Home | Category: Animals / Marsupials

DASYURIDS AND DASYUROMORPHS

Dasyuromorphs (clockwise from upper left): 1) Tasmanian wolf; 2) Tasmanian devil; 3) Tiger quoll; 4) Numbat; 5) Yellow-footed-antiechinus; 6) Fat-tailed dunnart

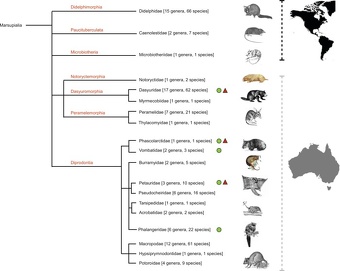

Dasyurids (Dasyuridae) are a family of marsupials native to Australia and New Guinea, including 71 extant species divided into 17 genera. Many are small and mouse-like or shrew-like so its no surprise they are often called marsupial mice or marsupial shrews, but the group also includes larger animals such cat-sized quolls and Tasmanian devils. Dasyurids are found in a wide range of habitats, including grassland, underground, forests, and mountains. Some species are arboreal (live mainly in trees); others are semiaquatic. The Dasyuridae are often called the 'marsupial carnivores', as most members of the family are carnivores, mostly insectivores. [Source: Wikipedia]

Dasyuromorphia (Dasyuromorphs), meaning "hairy tail", is the order comprising most Dasyurids. Dasyuromorphs are more or less the same as Dasyurids, plus numbats. They include quolls, dunnarts, the numbat, the Tasmanian devil, and the extinct thylacine. The order contains four families: one, the Myrmecobiidae, with just a single living species (the numbat), two with only extinct species (including the thylacine and Malleodectes), and one, the Dasyuridae, with 73 extant species. [Source: Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Almost a quarter of Dasyuridae have only been scientifically recognised since the late 1990s. Taxonomists divide Dasyurids into four subfamilies, the Dasyurinae (quolls, Tasmanian devil, kowari, mulgara, kaluta, dibblers, pseudantechinuses, and parantechinuses), Phascogalinae (phascogales and other antechinuses), Sminthopsinae (dunnarts and kultarr), and Planigalinae (planigales and ningauis). Evidence for the cohesiveness of the entire group, however, is strong. [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]|

Dasyurids are restricted to Australia, New Guinea, Tasmania, and some small nearby islands. They live in temperate and tropical land environments in deserts, dune areas, savannas, grasslands, forests, rainforests, scrub forests, mountains, and suburban and agricultural areas. Dasyurids coexist with other species in these environments by feeding on available resources that other types of animals don't eat so much. In the desert, dasyurids forage above ground on clay soils, sand dunes, rocks, and grasslands. In the temperate and tropical forests, dasyurids may be arboreal (live mainly in trees), as well as terrestrial, searching for prey in the trees. Terrestrial dasyurids search for food a few feet above the ground in shrubs and hollow trees. Larger dasyurids, such as eastern quolls and Tasmanian devils, avoid competitors by foraging primarily in the trees. |=|

RELATED ARTICLES:

NUMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLL SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVIL CONSERVATION: HUMANS AND THE DEADLY DISEASE RAVAGING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLF EXTINCTION, SIGHTINGS, SEARCHES, BRINGING IT BACK ioa.factsanddetails.com

SMALL MARSUPIAL CARNIVORE SPECIES: MULGARA, DIBBLERS, KULTARRS, NINGAUI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DUNNARTS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLANIGALES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANTECHINUSES: SPECIES, FALSE ONES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUICIDAL MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Dasyurid History

In Australia, the oldest known members of the order Dasyuromorphia originated from south Queensland at least 55 million years ago. The primary radiation of marsupials occurred in Antarctica, and the order Dasyuromorphia first arose around 65 million years ago. Dispersal to Australia occurred by 63 million years ago. The first labeled dasyuromorph, Djarthia murgonensis, has been dated to the early Eocene period (56 million to 47.8 million years ago, around 55 million years ago. |=|

Little is known about their evolution between the late Paleocene Period (55 million years ago) and the late Oligocene Period (about 24 million years ago). Fossil records are abundant from the Early Miocene (23 million to 16 million years ago), as the warm and wet greenhouse period resulted in high levels of diversity in rainforest communities. As rainfall decreased around 15 million years ago and Australia became cooler and drier, there was a steady and rapid increase in diversity of dasyuromorphs. Thereafter, with the arrival of humans and increased aridity, family-level diversity declined to the present level. [Source: Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The early radiation of Dasyuromorphia was comprised mostly of “primitive” thylacinids,ranging in size from that of a small dog to approximately 65 pounds. Thylacinids were dominant carnivores (animals that mainly eat meat or animal parts) throughout Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania until the Miocene Period (23 million to 5.3 million years ago), when the population began to decline, likely because of competition from other large carnivorous marsupials. Only one species survived to modernity: the Tasmanian wolf.

