Home | Category: History and Religion / Maori

EARLY MĀORI

Māori are regarded as the indigenous people of New Zealand. They are of Polynesian descent. Calling their new homeland Aotearoa ("land of the long white cloud"), they Māori settled in communities called kaingas, mostly located on North Island and have passed on their culture and history orally from past generations to the present. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

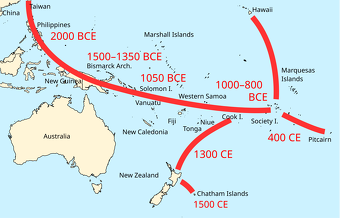

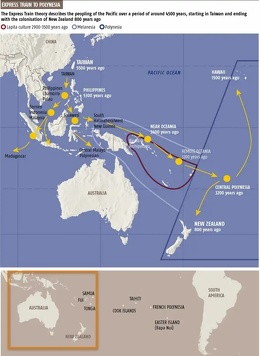

Genetic and archaeological evidence suggests that the ancestors of the Māori originally set out from mainland Southeast Asia around 6,000 years ago, hopped from island to island, starting with Taiwan, and finally making it to New Zealand. Genetic studies indicate that closest genetic relatives of the Māori are found in Taiwan. Archaeologists refer to two branches of Māori, the archaic and the traditional. The archaic Māori were likely the original inhabitants of New Zealand who relied on the moa, a large, flightless bird that they hunted into extinction. The artifacts that remain of this culture can be dated to around ad 1000 and are significantly different from those of the traditional Māori.

New Zealand consists of two islands, the North Island and the South Island. The topography of the North Island is hilly with areas of flat, rolling terrain. The South Island is larger and more mountainous than the North Island. Prior to human habitation of the islands, there were extensive forests. These forests provided a resources for the ancient Māori who lived on both islands but were more numerous on the North Island, which is warmer. They remained relatively isolated from external contact until 1769, when the English navigator and explorer Captain James Cook (1728–79) initiated a permanent European presence in New Zealand.

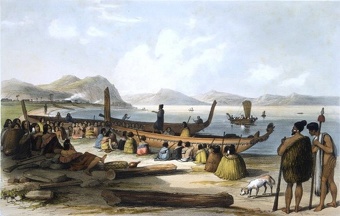

While New Zealand presented a marked difference in climate to more tropical Polynesian islands, it appears that the influence of cultural practice usurps that of climate with respect to the level of cultural importance given to the traditional sacred areas of villages. Records from early European visitors, such as AF Angas’ drawings, clearly indicate that a preference for a life centred around outdoor spaces and activities continued at least up to the 1800s. But that is not to say that climate was not important when choosing living places. The North Island, especially in the north — where there is a more temperate climate — was more intensively inhabited than the South Island, which had a colder alpine climate. It seems likely that the South Island was originally settled for specific resource exploitation such as seals and moas. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria, University of Wellington, 2012]

Related Articles:

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PEOPLE MIGRATE TO AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PEOPLE IN AUSTRALIA factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PEOPLE IN OCEANIA AND THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

LAPITA CULTURE AND THE ARRIVAL OF ASIANS IN THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

EXPANSION OF PEOPLE ACROSS THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST EUROPEAN SETTLERS IN NEW ZEALAND ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI TATTOOS: HISTORY, HOW THEY WERE MADE, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WAKA (MĀORI CANOES): HISTORY, TYPES, ART, HOW THEY ARE MADE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Arrival of the Māori in New Zealand

The Māori arrived in New Zealand in several waves. Christopher Latham wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ The early arrivals, the Moriori, subsisted mainly by fishing and hunting the moa and other birds that are now extinct. The final (pre-European) immigration was that of the "seven canoes of the great fleet." The people of the great fleet assimilated the original inhabitants by marriage and conquest. The immigrants of 1350 arrived with their own domesticated plants and animals (several of which did not survive the transition from a tropical to a temperate climate), and they subsequently developed into the Māori of the present historical period. [Source: Christopher Latham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Owing to the absence of written records, it is impossible to give any accurate date for their arrival, but according to Māori oral traditions, they migrated from other Pacific islands to New Zealand several centuries before any Europeans came, with the chief Māori migration taking place about 1350. It seems likely, however, that the Māori arrived from Southeast Asia as early as the end of the 10th century. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, 2006]

