Home | Category: Animals / Marsupials

EXTINCTION OF THE TASMANIAN WOLF

The last known Tasmanian wolf died on September 7, 1936 at a zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. Intensive hunting is generally blamed for the extinction but other factors contributed, such disease, the introduction of non-native species, habitat loss, human encroachment into their habitat and climate change. Competition from domestic dogs, hunting by European sheep ranchers, and an epidemic of distemper have all been blamed for the decline of Tasmanian wolves. [Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); Anay Park, Smithsonian magazine, August 1988]

Tasmanian wolves — (Thylacinus cynocephalus), officially called thylacines and also known as Tasmanian tigers — died out in New Guinea and mainland Australia around 3,600 to 3,200 years ago, way before the arrival of Europeans, possibly because of the introduction of dingo, whose earliest record dates to around the same time, but which never reached Tasmania. Trouble for Tasmanian wolves began in the 1830s when they began to regularly feed on sheep, particularly young lambs. Bounties were offered for killing the animal and their pelts even became sought after in England. At least 4,800 Tasmanian wolves were killed between 1878 and 1909 and nearly 3,500 pelts were shipped to London during that same period. By 1917, when Tasmania put a pair of Tasmanian wolves on its coat of arms, real ones were rarely seen. In 1909 bounties were only paid on two animals.

Tasmania was first "discovered" by Europeans in 1642, by the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman. The first English settlers in Tasmania arrived in 1803 and spread across the island, whose human and animal inhabitants had lived in isolation for more than 10,000 years. The first record of a Tasmanian wolf being killed was in 1805, but only four sightings of the animals were reported between 1803 and 1820. In the 19th century they were called zebra wolves and people believed they brought bad luck. They were killed at every opportunity and their heads were often nailed to barn doors. The last confirmed sighting of a Tasmanian wolf in the wild was in 1930. Tasmanian wolves were declared a protected species in 1936, the same year it became extinct [Source: Anay Park, Smithsonian magazine, August 1988]

Many Tasmanian wolves were killed because they were blamed for preying on sheep and other livestock. By the turn of the 20th century their numbers had sharply declined. In 1906, Tasmanian government paid out 58 bounties to trappers and hunters who presented the bodies of Tasmanian wolves. In 1907, bounties were paid for 42 carcasses. In 1908, the number was 17. In 1909 there were two. The following year there were none, the same the year after that, or ever again. [Source: Brooke Jarvis, The New Yorker, June 25, 2018]

DNA taken from the hair of two extinct Tasmanian wolves suggests that they were too inbred to survive as a species, researchers reported in January 2009 in journal Genome Research. According to Reuters: The researchers used the method they used to study the DNA from extinct woolly mammoths’ hair to get a good comparison of the gene sequences from Tasmanian wolves. The research team pulled and sequenced DNA from the hair of a male Tasmanian wolves brought to the U.S. National Zoo in Washington in 1902 and a female that died in the London Zoo in 1893. “What I find amazing is that the two specimens are so similar,” said Dr. Anders Gotherstrom of Uppsala University in Sweden, who worked on the study. “There is very little genetic variation between them.” [Source: Reuters, January 13, 2009]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TASMANIAN WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVIL CONSERVATION: HUMANS AND THE DEADLY DISEASE RAVAGING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com

DASYURIDS AND DASYUROMORPHS (MARSUPIAL CARNIVORES) ioa.factsanddetails.com

NUMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLL SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SMALL MARSUPIAL CARNIVORE SPECIES: MULGARA, DIBBLERS, KULTARRS, NINGAUI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DUNNARTS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLANIGALES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANTECHINUSES: SPECIES, FALSE ONES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUICIDAL MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Last Tasmanian Wolves

The last known Tasmanian wolf, a female died on September 7, 1936 in the private zoo of Mary Grant Roberts in Hobart, Tasmania. The animal, a female, had been captured by Elias Churchill with a snare trap and was sold to the zoo in May 1936. [Source: Wikipedia]

