Home | Category: History and Religion

EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND AFTER COOK

Captain James Cook was the first Europe navigators to extensively explore and survey Australia and New Zealand. He was the first to circumnavigate the two main islands of New Zealand. After Cook, the only Europeans that ventured to New Zealand for many years were rowdy whalers and sealers and escaped convicts from New South Wales (Australia). Some of these people began settling in New Zealand beginning around 1795 mostly in transient camps and homesteads characterized by lawlessness and disorganized rules of land ownership. As a rule convicts in Australia stayed clear of New Zealand because they had been told if they went there they would be eaten by cannibals.

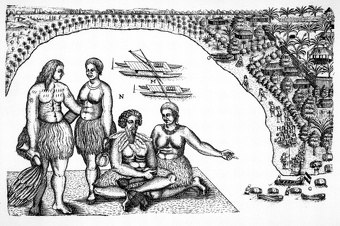

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, lumbering, seal hunting, and whaling attracted a few European settlers to New Zealand. In the 1790s-1800s, the main ingredients of Maori-European (Pakeha) contacts were whaling, timber and the spread of disease. In the 1790s, small European whaling settlements sprang up around the coast. In the 1820s, some British ships that dropped off convicts in Sydney stopped by New Zealand on the return journey to pick up timber from massive sequoia-like kauri pines, which was used to make mats and spars for tall sailing ships. The first Christian mission station was set up in the Bay of Islands in 1814 by Samuel Marsden, chaplain to the governor of New South Wales.

The U.K. only nominally claimed New Zealand and included it as part of New South Wales in Australia. Concerns about increasing lawlessness led the UK to appoint its first British Resident in New Zealand in 1832, although he had few legal powers. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

In 1840, there were about 2,000 Europeans and 115,000 Maori in New Zealand. By this time the Maori were trading crops and land with the Europeans in return for firearms, which fueled intense intertribal warfare. In 1840, the United Kingdom established British sovereignty through the Treaty of Waitangi signed that year with Maori chiefs. In the same year, selected groups from the United Kingdom began the colonization process.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

BRIEF HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND: NAMES, THEMES, HIGHLIGHTS, A TIMELINE ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA BY EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Sealers in New Zealand

Seals and sea lions were hunted another for their meat, oil and fur. Leather is sometimes made from seals. Commercial sealers traditionally drove the seals to a designated area and killed them with blow to soft parts of their skulls. Sealing — the hunting of seals — was widely practiced in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th century.

By that time Sealing was established around the coast of Australia and sealers travelled all around the Pacific. Fur seal skins were sold on the London market but more importantly was a tradeable commodity in China. When China had a monopoly on the international tea trade, sea skins were traded for tea. The Chinese found little of value in the normal trade goods offered by European traders. They demanded payment in gold. Seal skins were a good alternative. [Source: New Zealand History 1800 -1900, A blog to assist the students in Level 3 NCEA History at Wellington High School, February 28, 2008 ]

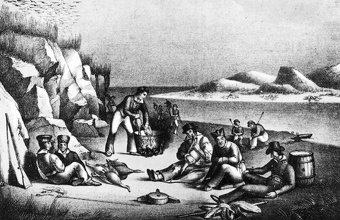

In New Zealand, the first Sealers set up camp in Dusky Sound (Fiordland) in 1792. Mainly ex-convicts, they were outfitted and supplied by entrepeneurs based in Port Jackson (Sydney). The job was simple. Kill as many Fur Seals as possible, skin them, cure the hide with salt and wait to be picked up. A good crew could return to Sydney with several thousand skins.

According to a blog on New Zealand history: Sealers were a rough and ready group. They settled in small groups around the southern coasts of both Islands. Sparsley populated by Maori their interaction remained relatively light. Most sealing operations were centred on the south coast of the North island, and both coasts of the South Island. These areas were lightly populated by Maori especially the South Island. This did not mean that their impact was not important but the gangs were not settlers. They lived close to seal colonies were there for a matter of weeks or months and left. They might return but it was an itinerant lifestyle and was often a different group of men. They rarely carried any trade goods thus there was little incentive for Maori to interact with them in anything more than a cursory nature. The impact of this interaction is limited by the areas that sealing took place.

For more on Sealers See FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Maori Versus the Colonists

In 1835, some Maori iwi from the North Island declared independence as the United Tribes of New Zealand. Fearing an impending French settlement and takeover, they asked the British for protection.

According to “CultureShock! New Zealand”:The Maori people describe themselves as the tangata whenua, the people of the land, and they are the original settlers in New Zealand. The first non-Polynesian settlers along the shores of New Zealand were sealers and whalers. Many of these seafarers took Maori ‘wives’ and their offspring would be the earliest New Zealanders of mixed lineage. With the arrival of increasing numbers of traders and permanent settlers, intermarriage between Maori and Pakeha (Europeans) became more common.[Source: Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Marshall Cavendish International, 2009]

Most Maori today will tell you of a European forebear in their whakapapa (genealogy), and many of them are proud of their European tupuna (ancestors). The sealers and whalers were followed by missionaries, agriculturalists, explorers, merchants and adventurers.

The rapid growth in the Pakeha population alarmed Maori chiefs and tensions escalated. The compromise between the British government and the Maori chiefs culminated in the Treaty of Waitangi (See Below) The influx of European settlers pressured the colonial administrators of New Zealand to make more land available. The Maori had reason to feel threatened. The Europeans had brought with them not just ‘civilisation’, but also firearms, alcohol and diseases against which the Maori population had little or no immunity.

