Home | Category: History and Religion / Maori / Government, Economics and Agriculture

MĀORI KING AND QUEEN

The Māori monarch is a mostly ceremonial role with no legal status. But it has enormous cultural, and sometimes political, significance as a potent symbol of identity and kinship. The coronation takes place on a high-backed wooden throne during an elaborate ceremony on the country's North Island in which the new monarch is ushered to the throne by a phalanx of bare-chested and tattooed men bearing ceremonial weapons. The new monarch wears a wreath of leaves, a cloak and a whalebone necklace.[Source AFP, September 5, 2024]

There have been eighth Māori monarchs, six kings and two queens. The position of Māori monarch is not hereditary by right. Leaders of the tribes associated with the Kingitanga (Māori King movement) appoint a new monarch on the day of the previous monarch’s funeral and before burial. The process of electing a successor is guided by a privy council. The role of the Māori King and Queen is very different from the role of the monarch of New Zealand — the British monarch. When Kingitanga was established in 1858, it was hoped that by creating a King, Māori tribes could deal with the settlers on a more equal political footing. [Source: Monarchy New Zealand]

More than 150 years later, the role of the Māori King has evolved tremendously, but remains very important. The Māori monarch has no constitutional role, but has a significant symbolic role. The Māori monarchy continues to operate today as an enduring expression of Māori unity. It plays an important cultural and social role in Māori communities and the wider New Zealand identity.

The Māori monarch is responsible for hosting or attending numerous Māori gatherings and ceremonial occasions, not least her annual koroneihana (coronation) celebrations, Each year he or she makes a series of annual visits (poukai) to Kingitanga marae, which provided an opportunity for people to see the monarchs at their home marae and discuss the issues of the day. The monarchs also travel the country to open buildings and exhibitions, and to attend events such as the tangihanga (funerals) of tribal leaders.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MĀORI GOVERNMENT: KING, QUEEN, POLITICS, CHIEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE OF NEW ZEALAND: MODELS, IMPACT AND LATE ARRIVAL ioa.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MĀORI: ORIGIN, ARRIVAL IN NEW ZEALAND, LIFE, WARFARE

ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI AFTER THE ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI: POPULATION, LANGUAGE, CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CUSTOMS: ETIQUETTE, THE POWHIRI AND THE HAKA ioa.factsanddetails.com

CUSTOMS AND ETIQUETTE IN THE PACIFIC REGION, POLYNESIA AND MELANESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI RELIGION: TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, CHRISTIANITY, CEREMONIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI SOCIETY AND FAMILY: MARRIAGE, KINSHIP, MEN AND WOMEN ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI LIFE: FOOD, SEX, CLOTHES ioa.factsanddetails.com

TRADITIONAL MĀORI BUILDINGS, VILLAGES AND HOMES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MĀORI CULTURE AND ART ioa.factsanddetails.com

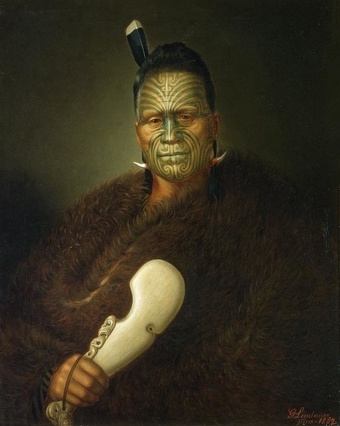

MĀORI TATTOOS: HISTORY, HOW THEY WERE MADE, SMOKED HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Kingitanga

The Kingitanga (Kiingitanga), or Māori King movement, was founded in 1858 to unite New Zealand's tribes and provide a single counterpart to the colonial ruler, Britain's Queen Victoria. "People think Māori people are one nation — we're not. We're many tribes, many iwi. We have different ways of speaking out," Joanne Teina, a Māori, told AFP. "The Kiingitanga was created to create unity — among people who were fighting each other for thousands of years, before Pakeha (Europeans) came along." [Source AFP, September 5, 2024]

The Kīngitanga is one of the most enduring Māori institutions to arise during the colonial era and remains among New Zealand’s longest-standing political movements. When Europeans first arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand, there was no single Māori sovereign. Instead, iwi (tribes) operated autonomously under the authority of their own rangatira (chiefs). By the 1850s, however, Māori communities faced mounting pressures from the rapid increase of British settlers, political marginalisation, and growing demands from the Crown to acquire Māori land. Opinions among Māori were divided—some were willing to sell land, while others resisted. [Source: New Zealand Government]

Many Māori observed that British power and stability stemmed from unity under a single monarch. This belief was especially strong among leaders who had visited England and witnessed its institutions, industry, and legal system firsthand—such as Piri Kawau (Te Āti Awa), who met Queen Victoria in 1843, and Tamihana Te Rauparaha (Ngāti Toa), who met her in 1852. Inspired by these experiences, they envisioned a pan-tribal Māori kingship that could end intertribal warfare, safeguard Māori land, and establish an independent Māori governing authority equal in status to the British Crown.

