Home | Category: History and Religion / Maori / Government, Economics and Agriculture

TRADITIONAL MĀORI GOVERNMENT

Māori society has traditionally been organized into a hierarchy of theocratic chiefdoms that closely approximate a state. Under the divine authority of the gods, chiefs have traditionally directed large feasts, arranged sacrifices, and organized the construction of buildings with taxes and labor conscripted from the people.

In traditional Māori villages, individuals live primarily within “whanau” (extended families) which are combined into groupings called “hapu” (clans). The largest groups are called “iwi” (tribes), which are headed by “rangatira” (chiefs). An important chief is said to have great “mana” and is seen as “tapu”. Many tribes have similar but different myths and gods. Iwi whose ancestors arrived in New Zealand in the same canoe were considered to constitute a waka, which literally means "canoe." A waka was essentially a confederation whose members felt obligated to help one another.

The rangatira of the most senior hapu was the paramount chief (ariki) of the tribe. Therefore, the tribe was the most politically integrated unit in Māori society. Chieftainships were passed on patrilineally (based on descent through the male line) to the first son in each generation. In some tribes, a senior daughter was also given special recognition. [Source: Christopher Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Chiefs were of high rank and were usually quite wealthy. Although they exercised great influence, they lacked coercive power. They organized and directed economic projects, led marae ceremonies, administered their group's property, and managed relations with other groups. Often, the chiefs were fully trained priests with ritual responsibilities and powers, most importantly the right to impose tapu. The rangatira and ariki were very tapu and had much mana. Household heads, or kaumatua, constituted the community council (runanga), which advised and influenced the chief. |~|

RELATED ARTICLES:

MĀORI KINGS AND QUEENS: KINGITANGA, LIVES, REIGNS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN THE PACIFIC REGION, POLYNESIA AND MELANESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

WAKA (MĀORI CANOES): HISTORY, TYPES, ART, HOW THEY ARE MADE ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Traditional Māori Law

At the time of the Treaty of Waitangi’s signing in 1840, Māori society operated under a sophisticated system of customary law. These laws were grounded in core cultural concepts such as: 1) Mana — authority, prestige, or status, either inherited or earned through achievement. 2) Tapu — sacred restrictions or prohibitions governing people, places, and actions. 3) Rāhui — a form of tapu used to restrict access to certain areas or resources, often for conservation or mourning. 4) Utu — the principle of reciprocity or balance, involving repayment for another’s actions, whether hostile or generous. 5) Muru — a ritual form of utu, involving the ceremonial seizure of property to compensate for an offence or wrongdoing. [Source: Te Ara — The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

When British officials began introducing colonial law to New Zealand, they recognised that Māori already had an established system of justice. Some early legislation therefore attempted to incorporate customary practices: The Native Exemption Ordinance 1844 and the Resident Magistrates’ Act 1867 allowed Māori convicted of theft to pay compensation to the victim — a practice similar to muru. The Resident Magistrates Courts Ordinance 1846 required that disputes involving only Māori be heard by a resident magistrate with two Māori chiefs assisting. The chiefs typically determined the verdict, ensuring Māori perspectives shaped the outcome.

Colonial administrators viewed the inclusion of Māori custom in early law as temporary, assuming Māori would eventually assimilate into European society. Over time, all early laws acknowledging Māori custom were repealed or replaced, creating a single legal system that applied equally to Māori and non-Māori — but one based on British principles. Some later legislation actively suppressed traditional Māori practices. The Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 made it illegal to practise as a tohunga (spiritual expert or healer). Although this law was rarely enforced, it reflected official disapproval of Māori spiritual and healing traditions.

By the 1970s, a new wave of Māori activism brought renewed attention to historical injustices and the erosion of Māori law and rights. Events such as the Māori Land March (1975), and the occupations of Bastion Point and the Raglan golf course (1978), highlighted widespread discontent and called for recognition of Māori sovereignty and custom.

