Home | Category: People and Life / Maori

MĀORI VILLAGES

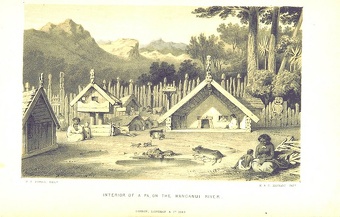

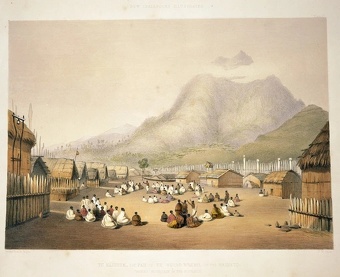

"Tu Kaitote, the pah of Te Wherowhero on the Waikato, Taupiri Mountain in the distance" by George French Angas,1847

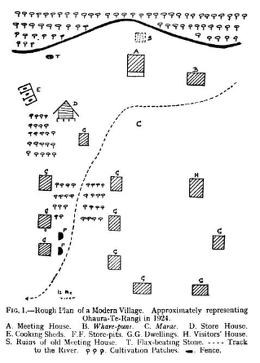

Māori villages traditionally have been orientated toward flat (or slightly lower) open ground, with the ‘back’ of the settlement closed in using the physical landscape, such as forest or higher ground. A social hierarchy has been associated to the layout, with restricted and sacred (tapu) uses near the entrance, and unrestricted and ordinary (noa) uses further into the settlement. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012 ^^]

In the past there were two types of Māori settlements: fortified (pā) and unfortified (kainga). The pa, where people took refuge during wartime, were typically situated on hills and protected by ditches, palisades, fighting platforms, and earthworks. Houses in the pa were tightly packed, often on artificial terraces. Kainga were unfortified hamlets consisting of five or six scattered houses (whare), a cooking shelter (kauta) with an earth oven (hangi), and one or two roofed storage pits (rua). Most farmsteads were enclosed by a courtyard with a pole fence. Most buildings were made of poles and thatch, though some were better constructed with posts and worked timber. [Source: Christopher Latham,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Important Concepts when choosing the location of a traditional village:

1) Ko ... toku waka (‘the canoe that brought me here is ...’) — defines the principle mode of transport for travel, trade and collection of resources. It also has associated prestige, and suggests the origin of the people.

2) Ko … toku maunga (‘the mountain that I associate with is …’) — locates the settlement in New Zealand, as well as an important source of materials such as stone for tools and (seasonally) birdlife for food

3) Ko … toku awa (‘the river that I associate with is …’) — defines the source of subsistence resources, such as drinking water and fish for food, hygiene and the principle transport route. ^^

RELATED ARTICLES:

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN THE PACIFIC REGION, POLYNESIA AND MELANESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI TATTOOS: HISTORY, HOW THEY WERE MADE, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

WAKA (MĀORI CANOES): HISTORY, TYPES, ART, HOW THEY ARE MADE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Marae

A marae is a sacred, communally-owned complex of buildings and grounds that serves as the focal point for Māori communities, representing a "place to stand" and belong (tūrangawaewae). “It has traditionally been the focal point of traditional Māori life. Māori gather there for meetings (hui), celebrations (āhuareka), welcoming ceremonies (pōwhiri), funerals (tangi), and celebrate important events such as weddings, christening and birthdays. It also a place where "challenges" are made, debates and discussions are held, old traditions and legends are kept alive, and youth are taught traditional songs, chants and dances.

A marae is composed of a meeting house (wharenui), a dining hall (wharekai), and an open central space (marae ātea). The word marae is often used to describe only the meeting house (wharenui). The marae atea (literally, the ‘hospitable clearing’) was traditionally an open space that was reserved as the principle and formal place for meetings and rituals, and to greet and converse with visitors, though not everyone was permitted to enter it. The marae atea is located adjacent to the entrance and would have been the first space one encounters. Only buildings with equivalent tapu (‘sacred; restricted’) status were constructed adjacent to the marae atea.. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

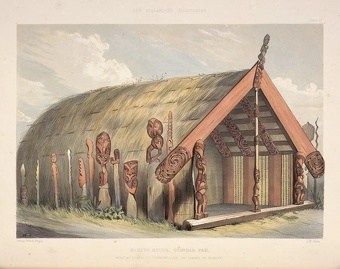

Marae buildings are often made from elaborately-carved totora wood painted with a red ocher "protective skin" to ward off evil spirits. Many of the carvings depict Māori gods and ancient legends. It is estimated that there are a thousand marae in New Zealand. Sometimes there serve as dining halls, churches, and places to put up visiting tourists.

