MĀORI

The Māori are the indigenous people of New Zealand. Today, they form about 18 percent of the country's population. Their traditional dress and forms of expression such as the Haka are not only representations of their culture but have become symbols of New Zealand as a whole. Throughout New Zealand, the influence of the Māori culture is also evident in the names of streets, towns, rivers, and mountains, as well as in art, literature, and music. The Māori name for New Zealand — Aotearoa, which is commonly translated as "Land of the Long White Cloud" — is now one of the official names of New Zealand

The Māori (pronounced MOW-ree) are descendants of Polynesian tribes that arrived in New Zealand about 800 years ago. Māori means "ordinary people" which distinguishes them from “pakeha”, a term that means "non-Māori" and is used to describe whites. After contact with Europeans, the Māori began using the term tangata Māori, meaning "usual or ordinary people," to refer to themselves. Their traditional ethnonym (the name by which a people or ethnic group is known) since the arrival of Europeans has been Te Māori. [Source: Yva Momatiuk, National Geographic, January 1984; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

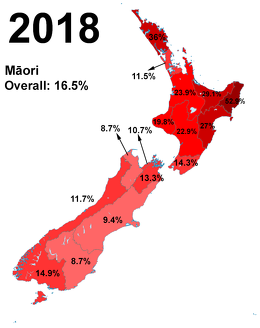

New Zealand consists of two islands, the North Island and the South Island. The topography of the North Island is hilly with areas of flat, rolling terrain. The South Island is larger and more mountainous than the North Island. The vast majority (86 percent) of present-day Māori live on the North Island. Most Māori live on the northern half of the North Island, particularly around Rotorua, Taupo, Waikato, Northland, East Cape, Taranaki and Wanganui. Many New Zealand cities, especially Auckland, have large Māori populations.

The Māori are not one a single people but a number of groups. The Māori word for each group is iwi , and there are well over one hundred Māori iwi. Among the 40 or so major groups, are the Taunui, from the central North Island, and the Te Atiaw on the northern part of South Island. The largest Māori iwi is Ngāpuhi, with over 184,000 affiliated members according to the 2023 census. They are based in the Northland region of the North Island and numbered 122,211 in the 2006 census.. Following Ngāpuhi in size are Ngāti Porou and Ngāti Kahungunu.

Culturally, Māori are Polynesians, most closely related to eastern Polynesians. They have their own language, which is spoken with a staccato clip and is similar to native languages spoken in Tahiti and the Cook Islands. Their way of speaking English is distinct and has many unique words and expressions. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ]

Books: “Māori of New Zealand” by A. J. Metge (1967); “The Māori” by W. Forman and D. Lewis (1984); “An Introduction to Māori Religion” by J. Irwin (1984); “Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori Values by Sidney M. Mead and Hirini Moko Mead (Wellington: Huia, 2003); “A Study of Māori Ceremonial Gatherings” by Anne Salmond, (Wellington: Reed, 1975); “Te Marae: a Guide to Customs & Protocol” by Hiwi Tauroa and Pat Tauroa (North Shore: Raupo, 2009)

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST EUROPEAN SETTLERS IN NEW ZEALAND ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI KINGS AND QUEENS: KINGITANGA, LIVES, REIGNS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN THE PACIFIC REGION, POLYNESIA AND MELANESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI TATTOOS: HISTORY, HOW THEY WERE MADE, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WAKA (MĀORI CANOES): HISTORY, TYPES, ART, HOW THEY ARE MADE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Māori Population

The estimated Māori ethnic population in New Zealand was approximately 904,100 at the end of 2023, representing about 17.8 percent of the total population. By mid-2024, this had risen to over 911,000, with some estimates suggesting the number of people of Māori descent is now over one million. Projections infer that by 2043, about 21 percent of all New Zealanders will identify as Māori.

Māori ethnicity refers to people who self-identify as Māori, indicating a cultural affiliation. At least some of those who self-identify as Māori are varying degrees of mixed blood. Māori descent is a broader concept based on whakapapa (genealogy) and is a measure of ancestry, not necessarily cultural identification.

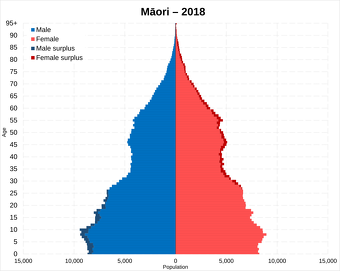

The Māori population has experienced a significant increase since its lowest point in the 1890s. Between 2018 and 2023 the number of people of Māori descent increased from from 12.5 percent to 17.8 percent of the population — a quite significant jump. The Māori population is younger on average than the overall population, with over 70 percent of those of Māori descent being under 40 years old and 25 percent are under 20 years. There is a sizable number of Māori in Australia. In 2016 Australia hosted to 142,000 people with Māori ancestry, according to New Zealand's Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

When Captain Cook visited New Zealand in 1769 the indigenous population was probably between 200,000 and 250,000. The population declined after contact with Europeans. In the early 19th century, at the end of their war against European encroachment, the Māori in New Zealand numbered about 100,000. The number later dwindled to 40,000. Their numbers began to recover at the beginning of the 20th century and reached 300,000 in the 1960s and 500,000 in the 1990s. A total of 565,329 Māori were counted in the 2006 census.

