Home | Category: History and Religion / Maori

MĀORI RELIGION

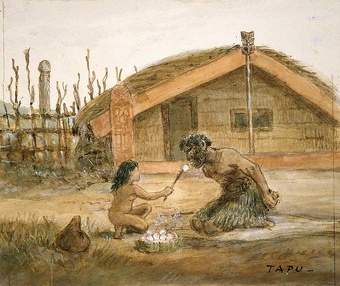

The Māori natural world was filled with gods and spirits that required thoughtful navigation; Tohunga (priests) assisted people with special incantations and rites to appease the gods; Here a child feeds a tohunga food on a stick; The spiritual role of tohunga meant items that were noa (common) such as food could not be touched in case they affected tapu

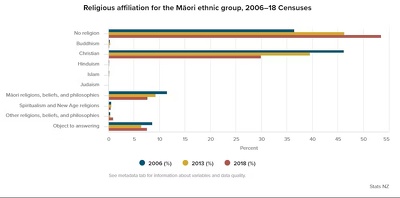

Approximately 29.9 percent of Māori identified as Christian in the 2018 New Zealand census, a significant drop from 46.2 percent in 2006. The percentage of those with "no religion" increased to 53.5 percent in the same time period. The decrease in Christian affiliation is attributed to factors including the colonial history of religion and a broader rejection of traditional religious frameworks.

Missionary work and colonization in New Zealand has influenced religious trends among Māori. New Zealand as a whole has seen a general decline in religious affiliation and an increase in the "no religion" category. The unique Māori church encompasses a large percentage of the Christian Māori although its numbers too have declined. Ringatu is another traditional Māori Christian denomination.

According to a census taken in 1966, 30 percent of all Māori interviewed were members of the Church of England, 18 percent were Catholic, 8 percent were Mormons, 7 percent were Methodist and 15 percent belonged to two Māori sects: Ratana (established in the 1920s) and Ringatu (established in the 1860s by Te Kooti).

Even though many Māori are Christians they still retain elements of their traditional religion. New Zealand writer Margaret Orbell wrote, "Modern western thinking speaks of nature and the natural world in contrast with culture, by which we mean human activities and thought. Māori, alternatively, do not see their existence as something separate or opposed to the world around them. All forms of life, in this context are related."

RELATED ARTICLES:

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN THE PACIFIC REGION, POLYNESIA AND MELANESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI TATTOOS: HISTORY, HOW THEY WERE MADE, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WAKA (MĀORI CANOES): HISTORY, TYPES, ART, HOW THEY ARE MADE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Traditional Māori Religion

The Māori have traditionally believed that natural and supernatural worlds were one, and there was no Māori word for "religion." Missionaries introduced the term "whakapono" to describe religion. Whakapono also means faith and trust. The ancient Māori religion was concerned to some degree with marshalling supernatural forces to help to induce fertility and bring plentiful food supplies. The indigenous Māori religion declined when Europeans introduced Christianity. [Source: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications; Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

The Māori had a spiritual view of the universe. Anything associated with the supernatural was imbued with tapu, a mysterious quality that rendered those things or persons either sacred or unclean, depending on the context. Objects and people could also possess mana, or psychic power. These qualities were inherited or acquired through contact and could be augmented or diminished during one's lifetime. [Source: Christopher Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Most public rites were performed outdoors at the marae. The first fruits of all undertakings were offered to the gods, and slaves were occasionally sacrificed to propitiate them. Incantations (karakia) were chanted in flawless repetition to influence the gods. In the past, with influences still felt today, sickness was believed to be caused by sorcery or the violation of a tapu. The proximate cause of illness was the presence of foreign spirits in the sick body. The medical tohunga accordingly exorcised the spirits and purified the patient. The therapeutic value of some plants was also recognized. [Source: Christopher Latham,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Ancestor worship was an important part of traditional religion and certain attributes were accorded the dead. According to the The Telegraph: In 1864, during a Māori uprising against the British, Captain PWJ Lloyd was killed, and his severed head became the divine conduit for the angel Gabriel, who, among other fulminations, had not one good word to say about the Church of England. [Source: Simon Ings, The Telegraph, January 7, 2022}

Māori Gods

The Māori had a pantheon of supernatural beings (atua) that were at the center of their religion. It has been said they had supreme god named Io, whose name was so sacred worshippers were not even supposed to say it. Even so Io has many names, including Io-matua-kore – Io the parentless one and scholars debate about whether there was a supreme god in Māori tradition. There were (and are) also exclusive tribal gods, mainly associated with war, and various family gods and familiar spirits.