Brooke Jarvis wrote in The New Yorker: By 1930, when a farmer named Wilf Batty shot what was later recognized as the last Tasmanian wolf killed in the wild, it was such a curiosity that people came from all over to look at the body. The last animal in captivity died of exposure in 1936, at a zoo in Hobart, after being locked out of its shelter on a cold night. The Hobart city council noted the death at a meeting the following week, and authorized thirty pounds to fund the purchase of a replacement. The minutes of the meeting include a postscript to the demise of the species: two months earlier, it had been “added to the list of wholly protected animals in Tasmania.” [Source: Brooke Jarvis, The New Yorker, June 25, 2018]

It has been widely reported that the last Tasmanian wolf was a female named Benjamin. The story goes that he was one of three cubs, whom, with their mother, were captured and displayed at the Hobart Zoo. Benjamin was the last survivor of these cubs and lived to a record age of 12.6 years old. She has been recognized as the oldest living Tasmanian wolf and the last. Some of this may be true but Tasmanian wolf called Benjamin was not the last one. [Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The last known film footage of a living Tasmanian wolf is 45-second, black-and-white clip showing a Tasmanian wolf in its enclosure in 1933. The footage was shot by naturalist David Fleay who was bitten in the rear by the animal while shooting the film. The footage shows the Tasmanian wolf walking around the perimeter of its enclosure, yawning, sitting down, sniffing the air, scratching itself like a dog and lying down.

The remains of the last Tasmanian wolf were given to a local museum after it died and then were lost until they were rediscovered in cupboard in the museum in 2021. The BBC reported: The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery lost track of the remains, and they were believed to have been thrown out. Research discovered they were at the museum all along — preserved but not properly catalogued. "For years, many museum curators and researchers searched for its remains without success, as no Tasmanian wolves material dating from 1936 had been recorded," said Robert Paddle, who published a book in 2000 on the extinction of the species.

"It was assumed its body had been discarded." But he and one of the museum's curators found an unpublished taxidermist's report, prompting a review of the museum's collections. They found the missing female specimen in a cupboard in the museum's education department. It had been taken around Australia as a travelling exhibit but staff were unaware it was the last Tasmanian wolves, curator Kathryn Medlock told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. "It was chosen because it was the best skin in the collection," she said. "At that time they thought there were still animals out in the bush." The skin and skeleton are now on display at the museum in Hobart. [Source: Tiffanie Turnbull, BBC, December 5, 2022]

Sightings of Tasmanian Wolves

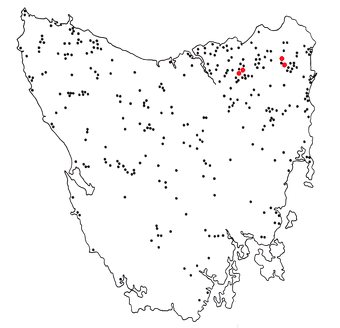

Map of the locations of reported sightings of Tasmanian wolves between 1936 and 1980 in Tasmania: one reported sighting (black);

five reported sightings (red)

Sightings are Tasmanian wolves have periodically been reported and continue to this day. There were more 300 sightings of Tasmanian wolves between 1936 and 1990. In 1970, six respected citizens all say they saw one a road between Scottsdale and Launceston, Tasmania. In 1977 two policemen say they had to break hard to avoid hitting one. And in 1982 a ranger with the Tasman National Park and Wildlife service (TNPWS) said he spotted one with his headlights only six meters (20 feet away). The ranger tried to follow the animal’s tracks but they were obliterated by the rain. True believers of such sightings point to the Leadbetter possum believed to be extinct for 50 years was rediscovered in 1961

Brooke Jarvis wrote in The New Yorker: Long after the accepted date of extinction, Tasmanians kept reporting that they’d seen the animal. There were hundreds of officially recorded sightings, plus many more that remained unofficial, spanning decades. Wolves were said to dart across roads, hopping “like a dog with sore feet,” or to follow people walking in the bush, yipping. A hotel housekeeper named Deb Flowers told me that, as a child, in the nineteen-sixties, she spent a day by the Arm River watching a whole den of striped animals with her grandfather, learning only later, in school, that they were considered extinct. [Source: Brooke Jarvis, The New Yorker, June 25, 2018]

