Home | Category: Animals / Birds, Crocodiles, Snakes and Reptiles

CASSOWARIES AND HUMANS

Cassowaries that live close to humans, feed on crops and other human foods. Some get used to hand outs and being feed. These birds are more vulnerable than untame birds. They approach too close to cars and dogs. Cassowaries have been traded for hundreds of years. Tribal people have traditionally valued cassowaries for their feathers and dark meat and hunted them with dogs. Eggs are valuable, and bring high prices because it is difficult to find nests. In New Guinea cassowaries may be raised in captivity and fed until they are large enough to sell for food or trade. The large birds have also been featured in traditional religious beliefs and rituals and viewed as a mother figure in legends. The Maring people of Kundagai sacrificed dwarf cassowaries in certain rituals. The Kalam people considered themselves related to cassowaries, and did not classify them as birds, but as kin. Consequently, they use the Pandanus register of the Kalam language when eating cassowary meat. [Source: Danielle Cholewiak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The Asmat and other people in New Guinea made ceremonial daggers from cassowary bones. Bone daggers were once widespread in New Guinea. Their purpose was both symbolic and utilitarian; they functioned as objects of artistic expression with the primary function of stabbing and killing people at close quarters. Most daggers were shaped from the tibiotarsus of cassowaries, but daggers were also shaped from the femora of respected men.

Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: The clear individuality of cassowaries, together with their size and the fact that they do not fly, makes them strangely humanlike: They move like people, they are people-size, and they are easy to tell apart. Because of this, it’s common for people to give them names — such as Crinklecut, Big Bertha, or Dad. It might also explain why they have long figured in the mythologies of rain forest tribes. Some believe that cassowaries are cousins of humans; others, that they are people who have been reincarnated; still others, that humans were created from the feathers of a female. However, unlike in humans, males do all the child care — they sit on the eggs, and look after the chicks for nine months or more — so they also inspire envy. “I’m coming back as a female cassowary!” one mother of five told me. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

Asmat cassowary bone dagger

I’m in the Daintree, the most intact piece of remaining forest. I’m standing by a fig tree, hoping to see Crinklecut — a young male — and his two chicks. Crinklecut’s territory overlaps that of Big Bertha, an enormous and regal female that is probably the chicks’ mother. A human family lives here too, with three children, plus a giant green tree frog that’s moved into the kitchen and lives in a frying pan. Suddenly the youngest of the children comes tearing through the trees to tell me that Crinklecut and his chicks are on their way to a nearby creek. As I come within sight of them, Crinklecut stretches up to his full height and looks at me. Then he and his chicks stroll off, into the dusk.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CASSOWARIES: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN CASSOWARIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

CASSOWARIES OF NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, WHERE THEY LIVE, WHAT THEY'RE LIKE ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

EMUS AND HUMANS: MEAT, OIL, RANCHING AND WARS ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOAS: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION, EXTINCTION, DE-EXTINCTION? ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOA SPECIES: GIANT, SMALL AND HEAVY-FOOTED ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS OF AUSTRALIA: COMMON, UNUSUAL AND ENDANGERED SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOWERBIRDS: BOWERS, TYPES, DECORATIONS, COURTSHIP DISPLAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOWERBIRD SPECIES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

LYREBIRDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

KOOKABURRAS: CHARACTERISTICS, LAUGHING, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PARROTS OF AUSTRALIA-NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, COLORS, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

Cassowaries Raised by Humans 18,000 Years Ago — One of First Domesticated Animals?

In September 2021, in a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, scientists said that cassowaries were raised by humans 18,000 years ago based on the fact that cassowary egg shells in New Guinea dating to that time had signs that the bird were being domesticated. The scientists said people in New Guinea may have reared cassowary chicks to near-adulthood — potentially the earliest known example of humans managing avian breeding. “This is thousands of years before domestication of the chicken,” said Kristina Douglass, an archaeologist at Penn State University and lead author on the study.

Human–cassowary interactions in highland Papua New Guinea:: A) Endemic fruit forming key components of cassowary diet; B) hunters butchering a carcass of a Dwarf Cassowary; C) man wearing headdress including cassowary feathers; D) juvenile cassowary being reared in a village in highland PNG; E) adult male cassowary captivity in a village in highland PNG; and F) man wearing a cassowary quill nose ornament and an armband with a cassowary bone dagger, From PNAS, Kristina Douglass, Penn State University, Max Planck Institute

Asher Elbein wrote in the New York Times: The first people arrived on New Guinea at least 42,000 years ago. Those settlers found rain forests stalked by large, irritable, razor-footed cassowaries — and eventually worked out how to put them to use. During excavations of rock shelter sites in the island’s eastern highlands, Susan Bulmer, an archaeologist from New Zealand, collected artifacts and bird remains that ended up at the National Museum and Art Gallery of Papua New Guinea. Among those remains were 1,019 fragments of cassowary eggshell, dated to 18,000 to 6,000 years ago, likely originating from wild cassowary nests.