Māori gods are similar to gods found in other Polynesian cultures and different names were used by different groups.. Other important Māori gods include “Tane Mahuta” (God of the Forest), “Tangaroa” (God of the Sea), “Rua Moko” (God of Volcanoes and Earthquakes), “Tawhiti Matea” (God of Wind and Storms), “Papa" (Earth Mother) and “Rangi” (Sky Father). Maui is a demigod who is credited with creating the North Island of New Zealand when he pulled it out of the ocean as a large fish.

The Pleiades constellation is important to the Māori. Its pre-dawn rising in June represents the beginning of the Māori New Year. Māori consider this group of stars to represent a mother and her six daughters. The gods of war were Maru, Uenuku, Kahukura and Tuma Taunga.

Volcanoes and mountains are considered sacred to the Māori. According to one legend all the mountains on New Zealand were once members of tribe that were located together at the center of the North Island. After getting into a ferocious battle over a female mountain they were forced to disperse all across the islands. Most Māori gods are male. Because women’s menstrual cycles coincided with the phases of the moon, they often appealed to the moon god for protection and guidance before childbirth. The Māori have have traditionally looked for a woman in the moon with a bundle of gourds.

Māori Sacred Spaces and Objects

Carved sticks representing the Māori gods Tūmatauenga (god of war), Tāhirimātea (storm god), Tāne (god of forests), Tangaroa (sea god), Rongo (god of cultivated plants and peace), and Haumia (god of wild food plants), from between 1887 and 1891

For the Māori, particular places and objects are tapu, or sacred. These include shrines, containers for gods, waterways designated for religious purposes, and places that are intrinsically tapu or tapu because important events occurred there. A marae is a sacred, communally-owned complex of buildings and grounds that serves as the focal point for Māori communities, representing a "place to stand" and belong (tūrangawaewae). “It has traditionally been the focal point of traditional Māori life. Māori gather there for meetings (hui), celebrations (āhuareka), welcoming ceremonies (pōwhiri), funerals (tangi), and celebrate important events such as weddings, christening and birthdays. It also a place where "challenges" are made, debates and discussions are held, old traditions and legends are kept alive, and youth are taught traditional songs, chants and dances. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

A tūāhu is a simple shrine located away from a kāinga, or village. It consists of a heap of stones. A tūāhu with an enclosed post was called a pouahu. A wooden box containing the tribal god would be kept in the enclosure. Small, carved wooden houses on posts, called kawiu, also contained waka. Sometimes a whata (stage) was erected. A number of rituals required water from a stream or pond. Wai tapu, or sacred waters, were set aside for this purpose. These waters were used to dedicate children to the gods, cleanse people of tapu, and remove tapu from warriors returning from battle.

Some areas were considered tapu, or restricted. These included burial grounds, sites where people had been killed, and trees where children's placentas had been placed. They also included the tops of tribal mountains. Certain prohibitions applied to these areas. People had to either stay away from them or refrain from breaking their tapu. For instance, they could not take food to wāhi tapu. Village latrines were known as turuma or paepae. They were used by tohunga in various rituals, including ngau paepae ("biting the crossbar of the latrine").

Some objects contained atua and were used in ceremonies associated with fertility. Taumata atua (abiding places of the gods) were stone images placed near food crops to protect their vitality. Whakapakoko atua, or god sticks, were usually carved with a pointed end so they could be inserted into the ground. These temporary shrines for the gods were also used to ensure the fertility of crops or the abundance of fisheries.

