FIRST EUROPEANS TO DISCOVER AUSTRALIA

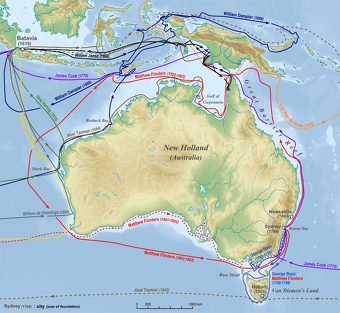

A) 1606 Willem Janszoon (black); B) 1606 Luís Vaz de Torres (orange); C) 1616 Dirk Hartog (Green); D) 1619 Frederick de Houtman (yellow); E) 1642 Abel Tasman (brown); F) 1696 Willem de Vlamingh (greyish blue); G) 1699 William Dampier (dark blue); H) 1770 James Cook (Light blue); I) 1788 Arthur Phillip (pink); J) 1797–1799 George Bass (blue); K) 1801–1803 Matthew Flinders (red)

Australia is remarkable for the number of explorers who missed it or found it but didn’t realize they had found it. Among the later were Dutchmen Dirk Hartog who was blown into Western Australia in 1616 and didn’t understand the significance of where and Abel Tasman, who managed to discover Tasmania in 1642 and sail around Australia without finding it. Up until the 16th century, there was a belief that a “Great South Land” existed (See Terra Australis Below). Some think that the Portuguese reached Australia before 1600 but these theories are difficult to prove. The 1567–1606 Spanish voyages from South America stopped at islands to the east before reaching Australia. [Source: Wikipedia +; Ilsa Sharp, “CultureShock! Australia”]

Dutch, Portuguese, and Spanish explorers and fortuneseekers were all active in east Asia and making their first probes into the Pacific Ocean in the 16th century. The first recorded explorations of what is now Australia took place early in the 17th century, when Dutch, Portuguese, and Spanish explorers explored bits and pieces of the continent and the area around it. None took formal possession of the land, and not until 1770, when Capt. James Cook charted the east coast and claimed possession for Great Britain was any major exploration or mapping done. Up the early 19th century, Australia was known as New Holland, New South Wales, or Botany Bay. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, 2007]

The first European to definitely see Australia was Willem Janszoon who in February 1606 reached the Cape York Peninsula and thought it was part of New Guinea. Also in 1606 (June to October) Luis Váez de Torres of the Quiros expedition from South America followed the south coast of New Guinea and passed through the Torres Strait without recognizing Australia. His voyage, and therefore the separation between Australia and New Guinea, was not generally known until 1765, shortly before Captain Cook’s voyages. +

Later, after Cook's death, Joseph Banks recommended sending convicts to Botany Bay (now in Sydney), New South Wales. A First Fleet of British ships arrived at Botany Bay in January 1788 to establish a penal colony, the first colony on the Australian mainland. In the century that followed, the British established other colonies on the continent, and European explorers ventured into its interior.

Related Articles:

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com ;

EUROPEANS DISCOVER THE PACIFIC AND OCEANIA ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

MAGELLAN AND THE FIRST VOYAGE AROUND THE WORLD ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN THE PACIFIC: DESCRIPTIONS, EVENTS AND PLACES VISITED ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST EUROPEAN IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, SETTLERS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

EUROPEANS IN THE PACIFIC IN THE 1800S: WHALERS, MISSIONARIES, COPRA AND FORCED LABOR ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Terra Australis and Early European Perceptions of a Southern Continent

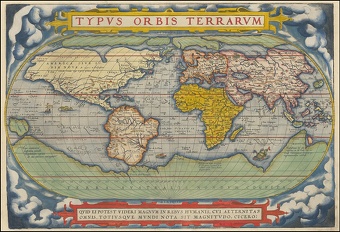

1570 map by Abraham Ortelius depicting Terra Australis Nondum Cognita (Southern Land Not Yet Known), a large continent on the bottom of the map

Australia and Antarctica were the last major landmasses discovered by Europeans. During Byzantine times (A.D. 300 to 1400) many people believed the world was round, but the southern hemisphere they thought was occupied by land known as Antipodes, where "men's feet were higher than there heads, trees grew upside-down, and rain fell upwards." Scholars debated whether or not it was possible for the creatures on Noah's Ark to reach Antipodes.

