MĀORI CUSTOMS

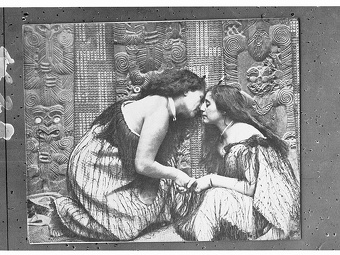

The traditional Māori greeting is called a “hongi”. It involves a hand shake and a nose press in which two people press their nose together, close their eyes and go "mm-m." Men and women, women and women and men and men greet each other using the “hongi”. It is believed that their spirits mingle when doing this. The hongi is an ancient custom linked to the story of Tāne Mahuta, who formed the first woman, Hineahuone, from the earth and breathed life into her through her nose. This act is recalled whenever people greet each other with a hongi. Many Māori, Pacific Islanders and Inuits (Eskimos) prefer to rub noses rather than kiss. During the SARS and Covid-19 outbreaks, Māori were warned against performing their customary nose-rubbing greeting.

Māori today, like other New Zealanders, typically address each other informally and emphasize friendliness in relationships. Māori customs — practices before the Māori came into contact with other cultures — were taken less seriously by the 1990s. Some Māori don't like to have their picture taken. If you want to take some pictures or Māori ask for permission first. [Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999 /=]

Hakari (feasting) is and has been an important component of Māori culture. Māori feasts traditionally brought together a number of different families and other social groups and have been hosted by a man of status, who provided food and gifts for those who attended and was left broke in the end but with a higher level of status. These days it is customary for Hakari participants to donate some money when they join the event to help defer the costs.

According to “CultureShock! New Zealand”: If you are invited to a Māori function, say a wedding or a funeral (tangi), you will be welcomed to the marae (traditional meeting house) in a group. You will therefore assemble outside with the other guests and wait to be conducted in. During the welcome, the visiting group of which you are a member, will present the koha, which is usually money, to help the hosts with the expenses associated with the hosting. While waiting outside, you will see someone going around with an envelope and he (it is usually a man) will take your contribution and later present it, together with the others, to the hosts. If you are unsure about how much to contribute, a discreet inquiry to one of the other guests will solve the problem and save anxiety.

Some customs have been adapted to non-traditional situations. For instance, many marae (sacred areas) in cities or outside New Zealand are multi-tribal, so tribal traditions have to be adapted. Māori ceremonies are also used in non-Māori settings, such as the opening of the Te Māori exhibition in New York in 1984. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN THE PACIFIC REGION, POLYNESIA AND MELANESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

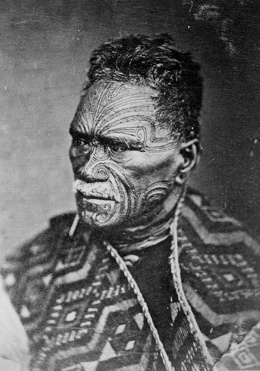

MĀORI TATTOOS: HISTORY, HOW THEY WERE MADE, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WAKA (MĀORI CANOES): HISTORY, TYPES, ART, HOW THEY ARE MADE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Māori-Related Tourism

The Māori make up about 18 percent of the population of New Zealand. The vast majority (86 percent) of present-day Māori live on the North Island. Most Māori live on the northern half of the North Island, particularly around Rotorua, Taupo, Waikato, Northland, East Cape, Taranaki and Wanganui. Many New Zealand cities, especially Auckland, have large Māori populations.

The main center of Māori tourism is Rotorua and the main Māori places there are Te Puia and Whakarewarewa Living Māori Village. But these places are not the only places in Rotorua or New Zealand as a whole (See Below). The Northland is where a lot of Māori-majority towns are. The 96-page book— The Rough Guide to Māori New Zealand: Discover the Land and People of Aotearoa — was published in 2005 and is now out of print but you can buy it used at Amazon.com. New Zealand Geographic did a fairly lengthy article about Māori tourism at nzgeo.com .