The Kingitanga movement demonstrates the appeal of monarchies. A monarch is a person of great mana, dedicating their lives to the service of others. He or she is a focal point for culture, and a living symbol for a people or nation. The Māori King operates exclusively on a cultural level. The British monarch also operates on a cultural level, though he or she works on a constitutional level as well. The roles of the Māori monarch and the New-Zealand-British monarch do not conflict. They enhance each other, allowing both monarchs to better represent New Zealand, according to the New Zealand government]

First Māori King and Ones Who Refused

The first Māori king was Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, who was installed in 1858 and reigned until his death in 1860. His purpose was to promote unity among the Māori people, and his coronation established the Māori monarchy. He was a powerful nobleman and warrior chief from the Waikato tribe. Chiefs selected him to be a unifying figure for the Māori people. Upon his death in 1860, his son, Tāwhiao, succeeded him as the second Māori King.

Both Kawau and Tamihana initially thought they might become king. However, Kawau had admitted to Queen Victoria that Potatau Te Wherowhero of Waikato was the most powerful chief in New Zealand, while Tamihana was reminded by his father, the famous chief Te Rauparaha, that his people had been forced to leave Kawhia by the powerful Waikato.

Te Kani-a-Takirau from the East Coast famously refused the kingship, saying:

Ko taku maunga ko Hikurangi,

He maunga tu tonu

Ehara i te maunga haere.

Ko toku Kingitanga

No tua whakarere,

No aku tipuna o te Po!

My mountain is Hikurangi,

It is an enduring mountain,

It is not a mountain that travels.

My kingship is from time immemorial,

Handed down from my ancestors.

Choosing The Second Māori King

From 1853, Mātēne Te Whiwhi of Ngāti Raukawa, supported by Tamihana Te Rauparaha, travelled throughout the central North Island promoting the idea of establishing a Māori king to unite the Māori people. Te Whiwhi first sought support from the ariki (hereditary chiefs or nobility), beginning with Tōpia Tūroa, the paramount chief of Whanganui. Tūroa declined the proposal, saying, “I must decline. My mountain is Matemate-a-onga. My sea is Whanganui, and the fish in it are the toitoi and whitebait.” [Source: New Zealand Government]

Tūroa then suggested Iwikau Te Heuheu, paramount chief of Ngāti Tūwharetoa of the Taupō region. Te Heuheu also declined, replying, “Tongariro is the mountain, Taupō is the sea, and Te Heuheu is the man. He stands in the centre of the Island, and toward him flow the rivers from all sides. Look—the fish of those waters are kōkopu, kōura and kōaro.” Te Heuheu in turn nominated Te Amohau of Te Arawa, who likewise refused, saying, “My mountain is Ngongotahā, Rotorua is the sea, and the fish in it are kōura, kākahi and īnanga.”

Te Amohau suggested Te Hāpuku of Ngāti Kahungunu, who referred the offer to Te Kani-a-Takirau of Ngāti Porou. Te Kani-a-Takirau responded, “Indeed, I am of the lines of your noble ancestors, but I dwell on one side of the Island. Moreover, my mountain Hikurangi does not easily move from its resting place.”

In keeping with their chiefly dignity and humility, each of these leaders recognised that their authority was rooted in their own tribes and that they were not in a position to assume a kingship over all Māori. One after another, they declined the honour and suggested others in turn. Further approaches were made to Karauria of Ngāti Kahungunu, Tūpaea of Ngāi Te Rangi, and Pāora Kingi of Mātaatua, before the invitation was eventually sent back to Te Heuheu.