The layout of a marae and the architecture of the buildings represents the body of the clan's male ancestor god, and the feasting room represent the body of a their female ancestor goddess. Master carver Clive Fugill told the New York Times, "the ancestor's spirits live inside the meeting houses... The rafters are the ribs and spine, the slanting facade outstretched arms, and the figure on the pinnacle the ancestor's face."

Wharenui (Marae Meeting Houses)

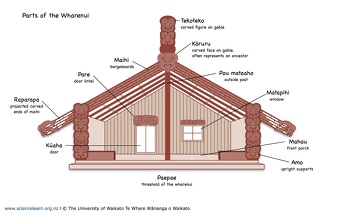

The main building of a Māori marae — the wharenui — serves as the focal point for gatherings, celebrations, and the care of the deceased. This structure, also known as a whare rūnanga (communal meeting house) or whare tipuna (ancestral house), is typically a beautifully carved building that represents an ancestor of the tribe and resembles the human body in its structure.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Large communal meeting houses served, and continue to serve, as important focal points for the community among the Māori. Richly adorned with carvings depicting ancestors and figures from Māori mythology, the meeting house functions as council chamber, guest house, community center, and gathering place for the discussion and debate of important issues.

Meeting houses are particularly important as places where the local group's history, customs, and genealogy are preserved and passed down to succeeding generations. The structure of the meeting house itself represents the body of a primoridial ancestor — the ridge pole of the roof is the spine, the rafters the ribs, the gable boards on the exterior the outstretched arms, and the gable ornament at the peak of the roof the face. The interior is extensively decorated with carved panels and other architectural members depicting powerful ancestors, both male and female. These ancestor images constitute a visual history of the group, simultaneously representing and embodying the spirts of its illustrious forebearers. Many represent prominent warriors who, in the past, fought to protect the community.

Orientation of Buildings in Traditional Māori Villages

The principle building in a Māori villages have traditionally been ithe marae near the entrance. Only structures and other spaces with tapu functions (such as the chief’s house) could front onto the marae atua, and helped to define this space. Other noa structures, such as cooking buildings and storage platforms, were kept at a distance from the marae atua so as not to disturb the tapu status.

The low-pitch to the roof which, though the tohu is supported centrally by the poutahu (central post supporting the ridge at either end) and the poutoko manawa (central post supporting the ridge at the centre of the building increases the lateral forces on the structure, putting increased horizontal pressure on the cantilevered wall posts. This was countered by the introduction of the hirinaki, which act as buttresses. The extra thickness to the walls’ structure also presented an opportunity to better insulate the building all round.

Close relationships between the design of houses and canoes are found throughout Polynesia.. In New Zealand one can see similarities in the construction techniques too. However, it is clear that a consideration of the local physical conditions radically influenced building design, and to some extent cultural practices within buildings.

The relationship between climate and vernacular architecture that developed in New Zealand is evident in the Karakia o te Kawanga Whare (prayer from a house-opening ceremony), which describes hat the design objectives were for the house, and emphasises that Maori building designers had a thorough understanding of what to expect from the local climate. Although there are regional differences across New Zealand, in adapting the design of buildings to suit the local context there is a marked homogeneity — particularly in the form of the whare puni. This suggests strong and regular connections between settlements and the sharing of practical and cultural ideas.

Archaeological evidence in New Zealand suggests that early Maori people continued the cultural practices that they were accustomed to from Polynesia. These practices varied on different islands but had consistent themes such as those defining a hierarchy of outdoor spaces — the spaces between buildings — as the principle areas of ritual and community activity. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

Henry Fisher wrote: It seems the location of buildings was principally to define the spaces between them, which is contrary to the European approach to space design throughout the same time period. Further, these buildings only ever enclosed a single space, suggesting that they were not intended to operate in isolation to their surroundings. Reinforcing this hierarchy of spaces was a strict format for locating the individual built elements in the settlement, so that their purpose and the social ranking of the user-group were closely related to those of the surrounding spaces.

The orientation of the settlement as a whole related to important elements in the surrounding landscape. Land closest to the coast was often reserved for high-ranking’ activities and habitation, with a diminishing hierarchy attached to both land and activity as one moves closer to the centre of the island.