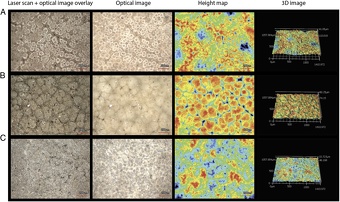

What were the people of the rock shelters doing with the eggs? Dr. Douglass and her colleagues scanned the shells with three-dimensional laser microscopes. Using statistical modeling, comparisons with modern ostrich eggs and careful eyeballing of the shells’ microstructures, they were able to work out how far along each egg had been before hatching. Some eggs — early in development — showed burn patterns, suggesting they’d been cooked. But a large number of fragments — particularly those from around 11,000 to 9,000 years ago — came from almost fully developed eggs. And while people might have been eating the embryos, Dr. Douglass said, “there’s a great possibility that people were hatching those eggs and rearing cassowary chicks.”

To support this claim, she points to some Indigenous groups on the island still raise cassowary chicks from eggs taken out of wild nests. Hatchlings imprint on humans easily and are relatively manageable. (It’s only once they reach adulthood that the danger begins.) While collecting eggs and raising hatchlings is an early step in domestication, it’s unlikely that cassowaries — fairly intractable, as birds go — were ever fully bred in the manner of chickens, which were domesticated 8,000 years ago. But if New Guinea’s early inhabitants hand-reared cassowaries, they would have been some of the earliest-known humans to systematically tame birds, the team concluded. “These findings might radically alter the known timelines and geographies of domestication that tend to be the most widely understood and taught,” said Megan Hicks, an archaeologist at Hunter College in New York. “Where mammals are the best-known early cases (dogs and bezoar ibex), we now know that we need to be paying closer attention to human interactions with avian species.”

Images rendered through high-resolution laser microscopy scanning of cassowary eggshell interior surfaces: A) sample displaying light weathering and clearly defined pitting of mammillary cones; B) sample displaying medium-light weathering and no pitting (prepitting stage; and C) sample displaying extreme weathering, From PNAS, Kristina Douglass, Penn State University, Max Planck Institute

The eggshells carry another interesting implication. Based on the patterns in the eggs, the team suggests that people deliberately harvested eggs within a narrow window of days late in the incubation period. This isn’t easy: Cassowary nests are often quite difficult to find and guarded by unforgiving males, and the eggs have an incubation period of about 50 days. In order to fetch cassowary eggs at a consistent level of development — whether to eat them or hatch them — the ancient New Guineans had to know specifically when and where cassowaries were nesting, Dr. Douglass said. That precision implies sophisticated knowledge — even management — of cassowary movements. “It suggests that people who are in foraging communities have this really intimate knowledge of the environment and can thus shape it in ways we hadn’t imagined,” Dr. Douglass said.

April M. Beisaw, chair of anthropology at Vassar College, said it was “an excellent example of how the smallest and most fragile remainders of the past can provide evidence of important cultural practices. The techniques described can be used in other places to further develop our understanding of how important birds have been to humans, long before the domestication of chickens.”

Mission Beach, Queensland — Cassowary Town

Brendan Borrell wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Ripe fruit plunks to the ground and rolls to the road at my left. That instant, the cassowary bursts from a tangle of ferns outside Clump Mountain National Park near Mission Beach, Australia. The bird's sharp beak is pointed roughly at my neck. Her eyes bulge. She probably weighs about 140 pounds, and as she thumps past me her red wattles swing to and fro and her black feathers give off an almost menacing shimmer. Local residents call her Barbara, but somehow the name doesn't fit the creature in front of me. She looks like a giant, prehistoric turkey — a turkey, however, that could disembowel me with a swipe of its nearly five-inch claws. Luckily, she just wants the mango, which she scoops up whole and mashes with her beak. [Source: Brendan Borrell, Smithsonian magazine, October 2008]

In Mission Beach (pop. 992), two hours south of Cairns, cassowaries have come out of the forest, cruising the streets and looking, it seems, for trouble. They peck at bedroom windows, chase cars and tangle with pet terriers. Townspeople are divided over what to do about the invasion. Many want the birds back in the forest. But others enjoy feeding them, even though that's against the law. They claim that the birds need the handouts: a 15-year drought, a building boom and Cyclone Larry in 2006 wiped out many of the area's native fruit trees, which were prime cassowary food. One woman told me she spends $20 per week on bananas and watermelons for a pair of local birds named Romeo and Mario. "I feed them," she said. "I always have and I always will."

