their food and water supplies.

Proserpine Rock-Wallabies

Proserpine rock-wallabies (Petrogale persephone) are found in fragmented habitats in a small area in Whitsunday Shire along north-east to central coastal Queensland at Conway National Park, Dryander National Park, Gloucester Island National Park, and around the town of Airlie Beach. Discovered in 1976, not officially described until 1982 and declared endangered not long after that, Proserpine rock-wallabies live in elevated rocky outcrops within semi-deciduous microphyll-notophyll vine forests in areas with diverse rock types. They often prefer foothills near open woodlands that contain boulders larger than 0.6 meters in diameter, which are used for shelter. During the dry season, they moves closer to the forest edge to graze. [Source: Morgan Lantz, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Proserpine rock-wallaby

Of the eleven species of rock-wallabies found in Australia, Proserpine rock-wallabies are the third largest. They range in weight from 3.6 to 9.6 kilograms (7.9 to 21.2 pounds) and have a head and body length of 52 to 64 centimeters (20.5 to 25.2 inches). Their lifespan in the wild is up to 10 years. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are slightly larger than females. Males weigh 4.3 to 9.6 kilograms and females weighing 3.6 to 7.4 kilograms.

Proserpine rock-wallabies are dark grey in color and occasionally have a mauve tinge. Their underside is a light cream color. All four paws are black. The tail is dark dorsally with a tuft on end. A white tip on the tail is common and often used in identification; however, not every member of this species displays this trait The back paws have fleshy pads and short, stout, hooked nails for climbing rocks.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Proserpine rock-wallabies are listed as Endangered. Threats to Proserpine rock-wallabies include residential development and tourism in prime habitats, predation by feral and domestic cats and dogs, parasites and diseases transmitted by them. Proserpine rock-wallabies are frequently hit by cars. The five main populations of Proserpine rock-wallabies are separated by unsuitable habitat, preventing gene flow. Natural predators of Proserpine rock-wallabies include dingoes, carpet pythons, goannas, wedge-tailed eagles and white breasted sea eagles. When these wallabies were first introduced to Hayman Island, many were found dead with wounds consistent with eagle attacks. Feral goats have competed with these wallabies for food on Hayman Island. Eradication efforts to eliminate these goats there have been successful.

Proserpine Rock-Wallaby Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

Proserpine rock-wallabies are saltatorial (adapted for leaping), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They rest in their rocky shelters during the day and graze at night in groups of two to six individuals. Four to eight individuals often share the same rock pile, though as many as 35 individuals may do so. These rock shelters offer protection from predators and high temperatures. Proserpine rock-wallabies are cautious and remain near their rock shelters when foraging. In cool weather, they sun themselves near them. Individuals move between colonies when habitat connects rock shelters. Home range of Proserpine rock-wallabies during the dry season is estimated to be 13.6 hectares for males and 12.4 hectares for females. During the wet season, home range is estimated to be 20.1 hectares for males and 9.7 hectares for females. According to one study individual home ranges overlap by 14 percent on average.

Proserpine rock-wallabies are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts). They forage at the edge of forest habitat and are generalist opportunistic feeders, obtaining about 60 percent of their diet from ground dwelling plants, but eat any easily accessible plants, flowers, or seeds. Their diet varies from wet to dry season. In one population, grass made up 54 percent of the diet during the wet season, and 52 percent in the dry season while tree parts, including leaves, made up 34 percent of their diet in the wet season and 32 percent in the dry season. Shrubs increased from seven percent in the dry season to eight percent in the wet season, and vines increased from 0.7 percent in the wet season to eight percent in the dry season. Fungi and forbs (herbaceous flowering plants that are not grasses, sedges or rushes) made up less than one percent of their diet during both wet and dry seasons. Beach scrub is a common food source for the population living on Gloucester Island. Introduced toxic plants pose a possible danger due to the opportunistic nature of Proserpine rock-wallabies.

Little is known about the mating system of Proserpine rock-wallabies. They engage in year-round breeding, bred around once a year and practice embryonic diapause (temporary suspension of development of the embryo). They give birth to one offspring after a gestation period of from 30 to 34 days. Parental care is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth, and emerge from their mother's pouch at around seven months. The weaning age ranges from 10.5 to 11.7 months. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 20.5 to 25.1 months; males do so at 24.8 to 25.2 months.

In favorable conditions, Proserpine rock-wallabies breed year round. Estrus lasts 33 to 38 days. A female can become pregnant immediately after giving birth. When embryonic diapause is used the embryo freezes in development as a blastocyst in response to the lactation hormone prolactin. During weaning, prolactin decreases in the mother, activating the embryonic development of the next young. This cycle allows a mother to give birth a day after the previous joey leaves the pouch permanently.