Queen Te Atairangikaahu (1966–2006)

Dame Te Atairangikaahu (1931–2006) served as Māori Queen from 1966 until her passing in 2006—the longest reign of any Māori monarch. She was the first woman chosen to lead the Kingitanga (the Māori king movement) and was the Māori queen for over 40 years.[Sources: Wikipedia; New Zealand Government; Rahui Papa and Paul Meredith, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, 2018]

Queen Te Atairangikaahu’s full name and title was Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu, with Te Arikinui meaning “Paramount Chief” and Te Atairangikaahu translating to “the hawk of the morning sky.” Her full whakapapa (genealogical) name—Te Atairangikaahu Korokī Te Rata Mahuta Tāwhiao Pōtatau Te Wherowhero—linked her directly to the six Māori kings who preceded her. Deeply respected across Aotearoa, her tangihanga drew thousands of mourners, both Māori and Pākehā, as well as dignitaries from around the world.

Born Pikimene Korokī Mahuta, Te Atairangikaahu was the daughter of King Korokī Mahuta. Korokī had two older daughters, the younger of whom was Tuura, from an earlier relationship with Tepaia. Known affectionately as Piki in her youth, she had whāngai-adopted siblings, including Sir Robert Mahuta, whose daughter Nanaia Mahuta would go on to become a member of Parliament and serve as New Zealand’s foreign minister from 2020 to 2023. A direct descendant of the first Māori King, Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, Te Atairangikaahu was educated at Rakaumanga Primary School and Waikato Diocesan School for Girls.

When King Korokī died in 1966, Princess Piki was crowned Queen Te Atairangikaahu before his burial, fulfilling a prophecy made generations earlier by King Tāwhiao: “Kei te haere mai te wā, ka puta mai i taku pito ake, he wahine, he urukehu, mana hei whakatutuki i tēnei oranga” — “The time is coming when from my loins a woman of fair complexion shall arise; she will lead the way to fulfilment and renewal.”

Under Queen Te Atairangikaahu’s leadership, and with the work of her stepbrother Sir Robert Mahuta, the long-standing issue of raupatu (land confiscations) was finally resolved. In 1995, the Waikato–Tainui tribe reached a historic settlement with the Crown, receiving compensation valued at $170 million, including the return of significant tracts of land—an enduring legacy of her reign. Around a half million New Zealanders tuned in to watch her funeral in 2006.

Early Life of Queen Te Atairangikaahu

Te Atairangikaahu was born at Waahi Pa on 23 July 1931, and it was said that a shooting star marked her birth. Piki, as she was known, was two when her father succeeded her grandfather to become the fifth Māori king. Piki had an older sister, Tuura, who was Koroki’s child from a previous relationship. Of the two girls, their grandfather, King Te Rata, declared, ‘Tuura is mine. Piki belongs to the world. Teach her well.’1 There were also several adopted children, including Robert Te Kotahi Mahuta. [Sources: Rahui Papa and Paul Meredith, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, 2018]

Piki grew up around the Waahi Pa settlement on the Waikato River, about 3 kilometers west of Huntly in New Zealand's Waikato region, and was attended by hawini (those who looked after the royal family). Educated at the local Rakaumanga Native School, she was groomed for leadership from an early age. Her great-aunt, Te Puea Herangi, prepared her to lead the Kingitanga if the rangatira (chiefs) chose her for the role. Te Puea was a hugely influential figure in her early life. At the age of 15 Piki was sent by Te Puea to Waikato Diocesan School for girls. She boarded at Te Rahui Wahine, a Methodist hostel for young women in Hamilton run by Sister Heeni Whakamaru and the Reverend A.J. Seamer, a retired minister. Here she acquired a knowledge of etiquette in the Pakeha world. At school she became a prefect and participated in sports such as fencing, hockey and swimming, and learned the piano and to read music. She also loved literature and poetry, and quoted verse at hui on several occasions.

While Te Puea wanted Piki to be comfortable in the European world, she considered it crucial that Piki retain a strong sense of communalism and not lose sight of her Māori identity. At home at Waahi Pa, the young princess could be found working in the communal gardens or the dining room. During the school holidays, she often stayed at Te Puea’s farm, where her tutelage continued. Te Atairangikaahu later commented affectionately that Te Puea ‘was hard on me’.

In December 1953, Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh were welcomed at Turangawaewae on their first visit to New Zealand. The government consented to a Waikato request that the royal couple stop outside Turangawaewae marae, but Princess Piki invited the Queen and Duke to come inside. They agreed, to the cheers of the assembled crowd. Princess Piki led the royal couple onto Turangawaewae and into the meeting house Mahinarangi, with Koroki falling back. Many saw this as signalling his endorsement of Piki as his heir apparent. For Waikato, the brief visit was a symbolic recognition of the mana of the Kingitanga. In his later years, King Koroki suffered from a prolonged illness. Princess Piki increasingly represented her father at tribal hui and other functions around the country, demonstrating her dignity and charm.

