Home | Category: History / History and Religion / History and Exploration

COOK’S VOYAGES

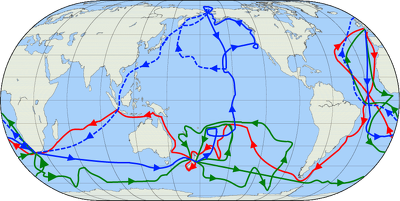

Three voyages of Captain James Cook, with the first in red, second in green, and third in blue; the route of Cook's crew following his death is indicated with dashed blue line

Captain James Cook made three major voyages in the Pacific

First voyage (1768–1771)

Second voyage (1772–1775)

Third voyage (1776–1779)

Cook and his crew recorded in great detail the people of the areas that they visited — their appearance, dress, language, customs, beliefs and activities.

In these voyages, Cook sailed thousands of miles across largely uncharted areas of the globe. He mapped lands from New Zealand to Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean in greater detail and on a scale not previously charted by Western explorers. He surveyed and named features, and recorded islands and coastlines on European maps for the first time. He displayed a combination of seamanship, superior surveying and cartographic skills, physical courage, and an ability to lead men in adverse conditions.

Terence E. Hays wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The list of islands and island groups 'discovered" or "rediscovered" by Cook is long, induding the Hawaiian group, Christmas Island, New Caledonia, the Cook Islands, the Gilbert Islands, Fiji, Tonga, the Solomon Islands, Easter Island, and part of the Tuamotu Archipelago. In addition, his carefully drawn charts proved finally that New Guinea, New Zealand, and Australia were not joined together, as many had supposed. Cook's accomplishments, including a vast quantity of scientific specimens and observations, have never been equaled, in the Pacific or elsewhere in the world. By the conclusion of Cook's voyages, the main outlines of the island groups of Oceania were charted, and only locally systematic exploration would be undertaken in the future. From the Europeans' point of view, now was the time for exploitation of the resources and people of this vast new realm. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

Related Articles:

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN THE PACIFIC: DESCRIPTIONS, EVENTS AND PLACES VISITED ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND: EXPLORERS, TASMAN, COOK, SEALERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST EUROPEAN SETTLERS IN NEW ZEALAND AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

EUROPEANS IN THE PACIFIC IN THE 1800S: WHALERS, MISSIONARIES, COPRA AND FORCED LABOR ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com ;

EUROPEANS DISCOVER THE PACIFIC AND OCEANIA ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

MAGELLAN AND THE FIRST VOYAGE AROUND THE WORLD ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA BY EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Mission of Cook’s Voyages

The goal of Captain James Cook's voyage around the world was to improve navigation and search for the great mythical southern continent of terra australis incognita, an unknown "south land". On June 3, 1769 the planet Venus crossed the path of the sun, an event that only happens once a century. By calculating when this moment occurred from different points around the world the distance from the earth to the sun could be calculated. One of the reason's for Captain Cook's first expedition was to make Venus calculations from Tahiti.

Cook had explicit instruction to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives” with the aim of expanding British trade. Cook is sometimes refereed to as the "world's greatest negative explorer." By meticulously covering the South Pacific in an organized grid-like pattern he proved within a reasonable doubt that the Great Southern continent did not exist. In the process he almost discovered Antarctica by passing within 70 miles of the continent's coast. Icebergs prevented him from venturing closer.≈

Tony Horwitz wrote in “Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before:” Though Ferdinand Magellan had first crossed the Pacific two and a half centuries before, the ocean-covering an area greater than all the world's landmasses combined-remained so mysterious that mapmakers labeled vast stretches of the Pacific nondum cognita (not yet known). Cartographers knew so little of the lands within the Pacific that they simply guessed at the contours of coasts: a French chart from 1753, fifteen years before the Endeavour's departure, shows dotted shorelines accompanied by the words "Je suppose." [Source: Tony Horwitz “Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before” (Picador USA, 2003]

But the most persistent and alluring mirage of Pacific exploration was terra australis incognita, an unknown "south land," first conjured into being by the wonderfully named Roman mapmaker Pomponius Mela. He, like Ptolemy, believed that the continents of the northern hemisphere must be balanced by an equally large landmass at the bottom of the globe. Otherwise, the world would tilt. This appealingly symmetrical notion was embellished by Marco Polo, who claimed he'd seen a south land called Locac, filled with gold and game and elephants and idolators, "a very wild region, visited by few people." Renaissance mapmakers took the Venetian's vague coordinates and placed Locac-also known as Lucach, Maletur, and Beach-far to the south, part of the fabled terra australis. The discovery of America only heightened Europeans' conviction that another vast continent, rich in resources, remained to be found.

