Home | Category: History and Religion

FIRST EUROPEANS IN NEW ZEALAND

The Dutch captain Abel Tasman and his crew were the first Europeans to lay eyes on what is now New Zealand. They sighted the west coast of South Island in 1642 and called it "Staten Landt", which means the “Land of the (Dutch) States-General,” because he thought it was could possibly be connected to Staten Island (Isla de los Estados) off Tierra del Fuego, discovered by the Dutch in 1616, and believed at the time to be the northern tip of the Great Southern Continent.

No other Europeans are known to have visited New Zealand after Tasman until Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy made three voyages to the Pacific Ocean and visited New Zealand in 1769, 1773, 1774, and 1777. In this period, he circumnavigated both islands, discovering New Zealand was made up of two islands, and mapped the coastline.

In the 1790s, New Zealand began to attract sealers and whalers from Europe and America who established the first settlements on the coast. In 1814 the first missionary station was set up in the Bay of Islands. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST EUROPEAN SETTLERS IN NEW ZEALAND AND THEIR IMPACT ON THE MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

BRIEF HISTORY OF NEW ZEALAND: NAMES, THEMES, HIGHLIGHTS, A TIMELINE ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MAORI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA BY EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Tasman’s Voyage to New Zealand

The Dutch captain Abel Tasman and his crew were the first Europeans to lay eyes on what is now New Zealand — in 1642, the same year Tasman sighted what is now Tasmania. They sighted the west coast of the South Island first and thought New Zealand was one land mass. Tasman was a navigator for the Dutch East India Company, which grew quite wealthy from trading spices from the Spice Islands, in what is now Indonesia, and trading silk and porcelain from China and Japan.

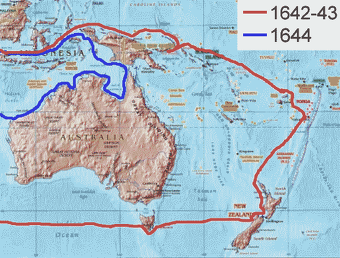

In August 1642, Abel Tasman left Mauritius, near Africa, missed Australia, found Tasmania in November 1642, continued east and found New Zealand in December 1642 , missed the strait between the north and south islands, turned northwest, missed Australia again and sailed along the north coast of New Guinea. In 1644, he followed the south coast of New Guinea, missed the Torres Strait, turned south and mapped the north coast of Australia.

Tasman embarked from Java with two ships and orders from the Dutch East Company to find if New Guinea was attached to Australia, and in the process found New Zealand, Tasmania and Fiji. Their voyage was considered a failure because they didn't discover any ways of making money.

Another one of Tasman’s missions had been to find the hypothetical southern continent of Terra Australis, which some said was full of fabled riches. Tasman wrote he hoped to discover the "remaining unknown part of their terrestrial globe" which "comprise well-populated districts in favorable climates and under propitious skies" and so "in the eventual discovery of so a large a portion of the world...be rewarded with certain fruits of material profit and immortal fame." Seeing that Tasman had not found any gold, interest in New Zealand was not strong, and it was over a hundred years later,

Tasman dropped anchor in what is now Golden Bay, a South Island inlet, in 1642 but never even made it ashore. His landing party was attacked by Maori war canoes and four Europeans were killed. What had happened, it is said, is that the Maori blew conch shells as a greeting. The Dutch sailors responded by blowing trumpets, inadvertently challenging the Maori to a fight. After the clash, deciding it was best to leave well enough alone, Tasman named the land Nieuw Zeeland after Zeeland in the Netherlands and left. The place where the incident took place is also known as Murderer's Bay.

Captain Cook in New Zealand

Captain James Cook was the first Europe navigators to extensively explore and survey Australia and New Zealand. He was the first to circumnavigate the two main islands of New Zealand. Cook visited Australia and New Zealand on his first voyage, which began in 1769. Cook claimed both Australia and New Zealand for the English crown and set in motion a process that led their colonization by the British. He discovered that New Zealand was two islands not one.

Cook arrived on Coromandel Peninsula not far from where the Tahitian navigator Kupe is believed to have landed. He named his New Zealand anchorage Mercury Bay because he fixed New Zealand's longitude on the world map by charting Mercury's transit point across the sun. He also claimed the islands for King George III, named one region the "River Thames area,"

Cook claimed New Zealand for Great Britain, circumnavigated both islands and and thoroughly explored and mapped the coastline during three South Pacific voyages. He and his crew on the Endeavour, proved once and for all that the the main islands of New Zealand were just large islands and not the great southern continent whose existence had been assumed by the scholars of his day. During his visits, he added many names to the map of New Zealand. The name of the country, however, remained New Zealand.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: HIS LIFE, CAREER, DEATH AND CONTRIBUTIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

VOYAGES OF CAPTAIN JAMES COOK: SHIPS, CREW, MISSIONS, DISCOVERIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Europeans in New Zealand After Cook

After Cook, the only Europeans that ventured to New Zealand for many years were rowdy whalers and sealers and escaped convicts from New South Wales (Australia). Some of these people began settling in New Zealand beginning around 1795 mostly in transient camps and homesteads characterized by lawlessness and disorganized rules of land ownership. As a rule convicts in Australia stayed clear of New Zealand because they had been told if they went there they would be eaten by cannibals.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, lumbering, seal hunting, and whaling attracted a few European settlers to New Zealand. In the 1790s-1800s, the main ingredients of Maori-European (Pakeha) contacts were whaling, timber and the spread of disease. In the 1790s, small European whaling settlements sprang up around the coast. In the 1820s, some British ships that dropped off convicts in Sydney stopped by New Zealand on the return journey to pick up timber from massive sequoia-like kauri pines, which was used to make mats and spars for tall sailing ships. The first Christian mission station was set up in the Bay of Islands in 1814 by Samuel Marsden, chaplain to the governor of New South Wales.