Nabarlek

Nabarlek (Petrogale concinna) are a small species of rock-wallaby found in northern Australia. Also known as pygmy rock-wallabies, they are shy, nocturnal animals that reside in rocky hollows in sandstone or granite hills, cliffs and gorges and forage in the surrounding area. They are distinguished by a reddish tinge to their mostly grey fur and have a distinct stripe on their cheeks. They move with great speed and agility, with a forward leaning posture and a bushy tail that arches over their back.

Nabarlek are is found are generally found at elevations of 300 to 600 meters (984 to 1968 feet). in two separate areas of Australia: 1) part of the Northern Territory of Australia, including Borda, Augustus, Long, and Hidden Islands, and 2) the northwestern Kimberly area in western Australia. These populations are considered subspecies: Petrogale concinna canescens and Petrogale concinna monastria. [Source: Cassandra Dunham, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Nabarlek are small wallabies. They range in weight from 1.2 to 1.6 kilograms grams (1.5 to 3.5 pounds) and have a head and body length of 31 to 36.5 centimeters (12.2 to 14.4 inches). Their tails range in length from 26 to 33.5 (10.2 to 13.2) centimeters. Their hind feet are 9.5 to 10.5 (3.7 to 4.1) centimeters in length and their ears are 4.1 to 4.5 centimeters (1.6 to 1.8 inches) long. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. The maximum known lifespan of Nabarlek is 17 years. [Source: Cassandra Dunham, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Nabarlek have dull, reddish colored fur with light grey and black marbling. The belly is greyish-white. The tip of tail is black and bushy. The fur is short with a soft, silky texture. The soles of the feet are thickly padded and granulated in order to grip rock; these animals use skin friction rather than large claws to climb. When Nabarlek run they carry their body horizontally with their tail arched high over their back. The teeth of Nabarlek are unique among marsupials. Throughout their life, new molars emerge. The old molars are pushed forward until they eventually fall out in the front of the mouth. The actual number of molars is unknown. As many as nine molars can successively erupt, but there are seldom more than five molars in place at any time. Researchers believe this phenomenon could be an adaptation to the ferns that they eat, because fern tissue is extremely abrasive.

Little is known about Nabarlesk. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Data Deficient. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. The main threats are fires, possibly feral cats, dingoes and humans. Nabarlek reside mainly in two Australia's conservation reserves; Kakadu and Litchfield National Parks.

Nabarlek Behavior, Diet and Reproduction

Nabarlek are shy, gregarious, terricolous (live on the ground), saltatorial (adapted for leaping), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and territorial (defend an area within the home range). They live in groups and occasionally bask in the sun in the morning. The extent of their home range but they sometimes share their territory with short-eared rock-wallabies. [Source: Cassandra Dunham, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Nabarlek communicate with touch and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Captive Nabarlek vocalize during adult female encounters, with the vocalization used in part to establish dominance among females. Vocalization was nearly always given by the defending animal, with each call appearing to have different functional significances. Threat calls are screams, given in response to an attack; sneezes are given at intermediate distances in response to movements of the opponent; coughs are threat calls given in response to an approach; barks are hesitant calls that are generally given at long distances.

Nabarlek are herbivores (eat plants or plants parts) that feed mainly on mainly on grasses, sedges, and ferns in scrubby areas. They tend to not stray very far from the safety of their rock shelter, except at night to forage. During the dry season they rely on the fern Marsilea crenata and feed primarily on grasses during the wet season. Unlike most macropods, adult Nabarlek lack a a gastric sulcus — specialized stomach-like structure where microbial fermentation of food takes place that also facilitates movement of liquid digesta. Captive Nabarlek frequently regurgitating food but scientists say this “this behavior is not analogous to rumination in ruminants and has been termed mercyism”.

Little is known about the mating habits of nabarlek in the wild. They engage in year-round breeding and practice in embryonic diapause (temporary suspension of development of the embryo). Females have an estrus cycle, which is similar to the menstrual cycle of human females. The number of offspring is one. The average gestation period is 30 days. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth and parental care is provided by females. The average weaning age is a little over five months with independence occurring about two weeks after that. On average females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age two years.

Captive Nabarlek females are known to attack males after mating by kicking and biting them in the back of head and neck. If the male don’t lave the run the risk of being killed. Captive nabarleks also display post-partum estrus (return to estrus shortly after giving birth. The estrus cycle lasts 31 to 36 days. Dominant females have a shorter estrus cycle than subordinate one. Females nurse and care for their young until they reach independence. Once the young are weaned, mothers do not tolerate their continued presence. Females drive off young when they attempts to suckle. They may bite at the tail of the young, occasionally causing part of the tail to come off.