Biologists say she's not doing the birds a favor. "A fed bird is a dead bird," the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service insists on posters and brochures, underscoring the idea that luring the birds into town endangers them. Since the cyclone, some 20 cassowaries, out of a local population of perhaps 100, have died after being hit by cars or attacked by dogs. Wildlife wardens — clad in chain-saw chaps and groin protectors and wielding giant nets — regularly transport problem cassowaries to more suitable habitat.

To see how life in the cul-de-sacs of Mission Beach has affected the largest native land animal in northern Australia, I visited the Garners Beach cassowary rehabilitation facility five miles north of town. Steve Garrad, a conservation officer for the Australian Rainforest Foundation, was wearing a dirt-streaked khaki outfit and a pair of gaiters to ward off the region's infernal leeches. We entered a pen where a knee-high cassowary chick was zipping along like a teenager on a skateboard. Rocky had been plucked from a dog's mouth in South Mission Beach a few months earlier. Cassowary chicks are striped for camouflage, and Rocky seemed to vanish in the shady enclosure. We finally cornered him near an artificial pond.

At the rehab center, Rocky retreated back into the shadows. He has made a full recovery after his encounter with the dog. Adult male cassowaries will adopt orphaned chicks, and Garrad hoped to find a surrogate dad in the wild that would rear Rocky. Garrad said it's sometimes hard to send the little ones off to an uncertain fate, but the best thing for wildlife is to return to the wild.

Beachgoers Stunned When a Cassowary Emerges from the Surf

In October 2023, people at a popular beach in Moresby Range, Queensland when a cassowary emerged from a swim in the ocean. The Miami Herald reported: Onlookers spotted a creature swimming toward the Bingil Bay Campground, the Queensland Department of Environment and Science said. At first, they thought it was a turtle or a shark. As the animal reached the shore, its identity became clear. It was a juvenile cassowary, wildlife officials said. Bingil Bay is near Mission Beach about 160 kilometers (100 miles) south of Cairns. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, November 14, 2023]

“Cassowaries can swim and will take to the water to cross from one side of a river to the other, or if they feel threatened by domestic dogs or another cassowary through a territorial dispute,” Stephen Clough, a wildlife officer with the Queensland Department of Environment and Science, said in the release.“We’re not sure how long this animal was in the water or why it went for a swim but the footage is astonishing,” Clough said.

The campground’s host, Nikita McDowell, filmed the cassowary’s “unexpected ocean swim,” officials said. Video footage shared on Facebook by nine News shows the large bird bobbing along the waves. From afar, only its head and neck are visible, giving the impression of a periscope. As the bird reached the shore, the rest of its brown-black body became visible.

The cassowary appears to look at the camera several times, video footage shows. “It just floated to shore until it reached the level where its feet could touch the ground,” McDowell told the Australian Broadcasting Corp. “It must’ve been exhausted as it stood in the shade beneath a tree with its legs shaking for about half an hour,” McDowell said in the release. “I went to make a coffee and when I returned, it was gone.I knew it wasn’t going to have the energy to attack me or anything.“I am just so happy it’s moved on and safe and healthy,”

Cassowary Conservation

There’s an estimated 1,500 to 4,000 cassowaries remaining in Queensland. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List but doesn’t mean they are in the clear. Threats include habitat loss, vehicle strikes and domestic dog attacks. The Wet Tropics Management Authority’s robust conservation plan to keep cassowaries includes protecting habitats and migration corridors and educating locals on cassowary behavior. endangered.

Studying cassowaries and figuring out exactly how many there are because they are difficult to find and observing their behavior in the rain forest is difficult. They live alone, in dense forests. Attempts have been made to estimate numbers based on DNA taken from droppings and photographs of individuals coming to emergency feeding stations set up after cyclones. It is not clear if populations are rising or falling — or how endangered they are.