Māori Tourism Centers and Agencies

1) New Zealand Māori Tourism Council (NZMTC)

www.Māoritourism.co.nz

Porirua, New Zealand

2) Tourism New Zealand (TNZ)

https://www.tourismnewzealand.com

Māori Tourism in Northland

Taiamai Tours Heritage Journeys, Te Karuwha Parade, Paihia,

Tu Tika Tours, 92 Otaika Road, Raumanga, Whangārei 0110,

Te Ara Tours, 50 Seabreeze Rd, Mangawhai Heads, Mangawhai,

Te Ahu Centre, Kaitaia

Māori Cultural Centre. Kaitaia

Waitangi Treaty Grounds, Tau Henare Drive, Waitangi 0293,

Ngāpuhi cultural experiences, Paihua

Māori Tourism Agencies in Businesses Auckland

Kiko Guided Tours, 4 Feltwell Place, Māngere, Auckland

TIME Unlimited Tours, 92 Franklin Road, Freemans Bay, Auckland 1011

Navigator Tours, Waterfront Road, Māngere Bridge, Auckland 2022

The Exquisite Group, 2A Fernwood Place, Wai O Taiki Bay, Auckland 1072,

Māori Tourism in Rotorura and the Bay of Plenty

Māori Culture Tours, Bay of Plenty NZ, https://www.bayofplentynz.com

RotoruaNZ, https://www.rotoruanz.com

Te Pā Tū, 1072 State Highway 5, Rotorua, Bay of Plenty

Whakarewarewa – The Living Māori Village, 17 Tyron Street, Rotorua, Bay of Plenty

Mitai Māori Village, 196 Fairy Springs Road, Rotorua, Bay of Plenty

Kohutapu Lodge & Tribal Tours, 3836 Galatea Road Galatea, Murupara

Tāpoi Travel, PO Box 239 Te Puke, Bay of Plenty

Basic Māori Rules and Taboos

Basic Māori household and social rules:

1) Remove your shoes before entering a home or marae (sacred area with a meeting house).

2) Don't touch another person’s head, unless a Māori person says okay. For Māori, the head is tapu (sacred).

3) Don't step over people when you're trying to find a spot to sit. Ask the person to move their legs first, or find another path. In Māori culture, it's considered rude for a woman to step over a man.

4) You should not sit on pillows or cushions, but using them to prop up your back is fine.

5) Don't enter or cross a room while someone in authority is addressing an audience. Wait quietly by the door until there's a break in the dialogue or, crouch down as you pass as a sign of respect. Māori society is hierarchical and crossing in front of a more ‘senior’ person is considered rude. [Source: New Zealand government]

Tapu is a Māori and Polynesian word that is the source of the word “taboo.” Tapu can refer to a state of sacredness, spiritual restriction, or an implied prohibition. The crossing of the sacred (tapu) and the unsacred (noa) realms is restricted. The head is considered the most sacred part of the body, so it is taboo to touch another person's head without permission. Noa represents something unsacred or ordinary, and the concept helps explain why food is kept separate from sacred spaces and objects. Food is generally considered noa (unsacred), while many places and objects, like a marae, are tapu (sacred). Food should never be taken into a carved meeting house.

Māori taboos restrict interactions with sacred things and places. Common ones as eluded to before include removing shoes before entering sacred spaces like a marae or cemetery, never putting your feet on food tables, and not passing food over someone's head. Also, don't shout near the ocean, always put a rock back where you found it and don't eat below the tide line. There is a practical side to these taboos. For example you don't eat below the tide line because food left behind may attract sharks. Māori have traditionally ostracized people who handled corpses and in some circles commercialism is regarded as profane. A rāhui was a restriction placed on a place or resource to make it tapu and prevent access. Rāhui were often imposed after a death — for instance, if someone drowned, a rangatira or tohunga might place a rāhui over the waterway to prohibit use for a set period.