Māori oral history states that the original homeland of the traditional Māori was in the Society Islands of Polynesia, and that the Māori migrants left to escape warfare and the demands of excessive tribute. The traditional Māori are believed to have migrated to the North Island around the 12th century. This is confirmed by archaeological dating techniques as well as the genealogical histories of the Māori. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: At the time people arrived in New Zealand’, people had already been living in Australia for some fifty thousand years. They’d been in continental North America for at least ten thousand years, and in Hawaii, which is even more remote than New Zealand, for more than five hundred years. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, December 22 & 29, 2014]

Related Articles: FIRST PEOPLE IN THE OCEANIA AND THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com ; EXPANSION OF PEOPLE ACROSS THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com

Māori Beliefs About Their Origin

All Māori believe they are descendants of people who arrived on seven great canoes that came from the mother island of Hawaiki in A.D. 1350. Hawaiki is most likely Tahiti or one of the Cook Islands.

According to Māori legend, New Zealand was created by the demigod Maui, who persuaded his brothers to sail to unknown waters south of their homeland on a fishing trip. Using his mother's jawbone for a hook and his own blood for bait, Maui caught a colossal fish (the North Island of New Zealand).

The Māori settled primarily on the North Island of New Zealand, which they called “Te Ika a Maui” (the Fish of Maui). The South Island is referred to as both “Te Wai Pounamu” (the Water of Jade) and Maui's canoe.

Adele Whyte, the Tuapapa Putaiao Māori Fellow at Victoria University in Wellington, said: "The story I was told when I was growing up is that there was a fleet of seven great waka (canoes) that came to New Zealand," she said. "Every tribe knows which waka their ancestors arrived in. My ancestors were in a waka called Takitimu. There might have been 20 people travelling in a canoe the size of a waka. Seven waka, that's about 140 people. And if, as we think, about half or 56 of these people happen to be women, it does seem to tie in."

See Separate Article: WAKA (MĀORI CANOES): HISTORY, TYPES, ART, HOW THEY ARE MADE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Genetic Markers Say Māori Men and Women from Different Homelands

Male and female ancestors of today's Māori appear to have originated from different places according to genetic analysis by Adele Whyte at Victoria University in Wellington, and her supervisor Professor Geoff Chambers. ABC-TV reported; By comparing the DNA of people from Asia, across the Pacific Ocean and New Zealand, Whyte and Chambers have revealed a 'living genetic map' of ancient Māori migration routes. However the research also brings startlingly new evidence that as Māori ancestors migrated one group of islands to the next, men from Melanesian communities joined the boats. This changed the genetic mix, and lead to the differences observed in the genetic make-up of today's Māori men and women. [Source: Mark Horstman, ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), March 27, 2003

The research involved two separate genetic mapping processes. The Southeast Asian homeland was confirmed by Chambers' research into the frequency of two different genes that influence the body's reaction to alcohol. He found that while Asian people have both gene types, Māori and Pacific Islanders have inherited only one. He looked back along the trail of migration to try and work out where the gene was lost. The indigenous people from Taiwan have both genes, but a lower frequency of one - the very gene that the Māori now lack. "We think this one was lost at the first step of migration, when people left what is now Taiwan," Chambers told ABC Science Online.

The second mapping process involved Whyte's examination of sex-linked genetic markers, namely mitochondrial DNA in women, and Y-chromosomes in men. The research found that in addition to the alcohol genes, female Māori have other genetic markers which confirm their ancient Asian origin. To her surprise, however, the men have genetic markers that show a Melanesian ancestry. "As a result of intermarriage along the migration trail, the signatures of the mitochondrial DNA from women have stayed more 'island south-east Asian', and the Y-chromosomes are more Melanesian," Whyte told ABC Science Online "We think both men and women set off together, and recruited local guides who were probably men. Women stayed with the south-east Asian populations, and Melanesian men were recruited along the way."

Whyte also analysed the 'haplotypes' (groups of closely linked genes) carried on mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited only through the female line. Each population has a unique range of haplotypes. While Europeans have over 100 haplotypes in a particular region of DNA, studies so far have only found four different Māori haplotypes in the same region. "The reason for this difference is what we call a genetic bottleneck. When people leave an island to go to the next island, obviously not everybody gets on the boat, so some of the genetic diversity is being lost," she said. "Some of the maternal lineages may not have got on the boat, so they're not carried on to the next place." Whyte has now identified 10 haplotypes in New Zealand Māori. "From that we have worked out that 56 women came to New Zealand to create the diversity of today's population," she added. Her conuslions are consistent