So things stood in 1768, when London's august scientific group, the Royal Society, petitioned King George III to send a ship to the South Pacific. A rare astronomical event, the transit of Venus across the sun, was due to occur on June 3, 1769, and not again for 105 years. The society hoped that an accurate observation of the transit, from disparate points on the globe, would enable astronomers to calculate the earth's distance from the sun, part of the complex task of mapping the solar system. Half a century after Isaac Newton and almost three centuries after Christopher Columbus, basic questions of where things were-in the sky, as well as on earth-remained unresolved.

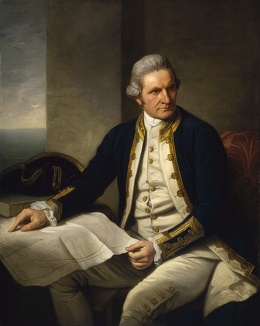

The king accepted the society's request, and ordered the Admiralty to fit out an appropriate ship. As commander, the Royal Society recommended Alexander Dalrymple, a distinguished theorist and cartographer who had sailed to the East Indies, and who believed so firmly in the southern continent that he put its breadth at exactly 5,323 miles and its population at fifty million. The Admiralty instead selected James Cook, a Navy officer whose oceangoing experience was limited to the North Atlantic. On the face of it, this seemed an unlikely choice-and, among some in the establishment, it was unpopular. Cook was a virtual unknown outside Navy circles and a curiosity within. He had spent the previous decade charting the coast of Canada, a task at which he displayed exceptional talent. One admiral, noting "Mr. Cook's Genius and Capacity," observed of his charts: "They may be the means of directing many in the right way, but cannot mislead any."

Backdrop of Cook’s Voyages

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Power struggles in Europe in the eighteenth century resulted in significant new presences in Oceania. Occasional Dutch explorers still made new 'discoveries," such as Jacob Roggeveen, who sighted Samoa and Easter Island in 1722, but it was the French and English ship captains who came to dominate the Pacific in the 1700s. Some were buccaneers, preying on the Spanish galleons that by then regularly sailed between the Philippines and South America, but others were in search of colonies or scientific knowledge. French navigators such as Philip Carteret and Louis Antoine de Bougainville explored the Solomon Islands, and the Englishman Samuel Wallis visited the Marshall Islands, Tahiti, and other parts of Micronesia and Polynesia. But the major European figure in the Pacific from 1768 to 1779 was the great British navigator Captain James Cook. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

Tony Horwitz wrote: One reason for” the ignorance about the Pacific Ocean “was that most of the ships sailing after Magellan followed the same, relatively narrow band of ocean, channeled by prevailing winds and currents, and constrained by poor navigational tools. Also, geography in the early modern era was regarded as proprietary information; navies kept explorers' charts and journals under wraps, lest competing nations use them to expand their own empires. [Source: Tony Horwitz “Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before” (Picador USA, 2003]

Not that these reports were very reliable. Magellan's pilot miscalculated the longitude of the Philippines by 53 degrees, an error akin to planting Bolivia in central Africa. When another Spanish expedition stumbled on an island chain in the western Pacific in 1567, the captain believed he'd found the biblical land of Ophir, from which King Solomon shipped gold, sandalwood, and precious stones. Spanish charts, and the navigational skills of those who followed, were so faulty that Europeans failed to find the Solomon Islands again for two centuries. No gold and not much of economic value was ever discovered there.

Pacific adventurers also showed an unfortunate tendency toward abbreviated careers. Vasco Nzqez de Balboa, the first European to sight the ocean, in 1513, was beheaded for treason. Magellan set off in 1519 with five ships and 237 men; only one ship and eighteen men made it home three years later, and Magellan was not present, having been speared in the Philippines. Francis Drake, the first English circumnavigator, died at sea of dysentery. Vitus Bering, sailing for the czar, perished from exposure after shipwrecking near the frigid sea now named for him; at the last, Bering lay half-buried in sand, to keep warm, while Arctic foxes gnawed at his sick and dying men.