There have been a number of rituals performed to remove tapu and render a person or object noa (free from its restrictions). Whakahoro was a ceremony that used water to cleanse people of tapu. Another ritual, hurihanga takapau (turning the mat), was performed to lift tapu. It was famously used by Māui to remove the tapu from the North Island (“his great fish”).Ngau paepae was a ritual that could both increase the tapu of warriors preparing for battle and neutralise certain kinds of tapu. The name means “biting the beam between the two posts of a latrine.” Anthropologists Allan and Louise Hanson, after examining early manuscripts describing this practice, concluded that the gods did not avoid the latrine as humans did. When Rupe visited the home of the god Rehua, excrement was present, suggesting it was not noa. Thus, biting the latrine beam symbolically connected the participants to the divine realm, either drawing tapu from it or returning tapu to it. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Māori Eating Customs

Māori eating customs emphasize community and respect, with meals often starting with a spiritual blessing (karakia) and guests waiting for elders to begin eating. Traditional practices include community-prepared meals in a communal dining hall (wharekai) and hygiene practices like washing hands before eating. Visitors are expected to thank hosts and sometimes sing songs as a show of gratitude for their hospitality.

Communal meals are common, and visitors are encouraged to interact and mingle with the hosts during the meal. Māori groups such as families and subclans have traditionally seen as groups that ate together. Meals are often served in a wharekai (dining room), a space separate from the main meeting house. Community members often cook and serve meals voluntarily, so showing appreciation for their work is important.

Basic Māori eating customs:

1) Don't put hats on food tables. Remember, heads are tapu so anything that relates to heads, like pillows or hats, are treated carefully.

2) Don't pass food over anybody’s head. It's common for Māori to share food to welcome people, celebrate success or build community, but it needs to be handled carefully.

3) Don't sit on tables, especially tables with food on them. Putting your bottom or bag on the table is seen as unclean. [Source: New Zealand government]

It is a good idea for people to wash their hands before eating as a nod to good hygiene. Elders (kaumātua) and children are often served or allowed to begin eating first. There is an expectation to finish all the food on your plate, or other family members will help, to avoid waste. It is customary for guests to thank their hosts, especially towards the end of the meal, to acknowledge the hospitality and effort put into the meal.

Peter Oettli wrote in “CultureShock! New Zealand”: “ It is customary for a senior member of the group to say grace before the meal. This is generally said in Māori and you should not start to eat before the karakia has been said. Also, Māori find it most offensive if you sit on a table where food has been served or may be served later. The best thing to do is simply never to sit on a table in a Māori setting.

See Hangi — the Māori Feast Under MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES, TATTOOS, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Māori Ceremonies, Rituals and Chants

Karakia were a form of communication with the gods, similar to prayers or chants. Tohunga (priests) were regarded as the most appropriate people to perform them, as they acted as intermediaries between humans and the spiritual world. However, karakia were used by everyone — children and adults alike. Adults might use a short chant to repel unseen forces, such as “Kuruki, whakataha!” (“Lose power, pass aside!”). Children had their own karakia tamariki, such as chants to stop the rain. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

Different types of karakia served specific purposes. Kī tao empowered weapons for battle, Tā Kopito was used for healing sickness, Tūā moe was recited by bird catchers to lull the tūī to sleep, Tūā mana was used to ease childbirth, and Hoa Tapuae was a set of karakia chanted by warriors to increase speed. Scholar Te Rangi Hīroa (Peter Buck) described ritual as “the form of conducting the whole rite relating to one subject,” encompassing both ceremonial actions and the chanting of appropriate karakia.

Most activities related to cultivating or gathering food were under the guardianship of specific atua (deities). The first fruits of any harvest or catch were always offered to the relevant atua. For example, Rongo, the god of cultivated foods, received the first kūmara harvested, which were planted in a special garden known as a māra tautāne.

The ritual whāngai hau involved offering food to an atua, symbolically feeding (whāngai) the spiritual essence (hau) of the offering. Fishermen would return their first catch to Tangaroa, god of the sea. In one tradition, Manuruhi, the son of Ruatepupuke, failed to perform the karakia and offer the first fish to Tangaroa. In anger, Tangaroa dragged him beneath the sea and transformed him into a tekoteko (carved figure) on his wharenui. Similarly, bird catchers offered their first catch to Tāne, god of the forest, and Tūmatauenga, god of war, received te mata-ika (“the face of the fish”), the first man slain in battle.