Arrival of the Māori in New Zealand Revealed in Antarctic Ice

Researchers have found soot preserved in Antarctic ice that they have linked to fires set in New Zealand by Māori settlers. Ice cores drilled in an island off the Antarctic Peninsula preserved soot from around A.D. 1300 which originated the ice 6,000 kilometers away in New Zealand. [Source: New York Times, October 9, 2021

Kate Evans wrote in Eos Science News: When the Polynesian ancestors of the Māori first arrived in New Zealand, they used fire to clear some of the forest for agriculture, to facilitate hunting, to claim occupation of territories, and to honor their ancestor Mahuika, the goddess of fire. The smoke from those fires traveled much farther than anyone imagined. A recent study in Nature, using an array of ice core records from Antarctica, has revealed that black carbon from those fires was carried on the westerly winds halfway around the Southern Ocean and deposited in the ice covering an island off the Antarctic Peninsula. [Source: Kate Evans, Eos Science News, American Geophysical Union, October 26, 2021

Lead author Joe McConnell from the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Reno, Nev., said the research team didn’t set out to look for anthropogenic impacts in Antarctica. They planned to map natural variations in soot deposition in the ice over the past 2,000 years using a sophisticated analysis technique developed in the DRI lab. The research was part of an effort to improve climate models. (Black carbon aerosols absorb light and contribute to atmospheric warming.) But when McConnell and his colleagues compared the ice core from James Ross Island to five others from different parts of the Antarctic mainland, they found something unexpected.

For the first 1,300 years, the ice cores all told the same story. But around 700 years ago—1297, plus or minus 30 years, to be precise—the core taken from the peninsular island sharply diverged from the rest. There, black carbon levels almost tripled over the ensuing centuries, whereas the ice cores from continental Antarctica stayed relatively stable.

Atmospheric modeling (using the powerful flexible particle dispersion model) showed that for the soot particles to have landed only on the Antarctic Peninsula—which sticks up like a thumb into the prevailing westerly flow—they had to have come from a landmass located south of 40° latitude. The only possible candidates were Patagonia, Tasmania, and New Zealand. “Anything that’s emitted at 40°–60° south is going to get caught up in that westerly belt and make a big doughnut around Antarctica,” said McConnell. “The beauty of this whole study is that the James Ross Island ice core in the peninsula is at least 1,000 kilometers away from any potential burning area.…It’s an unusual situation where the record is extremely sensitive to any changes in emissions from those three locations.”

When the scientists looked into the charcoal records from lake sediments in those places, they found that wetter climate conditions in both Tasmania and Patagonia during the past 700 years actually led to less burning than usual. Charcoal records from New Zealand, however, showed the opposite: a dramatic fire spike after 1300, just when the black carbon started appearing in the Antarctic Peninsula ice core. It’s also roughly when archaeological evidence suggests the first Māori arrived.

Life of the Early Māori

The Māori were originally settled primarily in the northern parts of North Island, New Zealand. South Island was much more sparsely settled. The Māori ate “kumara” (a kind of sweet potato), taro, gourds, yams and rats which they brought to New Zealand from their home islands in Polynesia. They also ate moas (ostrich-size birds that are now extinct), other birds (also extinct), seals, and fish. Food was kept in bird-house-like storehouses, called “whata” or “patuka”, that were elevated on a single post.

Initially, the Māori had some trouble adapting to New Zealand's temperate climate which was much cooler and wetter than the climate of the South Pacific Islands they originated from. They lost kumara and other plants to frost and found they could they could not plant crops year round as did on their home islands. Eventually they learned to store tubers in pits and plant the shoots in the spring. They also replaced their traditional bark clothing with woven-flax garments and made their homes smaller and warmer.

In coastal areas, the Māori people traditionally traveled by various types of canoes, including single-hulled, outriggerless canoes, as well as large, double-hulled canoes. Waka taua were large Māori war canoes powered by sails and paddles. The Māori ate dog as other Polynesians did and Māori chefs greatly prized their dogs skin cloaks. Even so Māori were very attached to and loved their dogs. In the old days. Māori used dogs to hunt kiwis. Caterpillars that ate sweet potato vines were a major pest.

Land ownership was communal, held by descent groups or tribes (iwi). Each group controlled its own territory and granted its members rights to use and occupy specific areas. Only the tribe as a whole could transfer or alienate land, and even then only with collective consent. Disputes over boundaries were a frequent cause of conflict. Within the tribe, the whānau (extended family) held rights to particular resources or parcels of land, which were passed down through generations. Non-members could be granted usage rights only with the permission of the group, reflecting the strong collective nature of Māori land tenure and kinship ties.

