Home | Category: History and Religion / Maori

MĀORI AT THE TIME OF THE EUROPEAN ARRIVAL

There were between 100,000 to 300,000 Māori living in New Zealand when the first Europeans arrived in the 17th century. The Māori population was divided into 40 tribes that lived in and around hilltop forts with ditches, strong palisades and large food storage chambers. The Māori had no not developed siege warfare so these forts were regarded as secure. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

When Captain Cook visited New Zealand in 1769 the indigenous population was probably between 200,000 and 250,000. The population declined after contact with Europeans. In the early 19th century, at the end of their war against European encroachment, the Māori in New Zealand numbered about 100,000. The number later dwindled to 40,000.

In the 17th century, it is believed that lifespan for the average Māori was only 35 years. They were taller than the Europeans, with Māori men averaging 175 centimeters compared to 160 centimeters for European men living at that time.

In 2017, Archaeology magazine reported; The remains of a Māori village dating to between 1600 and 1800 were uncovered during a road construction project near Papamoa on the country’s North Island. Several hundred archaeological features of the settlement were exposed, including crop storage pits, cooking pits, and postholes from several large Māori communal houses known as whares. The discovery is not only providing researchers with new insights into the layout and organization of native communities, but is also revealing aspects of daily life. [Source: Jason Urbanus Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, lumbering, seal hunting, and whaling attracted a few European settlers to New Zealand. In the 1790s-1800s, the main ingredients of Māori-European (Pakeha) contacts were whaling, timber and the spread of disease.

In 1840, there were about 2,000 Europeans and 115,000 Māori in New Zealand. By this time the Māori were trading crops and land with the Europeans in return for firearms, which fueled intense intertribal warfare. In 1840, the United Kingdom established British sovereignty through the Treaty of Waitangi signed that year with Māori chiefs. In the same year, selected groups from the United Kingdom began the colonization process.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS LIKE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST EUROPEAN SETTLERS IN NEW ZEALAND ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI KINGS AND QUEENS: KINGITANGA, LIVES, REIGNS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRIEF HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND: NAMES, THEMES, HIGHLIGHTS, A TIMELINE ioa.factsanddetails.com

DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA BY EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

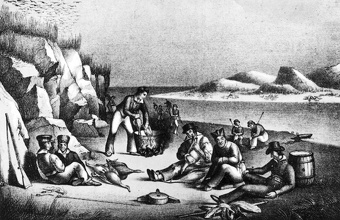

Impact of Sealers on the Māori

Seals and sea lions were hunted another for their meat, oil and fur. Leather is sometimes made from seals. Commercial sealers traditionally drove the seals to a designated area and killed them with blow to soft parts of their skulls. Sealing — the hunting of seals — was widely practiced in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th century. [Source: New Zealand History 1800 -1900, A blog to assist the students in Level 3 NCEA History at Wellington High School, February 28, 2008 ]

In New Zealand, the first Sealers set up camp in Dusky Sound (Fiordland) in 1792. Mainly ex-convicts, they were outfitted and supplied by entrepeneurs based in Port Jackson (Sydney). The job was simple. Kill as many Fur Seals as possible, skin them, cure the hide with salt and wait to be picked up. A good crew could return to Sydney with several thousand skins.

According to a blog on New Zealand history: Sealers were a rough and ready group. They settled in small groups around the southern coasts of both Islands. Sparsley populated by Māori their interaction remained relatively light. Most sealing operations were centred on the south coast of the North island, and both coasts of the South Island. These areas were lightly populated by Māori especially the South Island. This did not mean that their impact was not important but the gangs were not settlers. They lived close to seal colonies were there for a matter of weeks or months and left. They might return but it was an itinerant lifestyle and was often a different group of men. They rarely carried any trade goods thus there was little incentive for Māori to interact with them in anything more than a cursory nature. The impact of this interaction is limited by the areas that sealing took place.