Ceremonies for Children: Traditionally, when a baby has been born, Māori have buried the whenua (placenta) on land associated with one or both parents. Some Pākehā now follow this custom as well. Mostly in the past, after a baby’s tāngaengae (navel cord) was cut, the Tūā ceremony was held at the birthplace. It removed tapu from both mother and child and ensured the child’s health. The Tohi rite followed the tūā. Performed at a sacred stream, it dedicated the child to a particular god — boys were often dedicated to Tūmatauenga (god of war) and girls to Hineteiwaiwa (goddess of childbirth and weaving). The Pure ceremony came after the tohi, making the child’s spiritual power (mana) permanent. Adults who had taken part then underwent whakanoa, the removal of tapu, either near the turuma (latrine) or at a stream.

Powhiri

A powhiri (spelled pohiri in eastern dialects and pronounced PAW-feer-ee or POH-feer-ee) is a Māori welcoming ceremony that includes speeches, cultural performances, singing, and concludes with the hongi (pressing of noses). It is most commonly used to welcome guests into a marae (traditionally Māori meeting house) but may also accompany events such as building dedications or funerals (tangihanga). For less formal occasions, a mihi whakatau — a shorter greeting ceremony — may be used instead. Powhiri are also frequently performed for special guests or tourist groups during cultural events. [Source: Wikipedia]

One of the most dramatic parts of the powhiri for non-Māori is the wero, or challenge, which takes place at the start of the ceremony. Three warriors approach the visitors with ceremonial weapons, performing fierce gestures, battle cries, and expressions. The first warrior represents Tūmatauenga, the god of war, while the third represents Rongo, the god of peace. The final warrior offers a rautapu—a leaf or carved token—signifying that the visitors (manuhiri) may safely proceed onto the marae-atea. Historically, the wero served both to display the tribe’s strength and to test the courage and intentions of the visitors.

Following the karanga (ceremonial call) by women of the host group (tangata whenua), both sides gather and take their seats. Elders and younger members participate in a series of speeches, typically beginning with the hosts and ending with the visitors. The final speaker from the manuhiri presents a koha (gift), which is placed on the ground and later accepted by a member of the hosts. Koha was traditionally food or a treasured object, though today it is often a monetary gift. The ceremony concludes when the tapu (sacred restriction) between the two groups is lifted through the hongi or a handshake, symbolizing unity and mutual respect.

Māori traditions for welcoming guests date back long before European arrival and originally served practical purposes. As visitors approached a settlement, women would call out to identify who they were and what their intentions might be. Warriors then performed the wero. Once it was clear the visitors came in peace, they were invited to enter, welcomed formally, and offered food. Modern Māori welcomes still follow this pattern. While details of the ritual vary between iwi and regions, the underlying sequence remains the same: the karanga by women, the wero, formal speeches from both hosts and guests, and finally the hongi, symbolising peaceful meeting and mutual respect. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

A pōwhiri can include laments for the deceased, traditional songs,chants, and wero. Many are low-key and informal. Regardless of their size, pōwhiri end with an invitation for the manuhiri (visitors) to mingle with their hosts, the tangata whenua, and eat and drink with them. The manuhiri are no longer potentially threatening strangers but rather guests to be cared for as long as they remain in the hosts’ territory. Providing plentiful food for guests is central to Māori custom.

The Haka

The haka of the Māori is one of the best-known cultural traditions of Polynesia. This form of expression, sometimes referred to as a dance, is accompanied by chants, song and body percussion created by clapping hands, stamping feet, and slapping thighs. There is a leader and a chorus that responds to the leader’s calls. The energetic, aggressive postures are often the same as those used in the past before wars and fights. [Source: J. Williams, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

According to thehakaexerience.com: The haka is a type of ancient Māori war dance traditionally used on the battlefield, as well as when groups came together in peace. Haka are a fierce display of a tribe’s pride, strength and unity. The words of a haka often poetically describe ancestors and events in the tribe’s history. The Haka is definitely something amazing to behold when performed well and it requires strict discipline. It is a great character-building exercise with the power to connect the performers to themselves, their past and their present. Tapeta Wehi — a world authority in kapa haka (Māori performing arts), a leader of the renowned Te Waka Huia group, and the co-founder and director of The Haka Experience — is a great believer in the power of the body, where every muscle and sinew should burn with virility to exude emotion, to display anger, abhorrence, protest or love, tenderness and grace. The Haka allows the performer to display this like nothing else.