Treaty of Waitangi

Concerned about the impact of firearms on their traditional way of life, Maori chiefs approached British government representatives in New Zealand with the idea of establishing a treaty that would stem the flow of settlers, end tribal warfare and maintain law and order. The British were anxious to make a deal as a way of preventing France or the United States from taking over New Zealand.

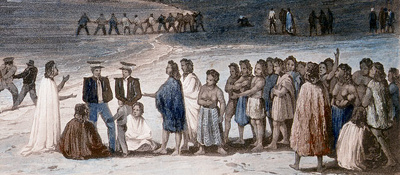

The ensuing agreement, the Treaty of Waitangi — signed on February 6, 1840 at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by representatives of the British crown and 500 Maori chiefs — promised the Maori the same rights as British subjects and protected their land and the rights of chiefs in return for giving the British crown the right to buy Maori land. There was also a clause that guaranteed Maori undisturbed ownership of their forests, fisheries, lands, and other possessions.

The treaty was signed at a time when Victorian humanitarian and the evangelical movement had a major influence on British foreign policy. It was originally intended to avoid "the disasters and the guilt of conflict with the Native Tribes," and was supposed to ensure that the Maori didn't suffer the same fate as native Americans in the United States, aborigines in Australia and Bantus in South Africa.

The British negotiated their protection in the Treaty of Waitangi, which was eventually signed by more than 500 different Maori chiefs, although many chiefs did not or were not asked to sign. In the English-language version of the treaty, the British thought the Maori ceded their land to the UK, but translations of the treaty appeared to give the British less authority, and land tenure issues stemming from the treaty are still present and being actively negotiated in New Zealand. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

According to the Treaty of Waitangi the Maori chiefs that signed it ceded some political powers to the British but maintained indigenous rights in perpetuity. The Maori chiefs who signed did so on behalf of their tribes but not all of them did. Maori land was to be sold directly to the British Crown to prevent unscrupulous purchasers from exploiting the Maori,

Waitangi Day, which commemorates the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, is regarded by many as New Zealand’s national day. Nonetheless, the treaty was not honored and terms that were supposed to benefit the Maori were instead used to screw them and annex New Zealand. Some Maori land was confiscated but most of it was sold and acquired through negotiated purchases. As new settlers arrived, the appetite of the Europeans for land increased.

Early British Settlers in New Zealand

The UK declared New Zealand a separate colony in 1841 and gave it limited self-government in 1852. Many settlers came to New Zealand in the 1830s, 40s and 50s when there were minor gold rushes in the Auckland area, the Coromandel Mountains and the South Island. Many missionaries also arrived during those years. Another gold rush occurred in 1861.

After the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, many settlers made the 12,000-mile ocean journey from Britain to New Zealand to begin a new life. These settlers were not convicts like the early settlers of Australian but middle-class Victorian English men and women who hoped to build a well-mannered paradise in the Southern Hemisphere.

Many people from Scotland, Ireland and countries in Europe also made the trip. Some were from other British colonies. One of them, Sir Charles Eliot, a former commissioner in Kenya, called New Zealand a "a white man's country in which native questions [would] present but little interest."

For much of New Zealand’s history, New Zealanders relied on Britain. Britain took most of Britain’s exports, was the source of most of its immigrants and provided New Zealand with its institutions and values.

In 2017, Archaeology magazine reported: The site of a future convention center in Christchurch is shedding light on the lives of the city’s first European settlers. Apparently, even back then, men were concerned with hair loss. Among the hundreds of artifacts found at the site in rubbish pits and deposits dating to the mid-19th century was a container of Russian Bears Grease. The quirky pharmaceutical product purportedly aided hair growth and prevented baldness — the underlying theory being that because bears were hairy, their fat could stimulate hair growth for humans. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2017]

New Zealand Company Settlers

In 1837, the New Zealand Association was formed in England, becoming the New Zealand Company in 1839. The organisation aimed to colonise New Zealand in accordance with the principles of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, an English theorist. Wakefield sought to establish a British colony in New Zealand based on the English social system. [Source: Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Marshall Cavendish International, 2009]

In 1840 the first New Zealand Company settlers arrived in Port Nicholson (today’s Wellington) and founded the first settlement. More settlers followed in the next few years, especially between 1840 and 1860 when the British government took a growing interest in New Zealand, and encouraged more Europeans to settle there.

The New Zealand Company established additional settlements in the South Island: in Nelson in 1842, in Dunedin in 1848 (with the cooperation of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland), and in Canterbury in 1850 (with the cooperation of the Church of England). Canterbury is considered the most successful of such settlements.[Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”, 2006]

Maori Rebellions

Different traditions of authority and land use led to a series of wars from the 1840s to the 1870s fought between Europeans and various Maori iwi. Along with disease, these conflicts halved the Maori population. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

Expanding European settlement led to conflict with Maori, most notably in the Maori land wars of the 1860s fought between the Maori and a combination of British administration forces and settlers. British and colonial forces eventually overcame determined Maori resistance. During this period, many Maori died from disease and warfare, much of it intertribal.

The Maori population felt threatened by the ever increasing number of Pakeha (foreign settlers) demanding more and more land. Many Maori refused to sell their land and live under British law. These sentiments produced tensions that mounted and erupted into rebellions and wars in the North Island in the 1860s.

There were two major rebellions: one in 1860 and another from 1863 to 1881. The Maori jade clubs and spears were no match for British guns and both rebellions were put down. When the Maori armed themselves with firearms instead of traditional weapons, intertribal raids resulted in more deaths and casualties. When the fighting was over the Maori were a defeated and largely dispossessed people.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New Zealand Tourism Board, Wikipedia, Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet, BBC, CNN and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025