“Endeavour off the coast of New Holland during Cook's voyage of discovery 1768-1771", a painting by Samuel Atkins (1787-1808); an inscription on reverse of painting indicates it relates to the grounding of the Endeavour on the Great Barrier Reef in June 1770

Other explorers simply vanished. Or went mad. In 1606, the navigator Fernandes de Queirss told his pilot, "Put the ships' heads where they like, for God will guide them as may be right." When God delivered the Spanish ships to the shore of what became the New Hebrides, Fernandes de Queirss founded a city called New Jerusalem and anointed his sailors "Knights of the Holy Ghost."

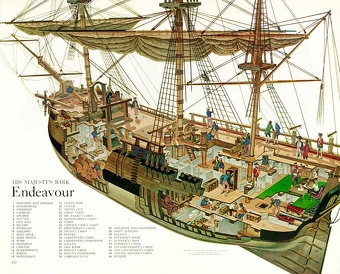

Cook's Ship, Endeavour

“Endeavour”, Cook's ship on his first voyage, was a flat-bottomed bark that weighed 334 tonnes (368 US tons) and was 30 meters (98 feet) long and 8.5 meters (29 feet) wide. A converted coal carrier, it was a slow, thick-hulled ship that had a huge storage capacity for boat of such a small size. It was also easy to beach and repair because it didn't have a projecting keel, and the hull were packed closely together with flathead nails to deter wood-boring shipworms.

Horwitz wrote: Among other things, I learned that the original Endeavour was a mirror of the man who commanded it: plain, utilitarian, indomitable. Like Cook, the ship began its career in the coal trade, shuttling between the mine country of the north of England and the docks of east London. Bluff-bowed and wide-beamed, the ship was built for bulk and endurance rather than speed or comfort. "A cross between a Dutch clog and a coffin," was how one historian described it. [Source: Tony Horwitz “Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before” (Picador USA, 2003]

The tallest of the Endeavour's three masts teetered a vertiginous 127 feet. Belowdecks, the head clearance stooped to four foot six. The Endeavour's flat bottom and very shallow keel-designed so the collier could float ashore with the tide to load and unload coal-made the ship exceptionally "tender," meaning it tended to roll from side to side. "Found the ship to be but a heavy sailer," wrote the ship's botanist, Joseph Banks, "more calculated for stowage, than for sailing." He wrote this in calm seas, two days after leaving England. When the going turned rough, Banks retreated to his cot, "ill with sickness at stomach and most violent headach."

Life of the Crew of the Endeavour

The Endeavour carried 94 men. Sailors on the original ship wore no prescribed uniform, In Cook's day," says historian Allan Villiers, "merchant seamen were press-ganged into navy ships as needed — waylaid in seaports, slugged, drugged, or dragged aboard."

"Slops" was the eighteenth-century term for naval gear. On his experience on a replica of the Endeavour, Horwitz We went “across the ship's deck and down a ladder, or companionway, which plunged to a dark chamber called the mess deck. We squinted at tables roped to the ceiling, as well as vinegar kegs, a huge iron stove, and sea chests that doubled as benches-all packed into a room the size of a suburban den. This cramped cavern would somehow accommodate thirty of us, with the other ten recruits in a small adjoining space. [Source: Tony Horwitz “Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before” (Picador USA, 2003]

We were tossed canvas hammocks and were showed how to lash them to the beams above the tables. We were allotted just fourteen inches' width of airspace per sling, the Navy's prescribed sleeping area in the eighteenth century. "If you don't know knots, tie lots," as I struggled to complete a simple hitch. He also showed us how to stow the hammocks, snug and tightly roped, in a netted hold.

Stumbling around the dark deck, colliding with tables and people, and bending almost double when the head clearance plunged to dwarf height, I tried to imagine spending three years in this claustrophobic hole, as Cook's men had. Incredibly, the original Endeavour left port with forty more people than we had on board-accompanied by seventeen sheep, several dozen ducks and chickens, four pigs, three cats (to catch rats), and a milk goat that had circled the globe once before. "Being in a ship is being in a jail," Samuel Johnson sagely observed, "with the chance of being drowned."