Today the haka is used by New Zealand national rugby team to intimidate their opponents before game sand celebrate victories. The “haka” asserts strength and has traditionally been associated with challenges, wars, battles, and intimidating rivals. It features karate-chop arm movements, stomping, posturing, yelling, grimacing, taunting and threatening gestures such as rolling of the eyes and sticking out the tongue. Māori chanting follows strict rules of performance, rhythmic structure, and continuity. Breaking a chant in the middle is taboo — as it has traditionally been believed that to be midstream would invite disaster, or even death, for a community. These chants often recount genealogies or the exploits of ancestors.

Haka Types and How To Do Them Properly

According to thehakaexerience.com: There are many forms of Haka where, performed both with and without weapons: 1) The Tutungaruhu (a dance by a party of armed men who jump from side to side); 2) Ngeri (a short Haka with no set moves performed without weapons to face with the enemy); 3) Haka Taparahi (performed without weapons); and 4) Peruperu (a dance with weapons where the men leap off the ground up and down performed face to face with the enemy. [Source: thehakaexerience.com]

Today, haka are still used during Māori ceremonies and celebrations to honour guests and show the importance of the occasion. We see this at many different occasions or gatherings.Tapeta Wehi, Founder Of The Haka Experience says: “I believe a Haka should be controversial and challenging. Whatever the occasion, I see the lyrics as the most important aspect; the tune, the rhythm and body movement are purely the vehicles for the communication of its message.” The uniformity of movement and message is what should be pursued. The message should always be paramount, the Reo (chants) therefore becomes a crucial component to the Haka. Haka has always been associated with war but in today’s World, the wars are not hand to hand combat but have been politically oriented.

Your stance should be that of a Whare nui (meeting House).The head is alert and vigilant like the tekoteko, the arms stretched out like the Maihi, the chest should be erect like the Whare, The body must stand fast, not sway, the stance must be firm when you see all these aspects together you will be filled with awe! The hairs on the back of your neck will stand on end!

History of The Haka

The haka chant often tells a story. The Ngati Toa haka Hana with the famous "Ka mate, Ka mate," which "tells the story of Te Rauparaha (1760s – 1849) — a powerful Māori leaders during the Musket Wars — who was being chased by enemies and sought shelter where he hid and came out into the light after his enemies were gone.

According to Māori tradition, the first kapa haka (performing group) originated with the women of Tinirau. Their mission was to capture Kae, who had killed and eaten Tinirau’s pet whale, Tutunui. Tinirau had allowed Kae to ride Tutunui home, but when they arrived, Kae refused to dismount. The whale struggled to throw him off, became stranded, and was slain and eaten by Kae. When Tutunui did not return, Tinirau realised what had happened and sought revenge. [Source: thehakaexerience.com]

He gathered his most talented women performers and sent them to find Kae, whom none of them had seen before. They were told they would recognize him by the distinctive gap in his teeth—and to reveal it, they would need to make him laugh. The women travelled to Kae’s village, performed songs, dances, and chants, and ended with a powerful haka. Their performance delighted and amused the audience so much that Kae laughed, exposing the gap in his teeth. Using a sacred incantation, the women rendered him unconscious and took him back to Tinirau, who killed him in vengeance for Tutunui. According to some iwi, this event marks the origin of the haka and the first kapa haka performance in Māori tradition.

During a tour of Asia and Oceania in 1997, the pop group Spice Girls got into big trouble for doing a haka. Upon hearing that female pop group performed the haka, one Māori politician fumed, "It is totally inappropriate. It is not acceptable in our culture, and especially from girlie pop stars from another culture." During a promotional visit to Bali, Indonesia, the Spice Girls twice performed a type of haka after two New Zealand rugby players among the 100 spectators offered to show them a version of the dance. Spice Girls manager Bart Cools said the artists did not mean to mock Māori culture. “They absolutely did not want to anger anyone,” Cools said. On another occasion, a group of Auckland businessmen were assaulted by Māori men for allegedly mocking the haka. [Source: Associated Press, April 28, 1997]

