Home | Category: History and Religion

NAMES FOR NEW ZEALAND AND ITS PEOPLE

The Coat of Arms of New Zealand depict a shield with four quadrants divided by a central "pale"; The first quadrant depicts the four stars on the flag of New Zealand; the second quadrant depicts a golden fleece, representing the nation's farming industry; the third depicts a sheaf of wheat for agriculture; and the fourth quadrant depicts crossed hammers for mining; The central pale depicts three galleys, representing New Zealand's maritime nature and also the Cook Strait; The Dexter supporter is a European woman carrying the flag of New Zealand, while the Sinister supporter is a Maori Warrior holding a Taiaha (Fighting weapon) and wearing a Kaitaka (flax cloak); The Shield is topped by the Crown of St; Edward, the Monarch of New Zealand's Crown; Below is a scroll with "New Zealand" on it, behind which (constituting the "heraldic compartment" on which the supporters stand) are two fern branches

Official Country Name: New Zealand, abbreviation: NZ.

Nationality: Noun—New Zealander(s). Adjective—New Zealand.

The Maori are the indigenous people of New Zealand. Their name for New Zealand is “Aotearoa”("Land of the Long White Cloud").

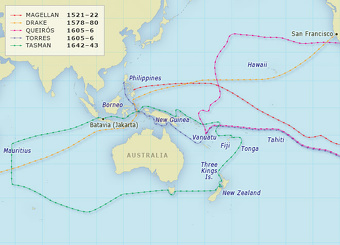

New Zealand is a Dutch anglicized name. Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to reach New Zealand in 1642. He named it Staten Landt, but Dutch cartographers renamed it Nova Zeelandia in 1645 after the Dutch coastal province of Zeeland. British explorer Captain James Cook subsequently anglicized the name to New Zealand when he mapped the islands in 1769. [Source: CIA World Factbook 2023]

New Zealand is sometimes nicknamed Way Down Under (it is further south than Down Under Australia) or the Godzone (a reference to the fact it is so beautiful).

Kiwi is a term that can technically can be used to refer to any New Zealander but is usually not used to refer to Maori. The name derived from the rare flightless bird unique to New Zealand. Kiwi fruit was originally known as the Chinese goose-berry and renamed to reflect its connection with New Zealand. People from New Zealand also refer to themselves as "En Zedders," a name based on the abbreviation "NZ" ("Z" is pronounced "zed" in New Zealand, as it is in Britain). The Maori word "pakeha" is used for New Zealanders of European descent.

New Zealand Finally Gives It Main Islands Official — and Official Maori — Names

Before 2013, The North and South Islands of New Zealand had been named, officially. In 2013 they were given official names and Maori names were equal status. Associated Press reported: Eight hundred years after the Maori first arrived in New Zealand, and 370 years after Europeans spied its shores, the South Pacific nation's major land masses will finally get official names. For generations, the two main islands have been called the North Island and the South Island. They have also appeared that way on maps and charts. But in recent years, officials discovered an oversight: the islands had never been formally assigned the monikers. [Source: Associated Press, October 10, 2013]

In October 2013, the land information minister, Maurice Williamson, announced that the North Island and South Island names would become official. Equal status was be given to the alternate Maori names: Te Ika-a-Maui ("the fish of Maui") for the North and Te Waipounamu ("the waters of greenstone") for the South.

Don Grant, chairman of the New Zealand Geographic Board, said the country had an informal process for naming places before 1946, when the formal process was set up. He said the Maori names for the islands had been the same since Europeans first arrived, but the English names had changed over time. On some early maps, he said, the islands were called New Ulster and New Munster, after the Irish provinces. The South Island was also sometimes called the Middle Island, a reference to the much smaller Stewart Island, which is even further south.

Grant said the North Island and South Island names became widely accepted after they were endorsed by an MP in 1907. But he said the names never became official, perhaps because there was no controversy or question about them. At least, that is, until 2004, when somebody challenged the South Island name, saying it should be renamed to its Maori moniker. Grant said that this was when the board first discovered that neither island had an official name.

But there were more delays. After the board studied the issue, a 2008 law change inadvertently prevented places from being given dual names. So the board waited until 2012 when the law was fixed. Then it put the names out for public consultation, Grant said, and a majority of the people who weighed in said they preferred the dual-name approach. In October 2013, he said, the names were entered into the New Zealand Gazette, finally making them official.