Traditional Māori Villages

In the past there were two types of Māori settlements: fortified (pā) and unfortified (kainga). The pa, where people took refuge during wartime, were typically situated on hills and protected by ditches, palisades, fighting platforms, and earthworks. Houses in the pa were tightly packed, often on artificial terraces. Kainga were unfortified hamlets consisting of five or six scattered houses (whare), a cooking shelter (kauta) with an earth oven (hangi), and one or two roofed storage pits (rua). Most farmsteads were enclosed by a courtyard with a pole fence. Most buildings were made of poles and thatch, though some were better constructed with posts and worked timber. [Source: Christopher Latham,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Māori villages traditionally have been orientated toward flat (or slightly lower) open ground, with the ‘back’ of the settlement closed in using the physical landscape, such as forest or higher ground. A social hierarchy has been associated to the layout, with restricted and sacred (tapu) uses near the entrance, and unrestricted and ordinary (noa) uses further into the settlement. [Source:Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria, University of Wellington, 2012]

The principle building has been is the marae atua (meeting house), near the entrance. Only structures and other spaces with tapu functions (such as the chief’s house) could front onto the marae atua, and helped to define this space. Other noa structures, such as cooking buildings and storage platforms, were kept at a distance from the marae atua so as not to disturb the tapu status.

Archaeological evidence in New Zealand suggests that early Māori people continued the cultural practices that they were accustomed to from Polynesia. These practices varied on different islands but had consistent themes such as those defining a hierarchy of outdoor spaces — the spaces between buildings — as the principle areas of ritual and community activity.

Archaeology magazine reported: On private Great Mercury Island off the northeast coast, archaeologists are excavating an early Māori site — dating to the second half of the 14th century, perhaps just decades after Polynesian seafarers first arrived. It appears to be a small fishing settlement, marked by thousands of stone artifacts, as well as fishhooks made from sea mammal teeth and the bones of moa, the large native birds that were hunted to extinction 100 years after human arrival. A number of oceanside sites such as this one are at risk from coastal erosion. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

In 2014, a “large piece of a 600-year-old canoe emerged from a beach on South Island. The canoe suggests connections with places across the South Pacific. It is made of local black pine, but employs a sophisticated oceangoing design with ribs and a girder, and has a carving of a turtle on the hull. Both the design and carving were unknown or rare in New Zealand at the time, and represent some sort of cultural continuity with the rest of Polynesia. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, January-February 2015]

Ancient Māori Economic Life and Agriculture

Traditionally, Māori subsistence was based on fishing, gathering, and horticulture, particularly the cultivation of sweet potatoes (kūmara), along with taro, yams, and gourds. Fishing involved the use of lines, nets, and traps, while birds were caught using spears and snares. Māori also gathered shellfish, berries, roots, shoots, and piths, and hunted rats for food. In regions with poor soil or during harsh seasons, fern roots were an important supplementary starch. Kūmara was typically planted in October and harvested in February or March, while winter was the key hunting season. Procuring food required considerable time and effort, reflecting the close relationship between Māori and their environment. [Source: Christopher Latham,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Māori tools and implements were made from stone and wood, with mechanical aids such as wedges, skids, lifting tackles, fire ploughs, and cord drills. Most items were highly decorated, reflecting the aesthetic and spiritual dimensions of craftsmanship. Major manufactured goods included flax mats, canoes, fishing gear, weapons, digging sticks, cloaks, and ornaments. Exchange in traditional Māori society was based on gift giving rather than fixed prices or currency. Goods and services were reciprocated according to social relationships and the concept of mana—spiritual prestige or power—was enhanced through generosity. Commonly exchanged items included food, ornaments, flax garments, stone, obsidian, and greenstone (pounamu). Coastal and inland groups traded sea and agricultural products for forest goods, while greenstone from the South Island’s west coast was exchanged for finished goods from the north.

Henry Fisher wrote: It seems the location of buildings was principally to define the spaces between them, which is contrary to the European approach to space design throughout the same time period. Further, these buildings only ever enclosed a single space, suggesting that they were not intended to operate in isolation to their surroundings. Reinforcing this hierarchy of spaces was a strict format for locating the individual built elements in the settlement, so that their purpose and the social ranking of the user-group were closely related to those of the surrounding spaces.