Māori Character — and Warrior Ethos?

Cultural practices such as The Haka give the impression that the Māori have an aggressive side, which maybe they do have along with a lot of other groups, but for the most part they are very relaxed, smiling, and friendly. They are also very proud and don't like being stereotyped by non-Māori. Traditional Māori war posturing and battle recitations are used today in ceremonial welcomes and this sometimes lead to an association of the Māori with a warrior ethos. Many Māori carvings and dances feature men sticking out their tongues, which has been regarded as a taunt and a challenge.

In the old days Māori men devoted much of their energy to warfare. Their traditional weapons included the “patu” (jade club) and “taiaha” (fighting staff). From an early age Māori males were taught it is better to "die like a shark, fighting to the end than to give up limply like an octopus."

Explaining the Māori warrior ethos, the Māori actor Temuera Morrison once said, "A guy puts a piupiu on, he gets a tatoo, he grabs a taiaha. All of a sudden something comes over him. He's got to run out and do his challenge...he starts running like this, 'Tu! Tu! [invocation of the god of war Tumatauengal]. So, what is it? Something in our blood. It's that “ihi” [power] and that “wehi” [terribleness] and that wonder. That “mana” from our ancestors who came here and named the mountains."

Māori Language

In 2023, over 213,000 New Zealanders could carry on a conversation in te reo Māori — the Ma ori language. This is up from 185,955 speakers in the 2018 Census and a 15.0 percent increase between 2018 and 2023. Most of the speakers are Māori. If all of them were they’ make up about 22 percent of the Māori population. But there are some whites who speak Māori. Māori was spoken by about one-third of the Māori population in the 1970s. In 2006, nearly 25 percent of the Māori population indicated that they could hold a conversation in Māori.

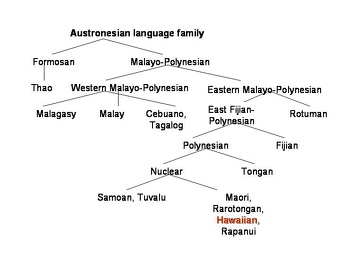

The Māori language belongs to the Tahitic or Eastern Oceanic branch of the Eastern Polynesian language group of the Malayo-Polynesian language family along with Hawaiian, Samoan, and Tongan. Māori and Tahitian are very similar. Early European explorers to the region commented on how closely related the two languages were. They were the first two Polynesian languages to have printed books in the early 19th century. *\

The Malayo-Polynesian language family forms the largest branch of the Austronesian language family, spoken by approximately 385 million people in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Ocean, and on the island of Madagascar. This language group includes major languages such as Indonesian, Malay, Javanese, and Tagalog, and is characterized by features like affixation, reduplication, and limited consonant clusters. [Source: Christopher Latham“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

According to Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language: No single dialect has emerged as the basis for a standard form of Māori. Tribal variation in pronunciation is shown in such pairs as “inanga–inaka” (a kind of fish), “mingimingi– mikimiki” (an evergreen shrub), and the place-name “Waitangi–Waitaki”. In each of these cases, “ŋ” is a North Island equivalent of a South Island “k”. In words conventionally spelt with wh (whare, kowhai), some tribes use a sound approximating to “f”, others a sound approximating to “hw”. [Source: Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language, 1998, Oxford University Press 1998]

Māori has the consonants “p, t, k, m, n, ŋ, f, h, r, w” and the five vowels “i, ɛ, a, ɔ, u”, which can be either long or short. It also permits a maximum of one consonant sound before any vowel. Consequently, loanwords from English may undergo considerable change: sheep to “hipi”, Bible to “paipera”, London to “Ranana”. The written consonant cluster “ng” is pronounced “ŋ”, as in sing, whether initial or medial. The Māori “r” in many words corresponds to Hawaiian and Samoan “l”: aroha, Hawaiian aloha love; whare, Samoan fale house.

History of the Māori Language

Prior to European colonization of New Zealand, there were two distinct Māori dialects: North Island Māori; and South Island Māori, which is now extinct. According to Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language: The Māori language was unwritten before the arrival in the early 19th century of British missionaries, who, in creating a written form for the language, did not always successfully equate its phonemes with the nearest equivalents in English. [Source: Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language, 1998, Oxford University Press 1998]

Most Māori are also fluent English speakers. A major feature of the work of early missionaries was the decision that vowel length in Māori did not need to be reflected in spelling (although diacritical marks have since been optional). Some present-day scholars of Māori have adopted a system of doubling long vowels: Maaori instead of Māori or Māori; kaakaa instead of kaka or kaka (parrot); kaakaapoo instead of kakapo or kakapō. However, since most printing of the language shows the older conventions, it seems likely that the missionaries’ style will prevail.