The ancient Māori made god sticks, featuring the sea god, river god and war god, that were comprised of linen string wrapped around a stick in a distinct crisscross pattern. Unraveling the string was thought to get the gods attention. The patterns found on the sticks were also painted or tattooed onto Māori faces. "World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Māori Creation Myth

Māori accounts of creation typically start with Te Kore (chaos or the void), followed by Te Pō (night), and finally, Te Ao Mārama (the world of light). This process occurred over eons of time. There are numerous stages of Te Kore, Te Pō, and Te Ao Mārama recorded in different genealogies, with each stage giving rise to the next. The order of these stages varies in different tribal retellings. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

In the Māori creation story, the sky was a male god named Rangi and the earth was a goddess called Papa. Depending on where the story is told they beget between six and seventy children who lived between their parents and became gods of natural forces that eventually pushed the sky upward with poles. Rain is considered to be the tears of the sky who misses his loved ones on earth.

According to a popular version of the myth, the two primeval parents, Papa and Rangi, had eight divine offspring: Haumia, the god of uncultivated food; Rongo, the god of peace and agriculture; Ruaumoko, the god of earthquakes; Tawhirimatea, the weather god; Tane, the god of forests and the father of humans; Tangaroa, the sea god; Tu-matauenga, the war god; and Whiro, the god of darkness and evil. [Source: Christopher Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

A popular telling of the story goes like this: Rangi (Ranginui), the Sky Father, and Papa (Papatūānuku), the Earth Mother, were locked in an eternal embrace. Their children, the departmental gods, were trapped between them in eternal darkness. They decided to try to separate their parents. All of the children except Tāwhirimātea tried and failed to separate them. Then Tāne pushed the sky apart from the earth with his legs. Tāwhirimātea became the god of wind; Tāne, the god of forests; Tangaroa, the god of the sea; Rongo, the god of cultivated foods; and Haumia, the god of uncultivated foods. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

According to Māori tradition, all living things are connected through whakapapa (genealogy). Tāne, the god of the forest, shaped the first woman, Hineahuone, from the soil and took her as his wife. Together, they became the ancestors of humankind. In another tradition, it is Tiki, rather than Tāne, who is regarded as the ancestor of human beings. Whakapapa link people, birds, fish, trees, and natural phenomena, showing how all forms of life are related.

Tohunga — Māori Shaman Priests

Māori priests are known as tohunga. Māori scholar Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Buck) suggested that the term derives from tohu, meaning “to guide” or “to direct.” Ngāpuhi elder Rev. Māori Marsden offered an alternative interpretation, proposing that tohunga comes from another sense of tohu meaning “sign” or “manifestation,” and thus refers to a person who is “chosen” or “appointed.” The term tohunga was also used more broadly to describe experts in particular fields. For example, a specialist in tattooing (tā moko) was called a tohunga tā moko; an expert in carving (whakairo) was a tohunga whakairo; and a priest, whose work involved sacred ritual, was known as a tohunga ahurewa (priest of the sacred place). [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Traditionally, senior deities had a priesthood, the Tohunga Ahurewa, whose members received special professional training. They were responsible for all esoteric rituals, knew genealogies and tribal history, and were believed to control the weather. Rather than priests, shamans served the family gods, communicating with them through spirit possession and sorcery.

Each traditional Māori village had a chief and a priest. The latter possessed “mana” (See Below) and controlled the mana of the tribe. He was often considered to be more important than the chief and is called in to perform magic, dispel witchcraft, heal the sick and communicate with the gods by whistling. Some tohunga were considered so tapu (sacred) that they were unable to feed themselves. Food would be placed on a stick and lifted to their mouths, and water was tipped in from a container. In some cases, a specially made funnel known as a kōrere was used to pour water into their mouths. Tohunga of great tapu were also forbidden from having their hair cut. [Source: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Atua (gods) and spirits communicated through tohunga, who acted as their mediums. When possessed by a spirit, the tohunga would speak in a different voice, regarded as the voice of the god. One well-known example was Uhia, a tohunga of Ngāi Tūhoe, who became a medium for a spirit named Hope-motu, whom he renamed Te Rehu-o-Tainui. A person through whom a god spoke was called a waka atua (vessel of a god) or kauwaka (medium).