The orientation of the settlement as a whole related to important elements in the surrounding landscape. Land closest to the coast was often reserved for high-ranking’ activities and habitation, with a diminishing hierarchy attached to both land and activity as one moves closer to the centre of the island. In New Zealand there was a great deal of regional and local variation, but a generic pattern emerged that was informed by this Polynesian background. Initially, settlement across the two largest land masses has been described as ‘a constellation of “resource islands”’, connected by a network of seafaring coastal routes. Through time, the close connection to the coast became less marked, particularly as settlements moved further inland. There is evidence held in the oral history by the elders of many iwi suggesting a move away from the coast included — an attempt to evade the dangers of natural disasters, such as tidal surges and the recorded tsunami on the Nelson coastline in the 15th century. Over time, significant forms in the landscape, including mountains, forests, rivers and open land seemed to replace the coast–to-inland settlement layout.

Absence of Stone Architecture in Ancient Māori Settlements

A notable distinction between the sacred spaces of eastern Polynesian island cultures and those in New Zealand is the absence of stone platforms, sculptures, and altars. Examples of such structures include the ahu of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), on which the stone figures known as moai stood, and the stone and coral marae of Tahiti, which incorporated a stone ahu (altar). [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria, University of Wellington, 2012]

Deirdre Brown observes that the reasons for the absence of stone in the marae of New Zealand remain uncertain. One theory suggests that limited labour resources may have been a key factor, as considerable time and effort were required for subsistence activities. Indeed, there is evidence that Māori communities invested substantial energy in modifying the landscape for cultivation—such as the extensive gardens of Moikau Valley (Palliser Bay) and the canal system off the Wairau Bar (Fisher, 2012).

The lack of stone architecture in New Zealand may also reflect how material availability, climate, and cultural practices shaped early settlement patterns. Anne Salmond cites archaeological evidence from Houhora (Mt Camel) in Northland to illustrate how early Māori developed seasonal patterns of migration between semi-permanent sites. This mobility, driven by fluctuations in local climate and food resources, suggests that extended family groups may not have been inclined to devote the time and labour required to build structures from durable materials such as stone.

Moreover, New Zealand’s environment offered abundant hardwoods, providing a resilient and portable alternative to the softer timbers of tropical Polynesia, such as coconut and breadfruit. Ancestors and deities were—and continue to be—depicted in hardwood carvings, a practice that may have enabled communities to maintain spiritual continuity while remaining mobile. In effect, one could carry one’s ancestors and guardians. As settlements gradually became more permanent, the established tradition of wood carving persisted and evolved into a defining feature of Māori art and architecture.

Another likely factor is the limited number of suitable stone sources. Obsidian, basalt, and argillite were intensively quarried where available, and artefacts such as adze blades have been found across great distances. The wide reach of these trade networks, and the apparent prestige of those who controlled them, suggest that high-quality stone was both scarce and highly valued, further discouraging its use in large-scale construction.

Impact of the Māori on New Zealand's Animals

Humans arrived in New Zealand from Polynesia about A.D. 1300. They and the animals they brought with them, namely dogs and rats, were responsible for the exterminated many of New Zealand indigenous animals, including moas and at least 18 other species of bird including the flightless New Zealand goose, the Fjordland crested penguin, the giant rail (more than a meter tall) as well as several species of lizards and insects. The devastating ecological consequences of human arrival are well documented on many East Polynesian islands and show striking similarities in terms of deforestation and faunal extinctions or declines.

The first people to arrive on New Zealand found no large mammals: no deer, no antelope, no bears, or large cats or even kangaroos like in Australia. The only mammals were two species of small bat and the only predators were falcons, hawks, eagles and other meat-eating birds.

The colonization of New Zealand by human triggered a devastating transformation, also in a relatively short period of time. There was widespread deforestation. Overhunting contributed to widespread faunal extinctions and the decline of marine megafauna, fires destroyed lowland forests. The introduction of the , Pacific rat is believed have led to the extinction of bird and reptile species. [Source: Janet M. Wilmshurst Atholl J. Anderson, Thomas F. G. Higham, and Trevor H. Worthy, PNAS, June 3, 2008]

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: When the Māori showed up, there were nine species of moa in New Zealand, and it was also home to the world’s largest eagle — the Haast’s eagle — which preyed on them. Within a century or two, the Māori had hunted down all of the moa, and the Haast’s eagle, too, was gone. A Māori saying — “Ka ngaro i te ngaro a te moa” — translates as “Lost like the moa is lost.” [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, December 22 & 29, 2014]

In their ships, the Māori also brought with them Pacific rats, or kiore. These were New Zealand’s first introduced mammals (unless you count the people who brought them). The Māori intended to eat the kiore, but the rats multiplied and spread far faster than they could be consumed, along the way feasting on weta, young tuatara, and the eggs of ground-nesting birds. In what, in evolutionary terms, amounted to no time at all, several species of New Zealand’s native ducks, a couple of flightless rails, and two species of flightless geese were gone.