In 1982, an experienced park ranger, doing surveys near the northwest coast, reported seeing a wolf in the beam of his flashlight; he even had time to count the stripes (there were twelve). “10 A.M. in the morning in broad daylight in short grass,” a man remembered, describing how he and his brother startled a wolf in the nineteen-eighties while hunting rabbits. “We were just sitting there with our guns down and our mouths open.” Once, two separate carloads of people, eight witnesses in all, said that they’d got a close look at a wolf so reluctant to clear the road that they eventually had to drive around it. Another man recalled the time, in 1996, when his wife came home white-faced and wide-eyed. “I’ve seen something I shouldn’t have seen,” she said. “Did you see a murder?” he asked....“No,” she replied. “I’ve seen a wolf.”

As reports accumulated, the state handed out a footprint-identification guide and gave wildlife officials boxes marked “Thylacine Response Kit” to keep in their work vehicles should they need to gather evidence, such as plaster casts of paw prints. Expeditions to find the rumored survivors were mounted—some by the government, some by private explorers, one by the World Wildlife Fund. They were hindered by the limits of technology, the sheer scale of the Tasmanian wilderness, and the fact that Tasmania’s other major carnivore, the devil, is nature’s near-perfect destroyer of evidence, known to quickly consume every bit of whatever carcasses it finds, down to the hair and the bones. Undeterred, searchers dragged slabs of ham down game trails and baited camera traps with roadkill or live chickens. They collected footprints, while debating what the footprint of a live wolf would look like, since the only examples they had were impressions made from the desiccated paws of museum specimens. They gathered scat and hair samples. They always came back without a definitive answer.

Trudy Richards, a clerk at a farm-supply store with who has no scientific training. searched in forests of Tasmania for Tasmanian wolves for years. Richard C. Paddock wrote in the Los Angeles Times: She put motion-sensor cameras and audio recorders in the forest. She built sand traps to capture a footprint. She trekked through the woods, her camera at the ready. She spent hours on stakeouts... Then, she said, she finally saw one. According to her account, a Tasmanian wolf, as the creature is commonly known, walked into her campsite one winter evening just before midnight. Richards says her camera was out of reach but insists there was no mistaking the animal's distinctive black stripes. [Source: Richard C. Paddock Los Angeles Times, November 21, 2004]

Scientists Say Tasmanian Wolves Might Have Survived into the 1990s

Based on over 1,237 reported Tasmanian wolf sightings in Tasmania from 1910 to 2022, researchers argued in a study published March 18, 2023 in the journal Science of The Total Environment that Tasmanian wolves probably survived until the late 1980s or 1990s and there is a "small chance" they could still be alive today, but others are skeptical.

Sascha Pare wrote in Live Science: The team estimated the reliability of these reports and where Tasmanian wolves could have persisted after 1936. "We used a novel approach to map the geographical pattern of its decline across Tasmania, and to estimate its extinction date after taking account of the many uncertainties," Barry Brook, a professor of environmental sustainability at the University of Tasmania and lead author of the study, told The Australian. Tasmanian wolves may have survived in remote areas until the late 1980s or 1990s, with the earliest date for extinction in the mid-1950s, the researchers suggest. The scientists posit that a few Tasmanian tigers could still be holed up in the state's southwestern wilderness.[Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 12, 2023]

But others are skeptical. "There is no evidence to confirm any of the sightings," Andrew Pask, a professor of epigenetics at the University of Melbourne told Live Science. "One thing that's so interesting about the Tasmanian wolf is how it evolved to look so much like a wolf and so different to other marsupials. Because of this, it is very hard to tell the difference at distance between a Tasmanian wolf and [a] dog and this is likely why we still continue to have so many sightings despite never finding a dead animal or unequivocal picture." If Tasmanian wolves had survived long in the wild, someone would have come across a dead animal, Pask said. Nevertheless, "it would be possible at this time [in 1936] that some animals persisted in the wild," Pask said. "If there were survivors, there were very few."