In November 1952, Pincess Piki she married Whatumoana Paki, whose father was from the Waikato iwi Ngāti Whāwhākia and whose mother was from the northern iwi Te Aupōuri. A tono (arranged marriage) had been expected for the daughter of the Māori king, but Piki was determined to choose her own husband. She fell in love with Whatumoana Paki of Huntly. Although he was the grandson of Hori Paki, a long-time servant of the Kingitanga, Piki’s influential great-aunt Te Puea was entirely and publicly disapproving. The couple married in a small private ceremony in Huntly a few weeks after Te Puea’s death. Princess Piki Mahuta became Princess Piki Paki and assumed the roles of wife and then mother. Together they had seven children: Tūheitia Paki, Heeni Katipa (née Paki), Tomairangi Paki, Kiki Solomon (née Paki), Mihi Gabrielle Paki, Maharaia Paki, and Te Manawanui Clarkson (née Paki).

Queen Te Atairangikaahu Reign

King Koroki died on 18 May 1966. During the six-day tangi, 48 visiting rangatira (chiefs) deliberated on who should succeed him. Some traditionalists within Waikato believed that the male line of succession should continue, and suggested Koroki’s cousin Charlie Tumate Mahuta. There was even talk that it might be time for the mantle of the Kingitanga to be taken up by the Te Heuheu paramount family of Ngati Tuwharetoa. However, in the end the rangatira’s decision was unanimous. Princess Piki was to succeed her father, with the title of Queen. The decision was conveyed to the grieving princess. She was reluctant to accept this title, preferring a Māori one such as ariki tapairu (a high-born chieftainess), but acceded to what the rangatira had decided. She made it strongly known, however, that she wished to mark her accession by taking the name of her mother, Te Atairangikaahu, who had died the previous year. [Sources: Rahui Papa and Paul Meredith, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, 2018]

On 23 May 1966, on the day of Koroki’s funeral and in accordance with the whakawahinga (raise up) ritual, the bible which had been used to consecrate Potatau Te Wherowhero and subsequent Māori kings, was placed on the head of Princess Piki by Te Waharoa Tarapipipi, a direct descendent of Wiremu Tamihana, the ‘kingmaker’ who had consecrated Potatau in 1858. Kingitanga spokesperson Henare Tuwhangai asked the assembly what her title should be. Suggestions of ariki, ariki toihau, and ariki taungaroa were met with silence. When Tuwhangai proposed kuini (queen), the now animated crowd responded in affirmation — ‘hei Kuini, hei Kuini, hei Kuini!’ (as a queen, a queen, a queen!). Princess Piki became Te Arikinui, Queen Te Atairangikaahu, and ‘te mokopuna a te motu’ (the child of the people) — an honorific referring to the fact that the Māori sovereign was elected by and belonged to the Māori people. In years to come, she would be known affectionately as simply ‘the Lady’.

As the first woman to lead the Kīngitanga and the first Māori Queen, Te Atairangikaahu assumed her mother’s name and quickly endeared herself to her people through her wisdom, grace, and humility. Among the Waikato, she was affectionately known as ‘The Lady’ and carried the title Te Arikinui with deep dignity. Throughout her reign, Te Atairangikaahu moved at ease amongst different communities and was as likely to be seen watching a rugby league match as at the opera or ballet. She was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1970, received an honorary doctorate from the University of Waikato in 1973, and in 1987 became one of the first two inductees—alongside Sir Edmund Hillary—into the Order of New Zealand, the country’s highest honour. In 1999, Victoria University of Wellington awarded her an honorary Doctor of Laws degree.

At Turangawaewae, Te Atairangikaahu welcomed New Zealand governors-general, prime ministers and other politicians, along with British and other royalty, foreign heads of state and ministers, diplomats and religious leaders. Among the many visitors were Crown Prince Akihito and Crown Princess Michiko of Japan in 1973, Queen Elizabeth in 1974, Secretary-General of the United Nations, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, in 1985, and Nelson Mandela in 1995.

The Waikato Raupatu Settlement in 1995 was a key event during Te Atairangikaahu’s reign. The settlement created optimism for the future of the Waikato iwi, though in the years that followed there were unprofitable investments and political infighting amongst the members of the new governance body, Te Kauhanganui, and its executive, Te Kaumaarua. Te Ataairangikahu lent her mana and influence to a number of causes. Among other roles, she was patroness of the Māori Women’s Welfare League and the kohanga reo movement. She was a tireless advocate for Māori women and for the importance of the Māori language for the young.