In 2024, New Zealand right-wing politician David Seymour introduced the Treaty Principles Bill, which critics aid aimed to "eliminate dedicated land, government seats, health care initiatives, and cultural preservation efforts granted to the Māori people under the Treaty of Waitangi. During the vote, 22-year-old Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke — New Zealand’s country's youngest-ever member of Parliament — interrupted the session and led the haka and and ripped a copy of the bill in half! The video of this went viral. In an interview with RNZ, Ngati Toa chief executive and rangatira Helmut Modlik said the haka was relevant to the Parliament session, considering Māori rights were up for debate. A haka can be "a show of challenge, support, or sorrow," per the outlet. [Source Morgan Sloss, BuzzFeed, November 19, 2024]

Māori House-Opening Ceremony

Tā i te kawa literally means to strike with a branch of kawakawa. This was a ceremony carried out in connection with the opening of a new carved house, or the launching of a new canoe. It could also occur at birth, or during a battle. [Source: Te Ara, the Encyclopedia of New Zealand]

A special tapu attaches to the timbers of a newly-carved house, because the trees which have been felled to build the whare are the sacred children of Tane-mahuta, the God of the Forest, and because they have been carved into the semblance of revered ancestors and into representations of national and tribal deities. The tapu must be laid, its dangerous powers averted, before the house can be occupied safely. This priestly ceremony of quelling the mystic influences of danger is termed whai-kawa, or kawanga-whare, also taingakawa o te whare. The hau tama-tane and the hau wahine, the male and female principles, co-operate in the removal of the tapu. [Source: Victoria University of Wellington]

A peculiar sanctity surrounds all the operations of constructing an important carved house, from the felling of the tree to the day that the last worked slab is placed in position. The carvers of to-day are very careful not to infringe any of the unwritten laws of the art and of tapu. Neither they nor any of the people would ever think of using the chips and shavings from the carvings for a fire for cooking food; neither will a workman blow the shavings off while he is engaged with chisel and mallet and axe. The breath is pollution; he turns the timber on its side and shakes the shavings off, or brushes them away.

One anthropologist witnessed the ceremony in 1908 in the Tuhourangi village at Whakarewarewa. It was the taingakawa of the carved meeting-house “Wahiao”, built by Mita Taupopoki and his kinsfolk, a house richly adorned with whakairo designs without and within. Taua Tutanekai Haerehuka was the tohunga (priest) who recited the ancient rhythmic form formulae for the purpose of freeing the new house from the tapu of Tane's woods that clung to it. [Source: Victoria University of Wellington]

In the carved bargeboards on the front of the house were placed the chisels, the bone and wooden mallets and the axes and adzes used by the carvers in their work. These tools were sacred for the time being, and special karakia were pronounced over them. With a taiaha weapon in his hand, a kiwi-feather cloak about him, Tutanekai advanced to the right front of the house and stood there by the side of the spiral-carved maihi or gable bargeboard.

Another kawanga-whare which I witnessed was that of the beautiful carved house “Rauru,” at Whakarewarewa, in 1900. It was remarkable because of its curious story of a fatal tapu which attached to some of the carvings, and because the two tohungas who performed the karakia both died soon after the ceremony, old Rangitahau of Taupo, in eight days, and, Tumutara Pio, of Te Teko, a little later. There was mutual jealousy, and the people say they fatally bewitched each other.

Māori House-Opening Invocations, Chants and Rituals Ceremony

In a quick level voice the tohunga (priest) he recited his charms to propitiate the spirit of the sacred forest of Tane-Mahuta. The translation of the opening karakia (invocation) is as follows: “For the felling of the Tree: “King of the forest-birds, chief of the parakeets that guard Tane's mighty woods, Tane's sacred resting place (listen to my prayer)! Tane (the Tree) stood erect, stood erect, amidst the forest shades; but now he's fallen. The trunk of Tane has been severed from the butt; the stump of the tree felled to build this house stands yonder in the sacred resting place. The branehy tree-top, the leafy head, has been cut off; it lies yonder in the Vast-Forest-of-Tane. I have performed my ceremonies of propitiation; I have appealed to the spirits of our priestly ancestors, and to the sacred ones. I have struck these timbers with mallet and chisel; I have struck them with the axe of the Sounding-Seas. I have mounted upon the great foaming girdle of the sea-god Tangaroa, the waves beaten down and divided by the canoe Nuku-tai-maroro. I am seeking, searching for the descendants of the children of Rata, to carve these timbers for me. I found them not; they were slain at the river Pikopiko-i-Whiti. O ancient ones, return and aid me on this our sacred day.” [Source: Victoria University of Wellington]