Dasyurids originated, flourished and replaced thylacinids as the reining carnivorous marsupials in the middle of the Miocene Period (23 million to 5.3 million years ago). Fossil evidence for early dasyurids dates back to the Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). At this time, all modern dasyuromorph taxa were represented, including numbats.

During the Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), land bridges connected the Australian mainland to New Guinea and Tasmania, allowing the exchange of faunas between these land masses. Modern distributions and genetic relationships of particular species serve as evidence of the interchange of fauna during this era. Because the Pleistocene Period was characterized by cooler temperatures, savanna and woodland species primarily migrated across the land bridges. Disappearance of the Tasmanian wolf from the mainland of Australia and New Guinea is thought to be due to the introduction of domestic dogs by native Aborigines 10,000 years ago.

Dasyurid Characteristics

Some Dasyurid species: 2) Crest-tailed Mulgara (Dasycercus cristicauda); 3) Kowari (Dasyuroides byrnei); 4) Kaluta (Dasykaluta rosamondae); 5) Dibbler (Parantechinus apicalis); 6) Woolley's Three-striped Dasyure (Myoictis leucura); 7) Miller's Three-striped Dasyure (Myoictis melas); 8) Wallace's Three-striped Dasyure (Myoictis wallacii); 9) Tate's Three-striped Dasyure (Myoictis wavicus); 10) Sandstone Pseudantechinus (Pseudantechinus bilarni); 11) Fat-tailed Pseudantechinus (Pseudantechinus macdonnellensis); 12) Carpentarian Pseudantechinus (Pseudantechinus mimulus); 13) Ningbing Pseudantechinus (Pseudantechinus ningbing); 14) Rory’s Pseudantechinus (Pseudantechinus roryi); 15) Woolley's Pseudantechinus (Pseudantechinus woolleyae); 16) Speckled Dasyure (Neophascogale lorentzii); 17) Red-bellied Phascogale (Phascolosorex doriae); 18) Narrow-striped Dasyure (Phascolosorex dorsalis))

Dasyurids range in size from roughly from five or six grams to eight kilograms. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. male larger Phil Myers wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Despite their variation in size, most are similar in shape, with a moderately long body, long pointed head, long and usually fairly well-furred tail, and short to medium-length legs. The tail is not prehensile. [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The feet are not fused together (that is, the second and third toes are not fused), and the animals walk with the entire surface of their feet on the ground ( plantigrade (walking on the soles of the feet, like a human or a bear)). Arboreal (live mainly in trees), species have a small but mobile big toe on the hind foot, but this toe tends to be reduced or absent in terrestrial species. The hind foot of terrestrial species also tends to be longer than that of arboreal (live mainly in trees), species. Many dasyurids lack a pouch; in these species, the teats are arranged on a circular patch of skin on the abdomen. Some that lack a pouch have folds along the sides of the abdomen that give young some protection. The stomach of dasyurids is a simple sac.

The skull of dasyurids is didelphid-like in appearance, but it include four upper and three lower incisors on each side of the jaw rather than 5/4 as in didelphids. The canines are well developed and have a sharp edge; the premolars (2 or three upper and lower on each side) are blade-like; and the molars (4 upper and lower) are tuberculosectorial, often with sharp cusps for shearing. The palatal vacuities that characterize most marsupials are reduced or absent in some species. |=|

Dasyuomorphs Diet, Food and Predators

Dasyuomorphs are primarily insectivores (eat insects) but also recognized carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and can be scavengers and omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals), They may store and cache food.

Dasyuomorphs are generalized predators that eat a wide range of invertebrate and vertebrate prey. Numbats are insectivorous, and one individual can consume 10,000 to 20,000 termites each day. Other families within Dasyuridia are carnivorous. They catch and eat both terrestrial and arboreal (, insects, including moths, beetles, and mosquitoes. Large species are also known to eat juvenile mice. [Source: Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Before placental carnivores such as cats and foxes were introduced to Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania, dasyurids were the most prominent large predators. They still remain key predators, consuming a wide range of vertebrate and invertebrate prey. According to Animal Diversity Web: Vision and olfaction play key roles in hunting. Most dasyurid species possess vibrissae that help orient their attack toward prey; however, visual and tactile methods are also employed. Carnivorous marsupials bite or pin their prey with their forepaws. Bites are directed toward the anterior part of the body (head or neck) in order to assure capture. They are also known to shake and toss prey if they show resistance.

Dasyurid are vulnerable to reptilian, avian, and mammalian predators. They do not have any physical adaptations to deter predators and thus tend to minimize predation by foraging at night and under protective covering. Small dasyurids are particularly vulnerable to introduced European red foxes. Domestic dogs, dingoes, and domestic cats also prey upon dasyurids.