Themes in New Zealand History

New Zealand is relatively young as a country and was one of the last places to be inhabited by humans. The first people didn’t arrive there until about a thousand years ago. By contrast, Australia is a very ancient land. The first people arrived there 50,000 to 65,000 years ago.

New Zealand is considered a "settler colony" along with Australia, Canada, and the United States: These countries were originally colonized by the British and the indigenous peoples that lived there before the British arrived were almost completely wiped out. New Zealand was first settled by England and many New New Zealanders have of English origin. Until World War II (1939–45) a large percentage of New New Zealanders were born in New Zealand and many of the rest were immigrants from Britain.

New Zealanders have been described as warm, relaxed, unpretentious, rugged, earthy, quietly modest, independent, mellow, hospitable, generous, friendly, subtly racist and opinionated. They are known for having a "can do" spirit, a strong sense of propriety, a self-deprecating sense of humor and a clean, wholesome, green way of looking at life. New Zealanders are regarded as more conservative than Australians. They have reputation for going to bed early and walking up early (partly so they can enjoy sports and recreational activities) and living life at a pace that is a little slower and less intense than in the United States.

Until around 1990, most immigrants to New Zealand came from Europe, Australia and Pacific Islands such as Samoa and Tonga. Since 1990, most of the immigrants have come from South Africa, Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, South Korea, Japan, Malaysia and Singapore. These days the term immigrant is generally used to describe immigrants from Asia not immigrants from Britain and South Africa even though many of them arrived around the same time as the Asians.

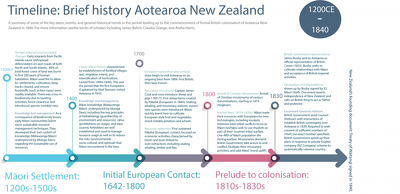

Timeline of New Zealand History

1300: Clear evidence of human habitation of New Zealand.

1642: Dutchman Tasman becomes the first known European to lay eyes on what he called "Staten Landt" later renamed "Nieuw Zeeland." After an encounter with local Maori, he sailed away.

1769: James Cook claims country for Great Britain.

1790s-1800s: Increased Maori-European (Pakeha) contacts, characterized by whaling and sealing, timber exploitation and the spread of disease. [Source: Wardlow Friesen, Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies, 2001]

1840: Treaty of Waitangi between British Crown and several important Maori chiefs cedes some political powers to British but maintains indigenous rights in perpetuity.

1860s: Land wars fought between Maori and the British administration and settlers; Maori armed resistance ends in 1872 after loss of much land.

1882: First shipment of frozen meat to England.

1907: New Zealand becomes a dominion.

1914-18: World War I; New Zealand takes over Samoa from Germany.

1935: First Labour government elected; state housing program started.

1939-45: World War II; New Zealand troops in Africa, Europe, Pacific; bulk purchases of farm produce for war effort.

1950s: Manufacturing industry expands; Maori urbanization for employment; beginning of substantial Pacific immigration.

1960s: National government in power; open access to British market for farm products.

1972-75: Labour government in power.

1975-84: National government in power; New Zealand butter quotas set by European Commission; wage and price freeze.

1984-91: Labour government undertakes economic restructuring including reduction of tariffs, abolition of subsidies to agriculture, regions etc., privatization, reduction of government services.

1987: International and New Zealand stock market crash following period of much property speculation in New Zealand.

1991-99: National coalition government in power; Employment Contracts Act introduced; welfare benefits cut; further privatization.

1999: Labour-Alliance coalition government elected on reformed policies focusing on preservation of government services, more pro-labor stance.

First People in New Zealand

The first human inhabitants of New Zealand are believed to have been Polynesians who arrived from either Tahiti, the other Society Islands or the Cook Islands. Polynesian settlers may have arrived in New Zealand in the late 1200s, with widespread settlement in the mid-1300s. They called the land Aotearoa, which legend holds is the name of the canoe that Kupe, the first Polynesian in New Zealand, used to sail to the country; the name Aotearoa is now in widespread use as the local Maori name for the country. [Source: CIA World Factbook, 2023]

The ancient Tahitian navigator named Kupe is believed to have arrived in New Zealand at present-day Te Whiti-anga-a-Kupe (meaning "Crossing Place of Kupe") on Coromandel Peninsula in the 10th century, 400 years before the Maoris and 800 years before Captain Cook. Kupe's wife reportedly named the land Aotearoa.