The kakariki powhaitere invoked in the first lines is the bird which is said to lead the flocks of parakeets in the forests; it is in Māori mythology the guardian of the sacred woods of Tane-mahuta. The leader of the parakeets is an ariki, “a priest and king” of the birds. The karakia appeals to the bird for its help and sanction; the ancient belief was that if the forest-creatures were not appeased by supplication and pious rites when a great tree such as a totara was felled by axe and fire, the birds and the fairies would set it up again during the night. Rata, mentioned in the chant, was a Polynesian chief and canoe-voyager who lived centuries ago in one of the islands of Polynesia, probably Upolu, in the Samoa Group; the lines alluding to Rata and his children memorise the fact that he and his people were carvers and canoe-builders.

The second karakia in the ceremony was for the removal of the enchantment of the carvers' sacred implements, and of the tapu attaching to the carving of the trees into the semblance of gods and of sacred ancestors. It began: “Takina te kawa o te whare e tu nei, he kawa tuatahi” — “Rehearse the sacred ritual of the house standing here, the first tapu-avertig spell,” and so on to the tenth kawa or charm for the lifting of the tapu. Then the chant proceeded: — “This is the prayer of Maru-te-whare-aitu, of Maru-whakawhi-whia” [deified ancestors of the Arawa tribe], “the prayer of the house Hau-te-Ananui” [a great whare-maire, or sacred house of instruction for the priests, which stood in ancient times in Arorangi Pa on the eastern slopes of Mokoia Island]; and ended with these words, always used at the end of invocations of this kind: Whano, whano, Haramai te toki, Haumi e! (“Bring hither the axe, 'Tis finished!”)

The last two lines were repeated by the assembled people in a chorused shout. As Tutanekai recited the Kawa he struck with his taiaha the various carved slabs and posts on the front of the house. The third and final kawa was the “Ruruku o te whare,”an appeal to the gods to make the house stable and firm, to avert all accidents and ills, and make it a warm and pleasant dwelling-place. This invoked the gods to bind firmly and make strong and fast the various parts of the house, so that all its posts and pillars, its rafters and beams and carved slabs, its thatch and roof might stand firm and never be overturned. Then the chant proceeded into a true house-warming prayer. Here the house is considered as Tane the Tree god personified:. This is a translation of the invocation: “Bind, bind together that all may be firm and steadfast, so that into thee, O Tane, may enter not the cold and stormy elements, the Frost-wind, the Great Rain, the Long Rain, the Cold Sleety Rain, the Hailstones; that thou mayst stand against the assault of the Mighty Wind, the Long-prevailing Wind, the tempests of the wind god Tawhiri-matea! May all be warm and safe within thy walls! These shall dwell therein — Warmth, Heaped-up Warmth, and Glowing Heat, Joy and Gladness, these are the people who shall dwell within Tane standing here before me! Now 'tis done! Bring hither the axe, and bind it on. Our work is o'er!” And as Tutanekai ended, all the people cried: — “Haumi — e!, Hui — e, Taiki — e!”

The final act in the ceremony was the takahipaepae, treading the threshold. In accordance with immemorial custom this was done by a woman, on of ariki rank, a Ruahine, being chosen for the crossing of the door-sill, so that the house might henceforth be free to women to enter. This woman was Meré Kanea, daughter of Mita Taupopoki, and cousin of Hune, the chief carver. Tutanekai, the tohunga, accompanied her, and gave her the customary-sacred food, a kumara which had been cooked in a tapu oven, the “fire of Ngatoro-i-rangi,” one of the boiling springs. This was finally to remove the tapu from the interior of the building, so that food might be brought into it, and that people might eat and sleep there without fear.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025