Home | Category: Marsupials

ANTECHINUSES

Antechinus Species: 29) Black-tailed Antechinus (Antechinus arktos); 30) Fawn Antechinus (Antechinus bellus); 31) Yellow-footed Antechinus (Antechinus flavipes), 32) Atherton Antechinus (Antechinus godmani); 33) Cinnamon Antechinus (Antechinus leo); 34) Swamp Antechinus (Antechinus minimus); 35) Buff-footed Antechinus (Antechinus mysticus); 36) Brown Antechinus (Antechinus stuartil); 37) Subtropical Antechinus (Antechinus subtropicus); 38) Dusky Antechinus (Antechinus swainsonii)

Antechinus is a genus of small dasyurid marsupial endemic to Australia. Members of this genus — antechinuses — mainly eat insects and resemble mice with the bristly fur of shrews. They are sometimes called 'broad-footed marsupial mice', 'pouched mice', or 'Antechinus shrews'. However, the majority of those common names are considered either regional or archaic and are sometimes used to described species in other genuses. The modern common name for these animals is antechinus. The word "Antechinus" comes from Greek roots, meaning "not a hedgehog". When they were first discovered they were thought to be related to hedgehogs. [Source: Wikipedia]

There are 15 species of antechinus; Generally, the clades are made up of species found in the same general region:

Clade 1: dusky antechinus

black-tailed antechinus (Antechinus arktos)

mainland dusky antechinus (Antechinus mimetes)

swamp antechinus (Antechinus minimus)

Tasmanian dusky antechinus (Antechinus swainsonii)

Tasman Peninsula dusky antechinus (Antechinus vandycki)

Clade 2

Atherton antechinus (Antechinus godmani)

Clade 3: brown antechinus

agile antechinus (Antechinus agilis)

brown antechinus (Antechinus stuartii)

subtropical antechinus (Antechinus subtropicus)

Clade 4

silver-headed antechinus (Antechinus argentus)

rusty antechinus (Antechinus adustus)

fawn antechinus (Antechinus bellus)

yellow-footed antechinus (Antechinus flavipes)

cinnamon antechinus (Antechinus leo)

buff-footed antechinus (Antechinus mysticus)

Antechinus are generally greyish or brownish in color, Their short fur is dense and generally soft and their rat-like tails range from slightly shorter to slightly longer than body length. Their heads are conical in shape and ears are small to medium in size. Some species have a relatively long, narrow snout that gives them a shrew-like appearance. Adults of the different species vary in size 12 to –31 centimeters (4.7 to 12.2 inches) in length and weigh 16 to 170 grams (0.56 to 6 ounces). Agile antechinuses are the smallest known species, and dusky antechinuses in Tasmania are the largest.

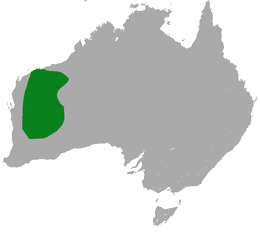

Most species nest communally in tree-hollows and die young. They primarily inhabit forests, woodlands and rainforest. Some species can be found in heaths and grasslands. The majority of Antechinus species are located on the eastern coast of Australia along the Great Dividing Range. There is a population of yellow-footed antechinuses in south west Western Australia. Fawn antechinuses live in northern Australia around the Gulf of Carpentaria.

RELATED ARTICLES:

DASYURIDS AND DASYUROMORPHS (MARSUPIAL CARNIVORES) ioa.factsanddetails.com

SMALL MARSUPIAL CARNIVORE SPECIES: MULGARA, DIBBLERS, KULTARRS, NINGAUI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DUNNARTS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLANIGALES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

NUMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLL SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Suicidal Sex Lives of Antechinuses

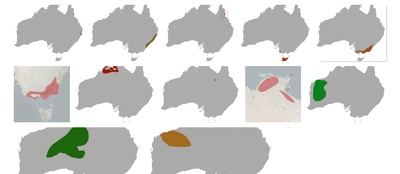

Range of some Antechinus and False Antechinus species: Top row left to right: 1) Subtropical Antechinus (Antechinus subtropicus); 2) Brown Antechinus (Antechinus stuartii); 3) Atherton Antechinus (Antechinus godmani); 4) Swamp Antechinus (Antechinus minimus)’ 5) Agile Antechinus (Antechinus agilis)