The U.K. only nominally claimed New Zealand and included it as part of New South Wales in Australia. Concerns about increasing lawlessness led the UK to appoint its first British Resident in New Zealand in 1832, although he had few legal powers. [Source: CIA World Factbook]

In 1840, there were about 2,000 Europeans and 115,000 Maori in New Zealand. By this time the Maori were trading crops and land with the Europeans in return for firearms, which fueled intense intertribal warfare. In 1840, the United Kingdom established British sovereignty through the Treaty of Waitangi signed that year with Maori chiefs. In the same year, selected groups from the United Kingdom began the colonization process.

Sealers in New Zealand

Seals and sea lions were hunted another for their meat, oil and fur. Leather is sometimes made from seals. Commercial sealers traditionally drove the seals to a designated area and killed them with blow to soft parts of their skulls. Sealing — the hunting of seals — was widely practiced in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th century.

By that time Sealing was established around the coast of Australia and sealers travelled all around the Pacific. Fur seal skins were sold on the London market but more importantly was a tradeable commodity in China. When China had a monopoly on the international tea trade, sea skins were traded for tea. The Chinese found little of value in the normal trade goods offered by European traders. They demanded payment in gold. Seal skins were a good alternative. [Source: New Zealand History 1800 -1900, A blog to assist the students in Level 3 NCEA History at Wellington High School, February 28, 2008 ]

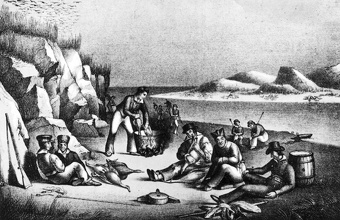

In New Zealand, the first Sealers set up camp in Dusky Sound (Fiordland) in 1792. Mainly ex-convicts, they were outfitted and supplied by entrepeneurs based in Port Jackson (Sydney). The job was simple. Kill as many Fur Seals as possible, skin them, cure the hide with salt and wait to be picked up. A good crew could return to Sydney with several thousand skins.

According to a blog on New Zealand history: Sealers were a rough and ready group. They settled in small groups around the southern coasts of both Islands. Sparsley populated by Maori their interaction remained relatively light. Most sealing operations were centred on the south coast of the North island, and both coasts of the South Island. These areas were lightly populated by Maori especially the South Island. This did not mean that their impact was not important but the gangs were not settlers. They lived close to seal colonies were there for a matter of weeks or months and left. They might return but it was an itinerant lifestyle and was often a different group of men. They rarely carried any trade goods thus there was little incentive for Maori to interact with them in anything more than a cursory nature. The impact of this interaction is limited by the areas that sealing took place.

It is limited by the few Maori who lived in these areas and their lack of trade goods. Some did become close to local Maori and were taken (See James Caddell) and some took wives and became apart of the tribe. In general their impact can be seen as introducing some Maori to Europe, their culture and the possibilities that they might offer. It would be the northern tribes who cashed in on this potential.

The first sealing 'gang' arrived aboard the 'Brittania' captained by William Raven, its skins were bound for China. Many ships would leave with at least 10,000 skins, one ship the (the aptly named) 'Favourite', landed 60,000 skins in a single trip in 1806.

Life of the New Zealand Sealers

Life for the sealers was rough. Often landed close to the Seals breeding grounds they were left on desolate coasts often hemmed in by cliffs and wild seas. Left with limited stores of food they endured bad weather, starvation and possible abandonment should their ship fail to return to pick them up. Sometimes shipwreck, meant their ship never returned. Sometimes bad debts and bailiffs stopped the ship from coming back. Some Captains simply found a more lucarative venture, leaving their men marooned. Abandoned gangs were left to forage for seabird eggs, crabs or merely to eat the rotting meat of their seals. Some attempted to build boats and if successful, to sail to safety. A gang from the 'Active' survived for 3 years before being discovered.

The greatest fear of all Sealers were the Maori. The thought that they might end up in a cooking pot terrorised them. Several gangs did disappear, probably to attack by local tribes. In 1817 Captain Kelly of the 'Sophia' was attacked by Maori. He and his crew fought them off then attacked their settlement. Captain Riggs of the 'General Gates' had a bad reputation in Sydney and it was no surprise that he apparently upset Maori in southern New Zealand who attacked two of his gangs, killing and eating them both over several days in 1823 and later in 1824. James Caddell was one sealer who was captured by Maori but who managed to become an accepted member of the tribe, becoming a Pakeha-Maori. In the 1820's a gang was attacked and John Boultbee recorded their escape and the help afforded by more friendly Maori nearby.

The impact on seals was more obvious. Within 20 years the Fur Seal was almost extinct on the New Zealand mainland. It would have a brief rennaisance in the 1820's when sealing gangs braved the southern waters and the sub-Antarctic islands, but by then the golden days were long gone. The overall effect of sealers can be hard to judge. They were relatively few and often virtually illiterate, most records of sealers are written by more respectable members of society who abhorred their way of life and culture. These records therefore can be seen as biased against them.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New Zealand Tourism Board, Wikipedia, Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet, BBC, CNN and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025