The greatest fear of all Sealers were the Māori. The thought that they might end up in a cooking pot terrorised them. Several gangs did disappear, probably to attack by local tribes. In 1817 Captain Kelly of the 'Sophia' was attacked by Māori. He and his crew fought them off then attacked their settlement. Captain Riggs of the 'General Gates' had a bad reputation in Sydney and it was no surprise that he apparently upset Māori in southern New Zealand who attacked two of his gangs, killing and eating them both over several days in 1823 and later in 1824. James Caddell was one sealer who was captured by Māori but who managed to become an accepted member of the tribe, becoming a Pakeha-Māori. In the 1820's a gang was attacked and John Boultbee recorded their escape and the help afforded by more friendly Māori nearby.

For more on Sealers See FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Māori Versus the Colonists

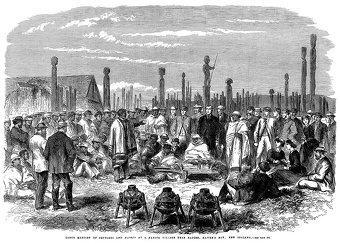

Large meeting of settlers and Māori at a Māori village near Napier, Hawke's Bay, New Zealand; Illustration for The Illustrated London News, October 1863

In 1835, some Māori iwi from the North Island declared independence as the United Tribes of New Zealand. Fearing an impending French settlement and takeover, they asked the British for protection.

According to “CultureShock! New Zealand”:The Māori people describe themselves as the tangata whenua, the people of the land, and they are the original settlers in New Zealand. The first non-Polynesian settlers along the shores of New Zealand were sealers and whalers. Many of these seafarers took Māori ‘wives’ and their offspring would be the earliest New Zealanders of mixed lineage. With the arrival of increasing numbers of traders and permanent settlers, intermarriage between Māori and Pakeha (Europeans) became more common.[Source: Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Marshall Cavendish International, 2009]

Most Māori today will tell you of a European forebear in their whakapapa (genealogy), and many of them are proud of their European tupuna (ancestors). The sealers and whalers were followed by missionaries, agriculturalists, explorers, merchants and adventurers.

The rapid growth in the Pakeha population alarmed Māori chiefs and tensions escalated. The compromise between the British government and the Māori chiefs culminated in the Treaty of Waitangi (See Below) The influx of European settlers pressured the colonial administrators of New Zealand to make more land available. The Māori had reason to feel threatened. The Europeans had brought with them not just ‘civilisation’, but also firearms, alcohol and diseases against which the Māori population had little or no immunity.

Musket Wars and the Trade of Tattooed Heads

Mokomokai, or Toi moko, are the preserved heads of Māori, with faces that have been decorated by ta moko tattooing. They became valuable trade items during the Musket Wars, a series of inter-tribal conflicts raged across New Zealand that were fueled by new weapons that Europeans brought to the country. The conflict is believed to have led to the deaths of 20,000 people. And as tribes eagerly sought to purchase guns, toi moko became a valuable form of currency. [Source: Brigit Katz, Smithsonian, July 16, 2018]

“Tribes in contact with European sailors, traders and settlers had access to firearms, giving them a military advantage over their neighbors,” the blog Rare Historical Photos explains. “This gave rise to the Musket Wars, when other tribes became desperate to acquire firearms too, if only to defend themselves. It was during this period of social destabilization that mokomokai became commercial trade items that could be sold as curios, artworks and as museum specimens which fetched high prices in Europe and America, and which could be bartered for firearms and ammunition.”

The situation got so out of hand that Māori began tattooing and killing their slaves so their heads could be exchanged for guns, according to Catherine Hickley of the Art Newspaper. Collectors would survey living slaves, letting their masters know which ones they wanted killed. People with tattooed faces were attacked. The trade of toi moko was outlawed in 1831, but it continued illegally for nearly a century after that.