Sometimes referred to as "Vikings of the Sunrise," the ancient Polynesians landed on almost every habitable island in the South Pacific before A.D. 1000 and navigated an area between Southeast Asia in the west, Hawaii in the north, Easter Island to the east and New Zealand to the south. Their navigational feats far excelled those of Christopher Columbus. New Zealand was among the last places they discovered.

See Separate Article: FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

Maori

The Maori are the indigenous people of New Zealand They are of Polynesian descent. All Maoris believe they are descendants of people who arrived on seven great canoes that came from the mother island of Hawaiki in A.D. 1350. Hawaiki is most likely Tahiti or one of the Cook Islands.

According to Maori legend, New Zealand was created by the demigod Maui, who persuaded his brothers to sail to unknown waters south of their homeland on a fishing trip. Using his mother's jawbone for a hook and his own blood for bait, Maui caught a colossal fish (the North Island of New Zealand).

The Maori settled primarily on the North Island of New Zealand, which they called “Te Ika a Maui” (the Fish of Maui). The South Island is referred to as both “Te Wai Pounamu” (the Water of Jade) and Maui's canoe. The Maori ate “kumara” (a kind of sweet potato), taro, gourds, yams and rats which they brought to New Zealand from their home islands in Polynesia. They also ate moas (ostrich-size birds that are now extinct), other birds (also extinct), seals, and fish. Food was kept in bird-house-like storehouses, called “whata” or “patuka”, that were elevated on a single post.

EARLY MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

First European Explorers to Encounter New Zealand

The Dutch captain Abel Janszoon Tasman and his crew were the first Europeans to lay eyes on what is now New Zealand. They embarked from Java with two ships and orders from the Dutch East Company to find if New Guinea was attached to Australia, and in the process found New Zealand, Tasmania and Fiji. Their voyage was considered a failure because they didn't discover any ways of making money.

Tasman dropped anchor in what is now Golden Bay, a South Island inlet, in 1642 but never even made it ashore. His landing party was attacked by Maori war canoes and four Europeans were killed. After the clash, deciding it was best to leave well enough alone, Tasman left New Zealand. The place where the incident took place is also known as Murderer's Bay.

Tasman's hostile reception was the result of a misunderstanding. When his landing party approached the shores of New Zealand, the Maori welcomed them with notes from their conch shell horns. The European responded by blowing their trumpets, which was mistakenly interpreted by the Maori as a challenge and sign of aggression.

The second European encounter with New Zealand was recorded by Captain James Cook and the crew of “Endeavor”, which landed at the Coromandel Peninsula (50 miles east of present-day Auckland) in 1769. Cook arrived on Coromandel Peninsula not far from where the Tahitian navigator Kupe is believed to have landed. He named his New Zealand anchorage Mercury Bay because he fixed New Zealand's longitude on the world map by charting Mercury's transit point across the sun. He also claimed the islands for King George III, named one region the "River Thames area," and complained about sandflies in his journal.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST EUROPEAN IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, SETTLERS, SEALERS AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

First Europeans in New Zealand

After Cook, the only Europeans that ventured to New Zealand for many years were rowdy whalers and sealers and escaped convicts from New South Wales (Australia). Some of these people began settling in New Zealand beginning around 1795 mostly in transient camps and homesteads characterized by lawlessness and disorganized rules of land ownership. As a rule convicts in Australia stayed clear of New Zealand because they had been told if they went there they would be eaten by cannibals.

In the 1820s, some British ships that dropped off convicts in Sydney stopped by New Zealand on the return journey to pick up timber from massive sequoia-like kauri pines, which was used to make mats and spars for tall sailing ships. Many settlers came to New Zealand in the 1830s, 40s and 50s when there were minor gold rushes in the Auckland area, the Coromandel Mountains and the South Island. Many missionaries also arrived during those years.

After the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840 (See Below), many settlers made the 12,000-mile ocean journey from Britain to New Zealand to begin a new life. These settlers were not convicts like the early settlers of Australian but middle-class Victorian English men and women who hoped to build a well-mannered paradise in the Southern Hemisphere.

Many people from Scotland, Ireland and countries in Europe also made the trip. Some were from other British colonies. One of them, Sir Charles Eliot, a former commissioner in Kenya, called New Zealand a "a white man's country in which native questions [would] present but little interest."

In 1840, there were about 2,000 Europeans and 115,000 Maori in New Zealand. By this time the Maori were trading crops and land with the European in return for firearms, which fueled intense intertribal warfare.