A matakite was someone who could perceive events in the future or sense occurrences happening elsewhere. Many tohunga possessed this gift of foresight. In one account, a war party was marching into battle when the god Maru appeared to their tohunga and revealed where the engagement should take place. Following his guidance, the group—though outnumbered—defeated their enemies. In a story from the mid-1840s, a tohunga accompanied a party who had been spear-fishing at Rua-papaka Island in Northland. Upon landing, the tohunga announced that a young girl named Ngā-ripene had died, saying her spirit had passed the bow of their canoe and told him. The others doubted him, as she had been healthy when they last saw her—but on their return, they found his vision to be true.

It was the duty of tohunga to ensure that tikanga (customs and correct practices) were properly observed. They guided their communities and offered protection from spiritual forces. Tohunga were healers of both physical and spiritual ailments, and they performed the rituals associated with horticulture, fishing, bird-snaring, and warfare. They also conducted ceremonies to remove tapu from newly built houses and waka (canoes), and to place or lift tapu in death rituals. In some ceremonies, ruahine (elderly women) and puhi (young virgins) also took part in the removal of tapu from canoes and buildings.

Tipua (Spirits), Taniwha and Road Construction

Supernatural beings are known as tipua. Lesser gods were also referred to as tipua, and travellers would sometimes leave small offerings of branches or twigs to appease them when passing through places they were believed to inhabit. Certain trees and rocks were thought to embody supernatural entities and were likewise called tipua. These rākau tipua (supernatural trees) and kōhatu tipua (supernatural rocks) were often honoured with offerings left nearby by those who passed. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Taniwha are powerful tipua that live in deep water, caves, or forests, and can be either benevolent guardians or dangerous monsters that can take forms such as dragons, serpents, giant lizards, sharks, whales, or even logs. Some taniwha are said to have the ability to change their shape, allowing them to move between different forms. Some taniwha are benevolent and act as guardians for their tribes, guiding and protecting canoes and people. Other taniwha are depicted as terrifying, predatory beings that can eat people, kidnap women, or cause destruction. In the Māori worldview, taniwha were considered part of the natural environment, and the reasons for their presence were often rooted in real-world dangers of the landscape.

In 2002, construction work on a major New Zealand highway has been delayed following warnings about a taniwha in the area. The BBC reported: The Waikato expressway is a 12-kilometer (7.5-mile) stretch of new highway over swamp land in New Zealand's central North Island. According to the local Ngati Ngaho tribe, the region is home to a number of taniwha. Some say the presence of a taniwha might also explain the large number of fatal car accidents along the existing road. [Source: Greg Ward, BBC, November 4, 2002]

Māori concerns about taniwha are treated quite seriously by New Zealand road building agency Transit New Zealand. Transit spokesman Chris Allen says the highway agency will meet tribal elders later this week to confirm whether the highway is encroaching on sacred land. Mr Allen says Transit has specific protocols reflecting the beliefs of local Māori. Reports of a taniwha are regarded as as serious as the discovery of human remains. The company had already been advised of two other taniwha living near the construction route. However in both cases the taniwha were considered by Māori to be a satisfactory distance from the new highway.

Māori concerns about spiritual issues are becoming increasingly common in New Zealand, where Māori culture is enjoying a renaissance. In the far north of the country, members of the Ngapuhi tribe have been involved in a three-year court battle aimed at blocking a new prison, because tribal members claim the planned site is also the home of a sacred taniwha.

Māori Tapu and Mana

The concept of “tapu” (sacredness) is of great significance to the Māori. Tapu can be both good and bad because there is no opposition between good and evil in the Māori religion, and any object can become tapu if it comes in contact with supernatural forces. All men are thought to have tapu in them unless they are captives or slaves, and dead people are regarded as having more tapu than living people. The degree to which people possess tapu is directly proportional to their rank. A person’s tapu is inherited from their parents, ancestors, and ultimately from the gods.