See Mokomokai — Māori Smoked Tattooed Heads Under MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES, TATTOOS, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Treaty of Waitangi

Concerned about the impact of firearms on their traditional way of life, Māori chiefs approached British government representatives in New Zealand with the idea of establishing a treaty that would stem the flow of settlers, end tribal warfare and maintain law and order. The British were anxious to make a deal as a way of preventing France or the United States from taking over New Zealand.

The ensuing agreement, the Treaty of Waitangi — signed on February 6, 1840 at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by representatives of the British crown and 500 Māori chiefs — promised the Māori the same rights as British subjects and protected their land and the rights of chiefs in return for giving the British crown the right to buy Māori land. There was also a clause that guaranteed Māori undisturbed ownership of their forests, fisheries, lands, and other possessions.

The treaty was signed at a time when Victorian humanitarian and the evangelical movement had a major influence on British foreign policy. It was originally intended to avoid "the disasters and the guilt of conflict with the Native Tribes," and was supposed to ensure that the Māori didn't suffer the same fate as native Americans in the United States, aborigines in Australia and Bantus in South Africa.

The British negotiated their protection in the Treaty of Waitangi, which was eventually signed by more than 500 different Māori chiefs, although many chiefs did not or were not asked to sign. In the English-language version of the treaty, the British thought the Māori ceded their land to the UK, but translations of the treaty appeared to give the British less authority, and land tenure issues stemming from the treaty are still present and being actively negotiated in New Zealand. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

According to the Treaty of Waitangi the Māori chiefs that signed it ceded some political powers to the British but maintained indigenous rights in perpetuity. The Māori chiefs who signed did so on behalf of their tribes but not all of them did. Māori land was to be sold directly to the British Crown to prevent unscrupulous purchasers from exploiting the Māori,

Waitangi Day, which commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, is regarded by many as New Zealand’s national day. Nonetheless, the treaty was not honored and terms that were supposed to benefit the Māori were instead used to screw them and annex New Zealand. Some Māori land was confiscated but most of it was sold and acquired through negotiated purchases. As new settlers arrived, the appetite of the Europeans for land increased.

Māori After the Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi promised the Māori that they would keep their lands and property and have equal treatment under the law as British subjects. However, the British later seized Māori lands and made the people move to reservations.[Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999]

The UK declared New Zealand a separate colony in 1841 and gave it limited self-government in 1852. Many settlers came to New Zealand in the 1830s, 40s and 50s when there were minor gold rushes in the Auckland area, the Coromandel Mountains and the South Island. Many missionaries also arrived during those years. Another gold rush occurred in 1861.

Despite occasional clashes, relations between Māori and Pakeha (New Zealand Europeans) were generally peaceful during the early colonial period. Many Māori communities established thriving enterprises, producing and trading food and other goods for both local and overseas markets. When conflict did occur—such as the Wairau Affray, Flagstaff War, Hutt Valley Campaign, and Wanganui Campaign—it was usually limited in scope and ended through negotiated peace agreements. [Source: Wikipedia]

For the Māori there was a period of rapid acculturation that lasted until 1860. However, the Māori population felt threatened by the ever increasing number of Pakeha demanding more and more land. Many Māori refused to sell their land and live under British law. These sentiments produced tensions that mounted and erupted into rebellions and wars in the North Island in the 1860s.

Ngāti Maniapoto is an important iwi (tribe) from the Waikato-Waitomo region of New Zealand's North Island, belonging to the Tainui confederation. The tribe is named after its ancestor, Maniapoto, and has a history of successfully defending its territory, particularly the King Country region, and preserving its culture. According to The Guardian: In 1840, Ngati Maniapoto was a strong independent iwi with expanding trade connections among the growing Pakeha (New Zealand European) population. But in the decades following, their tribal structures were eroded as the crown confiscated land, grossly underpaid the iwi for purchased land and deprived the iwi of their turangawaewae (foundation) through compulsory acquisitions for public works. [Source: Eva Corlett in Wellington, The Guardian, September 23, 2022]