Terra Australis (Latin: 'Southern Land') was a hypothetical continent first suggested in ancient times. Appearing on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries, its existence was not based on any survey or observation, but rather on the idea the world needed to be balanced and the large land masses in the Northern Hemisphere needed to be equalized by land masses in the Southern Hemisphere. This idea of balancing land was first documented on a A.D. 5th century map by Macrobius, who uses the term Australis on his maps. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the A.D. 2nd century, Ptolemy believed that the Indian Ocean was enclosed on the south by land and lands in the Northern Hemisphere should be balanced by land in the south. The famous Roman statesman and writer Cicero (106-43 B.C.) used the term cingulus australis ("southern zone") in referring to the Antipodes in "Dream of Scipio". Terra means “Land” in Latin, and thus Terra Australis came into being, meaning “Land of the South”.

Legends of Terra Australis Incognita — the "Unknown land of the South" — date back to antiquity and were commonplace in medieval geography. Ptolemy's maps, which were well known in Europe in the Renaissance, did not depict the continent, but they did show an Africa which had no southern oceanic boundary and extended all the way to the South Pole. The first known depiction of Terra Australis on a globe was on Johannes Schöner's lost 1523 globe. He called the continent Brasiliae Australis. In his 1533 tract, Opusculum geographicum he wrote: Brasilia Australis is an immense region toward Antarcticum, newly discovered but not yet fully surveyed, which extends as far as Melacha and somewhat beyond. The inhabitants of this region lead good, honest lives and are not Anthropophagi [cannibals] like other barbarian nations; they have no letters, nor do they have kings, but they venerate their elders and offer them obedience; they give the name Thomas to their children [after St Thomas the Apostle]; close to this region lies the great island of Zanzibar at 102.00 degrees and 27.30 degrees South.

Some explorers were seeking a mythical continent called Locac (Locach). Marco Polo said that the great Genghis Khan described this Oriental version of Eldordo as a land where "gold is so plentiful that no one who did not see it could believe it." The journey of Dutchman Abel Tasman around Australia and the circumnavigation of Australia by Matthew Flinders in 1801-1803 showed once and for all that Australia wasn't the mythical continent of Lokac.

The first depiction of Terra Australis on a globe was probably on Johannes Schöner's lost 1523 globe on which Oronce Fine is thought to have based his 1531 double cordiform (heart-shaped) map of the world. On this landmass he wrote "recently discovered but not yet completely explored". The body of water beyond the tip of South America is called the "Mare Magellanicum", one of the first uses of navigator Ferdinand Magellan's name in such a context.

Early Dutch Explorers

Most of the first Europeans to explorers Australia were Dutch. They mapped the western and northern coasts and named the continent New Holland but made no attempts to permanently settle it.

Thirty Dutch navigators explored the western, northern and southern coasts of in the 17th century. In 1616, Dirk Hartog was blown into the west coast of Australia and scoped it out a bit. Frederick de Houtman did the same in 1619. In 1623 Jan Carstenszoon followed the south coast of New Guinea, missed Torres Strait and went along the north coast of Australia. In 1643, Abel Tasman missed Australia, found Tasmania, continued east and found New Zealand , turned northwest, missed Australia again and sailed along the north coast of New Guinea. In 1696, Willem de Vlamingh explored the southwest coast.

It is at least plausible that early Portuguese explorers sighted Australia but the European who is credited with discovering it is Dutch captain Willem Janszoon, in 1606. From about 1611, the standard Dutch route to the East Indies (present-day Indonesia) was to follow the roaring forties, which ran south of Indonesia, as far east as possible and then turn sharply north to Batavia (present-day Jakarta) on the Indonesian island of Java. Since it was difficult to know longitude some ships reach the west coast of Australia or be wrecked on it.

The Dutch followed shipping routes of the Dutch East Indies used for trading spices, china and silk. There are many old shipwrecks of the west coast of Australia. Some of them belong to Dutch East India Company that missed the turn Batavia. A slight miscalculation could result in a terrible tragedy. One of first ships to go down was the “Batavia”. It ran aground in 1628. By the time help arrived three months later the crew had mutinied, resulting in the deaths of 120 people.