Māori Electorates and Parliament

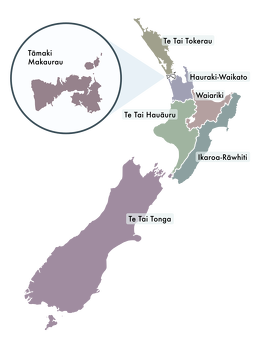

In New Zealand’s government, Māori electorates — commonly known as the Māori seats — are a unique category of parliamentary electorates reserved for representatives of Māori in the New Zealand Parliament. Every part of New Zealand falls within both a general electorate and a Māori electorate. As of 2020, there are seven Māori electorates. While candidates for these electorates have not been required to be Māori since 1967, only those who declare Māori descent may register to vote in them. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Māori electorates were first established under the Māori Representation Act of 1867, designed to ensure Māori had a direct voice in Parliament. The first elections for these seats took place the following year during the 4th New Zealand Parliament. Originally intended as a temporary five-year measure, the electorates were extended in 1872 and made permanent in 1876. Despite repeated efforts to abolish them, the Māori seats remain a distinctive feature of New Zealand’s political system.

In practice, Māori electorates function similarly to general electorates, with the key difference being that voters of Māori descent may choose to enrol on the Māori roll instead of the general roll. Two aspects distinguish Māori electorates from their general counterparts. First, successful representation requires particular skills and cultural competencies—such as fluency in te reo Māori, knowledge of tikanga Māori (customs), strong whakawhanaungatanga (relationship-building) abilities, and confidence in marae settings—to maintain accountability to Māori communities. Second, Māori electorates are much larger geographically, with each typically encompassing the area of five to eighteen general electorates.

The Kauhanganui is sometimes called the Māori Parliament but it isn't really. Kauhanganui(or Te Kauhanganui) is a historical term for the Māori parliament established by the Māori King Movement (Kingitanga) and a modern term for the governing body of the Waikato-Tainui iwi. Historically, it was a meeting and discussion place for Māori leaders to deal with issues like land problems and to negotiate with the colonial government. Today, Waikato-Tainui's governing body, now known as Te Whakakitenga o Waikato, has the name "Te Kauhanganui" in its structure.

Te Pati Māori — Māori Political Party

Te Pāti Māori (the Māori Party) is a political party in New Zealand that advocates for the rights and interests of Māori, the country’s Indigenous people. The party primarily contests the Māori electorates—seats reserved for Māori representation in Parliament—where its main political rival is the centre-left Labour Party. Under the current co-leadership of Rawiri Waititi and Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, Te Pāti Māori promotes policies centred on upholding tikanga Māori (Māori customs and values), dismantling systemic racism, and strengthening the rights and tino rangatiratanga (self-determination) guaranteed under Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi). The party’s political stance is generally described as centrist to centre-left. [Source: Wikipedia]

Te Pāti Māori was founded in 2004 by Tariana Turia, who resigned from the governing Labour Party, where she had served as a minister, in protest over the foreshore and seabed ownership controversy. She was joined by Pita Sharples, a respected academic and community leader, and together they became the party’s first co-leaders.

The Māori Party made a strong debut in the 2005 general election, winning four Māori seats and entering Parliament as part of the Opposition. In subsequent elections—2008, 2011, and 2014—it won five, three, and two Māori seats respectively, and during this period supported a centre-right National Party-led government. Although Te Pāti Māori remained independent, its co-leaders held ministerial roles outside Cabinet, enabling the party to advance Māori-focused initiatives within government.

The party lost all its seats in the 2017 election, but made a comeback in 2020 when Rawiri Waititi won the Waiariki electorate. Despite receiving only 1.17 percent of the nationwide party vote (slightly less than its 2017 share), winning an electorate seat entitled the party to proportional representation, resulting in two MPs entering Parliament—Waititi and Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, who became a list MP. As of 2021, both serve as co-leaders and sole representatives of Te Pāti Māori in Parliament.

Traditional Māori Land Claims

In traditional Māori society, rights to land and its resources were held collectively by iwi (tribes) or hapū (sub-tribes). Individual rights were derived from membership within these groups. Such rights were maintained through continuous occupation or use — which might include living permanently on the land, visiting seasonally, or establishing temporary camps for hunting, fishing, or gathering. The principle of ongoing occupation was expressed through the concept of ahi kā — literally, “keeping the home fires burning.” Maintaining one’s ahi kā demonstrated active connection to the land and affirmed ownership rights. [Source: Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Anthropologist Douglas Sinclair wrote; “If a woman left her fireside to marry outside the tribe it was said that her fire had become an unstable ahi tere. If she or her children returned, then the ancestral fire was regarded as rekindled. By this act the claim had been restored. If the fire was not rekindled by grandchildren, then the claim was considered to have become cold — ahi mataotao.”