From the beginning, European settlers adopted Māori names for physical features and tribal settlements, but such names came to be pronounced with varying degrees of adaptation. Thus, the place-name Paekakariki, pronounced /paɛˈkakariki/ by the Māori, was Anglicized to /ˌpaɪkɒkəˈriːkiː/ and frequently reduced to the disyllabic /ˈpaɪkɒk/. The place-name Whangarei /ˈfaŋarɛi;/ was Anglicized to /ˈwɒŋəˈrei/. Most of the Māori names for the distinctive flora (kowhai, nikau, pohutukawa, rimu, totara) and fauna (kiwi, takahe, tuatara, weta) were also adopted and varyingly adapted into NZE. The issue of how far English-speakers should attempt to adopt native Māori pronunciations of such words has, for many years, been a major point of linguistic discussion in New Zealand. Broadcasting now attempts, not always successfully, to use a Māori pronunciation at all times.

In the later 19th century and early 20th century, the use of Māori was officially discouraged in schools. In 1867, New Zealand passed the Native Schools Act, outlawing the use of the Māori language in schools. Teachers and school administrators beat students who dared to speak their mother tongue. Those abused Māori children became Māori parents; trying to protect their own children from the same fate, many discouraged the use of the Māori language, first in public and then at home. The number of native speakers dwindled, and the language was at risk of being lost.“Everything during that period was learning how to be a colonizer,” says Tāme Iti , a renowned Māori activist and artist. [Source: Aroha Awarau, National Geographic, June 29, 2024]

But at the time many Māori concurred with this policy, seeing English as the language which was likely to give their children the greater advantage in later life. Today, all Māori speak English, but few Pakehas (white New Zealanders) and a diminishing number of Māori speak Māori with any great fluency, although attempts are now being made to give greater prominence to Māori language and culture. In an effort to keep their language alive the Māori have started language-immersion child-care centers called kohanga reo, or language nests, "where kids spend te day with fluent elders." Preschools that offer instruction in Māori language have sprung up all over the country at a rapid rate as a result of Māori activism. [Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999 /=]

How Māori Have Kept Their Language and Culture Alive

In more recent times, there has been a resurgence in the use of Māori as a marker of ethnic and cultural identity and many Māori people aim at bilingualism. Māori has now been recognized as an official language in the courts. Aroha Awarau, a Māori, wrote in National Geographic: In the early 1970s, a contingent of young, urban, and university-educated Māori began to form a movement...These activists called themselves Nga Tamatoa, or Young Warriors. Along with other regional groups, they organized against the New Zealand government’s marginalization and forced assimilation of Māori communities, starting with policies designed to stem the use of te reo Māori. [Source: Aroha Awarau, National Geographic, June 29, 2024]

In 1972, Tāme Iti (Ngai Tuhoe, Waikato, Te Arawa) and fellow Nga Tamatoa members marched with the Te Reo Māori Society to the steps of the New Zealand Parliament in Wellington. The contingent carried a petition, signed by more than 30,000 people, that called for Māori to be taught in all public schools. The highly visible nature of the protest, Iti believes, imbued Māori communities across Aotearoa with the confidence to reclaim te reo Māori.

Dame Iritana Te Rangi Tāwhiwhirangi (Ngati Porou, Ngati Kahungunu, Ngapuhi) was a founder and instrumental leader of the movement’s first major success: Kohanga Reo. Opened in 1982, the Kohanga Reo model was one of commitment. Parents and toddlers were expected to speak only te reo both in the classroom and at home, and the curriculum focused solely on Māori history and culture. Elders and other proficient language speakers led the classes. Translated in English to “language nest,” the Kohanga Reo was the first program of its kind to use total language and cultural immersion. For Māori communities, the schools were a revelation.

According to Tawhiwhirangi (Ngati Porou, Ngati Kahungunu, Ngapuhi), the program started with five schools and within three years expanded to more than 300 locations. The rapid spread of Kohanga Reo marked an unprecedented success of cultural reclamation. For Tawhiwhirangi, it showed the widespread, pent-up desire Māori families felt to educate their children according to their own non-colonial standards.

Why did Kohanga Reo fly? The difference-maker, she said, was that the Kohanga Reo, particularly in the early years, were entirely community led. Families raised the money to rent or buy classroom spaces, and volunteers planned and taught classes. The New Zealand government was intentionally uninvolved with curriculum and oversight. At the early nurturing stage in particular, Tawhiwhirangi says, language starts at home.