See Separate Article: FIRST EUROPEAN SETTLERS IN NEW ZEALAND AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

Treaty of Waitangi

Concerned about the impact of firearms on their traditional way of life, Maori chiefs approached British government representatives in New Zealand with the idea of establishing a treaty that would stem the flow of settlers, end tribal warfare and maintain law and order. The British were anxious to make a deal as a way of preventing France or the United States from taking over New Zealand.

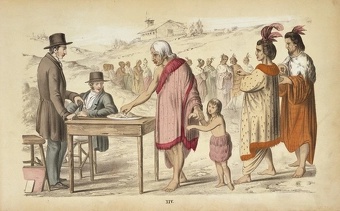

The ensuing agreement, the Treaty of Waitangi — signed on February 6, 1840 at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by representatives of the British crown and 500 Maori chiefs — promised the Maori the same rights as British subjects and protected their land and the rights of chiefs in return for giving the British crown the right to buy Maori land. There was also a clause that guaranteed Maori undisturbed ownership of their forests, fisheries, lands, and other possessions.

The treaty was signed at a time when Victorian humanitarian and the evangelical movement had a major influence on British foreign policy. It was originally intended to avoid "the disasters and the guilt of conflict with the Native Tribes," and was supposed to ensure that the Maori didn't suffer the same fate as native Americans in the United States, aborigines in Australia and Bantus in South Africa.

The British negotiated their protection in the Treaty of Waitangi, which was eventually signed by more than 500 different Maori chiefs, although many chiefs did not or were not asked to sign. In the English-language version of the treaty, the British thought the Maori ceded their land to the UK, but translations of the treaty appeared to give the British less authority, and land tenure issues stemming from the treaty are still present and being actively negotiated in New Zealand. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

Formation of New Zealand

New Zealand was given some self government and allowed to set up an elected general assembly in 1852. Dominion status was granted in 1907. In the years that followed New Zealand gradually achieved more autonomy and became so secure in its position it annexed the Cook Islands and took over German Samoa in 1914.

Independence was offered to New Zealand by Britain in 1931 in the form of the Statute of Westminster, a document which formally relinquished the powers of the British Parliament to enact laws for the dominion. The New Zealand government didn't accept the statute until 1947.

There are a lot of war memorials in New Zealand. Many of them honor New Zealander who were slaughtered alongside Australians at the Battle Gallipoli in World War I. Some 157,000 troops from New Zealand fought in World War II, including 17,000 Maori volunteers. New Zealand soldiers distinguished themselves at Tobruk and El Alamein in North Africa.

Fate of the Maori

Many Maori refused to sell their land and live under British law. These sentiments gave rise to rebellions.There were two major rebellions: one in 1860 and another from 1863 to 1881. The Maori jade clubs and spears were no match for British guns and both rebellions were put down. When the fighting was over the Maori were a defeated and largely dispossessed people.

The rebellions also resulted in mass seizures of Maori land and other injustices. By 1890, less than one sixth of New Zealand's land remained in Maori hands and a quarter of that was leased to Europeans under terms that were favorable to the Europeans.

By the turn of 20th century the Maori were almost wiped out by diseases introduced by Europeans for which they had no resistant. In 1900 there were only about 40,000 Maori, down from 200,000 in 1840. Today there numbers have rebounded to 500,000, thanks mainly to modern medicine, increased resistance to disease, a high birth rate and intermarriage.

New Zealand Considers Changing its Name to It Maori Name

In 2022, NPR reported: As the people of New Zealand confront their nation's troubled past with colonization and denying the Maori people rights, a name change for the island nation is being considered as a part of its own reckoning. A petition that aims to change the Dutch anglicized name of New Zealand to its indigenous Maori designation of Aotearoa has collected more than 70,000 signatures, prompting a parliamentary committee to consider the idea. [Source: Ailsa Chang, NPR, August 5, 2022]

New Zealand member of parliament Debbie Ngarewa-Packer , co-leader of The Maori Party, told NPR’s All Things Considered; The name change would be “indicative or prescriptive of the long white cloud of the island as it's depicted often, and the weather that we have down at the end of the world. But most importantly, it reflects indigenously who we are, and that we are, in fact, in the Pacific, that we are an island nation, and we're not in any way connected to the origins of New Zealand.

On why it is important for the Maori Party to push for a formal name change, she said: It's really important that we dismantle some of the grips of colonization that have hindered our ability to reach our true potential. And one of the biggest things that's reflected in some of the poorer states across the nation is the lack of self-identity, is the lack of actually understanding even who the tangata whenuaor Indigenous people, Maori of Aotearoa are.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025