In the study reports were classified based on credibility. Joshua Rapp Learn wrote in the New York Times: More than half of the reports came from the general public. The team also found spikes of sightings that were probably linked to high-profile Tasmanian wolves news in Australia — what Brook’s team called “recency bias.” Some reports between 1910 and 1937 were of confirmed captures or kills, with the last fully wild photographed kill occurring in 1930. Brook’s team considered another four reports of kills and captures/releases from 1933-1937 legitimate. [Source: Joshua Rapp Learn, New York Times. April 8, 2023]

For the following eight decades, 26 deaths and 16 captures were reported but not verified, as were 271 reports made by people that Brook’s team considered experts: former trappers, outdoorsmen, scientists or officials. These types of high-quality reports from experts peaked in the 1930s and started to fall in the 1940s. The best quality report came from a park officer who saw one in 1982 (See Above). A model based on all these reports reveals Tasmanian wolves likely went extinct between the 1940s and 1970s, with a smaller chance they persisted in remote areas until the 1980s or even the early 2000s.” But “Mooney said that even if Tasmanian wolves did persist past 1936, the likelihood of their still being around shrinks all the time. Someone should have found one by now, given the high levels of roadkill in Tasmania and the increasing use of trail cameras in more remote parts.

Search for Tasmanian Wolves

Locations of Tasmanian wolf sightings in Victoria on the Australian mainland according to the Thylacine Awareness Group of Australia

Critics of Tasmanian wolves sightings compare them to sightseeing of the Loch Ness monster or Big Foot. They say if that Tasmanian still existed they would be reports of attacks on domestic animals like there was in the past. But this has stopped men like Irish born zoologist Eric Guiler who believe Tasmanian wolves still around. In the early 1980s he was given a $55,000 grant by the World Wildlife Fund to attempt to provide scientific proof that Tasmanian wolves still existed. He deployed cameras self-triggering cameras with infrared sensing beams but after turning up nothing he concluded in a 1333 page report that "the probability of Tasmanian wolves survival must now be considered remote.

In 1983, after winning the Sydney-to-Hobart Yacht Race, Ted Turner offered a $100,000 reward for proof of the animal's existence. A tourist entrepreneur named Peter Wrights spent $250,000 and employed helicopters, triggered camera, sound-detecting devises and computers but also came up with nothing. In 2005, a magazine offered 1.25 million Australian dollars. “Like many others living in a world where mystery is an increasingly rare thing,” the editor-in-chief said, “we wanted to believe.” The rewards went unclaimed, but the wolf’s fame grew.

Brooke Jarvis wrote in The New Yorker: Andrew Orchard lives near the northeastern coast of Tasmania, in the same ramshackle farmhouse that his great-grandparents, the first generation of his English family to be born on the Australian island, built in 1906. When I visited Orchard there, in March, he led me past stacks of cardboard boxes filled with bones, skulls, and scat, and then rooted around for a photo album, the kind you’d expect to hold family snapshots. Instead, it contained pictures of the bloody carcasses of Tasmania’s native animals: a wombat with its intestines pulled out, a kangaroo missing its face. “A wolf will always eat the jowls and eyes,” Orchard explained. “All the good organs.” The photos were part of Orchard’s arsenal of evidence against a skeptical world—proof of his fervent belief, shared with many in Tasmania, that the island’s apex predator, an animal most famous for being extinct, is still alive. [Source: Brooke Jarvis, The New Yorker, June 25, 2018]

When Orchard was growing up, his father would tell him stories of having snared one, on his property, many years after the last confirmed animal died. Orchard says that he saw his first wolf when he was eighteen, while duck hunting, and since then so many that he’s lost count. Long before the invention of digital trail cameras, Orchard was out in the bush rigging film cameras to motion sensors, hoping to get a picture of a wolf. He showed me some of the most striking images he’d collected over the decades, sometimes describing teeth and tails and stripes while pointing at what, to my eye, could very well have been shadows or stems. Orchard estimates that he spends five thousand dollars a year just on batteries for his trail cams. The larger costs of his fascination are harder to calculate. “That’s why my wife left me,” he offered at one point, while discussing the habitats wolves like best.