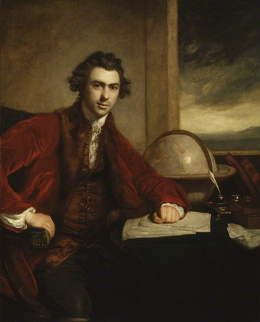

Joseph Banks

With Cook on the Endeavour was the famous botanist Joseph Bank (1743-1820), a blue-blooded nobleman who was accompanied by two footmen and two black servants from his estate as well as two greyhounds and chemicals for storing specimens. His entourage also included his friend Daniel Solander, two artists, and a secretary. The footmen and servants also helped as assistant collectors and a large section of storage hold of the “Endeavour” was occupied by Banks possessions and natural history library. [Source: T.H. Watkins, National Geographic, November 1996]

Banks used his immense fortune to help fiance Cook's first expedition but was not invited on the Cook's second voyage because his demands (including on board musicians) were too much for the expedition to the meet. Banks was a confidant of crazy King George III, He was educated at Harrow, Eton and Oxford, and inherited 10,000 acres of land in several estates at the age of 21 and became one of the wealthiest men in England.

Banks had been interested in nature since he was a child. He liked to pet toads in front of people and explain how they were beneficial to humankind because they ate pests. He began his first plant collection at Eton, where he taught himself botany. At Oxford he was a leading members of the Botanical Club, Fossil Club and the Antiquarian Club. When Banks asked when he was going to do his Grand Tour of Europe, which was the custom of men in his class, he responded, "Every blockhead does that. My grand tour shall be one round the whole globe."

One of Banks's colleagues at the Royal Society wrote: "No people ever went to sea better fitted out for the purpose of Natural History, nor more elegantly...they have all sorts of machines for catching and preserving insects; all kinds of nets, trawls, drags, and hooks for coral fishing...They have many cases of bottles with ground stoppers, of several sizes, to preserve animals in spirits...In short. Solander assured me this expedition would not cost Mr. banks ten thousand pounds."

Impact of Joseph Banks

Banks expanded the Western world' knowledge of plants by 25 percent. He described banana and breadfruit trees, palm-like pandanus, hibiscus wild ginger, morning glory and some 30,000 kinds of plants and animals. Some the nearly 5,000 insect specimens collected by Banks and now housed at the Natural History Museum in London have to be identified. After returning from the Endeavour Banks went on the longest serving president of the Royal Society of London, the most prestigious group of scientist in his time, and held a position held for decades by Sir Isaac Newton. He also became director of the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, which he wanted to transform into the greatest botanical garden in the world. The number of species grew from 3,400 to 11,000 under banks stewardship.

Old man banksia (Banksia serrata) specimen alongside an illustration by Sydney Parkinson; Banks brought thousands of new species to the attention of Western science, including acacia, eucalyptus and banksia, a genus named in his honor

It was Bank's idea to colonize Australia with convicts. Banks also ordered Captain William Bligh to gather breadfruit in Tahiti and ship to the Carribean, an event that triggered the famous “Mutiny on the Bounty.” Banks was also instrumental in growing Chinese tea in India. Banks also joined Samuel Johnson's Literary Club, fathered an illegitimate child and took a mistress until his marriage in March 1779 to Dorthea Hugessen who Solander described as "rather handsome, very agreeable, chatty & laughs a good deal.

Bank's plan to introduce hearty, filling and nutritious breadfruit to the Caribbean as a food source for African slaves failed when the slaves refused to eat it because it didn't have any taste. The fruit was delivered by Captain Bligh. The eminent Harvard biologist, E.O. Wilson, once said "If I could be any person from the past it would be Joseph Banks. Banks died of gout at te age of 77 in 1820.

Artists also sailed on Cook's first voyage. Sydney Parkinson was heavily involved in documenting the botanists' findings, completing 264 drawings before his death near the end of the voyage. They were of immense scientific value to British botanists. Cook's second expedition included William Hodges, who produced notable landscape paintings of Tahiti, Easter Island, and other locations.

First Voyage of Captain Cook (1768–1771)

Cook's first expedition — from September 1768 to July 1771 — began in England (September 1768) and then went to Rio de Janeiro (November 1768), Terra del Fuego (January 1769), Tahiti (March 1769), New Zealand (October 1769), Australia (early 1770), Jakarta (late 1770), South Africa (March 1771) and England (July 1771).