How Whites Took Māori Land

Many early laws affecting Māori dealt with the ownership and sale of Māori land. The Land Claims Ordinance of 1841 established the Native Protectorate Department to prevent settlers from fraudulently taking land from Māori. From 1840, the demand for land from Europeans increased dramatically as the number of settlers swelled. According to Article Two of the Treaty of Waitangi, only the Crown could purchase land from Māori. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

However, Governor Robert FitzRoy relaxed this rule in 1844, allowing direct purchases by settlers. However, under the Native Land Purchase Ordinance of 1846, Governor George Grey stopped such direct sales, and agents of the Crown working for the Native Land Purchase Commission purchased as much Māori land as possible. The strategies they employed to convince sellers were often dubious and included: 1) Targeting the weaker members of tribesl 2) forcing sales under threat of military action; 3) purchasing from individuals rather than groups that owned land rights collectively; and 4) purchasing from non-owners. They also promised reserves for Māori on tracts of land that they sold, but then failed to provide them or provided reserves that were smaller than promised or on unsuitable land. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

According to the New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863, the land of any tribe "engaged in rebellion" against the government could be confiscated. Altogether, 1.3 million hectares of Māori land were confiscated, often inconsistently. The middle and lower Waikato Kingitanga tribes lost nearly all their land, while the Ngāti Maniapoto, active combatants in the Taranaki and Waikato wars, lost very little. This was because the fertile Waikato lands were better suited for European settlement.

Māori who claimed their land had been unfairly confiscated could take their case to a compensation court within six months. Sometimes, by the time the court ruled in favor of the Māori claimants, their confiscated land had already been sold. The court might then award them barren or marginal land as compensation. Other confiscated land was returned to people who were not the original owners.

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 established the Native Land Court. This freed up more land for purchase by settlers because it individualized Māori land titles. Justice Minister Henry Sewell described the court's purpose as "to bring the great bulk of the lands in the North Island ... within the reach of colonization."

Māori Rebellions

Different traditions of authority and land use led to a series of wars from the 1840s to the 1870s fought between Europeans and various Māori iwi. Along with disease, these conflicts halved the Māori population. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

By the 1860s, however, the rapid growth of the settler population and increasing disputes over land purchases led to the New Zealand Wars. These were fought between the colonial government, supported by British and allied Māori forces, and various Māori iwi defending their territories. Following the wars, the government confiscated large areas of Māori land as punishment for what it termed “rebellions,” and settlers soon occupied these confiscated lands. [Source: Wikipedia]

The years 1860-1865 saw many battles between the Māori and the government of New Zealand, mainly over questions of land rights and sovereignty. Expanding European settlement led to conflict with Māori, most notably in the Māori land wars of the 1860s fought between the Māori and a combination of British administration forces and settlers. British and colonial forces eventually overcame determined Māori resistance. During this period, many Māori died from disease and warfare, much of it intertribal.

According to The Telegraph: In 1864, during a Māori uprising against the British, Captain PWJ Lloyd was killed, and his severed head became the divine conduit for the angel Gabriel, who, among other fulminations, had not one good word to say about the Church of England. [Source: Simon Ings, The Telegraph, January 7, 2022]

There were two major rebellions: one in 1860 and another from 1863 to 1881. The Māori jade clubs and spears were no match for British guns and both rebellions were put down. When the Māori armed themselves with firearms instead of traditional weapons, intertribal raids resulted in more deaths and casualties. When the fighting was over the Māori were a defeated and largely dispossessed people. Smaller conflicts continued in the following decades, including the Parihaka invasion of 1881 and the Dog Tax War of 1897–98.