Wolf enthusiasts are quick to bring up Lazarus species—animals that were considered lost but then found—which in Australia include the mountain pygmy possum (known from fossils dating from the Pleistocene and long thought to be extinct, it was found in a ski lodge in 1966); the Adelaide pygmy blue-tongue skink (rediscovered in a snake’s stomach in 1992); and the bridled nailtail wallaby, which was resurrected in 1973, after a fence-builder read about its extinction in a magazine article and told researchers that he knew where some lived. In 2013, a photographer captured seventeen seconds of footage of the night parrot, whose continued existence had been rumored but unproven for almost a century. Sean Dooley, the editor of the magazine BirdLife, called the rediscovery “the bird-watching equivalent of finding Elvis flipping burgers in an outback roadhouse.” The parrots have since been found from one side of the continent to the other. Is it more foolish to chase what may be a figment, or to assume that our planet has no secrets left?

Tasmanian Wolf Searching Clubs

Brooke Jarvis wrote in The New Yorker: In 2018, three men calling themselves the Booth Richardson Wolf Team held a press conference on the eve of Threatened Species Day—which Australia commemorates on the day the Hobart Zoo Tasmanian wolf died—to announce new video footage and images that they said showed the animal. They’d set up cameras after Greg Booth, a woodcutter and a former wolf nonbeliever, said that while walking in the bush two years earlier he had spotted a Tasmanian wolf only three metres away, close enough to see the pouch. The videos were shot from a distance, and grainy, but right away they prompted headlines, from National Geographic to the New York Post. By the time I arrived in Tasmania, this spring, the team had gone to ground. When I reached Greg’s father by phone, he told me that their lawyer had forbidden them from talking to anyone, because they were seeking a buyer for their recording. [Source: Brooke Jarvis, The New Yorker, June 25, 2018]

One of Tasmania’s most prominent wolf-hunting groups, the Tasmanian wolf Research Unit, or T.R.U., looked at the images and pronounced the animal a quoll, a marsupial carnivore that looks vaguely like a weasel. T.R.U., whose logo is a question mark with wolf stripes, has its own Web series and has been featured on Animal Planet. “Every other group is believers, and we’re skeptics, so we’re heretics,” Bill Flowers, one of the group’s three members, told me one day in a café in Devonport, on the northern coast.

Since Flowers began investigating Tasmanian wolf sightings, he has been reading about false memories, false confessions, and the psychology of perception—examples, he told me, of the way “the mind fills in gaps” that reality leaves open. He talked about the unreliability of eyewitness testimony in court cases, and pointed out that many people, after spotting a strange animal, will look it up and retroactively decide that it was a Tasmanian wolf, creating what he calls a “contaminated memory.” It isn’t unusual for an interest in Tasmanian wolves to lead back to the psychology of the humans who see them. “Your brain will justify your investment by defending it,”Nick Mooney, a Tasmanian wildlife expert, told me.

Checking the Veracity of Tasmanian Wolf Sighting Claims

Nick Mooney was a wildlife expert in charge of investigating claimed Tasmanian devil sightings. Mooney interviewed hundreds of people who reported Tasmanian wolves. He found that most either misidentified the creature they saw, lied or were delusional — and that a psychological effect or modified memory might be to blame in some cases. [Source: Joshua Rapp Learn, New York Times. April 8, 2023]

Brooke Jarvis wrote in The New Yorker: In 1982, Mooney was studying raptors and other predators for the state department of wildlife when a colleague, Hans Naarding, reported that he’d seen a Tasmanian wolf. The department had just been involved in the World Wildlife Fund search, which had found no hard proof but, as the official report, by the wildlife scientist Steve Smith, put it, “some cause for hope.” Naarding’s sighting was initially kept secret, a fact that still provides grist for conspiracy theorists. Mooney led the investigation, which took fifteen months; he tried to keep out the nosy public by saying that he was studying eagles.