Tapu also extends beyond people to the natural and material world—trees, animals, places, and objects could all possess tapu, influencing how they were approached or used. When something was tapu, behaviour toward it was often restricted to maintain spiritual balance and respect. Some objects or resource regarded as tapu are off-limits. “Marae” (sacred meeting areas) are believed to possess strong tapu. The opposite state is noa, meaning ordinary, common, or free from restriction. Ceremonies were often performed to lift or neutralise tapu, returning people or objects to a noa state so that they could be handled or used without spiritual danger. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Māori believe there is a finite amount of “tapu” and touching a person with “tapu” takes their tapu away. Anyone who offends tapu or touches a person with a lot of tapu risks punishment from the gods. In some cases, offenses against tapu have resulted in death. The tapu of some priests is considered to be so strong that anything they touch becomes tapu and even their shadows are to be avoided. During special rituals in which priests light fires to attract deities, the high priests keep their hands behind their backs and are fed with sticks by specially appointed servants so the priests will remain untouched. For similar reason, water is sometimes also poured in the mouth of high status males.

A person with “tapu” also has “mana” (spiritual authority), which is a power that can control fate as well as a spiritual link between ancestors and living people. Māori believe that successful people have “mana” and when they have setbacks it is because their “tapu” had been disturbed.

Mana describes an extraordinary power, essence, or presence. It encompasses authority, influence, and prestige, and is considered a sacred force that flows from the atua (gods). Mana is greatest among rangatira (chiefs), especially ariki (first-born of chiefly lines), and among tohunga (experts or priests). The concept of mana is closely linked with tapu, as both express the sacred dimension of status and spiritual power. (Source: Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

Mana is an impersonal force that individuals can inherit or acquire in the course of their lives. Tapu refers to a sacredness ascribed by birthright. The two were directly related: chiefs with the most mana were also the most tapu. The punishment for violating a tapu restriction was automatic and usually came in the form of sickness or death.The English word "taboo" derives from this general Polynesian word and concept. [Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999]

Māori Ideas About the Soul, Essence and Life Forces

Mauri is the life principle or vital spark that exists within all living things and objects. It is the essence that binds the physical and spiritual worlds together, giving life and cohesion. People sometimes placed physical objects in forests or fishing grounds to serve as mauri talismans, which embodied and protected the life force of those places. A person whose mauri became weakened was believed to lose vitality, and ultimately, life itself. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

The Hau of a person, living creature, or place is its vital essence or power. Like mauri, hau represents the life force that sustains being, but it also embodies the concept of reciprocity and the spiritual flow between people and the environment. A mauri talisman could be used to safeguard the hau of a person or locality. A forest with its mauri intact was thought to yield abundant birds and fish, for its hau remained strong. In one tradition, when the demigod Māui fished up the North Island, he instructed his brothers not to cut up their catch until he had taken its hau—its sacred essence—to a tohunga, so that the proper rituals could be performed to make it noa (free from tapu).

Wairua is the spirit or soul of a person. It can leave the body and travel, and after death it continues to exist. According to traditional belief, the wairua journeys to raro-henga (the underworld). In northern traditions, this passage follows te ara wairua (the pathway of spirits) to te rerenga wairua (the leaping place of spirits) at the northern tip of Aotearoa, from where the wairua descends into the sea to return to its ancestral homeland.

Ratana

Ratana (Māori: Te Haahi Ratana) is a Māori Christian church and religious movement based at Ratana Pa near Whanganui, New Zealand. The movement began in 1918, when Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana claimed to have received divine visions and began a mission focused on faith healing. The Ratana Church was formally established in 1925, and its followers are known as morehu, meaning “the remnants.” In the 2001 census, 48,975 New Zealanders identified with the Ratana Church, while the 2018 census recorded 43,821 adherents. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ratana initially conducted healings from his family farm and did not intend to found a separate church, encouraging followers to remain within their existing denominations. Christian leaders responded in different ways—some objected to him being called Te Mangai, or “the mouthpiece of God,” while others approved of his rejection of traditional Māori religion and tohunga practices.