Many early Dutchmen in Australia were were shipwrecked on the rugged western coast. In 1616 Dirk Hartog landed on an island off Shark Bay and nailed a plate into a tree and left. In 1667 another Dutch explorer arrived and removed the plate and replaced it with another and left. In 1622–23 the Dutch ship Leeuwin made the first recorded rounding of the south west corner of the continent, and gave her name to Cape Leeuwin. In 1627 the south coast of Australia was accidentally encountered by Dutch-French navigator François Thijssen. He named and named it Land van Pieter Nuyts, in honour of the highest ranking passenger, Pieter Nuyts, the Councillor of India. In 1628 a group of Dutch ships was sent by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies Pieter de Carpentier to explore the northern coast. These ships made extensive examinations, particularly in the Gulf of Carpentaria, named in honour of de Carpentier. In 1696, Willem de Vlamingh explored the southwest coast of Australia and discovered Perth’s Swan River.

The Dutch made no effort to settle or claim Australia. Early Dutch navigators considered Australia to be wasteland and felt it had few commercial possibilities.

Willem Janszoon, the First European to Discover Australia

The first Europeans to definitely sight and land on Australia were the crew of the ship Duyfken captained by Dutchman Willem Janszoon who in February 1606 reached the Cape York Peninsula and thought it was part of New Guinea. Janszoon was scouting the region around the Spice islands in present-day Indonesia, he landed on the northern and western coasts of the Australia.

The crew of the Duyfken landed on the western side of Cape York Peninsula. They were the first to chart the Australian coast and meet with Aboriginal people. Janszoon sighted the coast of Cape York Peninsula in early 1606, and made landfall on February 26 at the Pennefather River near the modern town of Weipa on Cape York. Also in 1606, a few months after Janszoon, the Spaniard Luis Vaez de Torres may have sighted Australia while sailing though the Torres Strait that bears his name today between Cape York and New Guinea.

Janszoon charted some 320 kilometers (200 miles) of the coastline, which he thought was a southerly extension of New Guinea. He crossed the eastern end of the Arafura Sea into the Gulf of Carpentaria, without being aware of the existence of Torres Strait, which separates Australia from New Guinea .

The area Janszoon explored was very swampy and the people were inhospitable. Ten of Janszoon’s men were killed on various shore expeditions — several by Aboriginal spears. Janszoon decided to terminate his exploration return at a place he named Cape Keerweer ("Turnabout"), south of Albatross Bay. He called the land he had discovered Nieu Zelant (New Zealand), a name that was not adopted. Janszoon made a second voyage to Australia in July 1618. He had landed on an island southeast of the Sunda Strait, which is presumed to be the peninsula from Point Cloates on the Western Australian coast.

Abel Tasman, the Discoverer of New Zealand and Tasmania

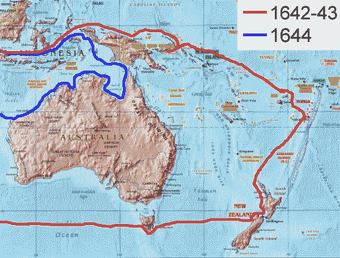

In 1642, Dutchman Abel Janssen Tasman (1603-1659) discovered the Tasman Sea and Tasmania, which were both named after him, and then New Zealand. Tasman was sent by the Dutch East Company from Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies to find if New Guinea was attached to Australia. He instead found New Zealand, Tasmania and the Fiji Island. On his second voyage Tasman circumnavigated Australia at some distance (Matthew Flinders is considered the first man to properly circumnavigate Australia, in 1801-18030.

In August 1642, Tasman left Mauritius, near Africa, missed Australia, found Tasmania in November 1642, continued east and found New Zealand in December 1642 , missed the strait between the north and south islands, turned northwest, missed Australia again and sailed along the north coast of New Guinea. In 1644, he followed the south coast of New Guinea, missed the Torres Strait, turned south and mapped the north coast of Australia.