Brendan Borrell wrote in Smithsonian magazine: While programs to protect koalas draw in millions of dollars in donations ,cassowary conservation just squeaks by. The ruggedly independent folk of Queensland feel a bond with their local emblem of biodiversity — everything from stuffed toys to cassowary-themed wind chimes can be purchased along the Cassowary Coast — perhaps out of respect for a flightless creature that's able to eke out an existence despite suffocating heat and devastating storms. [Source: Brendan Borrell, Smithsonian magazine, October 2008]

Forests occupied by cassowaries have been cute to make way for housing developments. Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: Some locals are trying to prevent all this — clubbing together to buy land to create nature preserves, replanting rain forest trees on cleared land, and lobbying farmers not to cut down forest. The hope is to link forest fragments, so that young cassowaries looking for territories can move from one fragment to another without having to cross the open fields of sugarcane plantations, or big highways. For the cassowary depends on the forest even more than the forest depends on the cassowary. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

Cassowaries — The World’s Most Dangerous Birds

Solitary cassowaries usually quickly retreat and crash through the forest with their feet hitting the ground like drum beats when threatened. Males protecting eggs are another story. They will fight rather than retreat. Cassowaries attack with their feet. A single blow from cassowary feet can rip open a man's stomach. Humans have been killed by such attacks, as males can be extremely aggressive when protecting nests or young.

Cassowaries fight with their beaks and wings and particularly their legs and claws. They have three toes on each foot. The long-nailed inner claw can be used as a lethal weapon. The claws can up to 12.5 centimeters) (5 inches) long. Male cassowaries use their razor-sharp spikes on both inside toes. They can inflict great damage with these spikes and their powerful kick.

Cassowaries have been ranked as the world's most dangerous bird by the Guinness World Records based on recorded numbers of attacks on people and the severity of injuries inflicted. People in countries where they live are well aware of the hazards of approaching a cassowary and even military troops arriving in New Guinea in World War II were warned to give them a wide berth. In his 1958 book Living Birds of the World, ornithologist Ernest Thomas Gilliard wrote: “The inner or second of the three toes is fitted with a long, straight, murderous nail which can sever an arm or eviscerate an abdomen with ease. There are many records of natives being killed by this bird.”

Documented cases of aggression from the cassowary have been used to study their behaviour. Many cases involve attacks on domestic dogs. Several attacks were on humans that had been feeding the birds for some time and had developed a sense of trust. Rarer were cases involving attacks in self defense when people were attempting to kill or injure the cassowaries. Like all animals, they should be treated with respect and caution. Feeding wild animals can have immediate and disastrous consequences. [Source: Rumble, November 13, 2020]

Cassowary Attacks on Humans

Brendan Borrell wrote in Smithsonian magazine: A cassowary can charge up to 50 kilometers an hour (30 miles an hour) and leap more than a meter (three feet in the air). On each foot are three claws — one slightly curved like a scimitar, the other two straight as daggers — that are so sharp New Guinea tribesmen slide them over spear points. [Source: Brendan Borrell, Smithsonian magazine, October 2008]

A 2003 historical study recorded 221 cassowary attacks, of which 150 had been against humans. Of these 75 percent had been from cassowaries that had been fed by people, 71 percent of the time the bird had chased or charged the victim, and 15 percent of the time they kicked. Of the attacks, 73 percent involved the birds expecting or snatching food, 5 percent involved defending their natural food sources, 15 percent involved defending themselves, and 7 percent involved defending their chicks or eggs. Only one human death was reported among those 150 attacks. [Source: Wikipedia]

In April 2019, kicks from a captive cassowary mortally wounded a 75-year-old Florida man. The man owned the cassowary and who had it. He was apparently clawed to death after he fell to the ground.

In 1926, 16-year-old Phillip McLean, died after his throat was punctured in cassowary attack on his Queensland ranch in 1926. The first documented human death caused by a cassowary was on April 6, 1926. In Australia, McClean and his 13-year-old brother, 13, came across a cassowary and decided to try to kill it by striking it with clubs. The bird kicked the younger boy, who fell and ran away as his older brother struck the bird. The older McClean then tripped and fell to the ground. While he was on the ground, the cassowary kicked him in the neck, opening a 1.25-centimeter (0.49 inch) wound that severed his jugular vein. The boy died of his injuries shortly thereafter. Since then there have many close calls since: people have had ribs broken, legs cracked and flesh gashed.