Dame Te Atairangikaahu celebrated the 40th anniversary of her koroneihana (coronation) in May 2006, though it was clear during the week-long celebrations that she was not well. In August 2006, after an extended period of illness, Queen Te Atairangikaahu died, less than a month after her 75th birthday. Her six-day tangihanga at Turangawaewae Marae was comparable to a state funeral. People came in their thousands to pay their respects, so many that the New Zealand Defence Force was brought in to help the marae feed the visitors. Such was her mana and the outpouring of grief that her funeral was broadcast live on three television channels, to more than 430,000 people. An estimated 100,000 visited Turangawaewae during the mourning period. Messages of condolences came from all around the world, including from Queen Elizabeth II.

After extensive discussions, Te Atairangikaahu’s eldest son Tuheitia was chosen to succeed her as Māori monarch. Following the tradition of the whakawahinga ritual, Tuheitia was consecrated next to the casket of his mother on the day of her funeral. Te Atairangikaahu was conveyed by her tribal waka (canoe) Tumanako down the Waikato River to the sacred mountain Taupiri Kuao. Thousands lined the riverbank, and a mass poroporoaki (farewell ceremony) was conducted at Taupiri. Te Atairangikaahu was buried in a private ceremony on the lower summit of the mountain, a place reserved for the Māori monarchs.

King Tuheitia (2006-2024)

King Tuheitia Pootatau Te Wherowhero VII (1955-2024) was crowned as Kīngi Tūheitia and reigned as the Māori King from 2006 until his death in 2024. He he was the eldest son of the previous Māori monarch, Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu, and was announced as her successor and crowned on the the final day of her funeral. During the funeral, Māori elders asked three times: ‘Ko Tuheitia hei Kingi?’ (should Tuheitia be King?) and three times the people present responded, ‘Ae’ (yes). With that Tuheitia was anointed as the seventh Māori monarch. Anaru Tamihana used the same bible his ancestor Wiremu Tamihana had placed on Potatau’s head in 1859. [Source: Wikipedia, New Zealand government]

King Tuheitia was truck-driver-turned-royal. Born Tūheitia Paki in the North Island town of Huntly, he was the son of Whatumoana Paki (1926–2011) and Queen Te Atairangikaahu (1931–2006). He was educated at Rakaumanga School in Huntly, Southwell School in Hamilton and St. Stephen's College in Bombay, south of Auckland, New Zealand. He had five sisters. He was married to Te Atawhai. and they had three children: Whatumoana, Korotangi, and Nga wai hono i te po.

During his reign King Tuheitia visited the United Nations, met Pope Francis at the Vatican and represented a New Zealand delegation at the Olympic games in Paris. In March 2024, he made international headlines with an impassioned call for whales to be granted the same legal rights as people. He wanted the marine mammals to have inherent rights, such as having a healthy environment, to allow the restoration of their populations. [Source Ryland James, AFP, August 30, 2024]

King Tuheitiacampaigned to reduce high rates of Indigenous incarceration. In January 2024, Tuheitia hosted more than 10,000 Māori for talks on how to respond to government plans to cancel reforms that were seen by many indigenous people as undermining their rights. Tuheitia and his wife Atawhai met with then-Prince Charles, prince of Wales, and Camilla, duchess of Cornwall, on November 8, 2015. “I had the greatest pleasure of knowing Kiingi Tuheitia for decades,” Charles said. “He was deeply committed to forging a strong future for Māori and New Zealand founded upon culture, traditions and healing, which he carried out with wisdom and compassion.” [Source Hamdi Alkhshali and Kathleen Magramo, CNN, August 30, 2024]

King Tuheitia spoke publicly only once a year, at the annual celebrations in Ngāruawāhia of his coronation. He suffered ill health in 2013 and announced that he was establishing Te Kaunihera a te Kiingi (the King's Council) and deputising his elder son Whatumoana to act on his behalf. Tūheitia later fell out with Whatumoana after the latter married Rangimarie Tahana in June 2022. In response, the Office of the Kīngitanga publicly denounced Whatumoana and Tahana's wedding and stripped Whatumoana of his royal title. In 2013, Tūheitia also announced that his second-born son Korotangi would not succeed him as King due to concerns about his readiness. Korotangi was subsequently convicted of drink-driving offending in 2014 and assaulting his girlfriend in 2020. Following Tūheitia's death in late August 2024, his daughter Nga wai hono i te po succeeded him as Māori Queen. [Source: Wikipedia]