Terence E. Hays wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Cook's first voyage was undertaken primarily for scientific knowledge (although British colonial ambitions were a significant factor as well). He was commissioned to observe the transit of Venus before the sun, with Tahiti identified as the best location for the necessary astronomical measurements, and to find Terra Australis. He returned with detailed charts and new information regarding Tahiti and New Zealand, as well as other islands, but no news of a southern continent. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

In May 1768, the Admiralty commissioned Cook to command a scientific voyage to the Pacific Ocean. Cook, at age 39, was promoted to lieutenant to grant him sufficient status to take the command. For its part, the Royal Society agreed that Cook would receive a one hundred guinea gratuity in addition to his Naval pay. After departing England, Cook and his crew rounded Cape Horn and continued westward across the Pacific, arriving at Tahiti, where the observations of the transit were made. However, the result of the observations was not as conclusive or accurate as had been hoped. Once the observations were completed, Cook opened the sealed orders, which were additional instructions from the Admiralty for the second part of his voyage: to search the south Pacific for signs of the postulated rich southern continent of Terra Australis. [Source: Wikipedia]

On the people of Tierra del Fuego, Cook wrote in his journal: “the women…seldom exceeding 5 ft …In this dress there is no distinction between men and woemen, except that the latter have their cloak tied round their middle with a kind of belt or thong and a small flap of leather hanging like Eve’s fig leaf over those parts which nature teaches them to hide… Their food…was either Seals or shell fish…the latter were collected by the woemen, whose business it seemed to be to attend at low water with a basket in one hand, a stick with a point and barb in the other, and a satchel on their backs which they filled with shell fish.” The men “are something above the Middle size of a dark copper Colour with long black hair, they paint their bodies in Streakes mostly Red and Black, their cloathing consists wholly of a Guanoacoes (llama-like animals) skin or that of a Seal, in the same form as it came from the Animals back, the Women wear a peice of skin over their privey parts but the Men observe no such decency.”[Source: Cook, Journal I, 227-8, 20 January and p.44, 16th January 1769]

After leaving Australia, the “Endeavour” stopped in the Dutch port Jakarta, where the majority of the members of the expedition became sick with dysentery and typhus. When the ship arrived in England in July 1771 only 41 or the original 94 crew members were still alive. To reach England the Endeavour rounded the Cape of Good Hope in Souther Africa and stopping at the island of Saint Helena. Cook's journals were published upon his return, and he became something of a hero among the scientific community. Among the general public, however, Banks was a greater hero.

Second Voyage of Captain Cook (1772–1775)

Cook's second voyage was over three years long — from July 1772 to July 1775. He left Plymouth in two Whitby collier-barks. The purpose was to look for the rumored southern continent. He covered almost the whole of the Pacific, including islands off the the coast of Antarctica, and established that Australia was large, but not the continent that had been imagined, and that Terra Australis was only imaginary. Banks had attempted to take command of Cook's second voyage but removed himself from the voyage before it began, and Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg Forster were taken on as scientists for the voyage. Cook's son George was born five days before he left for his second voyage. On the second voyage only four men died in the three-year 110,000-kilometer (70,000-mile) journey.

Cook commanded HMS Resolution on this voyage, while Tobias Furneaux commanded its companion ship, HMS Adventure. Cook's expedition circumnavigated the globe at an extreme southern latitude, becoming one of the first ship to cross the Antarctic Circle. In the Antarctic fog, Resolution and Adventure became separated. Furneaux made his way to New Zealand, where he lost some of his men during an encounter with Māori, and eventually sailed back to Britain, while Cook continued to explore the Antarctic and almost encountered the mainland of Antarctica but turned towards Tahiti to resupply his ship. He then resumed his southward course in a second fruitless attempt to find the supposed continent.

Before returning to England, Cook made a final sweep across the South Atlantic from Cape Horn and surveyed, mapped, and took possession for Britain of South Georgia, which he named after King George III. It had been explored by the English merchant Anthony de la Roché in 1675. Cook also discovered and named Clerke Rocks and the South Sandwich Islands ("Sandwich Land"). He then turned north to South Africa and from there continued back to England. His reports upon his return home put to rest the popular myth of Terra Australis.

Cook's second voyage marked a successful employment of Larcum Kendall's K1 copy of John Harrison's H4 marine chronometer, which enabled Cook to calculate his longitudinal position with much greater accuracy. Cook's log was full of praise for this time-piece which he used to make charts of the southern Pacific Ocean that were so remarkably accurate that copies of them were still in use in the mid-20th century.

Upon his return, Cook was promoted to the rank of post-captain and given an honorary retirement from the Royal Navy, with a posting as an officer of the Greenwich Hospital. He reluctantly accepted, insisting that he be allowed to quit the post if an opportunity for active duty should arise. His fame grew. He dined with James Boswell; he was described in the House of Lords as "the first navigator in Europe". But he yearned by to back at sea.