Dasyurids Behavior

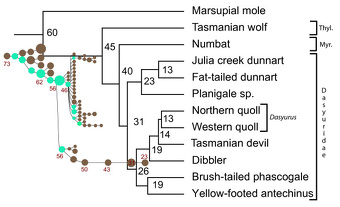

Phylogeny of Dasyuromorphia based on complete mt genomes; Phylogenomic relationships among dasyuromorphian subfamilies, including the position of the Tasmanian devil, based on complete mitochondrial genomes; The numbers in black at the nodes of the tree are divergence times calculated from a 44-taxon matrix using a combined set of 13 fossil calibration points; The circles plotted beside the tree are the results of a COSEG analysis of the 66 subfamilies of WSINE1; Brown circles indicate different subfamilies and blue circles the subfamilies that gave rise to new subfamilies; The red numbers beside the circles indicate the estimated evolutionary age for selected subfamilies; Thyl: Thylacinidae; Myr: Myrmecobiidae

Dasyurids are generally solitary, nocturnal (active at night) and crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and can be arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (good at climbing), terricolous (live on the ground), territorial (defend an area within the home range). and employ aestivation (prolonged torpor or dormancy such as hibernation) and have daily torpor (a period of reduced activity, sometimes accompanied by a reduction in the metabolic rate, especially among animals with high metabolic rates). [Source: Phil Myers, Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Dasyurids tend to be nocturnal or crepuscular but occasionally forage or bask during the daytime. According to Animal Diversity Web: They exhibit long-range movements and often shift home ranges. Most species of dasyurids are solitary and typically only form small groups while mating or rearing young. They build burrows and nests, which they add to during pregnancy and as young develop. Some species groom themselves, especially after feeding, which involves washing the face, snout, nape of the neck, throat and chin with licked forepaws. Dasyurids (Dasyuridae) use their forepaws not only to catch and eat prey but also in tactile social interactions where they grasp and pull one another. |=|

To cope with unpredictably fluctuating food supplies, dasyurids utilize a variety of strategies to conserve body heat and reduce energy expenditures. One strategy involves lowering metabolic rates when resources are particularly scarce. Because dasyurids cannot sweat, they lick and pant to keep cool. Because of the diverse habitats in which they live, strategies to conserve body heat and reduce energy loss vary greatly. Strategies include having a spherical body shape to maximize heat conservation, increasing fur thickness in the winter, living in protected hollows during the day to avoid the heat, lining nests with leaves, and huddling in groups.

Dasyurid Senses and Communication

Dasyurids sense and communicate mainly with touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also employ pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them [Source: Phil Myers, Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

According to a Animal Diversity Web: Due to their nocturnal habits, dasyurids have reduced their dependence on sight for communication and perception and have adapted olfactory and auditory mechanisms to compensate. Dasyurids utilize chemical signals such as scent markers as a primary mode of communication. Commonly used chemical signals include urine dribble, cloacal drag, chin rub, and sternal rub. These are used to mark territory or as a status signal during breeding. Other social behaviors, such as mouth sniffing, naso-nasal sniffing, touching, and cloacal sniffing have been observed. Cloacal sniffing is especially important in male-female interactions. |=|

Auditory communication is also common in dasyurids. Vocalizations are mostly associated with defensive situations, such as nest defense, food defense, and threats but are also used in parent-offspring interactions as well as courtship and mating. Dasyurids emit a chatter, tail rattle, foot tap, huff, or bark as an alarm mechanism when they feel threatened or in danger. Defensive vocalizations include hisses, huffs, grunts, growls and screams. When separated from their mother, young dasyurids produce vocalizations that trigger mother retrieval behavior. |=|

Dasyurids also possess vibrissae that orient their attacks during predation. Males use tactile communication during mounting and copulation by grasping the neck and abdomen of the female.

Dasyurid Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Dasyurids tend to be polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners and engage in seasonal breeding. They employ sperm-storing (producing young from sperm that has been stored, allowing it be used for fertilization at some time after mating) and use delayed fertilization in which there is a period of time between copulation and actual use of sperm to fertilize eggs; due to sperm storage and/or delayed ovulation. Gestation time varies greatly with body size, as does time spent in the mother's pouch. After the brief mating season, male dasyurids leave females with all parental responsibilities. In semelparous species, such as antechinuses, males die before their offspring are born. [Source: Phil Myers, Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Both male and female dasyurids practice promiscuous mating during a relatively short but intense breeding season. Larger males are more successful at attracting females and fighting off competing males. During courtship, males display antagonistic behavior in which they chase the female. During copulation, the male grips the female’s neck with his teeth and clasps her body with his forepaws to facilitate mounting. This continues throughout copulation, which lasts several hours. While copulating, males in the genus Antechinus can turn their bodies 180 degrees to ward off other males. After mating, males may guard a female for up to 12 hours to prevent other males from mating with her. Male Tasmanian devils are particularly aggressive during mate guarding and do not allow the female to leave her den for food or water for days. Occasionally females are able to escape these aggressive males but usually not without injury. |=|