Yellow-Footed Rock-Wallabies

Yellow-footed rock-wallabies (Petrogale xanthopu) are perhaps the cutest species of wallaby and kangaroo but unfortunately they are also one of the most theatened. They weigh up to nine kilograms (20 pounds) and are about 60 centimeters (two feet long) and lives during the day in rock outcrops and cliffs in semi-arid pockets of southeastern Australia. They have a face like a teddy bear and a tail like coati mundi. Yellow-footed rock-wallabies ar an ecotourism because they are rare and have such a striking and beautiful appearance. They are difficult to see in the wild but are easy to keep in zoos and parks.

Yellow-footed rock-wallabies have a discontinuous range in different parts of Australia. They are mainly found in: 1) the Flinders and Gawler Ranges and the Olary Hills in the state of South Australia: 2) the Gap and Coturaundee Ranges in New South Wales; and 3) the Adavale Range in Queensland. Their preferred habitats are cliff faces and rocky ramparts on mountain tops, which restricts them to isolated pockets of rocky outcrops, cliffs, and ridges in semi-arid country. Mulga scrub is the dominant vegetation in these areas but the rocky outcrops also provide a wider diversity of vegetation than is found in surrounding areas, which is essential to their diet. [Source: Allison Steinle, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Yellow-footed rock-wallabies are medium-sized wallabies with a stocky build.. They range in weight from two to nine kilograms (4.4 to 19.8 pounds and have a head and body length of 48 to 65 centimeters (1.6 to 2.2 feet). Their long, un-tapered tails from 57 to 70 centimeters, (22.4 to 27.5 inches) long, with an average of 69 centimeters (27 inches). They have large hind feet that are 12 to 17 centimeters (4.7 to 6,7 inches) long and are marked with short claws and thick, course pads. Their average lifespan in captivity is 14.4 years. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females and coloration is different,.

Yellow-footed rock-wallabies have very striking coloring. The head and upper body a brownish-gray color and the rump a brighter gray. And the body increasingly lighter as one moves down. They have a a dark brown streak that runs from their ears to their mid-back. This streak connects to brown and "yellow" patches that are found on the limbs. The face has white stripes running down each cheek with yellow coloring behind the ears. The tail is typically reddish-brown with dark stripes, but is variable. Females, like other marsupials, have a well-developed forward opening pouch and four teats. They are greyish above with white fur below, but the ears, legs, and feet are colored rich red to yellow. They have distinct white cheek and hind stripes, a buff-white side stripe, and a brown mid-dorsal stripe from the crown of their heads to the center of their backs.

It estimated there are less than 10,000 yellow-footed rock-wallabies left in the wild, compared to around 12,000 in the 1990s and 5,000 in the 2000s. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List they are listed as Near Threatened; on US Federal List they categorized as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. Humans have hunted yellow-footed rock-wallabies and macropods in general for their meat, skins, fur and for sport. The main threats to yellow-footed rock-wallabies have been feral goats and domestic sheep which have claimed some of their food and water supplies. Wallabies have also suffered predation from non-native predators, such as red foxes. Conservation efforts have included land acquisition to captive breeding and awareness raising projects. Monitoring programs are in place that keep track of population sizes. Red fox and goat eradication have helped some populations come back.

Yellow-Footed Rock-Wallaby Behavior, Diet, Reproduction

Yellow-footed rock-wallabies are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and nocturnal (active at night). They spend their days hidden in rock crevices and caves, occasionally sunbathing on a rock, and come out at night to forage, feeding on local vegetation as near as possible to their hiding place. In captivity, they are sometimes active during the day. Yellow-footed rock-wallaby are very sure footed. They have the same posture as larger kangaroos but are able to maneuver around cliffs and rock ledges like mountain goats. They often get around by leaping from rock to rock. Jumps of up to four meters in length have been measured. Yellow-footed rock-wallabies even have the ability to climb up steep cliff faces and tree trunks. [Source: Allison Steinle, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Yellow-footed rock-wallabies are herbivores (animals that primarily eat plants or plants parts). They are both grazers (eat grass or other low-growing plants) and browsers (eat non-grass plants such as bushes and tree parts higher up off the ground). In the wet season, their diet consists mainly of grasses. As conditions become increasingly dryer, they shift to the leaf fall of shrubs and trees. During drought, leaf fall is their staple food. Yellow-footed rock-wallabies also have the unique ability to consume over ten percent of their body weight in water in about seven minutes. This allows them to utilize the infrequent summer rainstorms that occur where they live as as opposed to the salty creek runoff that other species in the area depend on. |=|

Yellow-footed rock-wallabies usually have one offspring after a 31 day gestation period. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at around 18 months; males do so at 19½ months. According to Animal Diversity Web : Given good nutrition and living conditions, Yellow-footed rock-wallabies breed all year long. In fact, females ovulate, mate, and conceive within a day of giving birth, making it very common for them to be pregnant 365 days a year. Their estrus cycle lasts from 30 to 32 days. The embryo will develop and be born after the removal of the previous young. Pouch life then lasts anywhere from six to seven months.