In New Zealand there was a great deal of regional and local variation, but a generic pattern emerged that was informed by this Polynesian background. Initially, settlement across the two largest land masses has been described as ‘a constellation of “resource islands”’, connected by a network of seafaring coastal routes. Through time, the close connection to the coast became less marked, particularly as settlements moved further inland. There is evidence held in the oral history by the elders of many iwi suggesting a move away from the coast included — an attempt to evade the dangers of natural disasters, such as tidal surges and the recorded tsunami on the Nelson coastline in the 15th century. Over time, significant forms in the landscape, including mountains, forests, rivers and open land seemed to replace the coast–to-inland settlement layout.

Traditional Māori Houses

Traditional Māori houses, or whare, are typically rectangular in shape and built by family groups from materials like timber, rushes, and tree fern fronds, with a thatched roof, low door, and an interior hearth. While early dwellings were sometimes semi-permanent, larger architectural forms like the communal meeting house (wharenui) and elevated storehouse (pātaka) also existed. Over time, European influences led to the gradual adoption of European-style houses, particularly from the late 19th century onwards.

There were different kinds of traditional Māori houses. The houses where family’s lived were called whare puni (sleeping houses). They were designed for the cooler New Zealand climate with a low door and a central hearth for warmth. Families slept communally on mats on the floor. Mid-shipman Jonathan Monkhouse of the Endeavour, on visiting New Zealand in 1769, commented that the sleeping area inside traditional Māori houses was often defined by a woven mat or slightly raised platform, which would have helped to insulate against the ground.

Among the other types of traditional whare were Wharenui. The meeting houses described above, often elaborately decorated, used for communal gatherings and cultural events Pātaka, elevated storehouses, sometimes elaborately carved, used to keep food and valuable items (taonga) safe from pests and other threats; and kāuta, cooking houses for community use. In weaving houses women made flax skirts, mats, baskets and fishing nets.

Building frames were typically made from timber or small sticks. The walls and roof were constructed from natural materials like raupō (bulrush), toetoe, nīkau palm leaves, and other plant matter, sometimes with bark, and then thatched. The floors were typically earth covered with tough flax mats (whariki). Traditional Māori buildings retain the pitched roof supported on central and perimeter posts — the generic style found throughout Polynesia — they are distinguished by only enclosing a single space, covered with thick cladding, low roofs, few openings and a porch (roro). [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

Floor and Walls of Traditional Māori Houses

The floors of traditional Māori houses were typically made of compacted earth, covered with loose rushes and ferns except at the entrance and around the hearth. This provided a simple, durable, and easily maintained living surface. The compacted earth also acted as a thermal mass, storing and releasing heat to help moderate internal temperatures. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

The walls, however, represent perhaps the most significant adaptation of the broader Polynesian building model. In central and eastern Polynesia, house forms generally featured open sides, with temporary screens or blinds used to provide shelter from wind and rain. In contrast, the traditional Māori whare is distinguished by its fixed, thick walls. This difference is even reflected in the Māori language: while whare is a general term for “house” or “building,” puni specifically means “stopped up” or “enclosed.”

This architectural development was most likely a direct response to the cooler climate of New Zealand. The walls were filled and lined with locally available woven materials—most commonly kakaho (reeds of the toetoe plant)—using techniques related to those found in central Polynesia. The exterior was often clad with raupo (bulrush), though bark and other materials were also used where preferred thatching plants were scarce. This layering of materials enhanced both the insulation and durability of the structure, keeping moisture from penetrating beyond the outer layer. Regional variation further suggests that wall thickness differed across the country, reflecting local climatic conditions, available materials, and cultural preferences.

Roof of a Traditional Māori House

The roof of the traditional Māori houses was generally a simple double-pitch form, with deep overhangs to the sides, and gable ends that often extend at the front to create a covered porch (roro). The roofs were clad in a thick thatch of raupo that was supported by an open-weaved mat, much like a net. The thatching was often heaped on to such a depth that a more rounded profile was formed. Parallel roof styles have been recorded in Hawaii where the response to the local climate was similar. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

The use of an open-weaved mat beneath the cladding supports the strong belief that the construction of the canoe and the house were closely linked. This is demonstrated by the work of Mau Piailug in his work on re-constructing the tradtional Hawaiian voyaging waka Hokule’a in the 1990s. Such migratory waka would have included shelters on-board.

Roof pitches in New Zealand are markedly lower than those found throughout Polynesia, and it has been suggested that this was a response to the cooler climate, to heat the internal space more efficiently. Lowering the pitch would also have had likely effect of increasing the lateral forces acting on the walls, despite the central supporting posts, and thus developed the form further. Thickening the walls and securing the additional timber element — the hirinaki — would have helped reduce this effect. A common alternative to the double-pitch was the barrel-shaped roof and roof slopes running all the way to the ground were not uncommon. These forms would have helped reduce the problem of lateral loads on the walls.