Females release pheromones to signal their receptivity to mate. They solicit males they find attractive and ward off other males. Females have long periods of behavioral estrus which allow them to mate with several males unless particularly aggressive males prohibit their ability to do so. Thus, multiple paternity as a result of sperm competition is often observed. For example, it is not uncommon for a litter of four Tasmanian devils to have four different fathers. Dasyurids exhibit a unique form of sperm competition, and, other than bats, they are the only mammals in which females can store competing sperm within their reproductive tracts prior to ovulation.

Dasyurids are either semelparous (reproduce only once in a lifetime, after which they typically die) or iteroparous (reproduce multiple times during their lifetime). Among semelparous ones, males often die before their offspring are born Semelparity is very rare in mammals, having arisen only in dasyurids and didelphids. Semelparous dasyurids, such as antechinuses, generally live in environments with predictable seasonal patterns of food abundance. It is thus advantageous to align reproductive patterns with seasonal variation in resource abundance. The mating season occurs in the winter when resources are scarce, and consequently young are born when resources are most abundant. Because seasonal patterns are so predictable, it not risky to dedicate all of their reproductive efforts into one brief mating season. |=|

Males devote most of their energy to one big reproductive effort, and as a result have high concentrations of stress hormones in their blood. This inhibits inflammatory and immune responses and eventually kills the exhausted males. Females may survive for a second breeding season but almost never survive for a third. Semelparous dasyurids are characterized by prolonged copulation, large testes size, male Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: , mate guarding, long behavioral estrus of females, sperm storage in female reproductive tracts, high population densities, and sperm competition. |=|

Iteroparous dasyurids, on the other hand, reside in less restricted, less predictable environments. Therefore, it is risky to invest all of their energy into one reproductive effort when resource levels are so unpredictable. During the breeding season, Northern quolls exhibit normal levels of stress hormones and have larger body sizes and tail fat stores that help them survive to the next breeding season. Iteroparous dasyurids do not display any of the identifying characteristics of semelparous dasyurids. Additional reasons for semelparity in some species and iteroparity in others are not well understood.

Among dasyurids parental care is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. During lactation, many dasyurid mothers are biased towards their male offspring and provide them with more nutrient-rich milk. Because larger males are more successful in attracting mates and reproducing, it is advantageous for mothers produce larger males that have a better chances of passing on her genes. After leaving the pouch permanently, young are carried into well-hidden dens. Dens are lined with vegetation for protection and warmth and are located in underground burrows, caves or hollow logs. As young near weaning, mothers take more frequent trips outside of the den. When mothers begin to sleep away from their young, male offspring disperse from the den. Males move away from their mother's home range while females remain in their mother’s home range for life. |=|

Dasyurids Humans and Conservation

According to Animal Diversity Web :Dasyurids, like other marsupials, are held in great regard by the native Australian Aborigines. Cultural practices such as dreaming stories, myths, rituals and totems were devoted to dasyurids, especially the larger species. Australian Aborigines have hunted many species of dasyurids as a source of food for thousands of years. On their arrival, European settlers also hunted dasyurids for food. . [Source: Phil Myers, Nicole Armbruster Chad Nihranz and Elizabeth Colvin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Dasyurids have not fared since the arrival of Europeans to Australia more than a century ago. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list, six species are listed as Endangered, one species, Kangaroo Island dunnarts (Sminthopsis aitkeni), as critically Endangered and one species, Tasmanian wolves, as extinct.

Currently, the most prominent threat to dasyurids is the rapidly expanding human population. Clearing land for agriculture, draining and salination of wetlands, and grazing by livestock both destroys and fragments habitat. Introduced placental carnivores like red foxes have decimated populations by preying on smaller dasyurids and competing with larger ones. Additionally, climate change has resulted in drought and uncontrollable fire regimes that alter their habitat. Because they rely on a large number of omnivores and herbivores prey to survive, dasyurids are vulnerable to small changes in their habitat. |=|

Today, efforts are being made to remove rabbit populations from known dasyurid habitats. Rabbits not only damage the habitat of dasyurids but also attract predators like dingoes and red foxes. Today, nearly all dasyurids are protected from hunting and over-harvesting under the laws of the states and territories of Australia.

Biologists often catch small animals in a pit traps, a plastic pipe that is buried along a fence. When animals reached the fence they will run along until the they fall in the pipe.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025