Tasman wrote he hoped to discover the "remaining unknown part of their terrestrial globe" which "comprise well-populated districts in favorable climates and under propitious skies" and so "in the eventual discovery of so a large a portion of the world...be rewarded with certain fruits of material profit and immortal fame."

On his second voyage in 1644, Tasman also contributed significantly to the mapping of Australia proper, making observations on the land and people of the north coast below New Guinea. Tasman named Tasmania Van Diemen's Land (the island wasn't renamed Tasmania until 1856). His voyage was considered a failure because no ways of making money were discovered.

Despite Janszoon’s achievement Captain Cook is often credited with being the man who discovered Australia. April Holloway wrote in Ancient Origins: Every child in Australia learns about the ‘heroic efforts’ of Captain James Cook, the British explorer, navigator and captain who is credited with leading the way to British colonisation of the country, and who in many cases, is also credited with being the first foreigner to discover the land. However, ask any Australian who Willem Janszoon is, and they will most likely respond with a blank look. In fact, he was a Dutch navigator who reached Australia 164 years before James Cook. But this is not taught in Australian schools. [Source: By April Holloway, Ancient Origins, May 24, 2014]

FIRST EUROPEAN IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Were the Portuguese the First European to Land on Australia

In the late 2000s, Christopher Doukas, a teenage boy, came across an old swivel gun in Darwin, Australia. Analysis of the metal used to make the canon linked the cannon’s lead to a mine in Spain, which some say suggested that the Portuguese reached Australia before the Dutch made the first European sighting of Australia in 1606.[Source: By April Holloway, Ancient Origins, May 24, 2014]

April Holloway wrote in Ancient Origins: A study conducted by the University of Melbourne has shown the lead in the 16th century cannon most closely resembled metal found at the ancient Coto Laizquez mine in the Andalusia region in Spain's south. The historians compared lead in the cannon to ore samples obtained from 2000 European sources and ruled out the theory that the gun was a later Asian copy of the Portuguese swivel. A Darwin-based heritage group, Past Masters, said that the findings showed the lead in the gun was mined on the Spanish Iberian Peninsula. 'This truly is the smoking gun of the Portuguese discovery of northern Australia,' a spokesman for the group, Mike Owens, told The Times .

The cannon isn't the first finding that has suggested Australia might need to rewrite its history books. The discovery of Ancient African kingdom Kilwa coins in the Northern Territory, believed to date from about 1100, have long posed questions about foreign visits to far off Australian shores. In addition, the 2013 finding of a mysterious skull of a European male in New South Wales dating back to the 1600s, disappeared from the Australian news, just as quickly as it appeared.

Fighting over dates and who was the very first to discover the lands seems rather inconsequential when you consider that the Australia Aborigines inhabited Australia for at least 50,000 years before Cook’s arrival. But there is a bigger issue at stake here than just ‘who was the first?’. The point is that early discoveries of Australia were quietly scratched out of the school syllabus and many history books, as giving credit to the ‘colonisers’ was far more important. Similarly, new discoveries providing evidence of early foreign visits are quickly rejected or swept under the carpet. And this is a common pattern. We know for example, that Christopher Columbus was also not the first foreigner to step foot in the Americas.

Early British Explorers in Australia

William Dampier, an English pirate, landed on the west coast of Australia in 1688 when he beached a ship on the northwest coast. The eastern shore wasn't charted until 1770 when Captain James Cook explored the region. In 1699, Dampier was sent to find the east coast of Australia. He sailed along the west coast, went north to Timor, followed the north coast of New Guinea to the Bismarck Archipelago and abandoned his search because his ship had become rotten. Until Captain Cook arrived in January 1770 the east coast was completely unknown and New Zealand had only been seen once.

Rival French and British expeditions set out for the unknown coast of Australia at roughly the same time. The British moved faster. The French were slowed, as one French sailor complained because the captain was more intent “to discover a new mollusk than a new landmass.” The two expeditions met up in what is now Encounter Bay, on the south coast of Australia, in 1702, a French officer told the British captain: “If we had not been kept so long picking up shells and catching butterflies...you would not have discovered the south coast before us.’ The French returned home with their prized specimens as the British took moves to colonize what became Australia.