Cook and Antarctica

Cook became one of the first people to cross the Antarctic Circle — on in January 1773. He sailed within 200 kilometers (125 miles) of the Antarctic coast but failed to find the continent. He went south of the Antarctic Circle twice. Once south of South Africa and a second time south of new Zealand. Both times was forced to turn back because the danger presented by large icebergs."

In the Antarctic fog south of New Zealand, Resolution and Adventure became separated. Furneaux made his way to New Zealand, where he lost some of his men during an encounter with Māori, and eventually sailed back to Britain, while Cook continued to explore the Antarctic. He made as far south as 71°10'S — on 31 January 1774.

Cook later wrote: "I had now made the circuit of the Southern Ocean...in such a manner as to leave not the least room for the Possibility of there being a continent unless near the Pole and out of reach of Navigation." The continent was finally sighted by U.S., British and Russian vessels in 1820. Intense explorations of Antarctica began in the 1890s.

Third Voyage of Captain Cook (1776–1779)

Not so long after the second voyage was completed, Cook volunteered to find the Northwest Passage and a third voyage commenced. He ventured to the Pacific once again, this time hoping to travel east to the Atlantic, while another expedition traveled from Atlantic to the Pacific. During this trip rip Cook was killed in Hawaii. The third voyage, which was completed after Cook's death, lasted four years and three months — from July 1776 to October 1780 — was one of the longest voyages of discovery in history. [Source: "The Voyages of Captain Cook" by Alam Villiers, September 1971]

On his final voyage the illusory goal the 'Northwest Passage" — a waterway north of what is now that would connect the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. He looked for an eastward entrance for the Northwest Passage by sailing through the Bering Strait. He also found the Hawaiian Islands (which he named the Sandwich Islands after his friend and patron, the Fourth Earl of Sandwich), where he was killed by native Hawaiians in 1779.

On his last voyage, Cook again commanded HMS Resolution, while Captain Charles Clerke commanded HMS Discovery. The public was told that the voyage was planned to return the Pacific Islander Omai to Tahiti, its primary goal was to locate a Northwest Passage, After dropping Omai at Tahiti,Cook travelled north and in 1778 became the first European to begin formal contact with the Hawaiian Islands. [Source: Wikipedia]

From the Sandwich Islands, Cook sailed north and then northeast to explore the west coast of North America north of the Spanish settlements in Alta California. He sighted the Oregon coast and spent some time in the Nootka Sound off Vancouver Island, trading with local ethnic groups. After leaving Nootka Sound in search of the Northwest Passage, Cook explored and mapped the coast all the way to the Bering Strait, charting the majority of the North American northwest coastline on world maps for the first time, determining the extent of Alaska, and exploring the region between in Russian control to west and Spanish control to the south.

Describing the people in this area, Cook wrote: “I saw not a woman with a head dress of any kind, they had all long black hair a part of which was tied up in a bunch over the forehead….though the lips of all were not slit, yet all were bored, especially the women and even the young girls; to these holes and slits they fix pieces of bone of this size and shape, placed side by side in the inside of the lip; a thread is run through them to keep them together…This Ornament is a very great impediment to the Speech.” [Source: Cook, Journals III, I, 350]

In June 1778 a young Aleut native, Yermusk, was taken aboard the Resolution after his canoe capsized. On the people in the Aleutians, Cook wrote in his journal: “These people are rather low of Stature, but plump and well shaped, with rather short necks, swarthy chubby faces, black eyes, small beards, and straight long black hair…Their dress…both, Man and Womens are made alike, the only difference is in the Materials, the Womans frock is made of Seal skin and the Mens of birds skin and both reach below the knee…some of them wear boots and all of them a kind of oval snouted Cap made of Wood with a rim to admet the head” [Source: Cook, Journals III, I, 459-60)

On the people in Alaska, Samwell wrote: “We met several Indians…a very beautiful young Woman accompanied by her Husband…Mr.Webber was willing to have a sketch of her, and as we had time enough on our Hands we sat down together and he made a drawing of her; we were all charmed with the good nature & affability with which she complied with our Whishes in staying to have her picture drawn….She was withal very communicative & intelligent & its was from her I learnt that the Name of the Harbour where the Ships lie is Samgoonoodha.” [Source: Cook, Journals III, 2, 1124]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Source: National Geographic article by Alan Villiers; the book "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2025