King Tuheitia’s Funeral

King Tuheitia died in August 2024 days after heart surgery and celebrations marking the 18th anniversary of his coronation. He was laid in state for six days, after which he was carried down the Waikato River as part of a flotilla of four war canoes, each powered by more than a dozen rowers. His funerary procession passed throngs of onlookers camped on the riverbanks, before stopping at the foot of sacred Mount Taupiri. From there, three rugby teams acted as pallbearers, shepherding his coffin up steep slopes to the summit and the final resting place of Māori royals. [Source AFP, September 5, 2024]

The death of Kiingi Tuheitia is a moment of great sadness," Māori Spokesman Rahui Papa said in a statement. "A chief who has passed to the great beyond. Rest in love." Tens of thousands of Indigenous citizens and "Pakeha" — those of European ancestry — visited to pay respects, mourn and celebrate New Zealand's rich Māori heritage. Among them was Auckland-based Darrio Penetito-Hemara, who told AFP the king had united "many people across New Zealand who don't often see eye-to-eye". The king leaves a legacy forged "through respect, through aroha (love)", Penetito-Hemara said. "

Women carried wreaths of kawakawa leaves on their heads and were cloaked in patterned shawls. Some prayed gently as they placed bouquets of flowers. Many were marked with facial tattoos — an indelible statement of pride in their Māori heritage. They passed under an ochre-red archway, ornately carved with beaked figures, and into the ceremonial grounds. Inside, leaders sang songs of bereavement — the dirges and polyphonic melodies that have marked Māori funerals for generations.[Source Ryland James, AFP, August 30, 2024]

New Zealand Prime Minister Christopher Luxon ordered flags on government and public buildings to be flown at half-staff and said the country would mourn the king’s death. “His unwavering commitment to his people and his tireless efforts to uphold the values and traditions of Kiingitanga have left an indelible mark on our nation,” he said in a statement. Former Prime Minster Jacinda Ardern described Tuheitia as an advocate for Māori people, as well as for fairness, justice and prosperity. [Source Hamdi Alkhshali and Kathleen Magramo, CNN, August 30, 2024]

Queen Nga Wai Becomes the New Māori Monarch in 2024

In September 2024, New Zealand's Māori chiefs anointed a 27-year-old Nga Wai hono i te po Paki as the new Māori queen, a surprise move applauded as a symbol of change for the Māori community. She was cheered by thousands as she ascended a high-backed wooden throne during an elaborate ceremony on the country's North Island. Nga Wai is the youngest daughter of King Tuheitia Pootatau Te Wherowhero VII,who died a few days earlier. AFP reported: After being elected by a council of chiefs, Nga Wai was ushered to the throne by a phalanx of bare-chested and tattooed men bearing ceremonial weapons — who chanted, screamed and shouted in acclamation. The queen, wearing a wreath of leaves, a cloak and a whalebone necklace, sat beside her father's coffin as emotive rites, prayers and chants were performed. [Source AFP, September 5, 2024]

As the king's only daughter and his youngest child, Queen Nga Wai was considered an outside choice to become his successor.One of her two elder brothers had taken on many ceremonial duties during their father's periods of ill health and had been widely tipped to take over. "It is certainly a break from traditional Māori leadership appointments which tend to succeed to the eldest child, usually a male," Māori cultural advisor Karaitiana Taiuru told AFP.

Taiuru said it was a "privilege" to witness a young Māori woman become queen, particularly given the ageing leadership and mounting challenges faced by the community. "The Māori world has been yearning for younger leadership to guide us in the new world of AI, genetic modification, global warming and in a time of many other social changes that question and threaten us and Indigenous Peoples of New Zealand," he said. "These challenges require a new and younger generation to lead us." New Zealand's Prime Minister Christopher Luxon welcomed Queen Nga Wai in a statement, saying she "carries forward the mantle of leadership left by her father". "The path ahead is illuminated by the great legacy of Kiingi Tuheitia," he said.

Queen Nga Wai is the eighth Māori monarch and the second queen. Her grandmother is Queen Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu. The new queen studied the Māori language and customary law at New Zealand's Waikato University. She also taught "kapa haka" performing arts to children To mark the anniversary of the king's coronation in 2016, she received a traditional Māori "moko" tattoo on her chin.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, New Zealand Tourism Board, New Zealand Herald, New Zealand government, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Live Science, Natural History magazine, New Zealand Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Culture Shock! New Zealand, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated October 2025