Lapérouse and Early French Explorers in Australia

The French landed at Shark's Bay in 1772, claimed Australia for France. They buried a bottle containing parchment and coins, left and forgot about it. The French explorer Jean-Frabçois Comte de Lapérouse just missed claiming Australia for France. He arrived in an area near Sydney now called Lapérouse in 1788. Born into a noble family, he strongly desired to go to sea as a child and joined the French navy when he was 18. He participated in the American War of Independent. In 1785 he sailed in waters north of Japan, the first European to do so. He was known as a cautious and bold” navigator and he didn’t retaliate against local people if they killed one of his men.

The news of Cook’s voyages in Australia alarmed Paris in the midst of the French Revolution. Worried about British claims in the Pacific, French King Louis XVI decided to dispatch two ships the Astrolabe and the Boussole to the Pacific. Under the command of Lapérouse. The ships sailed around South America and entered the Pacific Ocean, making their way to Hawaii, Manila and waters around Japan before arriving in Botany Bay near Sydney. They spent about six weeks there. The ships then left for New Caledonia and the west coast of Australia and were never heard from again. Jules Verne later wrote about the extraordinary interest in Lapérouse.

Lapérouse (Laperouse, La Perouse, la Pérouse) was appointed by King Louis XVI to lead an expedition around the world, specifically to explore the north and south Pacific, the Far East and Australia. The mission was to try to augment Cook’s surveys and discoveries and to establish trading contacts. Lapérouse’s captained the ships the Astrolabe (under Fleuriot de Langle) and the Boussole. The two frigates had a crew made up of 225 officers, sailors and scientists. The voyages of Lapérouse took place world in the years 1785, 1786, 1787 and 1788.

Lapérouse departed the French port of Brest in 1785. The range of places he visited was impressive to say the least — Chile, Hawaii (he was the first European on the island of Maui, the second largest of the Hawaiian Islands), Alaska, California, East Asia, Japan, Russia, and the South Pacific. He arrived off Botany Bay in January 1788. From there he was able to send back to Europe his journals, charts and letters on board the Royal Navy ship the Sirius (a report about the expedition had been sent back earlier by M. de Lesseps, who left the group at Kamchatka, Russia).

Mysterious Disappearance of Lapérouse

Lapérouse and his crew vanished. They are believed to have died on the island of Vanikoro, one of the Santa Cruz Islands and part of the Solomon Islands in the south Pacific, where remains of the French ships were discovered in the 1820s. A recent expedition recovered artefacts from the wrecks. Dr Garrick Hitchcock, of the Australia National University School of Culture, History and Language, believes the last survivors of La Pérouse’s voyage were shipwrecked on the Great Barrier Reef near Murray Island, in northeast Torres Strait.

According to Australia National University: What is known is that La Pérouse’s ships Astrolabe and Boussole were wrecked in 1788 on Vanikoro, a small island in the Santa Cruz Group of the Solomon Islands. The survivors made it to shore and spent several months constructing a small two-masted craft, using timber salvaged from the wreck of the Astrolabe. Once completed, they launched the vessel in a bid to return to France. What became of this ship and its crew, desperate to return to France, has been an ongoing mystery.” While researching a project on the history of Torres Strait, Dr Hitchcock came across an article published in an 1818 Indian newspaper, The Madras Courier. He is confident the article reveals what became of the survivors. [Source: Australia National University, August 31, 2017]

The article tells the story of Shaik Jumaul, a castaway Indian seaman who survived the sinking of the merchant ship Morning Star which was wrecked off the coast of north Queensland in 1814. Jumaul made it to Murray Island, where he lived for four years, learning the language and culture of the Islanders. He was finally rescued by two merchant ships that passed through the area in 1818.

“Jumaul informed his rescuers that he had seen cutlasses and muskets on the islands which he recognised as not being of English make, as well as a compass and a gold watch,” he said. “When he asked the Islanders where they obtained these things, they related how approximately thirty years earlier, a ship had been wrecked on the Great Barrier Reef to the east, in sight of the island. Boats with crew had come ashore, but in the fighting that followed, all were eventually killed, except a boy, who was saved and brought up as one of their own, later marrying a local woman.”