Te Kooti and Te Kooti’s War

Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki — commonly known simply as Te Kooti — was a significant 19th century Māori figure — who led and rebellion and founded the Ringatu church. Te Kooti’s early life was turbulent. Known for his rebellious temperament, he was once nearly buried alive by his father and later led a band of lawless companions who raided settlements along the East Coast. [Source: Wikipedia]

After being expelled by his hapu, he became a successful trader sailing between Gisborne and Auckland. When his people joined the Pai Marire (“Hauhau”) movement, Te Kooti initially sided with government forces but was accused of supplying gunpowder to the Hauhau and arrested under martial law. He was exiled to the Chatham Islands with other prisoners during the conflicts of the 1860s.

While imprisoned, Te Kooti experienced a spiritual transformation. Immersing himself in the Bible—particularly the Old Testament—he blended its teachings with Māori cosmology and ritual. He began conducting services, incorporating dramatic performances that drew on both biblical symbolism and traditional Māori spirituality. Using phosphorus to make his fingers glow, he performed visionary displays and took on the form of a ngarara (lizard), a creature of great tapu significance, while speaking in tongues.

His teachings were delivered orally and often framed as riddles or challenges. One famous test involved a white stone, which his followers ground into powder and ate, symbolizing their acceptance of divine wisdom. Te Kooti taught that white quartz stones represented the Lamb of God and incorporated them into Ringatū symbolism. He also declared that the Archangel Michael had commanded him to lead his people against the colonial government—whom he equated with Satan. Drawing parallels between the biblical Israelites’ exile and the Māori loss of land, he positioned himself as a prophet leading his people toward deliverance. His charisma and scriptural knowledge persuaded many prisoners to abandon the Pai Marire faith and embrace his new religion.

In 1868, Te Kooti and his followers seized a ship, escaped from the Chatham Islands, and returned to the North Island. Declaring himself “King of the Māori,” he initiated what became known as Te Kooti’s War, a four-year campaign against colonial forces marked by cycles of revenge (utu) and violent retribution. Though many atrocities occurred, there is no evidence that Te Kooti himself directly participated in acts of torture or murder. His reported ability to elude capture—sometimes attributed to the supernatural powers of his horse—became part of Ringatū legend.

As the conflict dragged on, Te Kooti’s following dwindled under relentless pursuit by Major Gilbert Mair and his largely Māori forces. Eventually seeking refuge in the King Country, Te Kooti was granted sanctuary by the Māori King, Tawhiao, though tensions arose over Te Kooti’s unorthodox behavior, including his drinking, polygamy, and defiance of the King’s authority. Their strained relationship reflected a deeper division between Te Kooti’s prophetic, visionary style and the King Movement’s conservative discipline.

Decline of the Māori in the Late 19th Century

Most of the Māori armed resistance ended by 1872 and resulted in loss by the Māori of much land. There were mass seizures of Māori land and other injustices by settlers and the British administration. The creation of the Native Land Court further accelerated the loss of Māori land by converting communal ownership into individual titles, facilitating widespread sales to European settlers and advancing colonial assimilation policies. By 1890, less than one sixth of New Zealand's land remained in Māori hands and a quarter of that was leased to Europeans under terms that were favorable to the Europeans.

By the turn of 20th century the Māori were almost wiped out by diseases introduced by Europeans for which they had no resistant. At this time, , both Pakeha and Māori widely believed that the Māori population would cease to exist as a separate race or culture and become assimilated into the European population. From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, New Zealand society instituted various laws, policies, and practices that induced Māori to conform to Pakeha norms. Notable examples include the Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907 and the suppression of the Māori language in schools, which was often enforced with corporal punishment. [Source: Wikipedia]

By the time of the 1896 census, New Zealand's Māori population was 42,113, down from around 200,000 in 1840, while the European population had grown to over 700,000. It took years for the Māori to regain their numbers and morale. Attempts have been made to address the injustices perpetrated in the 1860 wars and their aftermath, particularly with regard to land.

Māori in the Early 20th Century

The Māori gradually recovered from population decline and, through interaction and intermarriage with settlers and missionaries, and adopted many aspects of European culture. By 1900 their population slide had reversed and the Māori began to play a more active role in New Zealand society. They received Permanent Māori seats in the national legislature, and most discriminatory laws were repealed. The Māori are now a legally recognized minority group and they receive special legal and economic considerations on these grounds.