In this way, continuous occupation — whether through residence, cultivation, or ritual — kept claims alive. If an area was abandoned for three or more generations, the ancestral connection and the right to the land could be considered extinguished.

An iwi or hapū could assert its claim to land through a recognised take (basis of right), which was then strengthened by occupation (ahi kā). Common forms of take included: 1) Take taunaha or take kite – right by discovery of the land; 2) Take raupatu – right by conquest through warfare; 3) Take tukua – right by gift or formal transfer from another group; 4) Take tīpuna – right by ancestral descent, proven through recitation of whakapapa (genealogy).

Customary markers and evidence were used to establish and remember occupation rights, including: 1) Tūāhu – sacred stone mounds or markers erected at the time of first settlement. 2) Tohu – visible signs of human presence, such as tree carvings, rock markings, or burial sites for umbilical cords (iho) of chiefly children and for the bones of ancestors. 3) Knowledge of resource sites – such as recognised places for eeling, fishing, hunting, and food gathering. 4) Ātete – proof of successful defence of land or resources against challengers. The concept of ahi kā embodied both a spiritual and practical connection to land — linking genealogy, identity, and custodianship through the unbroken continuity of occupation.

Apologies and Compensation to the Māori

In 1975, New Zealand established processes where Māori could seek reparations for the atrocities committed through colonisation. According to Guardian the settlement system was set up remedy the crown’s breaches of the country’s founding document between the British crown and Māori, the Treaty of Waitangi. As of 2022, 97 deeds of settlement have been signed and another 73 have passed into law. There are approximately 40 remaining settlements to go. [Source: Eva Corlett in Wellington, The Guardian, September 23, 2022 ~]

In May 1995, after the Waitangi Tribunal announced that the Māori had been seriously mistreated, the New Zealand Prime Minister signed a document in which the government apologized for wrongs committed by British settlers in wars in the 1860s. Over 45,000 acres of land and cash worth US$120 million was given to the Taunui, one of the largest Māori tribes, as compensation for treaty violations.In addition, the government set up a bicultural system which recognizes the general rights of the Māori while dealing with individual issues raised some of them. Māori is now the second official language of New Zealand along with English and it is being taught more and more in schools and featured on television and radio programs. Even Air New Zealand jets now have Māori names.

One of the most prominent Māori activist Professor Pita Shraples has played a big part in getting Māori culture, history and language incorporated into the New Zealand school curriculum. In 1996, 15 Māori Members of Parliament were elected to the New Zealand Parliament and three Māori were appointed to the 20-member cabinet by Prime Minister Jim Bolger. In the year 2000, the assets of the Māori businesses was worth US$2 billion.

In June 2008, The New Zealand government signed its biggest ever settlement of indigenous Māori grievances, agreeing to hand over nearly NZ$420 million in forestry assets to seven tribes.A collective representing about 100,000 Māori in seven iwi, or tribes, in the central North Island signed the deal under which they will receive 176,000 hectares of commercial forestry land worth more than NZ$195 million. They also received NZ$223 million in accumulated rents as well as yearly rental payments of about NZ$13 million. The deal is part of a process of settling Māori grievances over their loss of land and other natural resources after sovereignty of the country was signed over by many Māori chiefs to Britain in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. [Source: AFP, June 25, 2008]

In 2022, Māori tribes secured a landmark apology and compensation over colonial atrocities — including “indiscriminate” killings of women and children during the Waikato wars and looted and destroyed iwi property. The New Zealand government said the Ngati Maniapoto iwi had suffered for too long from “inadequate healthcare, housing and education, as well as reduced employment opportunities”. The Guardian reported: The gallery erupted into waiata (song) and haka (ceremonial dance) as the House unanimously voted to pass the law. As well as an apology, the Waikato-based iwi of nearly 46,000 members received NZ$177 million in financial redress — New Zealand’s fifth-largest sum of its kind — and the return of 36 sites of cultural significance. ~