The search again turned up no concrete evidence, but, from 1982 until 2009, when Mooney retired, he became the point person for wolf sightings. The department developed a special form for recording them, noting the weather, the light source, the distance away, the duration of the sighting, the altitude, and so on. Mooney also recorded his assessment of reliability. Some sightings were obvious hoaxes: a German tourist who took a picture of a historical photo; a man who said that he’d got indisputable proof but, whoops, the camera lurched out of his car and fell into a deep cave (he turned out to be trying to stop a nearby logging project); people who painted stripes on greyhounds. Mooney noticed that people who had repeat sightings also tended to prospect for gold, reflecting an inclination toward optimism that he dubbed Lasseter syndrome, for a mythical gold deposit in central Australia. One man gave Mooney a diary in which he had recorded the hundred or so wolves he believed he’d seen over the years. The first sighting was by far the most credible. Eventually, though, the man would “see sightings in piles of wood on the back lawn while everybody else was having a barbecue,” Mooney said. “What we’re talking about here is the path to obsession. I know people who’ve bankrupted themselves and their family . . . wrecked their life almost, chasing this dream.”

But there were always stories that Mooney couldn’t dismiss. The most compelling came from people who had little or no prior knowledge of the Tasmanian wolf, and yet described, just as old-timers had, an awkward gait and a thick, stiff tail that seemed fused to the spine. There were also the separate groups of people who saw the same thing at the same time. He often had people bring him to the scene, and then would reënact the sighting with a dog, taking his own measurements to test the accuracy of people’s perceptions, their judgment of distance and time.

Searching for the Tasmanian Wolves Outside Tasmania

The sightings of Tasmanian wolves are not just in Tasmania, In 1997, villagers in West Papua, New Guinea in Indonesia claim they saw a Tasmanian wolf eating their chickens and dogs near the Papua New Guinea border. There have also been a fair number of sighting in the southwest Australian mainland.

Brooke Jarvis wrote in The New Yorker: Aboriginal stories place the wolf close to the present, and mainland believers contend that there have been many more sightings — by one count, around 5,000 — reported on the mainland than in Tasmania...Tasmanian wolf lore in western Australia is so extensive that the animal has its own local name, the Nannup wolf. A point of particular debate is the age of a Tasmanian wolf carcass found in a cave on the Nullarbor Plain in 1966, so fresh that it still had an intact tongue, eyeball, and striped fur. Carbon dating indicated that it was in the cave for perhaps four thousand years, essentially mummified by the dry air, but believers argue that the dating was faulty and the animal was only recently dead. [Source: Brooke Jarvis, The New Yorker, June 25, 2018]

To many Tasmanian enthusiasts, mainland sightings are a frustrating embarrassment that threatens to undermine their credibility; they can be as scathing about mainland theorists as total nonbelievers are about them. “Every time a witness on the mainland says, ‘I found a wolf!,’ it looks like they filmed it with a potato and it’s a fox or a dog,” Mike Williams, the panther researcher, told me. He pointed out that sarcoptic mange, a skin disease caused by infected mite bites, is widespread in Australian animals, and can make tails look stiff and fur look stripy.

In 2017, researchers at James Cook University, in Queensland, announced that they would begin looking for the Tasmanian wolf in a remote tropical region on Cape York Peninsula and elsewhere in Far North Queensland, at the northeastern tip of Australia, about as far from Tasmania as you can get and still be in the country. The search, using five hundred and eighty cameras capable of taking twenty thousand photos each, was prompted by sightings from two reputable observers, an experienced outdoorsman and a former park ranger, both of whom believed that they had spotted the animal in the nineteen-eighties but had, in the intervening years, been too embarrassed to tell anyone. “It’s important for scientists to have an open mind,” Sandra Abell, the lead researcher at J.C.U., told me as the hunt was beginning. “Anything’s possible.”

In Adelaide, I met up with Neil Waters, a professional horticulturist, who, on Facebook, started the Tasmanian wolf Awareness Group, for believers in mainland wolves. Waters, who was wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the phrase “May the Stripes Be with You,” told me that he has “a bit more faith in the human condition” than to think that so many people are all deluded or lying. “Narrow-minded approach to life, I call it,” he said. He told me that he also felt a certain ecological responsibility, because his ancestors “were the first white trash to get off a ship, so we’ve been destroying this place for a long time.” His family had been woodcutters, and, for him, becoming a horticulturist was a kind of karmic reparation.