Openings in Traditional Māori Houses

Openings in traditional Māori houses were typically limited to a single doorway and one small ‘window’, most often located on the same gable end (whether or not a roro was present). This contrasts sharply with other Polynesian building traditions, where open-sided structures were common. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

The key design motivation appears to have been heat retention. Thick walls, a solid roof, and a compacted earth floor enabled the house to retain warmth from the internal hearth, while minimising openings reduced heat loss. Consequently, the doorway was made just large enough to allow entry by crawling, and the ‘window’ served primarily for ventilation rather than light. Given its recessed position beneath the roro, this placement was practical but did little to illuminate the interior.

Designers of traditional Māori houses faced challenges familiar to builders in New Zealand today: achieving an effective balance between ventilation, heat retention, and natural light. Ethnographer Elsdon Best observed that “by no stretch of the imagination can the whare Māori, or native house, be viewed as a comfortable place,” noting reports of Europeans choosing to sleep in the more open kauta (cooking shelters) rather than endure the smoky interior atmosphere. Sydney Parkinson (1769) also recorded Māori efforts to improve air circulation, describing houses with “the door on one side, and very low; their windows at one end, or both.” It is also probable that these houses were oriented to take advantage of prevailing winds, demonstrating a sophisticated environmental awareness in traditional Māori design.

Roro (Porch) of a Traditional Māori House

The roro (porch) represents a distinctive development within the vernacular architecture of New Zealand. In most examples, it occupies between 8 and 24 percent of the total length of the traditional Māori house. The roro is now generally interpreted as an extension of the outdoor space adjacent to the building—specifically the marae ātea when the house belongs to a family group of some standing within the settlement—rather than as an external architectural component of the structure itself. This interpretation reinforces the earlier discussion in this paper that the principal spaces of Māori settlements were located outdoors, in the open areas between buildings. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

The development of the roro was likely a response to the local climate, addressing environmental challenges not encountered in the design of the marae ātea elsewhere in Polynesia. The marae ātea may have been constrained by its strong ritual significance, which discouraged alteration to its traditional open form (apart from the absence of stone construction in Aotearoa). In contrast, the adjoining spaces carried fewer tapu restrictions, allowing for architectural adaptation. The roro thus afforded a sheltered extension of the marae ātea into the whare-puni (sleeping house), bridging outdoor and indoor realms.

At this point, the concept of the threshold becomes particularly relevant, as the roro occupies a transitional zone between two significant environments. Two thresholds were especially emphasised: the first, a timber beam along the front edge of the roro at ground level, known as the paepae kainga āwhā; and the second, the carved lintel over the doorway, or korupe. These boundary elements may have conferred a degree of leniency in the tapu status of the roro’s floor, reflecting its intermediate position between sacred and everyday spaces. As Deirdre Brown notes, a variety of daily activities took place here: “the porch being the preferred place [over the building’s interior] for sheltered relaxation, eating, industry and possibly sleep.” Illustrations by G. F. Angas further show that the roro could also serve as a setting for tapu rituals, emphasising its dual spiritual and domestic functions.

The consistent design and orientation of traditional Māori houses, along with the need for a cleared area in front, also shaped how the interior spaces were culturally organised. A typical floor plan reveals divisions within the house that were symbolic rather than structural, since there is no evidence for internal partition walls in New Zealand. The internal spatial hierarchy mirrored that of the wider settlement, with status descending as one moved further from the marae ātea. The area adjacent to the ventilation opening held the highest prestige, reserved for people of elevated rank.

It is plausible that the influence of climate on architectural form—creating interiors that were warm yet smoke-filled—also affected spatial use, with high-status occupants choosing to sit or sleep in the least stifling areas. Moreover, the traditional tapu–to–noa transition that structured exterior spaces may have contributed to keeping the ventilation opening (and its associated high-status area) at the front of the building, discouraging the addition of further openings elsewhere. In this way, both environmental conditions and cultural values played integral roles in shaping the remarkably consistent form of traditional Māori houses across New Zealand. While regional variation did exist in the orientation of houses relative to the marae ātea and the positioning of the roro, these differences did not fundamentally alter the hierarchy of spaces or the cultural relationships between them.