The church’s spiritual foundation is based on the Trinity—the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit—augmented by the inclusion of Nga Anahera Pono (“the Holy and Faithful Angels”) and Te Mangai (“God’s Word and Wisdom”) in prayers. Alongside the Bible, services draw on the “Blue Book,” a collection of hymns and prayers written by Ratana himself. From its inception, the church has combined spiritual and political aims and continues to host political leaders annually at Ratana Pa to commemorate Ratana’s birthday.

The main symbol (tohu) of the church is the whetū marama (“shining star”), a five-pointed star and crescent moon that appears on church buildings and is worn by followers. The crescent moon, in gold or blue, represents enlightenment, while the star’s colours each signify an aspect of divine presence: blue for Te Matua (The Father), white for Te Tama (The Son), red for Te Wairua Tapu (The Holy Spirit), purple for Nga Anahera Pono (The Faithful Angels), and gold or yellow for Te Mangai (The Mouthpiece of God, or Ture Wairua). In some cases, pink replaces gold to represent Piri Wiri Tua (The Campaigner in Political Matters, or Ture Tangata). Together, Te Whetū Marama symbolizes the kingdom of light (Maramatanga), standing steadfast against the forces of darkness (makutu).

Ringatu

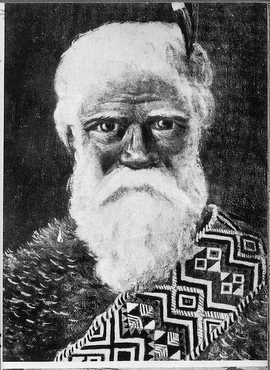

Portrait of Te Kooti, from 1889 or 1891

The Ringatū Church is a Maori Christian denomination in New Zealand, founded in 1868 by Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki—commonly known simply as Te Kooti. Its name and symbol, ringa tū (“upraised hand”), reflect a gesture of faith and prayer central to its identity. Ringatū services are typically held in tribal meeting houses (wharenui), and leadership is shared between the Poutikanga and a tohunga, an expert in church law and ritual. Members of the faith place strong emphasis on memorizing scripture, hymns, and chants. According to the 2006 New Zealand census, about 16,000 people identified as Ringatū, with roughly a third living in the Bay of Plenty. After a thirty-year vacancy, Wirangi Pera was appointed Amorangi (spiritual leader) in 2014. [Source: Wikipedia]

Te Kooti’s early life was turbulent. Known for his rebellious temperament, he was once nearly buried alive by his father and later led a band of lawless companions who raided settlements along the East Coast. After being expelled by his hapu, he became a successful trader sailing between Gisborne and Auckland. When his people joined the Pai Marire (“Hauhau”) movement, Te Kooti initially sided with government forces but was accused of supplying gunpowder to the Hauhau and arrested under martial law. He was exiled to the Chatham Islands with other prisoners during the conflicts of the 1860s.

While imprisoned, Te Kooti experienced a spiritual transformation. Immersing himself in the Bible—particularly the Old Testament—he blended its teachings with Maori cosmology and ritual. He began conducting services, incorporating dramatic performances that drew on both biblical symbolism and traditional Maori spirituality. Using phosphorus to make his fingers glow, he performed visionary displays and took on the form of a ngarara (lizard), a creature of great tapu significance, while speaking in tongues.

His teachings were delivered orally and often framed as riddles or challenges. One famous test involved a white stone, which his followers ground into powder and ate, symbolizing their acceptance of divine wisdom. Te Kooti taught that white quartz stones represented the Lamb of God and incorporated them into Ringatū symbolism. He also declared that the Archangel Michael had commanded him to lead his people against the colonial government—whom he equated with Satan. Drawing parallels between the biblical Israelites’ exile and the Maori loss of land, he positioned himself as a prophet leading his people toward deliverance. His charisma and scriptural knowledge persuaded many prisoners to abandon the Pai Marire faith and embrace his new religion.