In the dry hills outside the city, we stopped in an area called, appropriately or not, Humbug Scrub, and then picked up Mark Taylor, a musician and a Tasmanian wolf enthusiast who lived nearby. A few months earlier, Taylor said, his son-in-law and grandson had seen what they described as a dog that hopped like a kangaroo, and Taylor was yearning for a sighting of his own. “It’s becoming one of the bigger things in my life,” he said. Anytime we were near dense brush, he would get animated, saying, “There could be a Tasmanian wolf in there right now and we’d never know!” Once, just as he said this, there was movement on a distant hillside and he jumped, only to realize that it was a group of kangaroos. The world felt overripe with possibility.

Four weeks earlier, Waters had left a road-killed kangaroo next to a camera in a place where he had found a lot of mysterious scat containing bones. “Shitloads of shit!” he exulted. Now he and Taylor were going to find out what glimpses of the forest’s private history the camera had recorded. As they walked, Taylor stopped to gather scat samples for a collection that he keeps in his bait freezer for DNA analysis. “My missus hates it,” he said.

The kangaroo was gone, except for some rank fur and a bit of backbone. Waters retrieved the camera from the tree to which he’d strapped it. Taylor was bouncing again. “This is when we hope,” he said. Back at the car, we crouched by the open trunk as Waters removed the memory card and inserted it into a laptop. We watched in beautiful clarity as a fox, and then a goshawk, and then a kookaburra fed on the slowly deflating body of the kangaroo. Waters laughed and cursed, but it was clear that no amount of disappointment would dampen his belief. “It’s a fucking big country,” he said. “There’s a lot of needles in that haystack.”

Tasmanian Wolf DNA

In 2002, scientists reported they had replicated Tasmanian wolf DNA extracted from a small wrinkled pup, preserved in alcohol in 1866. The scientists worked uner Australian Museum director Mike Archer, the founder of a project to clone Tasmanian wolves. Researchers working with Don Colgan, head of the museum’s evolutionary biology department, extracted DNA from the Tasmanian wolf preserved in alcohol. Biologist Karen Firestone obtained additional Tasmanian wolf DNA from a tooth and a bone. Using a technique called polymerase chain reaction, they copied Tasmanian wolf DNA fragments. [Source: Luba Vangelova, Smithsonian magazine, June 2003]

In 2008 scientists reported they had brought a piece of Tasmanian wolf DNA back to life by inserting it into a mouse embryo. A special dye revealed that the extinct DNA turned on and formed skeleton marks of its own. DNA taken from the hair of two extinct Tasmanian wolves suggests that DNA taken from hair could be o resurrect extinct animals researchers reported in January 2009 in journal Genome Research. According to Reuters: The researchers used the method they used to study the DNA from extinct woolly mammoths’ hair. They got sequences both from the nucleus of the cell, and the mitochondria, where DNA is passed down with few changes from mother to offspring. [Source: Reuters, January 13, 2009; National Geographic, 2009]

In 2017, a Tasmanian wolf’s genome was successfully sequenced from the pup used in 2002. In 2023, scientists recovered and sequenced RNA from a 130-year-old Tasmanian wolf specimen preserved at room temperature in Sweden's Museum of Natural History. In October 2024, Colossal Biosciences said its reconstructed Tasmanian wolves genome is about 99.9 percent complete, with 45 gaps that they'll work to close through additional sequencing in the coming months. CBS News reported: The company also isolated long RNA molecules from a 110-year-old preserved head, which was skinned and kept in ethanol. "Tasmanian wolves samples used for our new reference genome are among the best preserved ancient specimens my team has worked with," said Beth Shapiro, Colossal's chief science officer and the director of the UCSC Paleogenomics Lab, where the samples were processed. "It's rare to have a sample that allows you to push the envelope in ancient DNA methods to such an extent." [Source Aliza Chasan, CBS News, October 21, 2024]

The preservation of a complete Tasmanian wolf head meant that scientists could study RNA samples from several important tissue areas, including the tongue, nasal cavity, brain and eye. It will allow researchers to determine what a Tasmanian wolves could taste and smell, along with what type of vision it had and how its brain worked, according to Andrew Park, a member of Colossal's Scientific Advisory Board and a researcher at the University of Melbourne's TIGRR Lab.