The La Pérouse expedition crew list includes a ship’s boy (mousse), François Mordelle, from the port town of Tréguier in Brittany, northwestern France. Dr Hitchcock wonders if Mordelle could be the last survivor of the La Pérouse expedition. “The Indian newspaper article featuring the castaway’s account was later reproduced in several other newspapers and periodicals of the day, in Australia, Britain, France and other countries, and observers noted that this might refer to the La Pérouse expedition,” Dr Hitchcock said. “Somehow, Shaik Jamaul’s story was subsequently largely forgotten.”

While a French book published in 2012 refers briefly to this newspaper article and discounts it as unreliable account, Dr Hitchcock believes otherwise. “The chronology is spot on, for it was thirty years earlier, in late 1788 or early 1789, that the La Pérouse survivors left Vanikoro in their small vessel,” he said. “Furthermore, historians and maritime archaeologists are not aware of any other European ship being in that region at that time. This means that this is the earliest known shipwreck in Torres Strait, and indeed, eastern Australia” he said. “It could well be that the final phase of the La Pérouse expedition ended in tragedy in northern Australia. Future recovery of artefacts from the wreck site on the Great Barrier Reef — yet to be discovered — or the islands, will hopefully provide final confirmation.” The Torres Strait region, which includes the northern part of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, is studded with reefs, rocks and sandbars, and has been described as a ‘graveyard of ships’. Over 120 vessels are known to have come to grief in its treacherous waters.

Captain Cook

The period of serious European exploration of Australia and settlement began on August 23, 1770, when Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy took possession of the eastern coast of Australia in the name of George III. His party had spent four months in exploration along eastern Australia, from south to north. Unlike Dutch explorers, who deemed the land of doubtful value and preferred to focus on the rich Indies to the north, Cook and Joseph Banks of the Royal Society, who accompanied Cook for scientific observations, reported that the land was more fertile. Cook’s fame in Britain helped to fix the attention of the British government on the area, which had some strategic significance in the European wars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2005]

Captain James Cook made three major voyages in the Pacific

First voyage (1768–1771)

Second voyage (1772–1775)

Third voyage (1776–1779)

Cook and his crew recorded in great detail the people of the areas that they visited — their appearance, dress, language, customs, beliefs and activities.

In these voyages, Cook sailed thousands of miles across largely uncharted areas of the globe. He mapped lands from New Zealand to Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean in greater detail and on a scale not previously charted by Western explorers. He surveyed and named features, and recorded islands and coastlines on European maps for the first time. He displayed a combination of seamanship, superior surveying and cartographic skills, physical courage, and an ability to lead men in adverse conditions.

Related Articles: CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Early Maps of Australia

Maps that showed Terra Australis (See Above) include possibly a Fragment of the Piri Reis map by Piri Reis in 1513; the Western hemisphere of the Johannes Schöner globe from 1520; and Oronce Fine double cordiform (heart-shaped) map of the world from 1531. On the Gerard de Jode, Universi Orbis seu Terreni Globi, 1578, is a copy on one sheet of Abraham Ortelius' eight-sheet Typus Orbis Terrarum, from 1564, Terra Australis is shown extending northward as far as New Guinea. [Source: Wikipedia]

The map of Melchisédech Thévenot (1620–1692) of New Holland (Australia) of 1664 is, based on a map by the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu. This is a typical map from the Golden Age of Dutch cartography. It includes Nova Guinea (New Guinea), Nova Hollandia (mainland Australia), Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), and Nova Zeelandia (New Zealand).

A map of the world inlaid into the floor of the Burgerzaal ("Burger's Hall") of the new Amsterdam Stadhuis ("Town Hall") in 1655 revealed the extent of Dutch charts of much of Australia's coast. Based on the 1648 map by Joan Blaeu, Nova et Accuratissima Terrarum Orbis Tabula, it incorporated Tasman's discoveries. In 1664 the French geographer Melchisédech Thévenot published a map of New Holland in Relations de Divers Voyages Curieux. Thévenot divided the continent in two, between Nova Hollandia to the west and Terre Australe to the east. Emanuel Bowen reproduced Thevenot's map in his Complete System of Geography (London, 1747).

Image Sources:

Text Sources: Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2025