Short-Eared Rock-Wallabies

Short-eared rock-wallabies (Petrogale brachyotis) are found in northern Australia, in the Kimbereley region of northernmost Western Australia and Arnhem Land eastward along the Gulf of Carpentaria in the Northern Territory to the eastern boundary of the Australian Shield, including Groote Eylandt. They favor rocky areas or boulder-strewn outcrops, — on low, rocky hills, cliffs, and gorges — typically near forests, woodlands, or savannahs. Short-eared rock-wallabies are larger than their three closest relatives, eastern short-eared rock-wallabies, nabarlek and monjon. Short-eared rock-wallabies are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. While other species of Petrogale have been threatened by introduced species, such as feral rabbits and feral goats, the populations of short-eared rock-wallabies have not declined is due, in part, to the numerous island populations of northern Australia which have been unaffected by introduced species.

Short-eared rock-wallabies range in weight from four to five kilograms (8.8 to 11 pounds) and range in length from 83 to 107 centimeters, with the average adult size being 97 centimeters long. They have an extremely long, bushy, and thickly-haired tail which is used primarily for balancing. The ears of Short-eared rock-wallabies are no more than half the length of their heads, hence their name. Fur color ranges from light grey and almost white in western populations to dark grey and brown in eastern populations. The fur is uniform in color across their back and can have variable whitish margins. Short-eared rock-wallabies have well-padded hind feet, with the soles being roughly granulated. This these animals a secure grip on rocky surfaces. The central hind claws are short. Female rock-wallabies have a forward-opening pouch with four mammae. [Source: Jesse Null, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Short-eared rock-wallabies mainly feed on grasses. In dry seasons they can live for long periods of time without water by feeding on the succulent bark and roots of various trees within their habitat. They are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and primarily nocturnal but may come out during the day to sun themselves on rocks Little is known about the behavior and reproductive habits of short-eared rock-wallabies. Rock-wallaby females are polyestrous, with an average estrus cycle of 30 days and a gestation period of 30 days. They give birth to a single altricial young that migrate from the end of the birth canal to a pouch that houses the nipples. Young can spend anywhere from six to eight months in the mother's pouch nursing. Female rock-wallabies reach sexual maturity at approximately 18 months, while males reach sexual maturity at approximately 20 months.

Black-Footed Rock-Wallabies

Black-footed rock-wallabies (Petrogale lateralis) are also known as black-flanked rock-wallabies and warru. They are sometimes referred to as the "West Australian rock-wallabies" even though their range is not confined to West Australia. They are also found in northern South Australia and the southern parts of the Northern Territory. Like other rock-wallabies species, they live on rock piles, cliffs, and rocky hills and make shelters near caves or cliffs and are often found in very arid areas where water is scarce. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, black-footed rock-wallabies are listed as Near Threatened Populations tend to be isolated and fragmented. [Source: Joshua Seinfeld, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Black-footed rock-wallabies range in weight from 3.1 to 7 kilograms (6.8 to 15.4 pounds). Like all rock-wallabies, they have thick and padded hind feet with granulated soles that provide traction on rocky terrain. Black-footed rock-wallabies have a thick and soft grey-brown coat. Their face is dark and grey with a light stripe on the cheek. The various subspecies of black-footed rock-wallabies differ in body markings and size. In most subspecies, females are 70 to 85 percent the weight of males the same age.

Black-footed rock-wallabies are shy, nocturnal herbivores. They feed mainly on grass and herbs and do not need to drink much water to survive and sometimes lives in areas where no permanent water source is available. Black-footed rock-wallaby live in groups of between ten and a few hundred members. They are fairly inactive during the hottest hours of the day, seeking shelter in caves, but they do bask in the sun to warm themselves in the morning after a cold evening and sometimes also in the early evening. They are most active during early evening when they leave their shelter to feed on plants.

All rock-wallaby species breed continually. The gestation period and estrus cycle are both about 30 days. As with other marsupials, new born rock-wallabies are very undeveloped and suckle inside their mother's pouch. Unlike other kangaroos and wallabies, young rock-wallabies that have left the pouch but are not yet weaned are often left in a sheltered area while their mother goes off to feed. This may be because of the treacherous terrain in which the rock-wallabies live.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025