Māori families soon recognized the work could not begin and end with the Kohanga Reo. In 1985, in Kaipara’s corner of Aotearoa, a group of Māori elders and educators founded Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Hoani Waititi—the first te reo immersion school for primary school students. Meanwhile, a contingent that included Tawhiwhirangi and Karetu, who was appointed Māori language commissioner in 1987, organized the passage of the Māori Language Act, which gave te reo Māori official status alongside English; Similar systems have been adopted for the Hawaiian language in Hawaii and by the Puyallup Tribe in Washington State to the Sámi in Finland,

Māori Holidays

Christian Māori observe the major Christian holidays alongside other New Zealanders. In traditional Māori society, however, holidays in the Western sense did not exist—rituals and ceremonies followed a religious calendar linked to seasonal cycles, such as planting, harvesting, and food gathering. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

A particularly significant and sometimes contentious national holiday for Māori is Waitangi Day (6 February), which commemorates the 1840 signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, intended to protect Māori rights and privileges. In 1994, protests by Māori activists disrupted the national celebrations, prompting the government to cancel the official events that year.

In 2021, New Zealand has made Matariki, the Māori new year celebration, the first public holiday that honors Māori culture. According to the Christian Science Monitor: Matariki is the Māori name for the Pleiades star cluster, which rises in the Southern Hemisphere around midwinter. This historically marks the start of the new year for mainland New Zealand’s Indigenous people. Local councils have been organizing Matariki celebrations and raising awareness about the tradition since the early 2000s, but past efforts to recognize the constellation’s reappearance as an official holiday have failed. [Source: Lindsey McGinnis, Christian Science Monitor, February 20, 2021]

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the first official Matariki will be celebrated June 24, 2022, and future dates will be determined by the newly formed Matariki advisory group in compliance with the Māori lunar calendar. It will also advise on how to celebrate the event, considering regional differences in tribes’ traditions, and develop resources to educate the public about Matariki’s meaning, said chair Rangiānehu Mātāmua, a professor who specializes in Māori astronomy.

Māori Culture and Sports

Traditionally, Māori people lived off agriculture, hunting, and fishing. They have strong attachments to the Māori language, culture, and customs. Tattooing, carving, and weaving were developed arts in Māori society, and their war chants (The Haka) are still performed today. The famous opera singer Dame Kiri Te Kanawa is part Māori and has a Māori name. In the mid-1990s, several Māori tribes held a tribunal to discuss gaining copyrights to traditional Māori songs, myths, dances and carvings. [Source: World Encyclopedia 2005, originally published by Oxford University Press 2005]

Singing is an important part of Māori culture and is often used in place of speaking during important events such as ceremonies and welcomes. The Māori term waiata covers a wide variety of situations for singing including chants, hymns and laments. A simple waiata that many New Zealanders know by heart is Te Aroha. Another, known well around the world is Pōkarekare Ana, famously performed by Kiri Te Kanawa. Within the world of pop music, the 1980s hit song Poi Eblended traditional Māori song with contemporary styles such as hip-hop.

The Māori are into rugby. In addition to the All Blacks — the New Zealand national rugby team — there is a Māori All Blacks teams. The Māori All Blacks are a representative rugby team for which a prerequisite for playing is having Māori whakapapa (genealogy or ancestry). The New Zealand Māori team competes in international competitions. War canoe races are a popular form of recreation and entertainment. Traditionally, there were competitions among men in Māori society that emphasized aggressiveness and provided practice for real-life conflicts. Modern Māori have become consumers and producers of video, television, and film. Traditional storytelling and dance performances have been preserved by the Māori people and continue to serve as a form of entertainment today. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Māori Folklore and Mythology

Māori myths, histories, genealogies, knowledge about the ancestors and their canoe journeys, and information about things like birds, fish and animals have traditionally been passed down from generation to generation in chants that were learned by rote by Māori when they were young. Sometimes these chants were accompanied by music from flutes played with the nose. Māori folklore focuses on pairs of opposites, such as earth and sky, life and death, and male and female. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Māori legends recount how the natural world came to be. New Zealanders grow up hearing these stories, which have been passed down for many generations. One example is the creation myth about Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother), who embraced each other in darkness. Their son, Tāne Mahuta, the god of forests, pushed his parents apart to create space for Te Ao, light, to exist, opening the way for the creation of human life. Tane was responsible for creating the first woman and man.

Another popular legend is the story of Māui, a god famous for his clever and daring exploits. One of his most well-known acts is catching the sun with ropes to slow it down and lengthen the day for more time to work and play. A similar tale tells of Māui catching a giant fish with a fishhook carved from his grandmother’s jawbone. The fish became the North Island of Aotearoa, and his boat became the South Island.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025