Decorations on Traditional Māori Houses

The decorative elements of traditional Māori houses reflect a shared Polynesian construction language, adapted through the use of local materials. Carefully and often beautifully crafted flax twine and rope were used to bind timber components and secure cladding and linings. [Source: Henry Fisher, an introduction to the vernacular architecture of New Zealand, Victoria University of Wellington, 2012]

These techniques reveal clear parallels with canoe construction. One example is the combined use of wedges and flax bindings—a method that, in canoe-making, allowed the lashings to be tightened quickly after storms or heavy weather. It is likely that similar considerations for local environmental conditions—such as strong winds and the effects of earthquakes—accounted for the continued use of this binding method in building construction.

The styles of adornment were influenced by material choices. Archaeological evidence suggests that designs were fairly simple and geometric from the 1200s to the 1500s, as seen in the decorative carving of hardwood elements such as lintels and beams around the entrance. However, intricate carvings began developing rapidly from the 1500s onward with the widespread use of pounamu (nephrite or greenstone) as the primary stone tool. Pounamu is harder than other stones found in New Zealand and retains a sharp edge much longer, enabling more detailed carvings.

This technological advance and the increased use of a local material appears to have influenced cultural practices, as adornment became more prevalent on chiefly houses and other important buildings in the settlement, such as pataka whakairo (carved storehouses), reflecting the mana (status) of the chief and his family. Adornment remained oriented towards sacred marae areas and other tapu spaces, often leaving the back of the building—facing spaces of noa status—completely unadorned.

A Pataka (storehouse) (Te Huringa I, 1839) was carved by Te Metara and others and is made of totara wood and paua shell. Food and precious objects were stored in the pataka. Carvings that exemplify the link to ancestors were elaborated on the building.

Gable and House Post Figures in Māori Buildings

A Pou tokomanawa (male post figure) (Te Huringa I, 1800–1900) from the Wairoa region was made of totara wood and paint. Pou tokomanawa (central support posts) stand in the center of a meeting house. They extend up to the ridge pole which supports the roof. Many Pou tokomanawa have a male or female ancestor carved at the base. The female Pou tokomanawa symbolizes the power to give birth and sustain life. The male figure emphasizes the power of procreation. One hand grips his genitals, while the pendant around his neck links him to his ancestors. [Source: Māori Treasures from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Tokyo National Museum, Heiseikan Special Exhibition Gallery 1 & 2, January — March 2007]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a House Post Figure (Amo) made of wood and date to around 1800. It originates from somewhere in New Zealand and measures 109.2 × 27.9 × 12.7 centimeters (43 inches high, with a width of 11 inches and a depth of 5 inches). According to museum: Depicting an ancestor from the Te Arawa region, this panel once adorned a Māori meeting house and may depict an ancient warrior. The sense of fierce movement conveyed in the stylized depiction of the arms indicate's that the figure is likely engaged in a war dance, while his tongue is thrust out in defiance of his people's enemies. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection is also home of a gable figure (Tekoteko) dating to the 1820s, it originates from somewhere in New Zealand and is made of wood and paint and measures 66 × 28.6 × 8.3 centimeters (26 inches high, with a width of 11.25 inches and a depth of 3.25 inches) According to the museum: This imposing tiki once adorned the roof peak of one of the major buildings in a Māori village, likely that of a storehouse (pataka), belonging to the village chief and used to safeguard food, tools, weapons, and other items.

Each gable ornament depicts a founding ancestor, the progenitor of the group (iwi) of which the community forms a part. In this image, the ancestor grasps a kotiate (a type of hand club) firmly in his right hand. The kotiate was used in hand-to-hand combat, and its presence suggests that this ancestor was an accomplished warrior. Probably carved in the 1820s, this work, which was collected soon after it was made, still preserves its original polychrome paint.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Each tekoteko depicts a founding ancestor, the progenitor of the group or iwi of which the community formed a part. Like all major ancestors, the figure is depicted standing, from a frontal perspective. His muscular limbs spread in an imposing stance, the ancestor stares down at the viewer with wide eyes and mouth agape, giving an impression of strength and martial prowess that is enhanced by a kotiate (a type of hand club) firmly grasped in his right hand. The kotiate was used in hand-to-hand combat in a manner similar to other Māori hand clubs and its presence here suggests that, like many tupuna, this ancestor was an accomplished warrior. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The eyes would originally have been completed by iridescent inlays made from paua shell , a relative of the abalone. The figure is flanked by smaller tiki, who stand upon his shoulders; his feet and phallus rest upon a large human face, likely representing another ancestor, which lacks the elaborate relief carving seen in the other images. Probably carved in the 1820s, this work appears to have been collected not long after it was made and still preserves its original polychrome paints made from kokowai (red ocher), charcoal , and white pipe clay.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025