Largely through the efforts of their own chiefs, the Māori reemerged as an economically self-sufficient minority in New Zealand. They maintain their own cultural identity apart from the general New Zealand community, while at the same time they have representatives in parliament.

The origins of the Māori pride movement can be traced back to Sir Apirana Ngata (1874–1950), a gifted orator who established land corporations in the 1930s, revitalized traditional Māori culture, and helped establish the Māori 28th Battalion in World War II. About 17,000 Māori volunteers fought in World War II, mostly in the Mediterranean.

Ngata was born in Te Araroa on the East Coast, he became the first Māori to earn a university degree in New Zealand. After graduation, Ngata returned to his tribal territory (Ngati Porou) and became active in trying to improve the social and economic conditions of Māori. He was elected to Parliament in 1905 and appointed to the Cabinet in 1909. Much of the legislation, such as the Native Land Act, and government bodies, such as the Māori Purposes Fund Control Board and the Board of Māori Ethnological Research, owe their existence to Ngata’s involvement. He promoted Māori culture through his writing and active advocacy of Māori cultural practices. Despite experiencing mixed political fortunes throughout his career, Sir Apirana laid the foundation for the Māori cultural renaissance of the 1950s. His image is on the New Zealand $50 bill. [Source: Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Marshall Cavendish International, 2009]

Around 17,000 Māori volunteers fought along side some 157,000 troops from New Zealand in World War II (1939–45). New Zealand soldiers distinguished themselves at Tobruk and El Alamein in North Africa. During a World War II battle on the island of Crete, Māori units reportedly sent German soldiers running for the hills with their fierce war cries, chants of "Ka mate, ka mate" ("it is death, it is death!"), and haka war dances, with eyeball rolling and tongue sticking out.

Māori Since World War II

Since World War II, New Zealand government policies have been more favorable to the Māori. In recent decades, the government of New Zealand has acknowledged its responsibility to the Māori after a series of protests and court rulings. Their numbers reached 300,000 in the 1960s and 500,000 in the 1990s thanks mainly to modern medicine, increased resistance to disease, a high birth rate and intermarriage with whites. In recent years, a big effort has been made to revive traditional Māori culture, keep the Māori language alive and foster Māori pride. Since the 1960s there has been a move to revitalize the Māori language and the Māori are attempting to preserve their cultural heritage while living side-by-side with the "Pakeha" (New Zealanders of European descent).

Māori claims and grievances were not taken seriously until the 1970s, when there were protests, calls for apologies and restitution, and a rise in Māori assertiveness and consciousness. In 1975, the New Zealand government established the Waitangi Tribunal to address Māori claims, many of which were based on how they had been screwed by the Waitangi Treaty of 1840. In the 1980s the Māori started organizing themselves politically. One activist at the time told National Geographic: "We had these islands, we lost them to the Europeans, and now we want them back." One of their first moves was to get to a hold of 40,000 acres of land in Mount Aspiring National Park to, among other things, protect a 25 ton boulder of jade.

In recent decades, Māori have become increasingly urbanized and have become more politically active and culturally assertive.Since the 1970s the Māori and the government have negotiated several settlements of land and other claims lodged by various Māori groups; the claims date back to the 19th century, when land was seized by British colonists in violation of the Treaty of Waitangi. In October 1996, the government agreed to a settlement with the Māori that included land and cash, with the Māori regaining some traditional fishing rights. The Māori have been striving to revive aspects of their traditional culture, reclaim artifacts of their cultural history from foreign museums, and regain their ancestral homelands. [Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999]

For Information on Recent History See MĀORI GOVERNMENT: HISTORY, POLITICS, CHIEFS, TRADITIONAL LAW ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New Zealand Tourism Board, Wikipedia, Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet, BBC, CNN and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025