Bringing Back the Tasmanian Wolf

Researchers in Australia and the U.S. — through a partnership between scientists at the University of Melbourne and Texas-based company Colossal — are engaged in a multi-million dollar project to bring the Tasmanian wolf back from extinction using recreated using stem cells and gene-editing technology. The group aims to take stem cells from a living marsupial species with similar DNA to Tasmanian wolves and then use gene-editing technology to "bring back" the extinct species — or an extremely close approximation of it. [Source: BBC, August 17, 2022]

The Tasmanian Wolf Integrated Genomic Restoration Research (TIGRR) Lab, which is led by Andrew Pask, a professor of epigenetics at the University of Melbourne, is at teh center of the effort to bring Tasmanian tigers back from the dead. "We're getting closer every day to being able to place Tasmanian wolves back into the ecosystem — which of course is a major conservation benefit as well," Pask said. Pask told 60 Minutes in 2024 that researchers were working with the closest living relative of the Tasmanian wolf — a small marsupial called the fat-tailed dunnart — as a way to bring the animal back."But that little dunnart is a ferocious carnivore, even though it's very, very small," Pask said. "And it's a very good surrogate for us to be able to do all of this editing in." Scientists have been comparing the DNA of the dunnart and Tasmanian wolves, Pask told 60 Minutes. From there, it's a matter of going in and editing the DNA to turn a fat-tailed dunnart cell into a Tasmanian wolves cell. [Source Aliza Chasan, CBS News, October 21, 2024]

Colossal Biosciences said it had edited more than 300 unique genetic changes into a dunnart cell, making it "the most edited animal cell to date." "We are really pushing forward the frontier of de-extinction technologies," Pask said, "from innovative ways of finding the regions of the genome driving evolution to novel methods to determine gene function. We are in the best place ever to rebuild this species using the most thorough genome resources and the best informed experiments to determine function." "Because the Tasmanian wolf is a recent extinction event, we have good samples and DNA of sufficient quality to do this thoroughly," Pask told Live Science. "The Tasmanian wolf was also a human-driven extinction, not a natural one, and importantly, the ecosystem in which it lived still exists, giving a place to go back to." [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 12, 2023]

The idea of bringing back the Tasmanian wolf has been around for more than 20 years — In 1999, the Australian Museum started to pursue a project to clone the animal, and various attempts have been made at intervals ever since to extract or rebuild viable DNA from samples. Those in favor of reviving Tasmanian wolves say the animals could boost conservation efforts. "The Tasmanian wolf would certainly help rebalance the ecosystem in Tasmania," Pask said. "In addition, the key technologies and resources created in the Tasmanian wolf de-extinction project will be critical right now to help preserve and conserve our extant endangered and threatened marsupial species."

Objections to Bringing Back the Tasmanian Wolf

Many scientists oppose the whole idea of bringing back the Tasmanian wolf . "De-extinction is a fairytale science," Associate Professor Jeremy Austin from the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA told the Sydney Morning Herald, adding that the project is "more about media attention for the scientists and less about doing serious science". [Source: BBC, August 17, 2022]

De-extinction is extremely complex and costly, according to the National Museum Australia. Those against it, however, say that it distracts from preventing newer extinctions and that a revived Tasmanian wolf population could not sustain itself. "There is simply no prospect for recreating a sufficient sample of genetically diverse individual Tasmanian wolves that could survive and persist once released," Corey Bradshaw, a professor of global ecology at Flinders University, told The Conversation. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, May 12, 2023]

Colossal Biosciences is a biotech and genetic engineering startup co-founded by Harvard geneticist George Church. It is involved in plans to bring back woolly mammoths and made headlines when they claimed they brought back dire wolves. Thor actor Chris Hemsworth is a supporter of the effort to “de-extinct” Tasmanian wolves by using gene-editing technology. The ultimate goal is to reintroduce the marsupials to its once-native habitats in order to rewild the ecosystems that were damaged after losing the species. Critics point out that Colossal is a business looking to make money that has noble aims but also may be looking to create Jurassic-Park-like spectacle and entertainment. [Source: Tony Ho Tran, Daily Beast, August 17, 2022]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025