Māori Warfare

In the old days Māori men devoted much of their energy to warfare. Conflict between different different tribes and clans was common and often led to warfare. Competition for land and resources led to intermittent fighting between different Māori iwi (tribes) by the 1500s. The traditional Māori weapons included the “patu” (jade club) and “taiaha” (fighting staff). From an early age Māori males were taught it is better to "die like a shark, fighting to the end than to give up limply like an octopus."

Warfare played a big role in Māori life. Boys were expected to become warriors; fighting was tied to Māori cosmology and spirituality; and land disputes and voyages of conquest were commonplace."The occasion of war" for the Māori, wrote historian Jack Keegan, "was always a desire for revenge, which might or might not be satisfied by a raiding party finding or killing a single member of the enemy. Māori war parties could do battle in a very brutal way. After a public meeting in which 'offenses could be recounted vehemently,' warlike songs chanted and weapons displayed, the war party would set out." [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

"Male children from the earliest age," Keegan wrote, "were taught that insult, to say nothing of robbery or murder, was unforgivable, and the Māori were implacable in storing up a memory of a grievance, sometimes from generation to generation, that was satisfied when the enemy was killed, his body eaten and the head mounted on a palisade of the fortified village, where it would be symbolically insulted."

Māori began their encounters with feints and postures to size up their enemy. This led to human wave charges. "The great aim of these fast-running warriors," Keegan wrote, "was to chase straight on and never stop, only striking one blow at one man, so as to cripple him, so that those behind should be sure overtake and finish him. It was not uncommon for one man strong and swift of foot, when the enemy was fairly routed, to stab with a light spear ten or a dozen men in such a way as to insure their being overtaken and killed."

Warfare was clearly a part of life for early Māori though the degree is still disputed. There were clearly change in culture from central Polynesia that included surprise attacks and the development of the pa (defensive settlements). Pa are particular to New Zealand. They were sophisticated forms of defence used in conjunction with rahui (resource reserves to guard against increasing over-exploitation). The presence of the latter suggests that material resources were often in short supply, and access to key sources were carefully guarded. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria, University of Wellington, 2012]

See Hand Clubs Under MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

Cannibalism, Slavery and the Dark Side of Ancient Māori Culture

The Māori practiced slavery and cannibalism. The defeated were most often enslaved, killed, or eaten. Women and Children were the most likely persons to be spared. Penalties for crimes ran from gossip, reprimand, and sorcery to seizure of property, beating, and execution. |~|

Māori slavery, known as Mōkai or Taurekareka, created a class of servants with limited rights but were not a hereditary caste, as their children were born free. Slaves were usually captured enemies from different tribes. Treatment could vary, with some individuals showing notable independence and even integration into their host communities. The concept of Māori slavery is a nuanced one; some historians argue that the term "slavery" does not fully capture the variety of experiences and terms used to describe the status of captives. The system ended gradually after the Treaty of Waitangi, though the practice remained for some time.

In 1835, the peaceful Moriori people of Chaltham island 500 miles off the coast of New Zealand were slaughtered and enslaved by the Māori. Some European individuals were captured, kidnapped, or brought into Māori villages and became enslaved. Slaves were often tasked with heavy physical work. Some accounts noted mild treatment, while others documented instances of cruelty and hardship. Slaves were not prevented from escaping and could even choose to stay with their host communities after their captivity ended.

Māori used to eat people. It is said warriors often traveled lightly, ate off the land and “looked forward to the human source of supply and talked of how sweet the flesh of the enemy would taste. If the there was more flesh than they could consume the packed the meat into baskets and used slaves to bring it back to their villages. It is also the Māori practiced human sacrifices, which were held to secure the help of the gods. Māori likes to raid villages when people were sleeping. The victims ran off into the woods. After a few enemy were killed their bodies were butchered and carried away. Speed was important, They didn’t want their enemy to regroup.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Archaeology magazine, PNAS,Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025