Backlash by Whites Against Pro-Māori Policies

In December 2023, New Zealand’s new right-leaning government under Prime Minister Christopher Luxon said it was going to reduce or eliminate pro-Māori policies backed former leader Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern that won fans amongst progressives worldwide. CNN reported: Under Luxon, the government is proposing to dissolve the country’s Māori Health Authority, rollback the use of the Māori language, and end the country’s limits on tobacco sales – a move Māori leaders had sought to cut high rates of smoking among their people. “Your attacks on our culture have motivated our standing in solidarity,” the co-leader of the Te Pati Māori party, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, said. [Source: Angus Watson, CNN, December 18, 2023]

The same day, the Māori King, Tuheitia Potatau Te Wherowhero VII, issued a royal proclamation calling for a “national hui” – a coming together of the country’s indigenous people, to discuss “holding the new coalition government to account.” Many New Zealanders feel the same, with tens of thousands of people turning out across the country for anti-government demonstrations hastily arranged by Ngarewa-Packer’s party.

Ardern resigned as Prime Minister in January, handing the leadership to her deputy Chris Hipkins, who attempted to refocus their Labour Party’s policies on the cost-of-living crisis. But it wasn’t enough to extend Labour’s time in office. While Ardern won fans around the world for her compassionate response to the 2019 Christchurch terror attack, her position on climate change and by championing working mothers in politics, her domestic legacy is far more contested. Before the vote, the leaders of the new conservative coalition government, made up of The National Party, New Zealand First, and ACT New Zealand, had all promised to unwind some of Arden’s legacy.

Right-wing candidates railed against the Labour’s perceived expansion of New Zealand’s long-held principle of co-governance, designed to ensure Māori representation in administrative bodies. And in the lead-up to the vote, some Māori candidates complained of racist abuse.

The election on October 14, 2023 saw a flurry of deal-making as Luxon sought to shore up his thin margin with smaller players. In late November, the new partners published a 100-day plan under which initiatives designed to benefit Māori will be rolled back, including a vow to dissolve the Māori Health Authority established in 2022 with a mandate to improve the health of indigenous people.

The plan also backflips on Ardern’s world-leading ban on the sale of cigarettes to people born after 2008 – also seen as anti-Maori as some 20 percent of Maori adults smoke, far higher than the national average of 8 percent. Organizations such as The Maori Women’s Welfare League, that works to empower Maori women and children, have vowed to hold Luxon accountable on his assertion that Maori health outcomes will be improved by what his government argues will be a reduction in red tape. “They are not things that are dreamed up in five minutes. They are established because of evidence over time,” Maori Women’s Welfare League President Hope Tupara said. “We saw (the Ardern administration) increasing the amount of government investment into Maori health solutions by Maori providers on the basis of ‘by Maori for Maori.’ “We have an expectation of the kinds of public services that are available to us as part of the population, which I think is reasonable.”

Richard Shaw, a professor of politics at New Zealand’s Massey University, described Luxon’s government as “the most explicitly anti-Maori government” he could remember. “This is the first government that I can recall which has quite explicitly said, ‘we’ll have less of that,’ not ‘we’ll have more of it,’” said Shaw.

Luxon’s National Party, which won just over 38 percent of the vote is forced to govern in coalition with the far smaller, and less moderate New Zealand First and ACT New Zealand parties. Both junior coalition parties will drag Luxon to the right. New Zealand First has long opposed the official use of Maori terms, from road signs to government departments. The party says the widespread practice of referring to New Zealand by the country’s Maori name, Aotearoa, is an example of “virtue signalling and politically correct extremism.” Luxon says his government will adopt an “English first” approach.

ACT is forcing Luxon to entertain the possibility of a future referendum on the principles of New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi. While Luxon says the proposed referendum would “go no further” than a debate by a parliamentary select committee, the open questioning of the usefulness of the treaty may diminish it as a historic declaration of equality, warns academic Shaw from Massey University.

In 2024, Politician David Seymour introduced the Treaty Principles Bill, which critics aid aimed to "eliminate dedicated land, government seats, health care initiatives, and cultural preservation efforts granted to the Maori people under the Treaty of Waitangi," per ABC News. During the a vote on the bill, 22-year-old Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke — who is the country's youngest-ever member of Parliament — interrupted the session and led haka and ripped a copy of the bill in half! The video of her display went viral.[Source Morgan Sloss, BuzzFeed, November 19, 2024]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025