In 1868, Te Kooti and his followers seized a ship, escaped from the Chatham Islands, and returned to the North Island. Declaring himself “King of the Maori,” he initiated what became known as Te Kooti’s War, a four-year campaign against colonial forces marked by cycles of revenge (utu) and violent retribution. Though many atrocities occurred, there is no evidence that Te Kooti himself directly participated in acts of torture or murder. His reported ability to elude capture—sometimes attributed to the supernatural powers of his horse—became part of Ringatū legend.

As the conflict dragged on, Te Kooti’s following dwindled under relentless pursuit by Major Gilbert Mair and his largely Maori forces. Eventually seeking refuge in the King Country, Te Kooti was granted sanctuary by the Maori King, Tawhiao, though tensions arose over Te Kooti’s unorthodox behavior, including his drinking, polygamy, and defiance of the King’s authority. Their strained relationship reflected a deeper division between Te Kooti’s prophetic, visionary style and the King Movement’s conservative discipline.

In 1926, the Ringatū Church adopted an official seal designed by Robert (Rapata) Biddle, a minister and secretary of the faith. The crest features the Old and New Testaments encircled by the phrase Te Ture a te Atua me te Whakapono o Ihu (“The Law of God and the Faith of Jesus”). Two upraised hands flank the central emblem, with an eagle perched above—symbolizing God as described in Deuteronomy 32:11–12, protecting His people as an eagle guards its young.

Māori Funerals

In Māori tradition, when a person dies, their wairua (spirit) leaves their body and journeys to Te Rerenga Wairua, the sacred departing place of spirits at the northernmost tip of New Zealand. Their whānau (family) gathers for a tangihanga (funeral ceremony), where they are supported by the wider community in mourning and remembrance. Māori Christian funerals often retain Māori beliefs and sometimes Christian ministers are called in to remove “tapu”. [Sources: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File; Christopher Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Tangihanga are usually held on the marae most closely connected to the deceased. Over several days, mourners remain with the tūpāpaku (body) and the bereaved family, sharing stories, performing rituals, and expressing grief. The event draws people from near and far — sometimes from across the country or overseas — to pay their respects and uphold their obligations to the whānau pani (bereaved relatives). Many of the customs observed during a tangi serve to honour the departing spirit and to comfort those left behind.

Funerals are major social events. They are a time when family dispersed across New Zealand gather together after not seeing each other for a long time. Most Māori prefer to hold a tangi on the marae associated with the deceased or their family. The marae is carefully prepared to host mourners for several days, with arrangements made for accommodation, food, and ceremonial needs. While practices differ from one region to another, certain traditions are universal: the tūpāpaku and the grieving family are seldom left alone, and mourners remain in close attendance day and night until the time of burial. Māori individuals often wail in front of the open coffin and laugh between ceremonies to relieve their sadness.

Māori Burial Customs and Cemeteries

During “tangihanga” (traditional Māori funerals) the body of the deceased is placed before a “marae” (meeting house) and a long meeting called a “tangi” is held to hasten the journey of the soul to the land of spirits.

The Māori used to practice what anthropologists call "secondary burial" involving two interments of a corpse or its remains. Traditionally, the dying and deceased were brought to a shelter on the marae. The body was laid out on mats to receive mourners who arrived in hapu, or tribal, groups. After a week or two, the body was wrapped in mats and buried in a cave, tree, or ground. Different Māori groups had different practices After a year or two, the ariki often had the body exhumed. The bones were scraped clean and painted with red ochre before being taken from settlement to settlement for a second period of mourning. Then, the bones were given a second burial in a sacred place. It was believed that the spirits of the dead made a voyage to their final abode: a vague and mysterious underworld. In the case of dead whales care has traditionally been given to bury the whales so their head or oriented in the direction of the sea.

Many marae have an urupā (cemetery) nearby, regarded as one of the most tapu (sacred) places in Māori society. Activities such as eating, drinking, or smoking — which are noa (free from tapu) — are strictly forbidden within its boundaries. After leaving the urupā, people wash their hands with water to remove or lessen the tapu, returning themselves to a state of noa. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025