Most of the six attacks on humans in Australia between 1990 and 2000 were hikers trying to feed cassowaries. In February 2001, an employee at the San Francisco Zoo was injured by a cassowary. The bird tore into his leg with its powerful claws. "It's not totally certain what happened," general curator David Robinett told the San Francisco Chronicle. "We'll look at what happened and why and take steps to make sure it doesn't happen again." Doctors at Seton Medical Center in Daly City treated the victim, and released him several hours later. The attack occurred inside the cassowary exhibit at about 3:30 p.m. Robinett said it was unusual for employees to be inside the cage with the cassowary, a 5-year-old male that came to the zoo from an American hatchery in 1997. "These birds are very territorial, and generally we're not inside the enclosure with them," Robinett said. "They (males) tend to want to protect their territory." Robinett said the animal responsible for yesterday's incident had no history of aggression.[Source: Chuck Squatriglia, San Francisco Chronicle, February 16, 2001]

Some people attacked by cassowaries seem to be asking for it. Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: Adding to their mystique, cassowaries have a reputation for being dangerous. And certainly if you keep them in a pen and rush at them with a rake — which, judging by videos posted on YouTube, some people do — they are. They are big, they have claws and a powerful kick, and they will use them. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, September 2013]

If cassowaries come to associate humans with food handouts, they can become aggressive and demanding. If you get close to a male with young chicks, he may charge you in an attempt to protect them. If you try to catch or kill a cassowary, it may fight back — and could well get the better of you. They sometimes kill dogs. But let’s get this straight. Left to themselves and treated with respect, cassowaries are shy, peaceable, and harmless.

Elderly Man Attacked by Cassowary in His Backyard

In April 2025, am elderly man in Cardell, Queensland was rushed to hospital after being attcked by a cassowary in his backyard looking for food. Simon Sage wrote in The Cool Down: A man in his 70s was relaxing in his backyard when a cassowary found its way in and attacked, leaving him bleeding from the back of his thigh. He was taken to a hospital in nearby Tully, treated, and released shortly thereafter. Agents from the Department of Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation were unable to track down the animal afterward, despite other encounters in the vicinity. [Source: Simon Sage, The Cool Down, April 24, 2025]

Local experts suggest that cassowaries become comfortable around people only after receiving food from them. This leads to a shift in behavior where wild animals approach humans more routinely with the expectation of food, contributing to an increase in more dangerous encounters — a pattern observed in other animal species, such as bears in North America. "They will come into people's yards and look for food," said veterinarian Graham Lauridsen, per the ABC. "They become less scared of people and then they'll approach people and then dramas can happen."

Lauridsen also said that recent floods in the encompassing Cassowary Coast region were likely a contributing factor. There is broad consensus among wildlife experts that feeding wild animals leads to negative and sometimes harmful outcomes. Food sources can significantly alter animal behavior, and the closer they are to humans, the greater the likelihood of injury.

Mother and Child Narrowly Escape 'Close Encounter' with a Cassowary

In May 2025, a mother and her child had a close call with a cassowary and their narrow escape was caught on security cameras. Bailey Richards wrote in People: In the surveillance footage, the mom and her child walk up to a door in Mission Beach. The kid picks up his pace to a run after spotting two cassowaries behind them. The mother, who is walking ahead of her child, notices the birds and holds the door open for the kid as he runs inside. The two cassowaries follow closely behind but don't make it in. The birds slow down after realizing the human duo had made it inside, but they still approach the now-closed door, the footage shows. [Source: Bailey Richards, People, June 26, 2025]

The birds — one tall and one much smaller — were "a habituated male cassowary and his chick," the Queensland department said, adding that they were "approaching a home in the hopes of being fed." This hope is generated by human interference, which is why authorities "are urging people to avoid unlawfully feeding wildlife," particularly cassowaries.

"This incident is one of several cassowary interactions in the area which are linked to unlawful feeding,"wildlife ranger Jeff Lewis said in a statement. "Thankfully, the mother and child were able to get inside to safety, but it's an important reminder not to interfere with wildlife."

Avoiding Cassowary Attacks

If you encounter a hostile cassowary you are advised to hide behind a tree or something else.. If you don’t threaten a cassowary, unless it is expecting food, it will probably walk away from you."They're most active at twilight, have a claw that rivals Freddy Krueger's, and are one of the few bird species that have killed humans," the WWF says. Don’t run. Both cassowary fatalities occurred to people who had fallen to the ground.

Don’t feed cassowaries. Queensland wildlife ranger Jeff Lewis said: "Local wildlife rangers have been warning people of the risks, installing signage and providing education, but the unlawful feeding persists. When cassowaries associate humans with food, they can become impatient and aggressive, particularly when accompanied by chicks." [Source: Bailey Richards, People, June 26, 2025]

The Queensland Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation advises people to "never approach cassowaries," especially not chicks, as "male cassowaries will defend them." People living in cassowary-populated areas should also slow down when driving, but not stop to look at the birds (if they are on the road). Dogs living near cassowary habitats should also be leashed or kept behind a fence.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025