Middle row left to right: 1) Agile Antechnius IUCN Range; 2) Ningbing False Antechinus; 3) Alexandria False Antechinus; 4) Sandstone False Antechinus IUCN Range; 5) Woolley's False Antechinus (Pseudantechinus woolleyae)

Bottom row left to right: 1) Fat-tailed False Antechinus; 2) Rory Cooper's False Antechinus (Pseudantechinus roryi)

Male antechinuses, unlike female ones, are semelparous, which means they can only breed once during their lifetime. Typically all males die shortly after mating in their 11th or 12th month of life. This phenomenon occurs at the same time each year in any given population. How the die off occurs is not totally clear. Possibilities include elevated corticosteroids — steroid hormones — and sleep deprivation. Increased physiological stress results from aggression and competition between males for females, and heightened activity during breeding season. Increased stress levels apparently cause suppression of the immune system after which the animals die from parasites of the blood and intestine, and from liver infections. In the wild, many females die after rearing their first litter, although some do survive a second year. [Source: Ross Secord, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Katherine J. Wu and Rachael Lallensack wrote in Smithsonianmag.com: For a two- or three-week stretch in early spring, Australian forests reverberate with the sexual shenanigans of the male antechinus. These tiny, tireless marsupials can engage in a single intimate encounter for 14 hours straight. Desperate, virile and indefatigable, each of these bitty boys will mate with as many females as possible, plugging away until the fur sloughs off his skin, his immune system fails and blood pools around his organs. In a grand culmination of this fornication feat, the male antechinus physically disintegrates: He quite literally boinks himself to death, usually just shy of his first birthday. [Source: Katherine J. Wu , Rachael Lallensack, Smithsonianmag.com, February 14, 2020]

This So-called suicidal reproduction might sound absurd, but vigorous, organ-shredding sex is the antechinus males’ way of outcompeting each other in the reproductive race to father the most young. The more sperm a male churns out, the more successful he’ll be. A sexual sprint to the death is the antechinus’ one shot at passing on his genes, and he puts every second of it to good use.

Sleeplessness During the Intense Antechinus Breeding Season

During the mating season males in particular don’t sleep much, arguably because time spent sleeping could deny them the opportunity to pass on their genes. In a study published in January 2024, in the journal Current Biology, scientists described how male antechinuses endured extreme sleep deprivation to mate, with one monitored male halving his sleep time during the breeding season. “Animals need to reproduce to pass on their genes, but they also need to sleep to survive,” Erika Zaid, lead author and animal behavior researcher at La Trobe University in Melbourne, told CNN. “Animals that are long-lived like humans and elephants don’t have this pressure to reproduce in a short period of time. They have the luxury of being able to sleep as long (as) they want (and) need each day,” she said. [Source: Hafsa Khalil, CNN, January 26, 2024]

Non-breeding dusky antechinus spend an average of 15.3 hours of the day asleep, according to the researchers. But breeding ones sleep up to 80 percent less. “Sleep restriction in breeding male antechinus is likely to be an adaptive behavioral response driven by strong sexual selection,” the paper said. This drives them to compete with other males to reproduce with as many females as possible, before dying shortly after their first — and last — mating season.

Hafsa Khalil of CNN wrote: To study the semelparous marsupials, researchers examined two antechinus species: dusky antechinus and wild agile antechinus both captive and wild. Researchers found that males from both species were not only more active during mating season, but also slept less during the same period. Data showed that males were sleeping three hours less per night, every night, for three weeks — approximately the length of the mating period. Males, which only live for 11 months, reproduce once in their lifetime before dying while females can reproduce more than once, Zaid said.

Sleep is “an essential and seemingly universal behavior in the animal kingdom,” said John Lesku, associate professor of zoology at La Trobe University and a sleep scientist, who was involved in the study. “Sleeping three hours less per night impacts waking performance in humans, (while) antechinus did this for three weeks. Therefore, antechinus may be resilient to sleep loss and have an unknown mechanism to thrive on less sleep during this time, or they may accept the physiological costs of staying awake to secure paternity before they die,” Lesku told CNN. The paper suggests that sleep reductions were due to the reproductive pressures on the males during their only breeding season, with increased sexual activity positively related to increases in testosterone, the male sex hormone, during the same length of time.

Using accelerometers — instruments used to measure the acceleration of a moving body — the researchers tracked the movement of 15 dusky antechinus (10 male) before and during mating season.Researchers took blood samples to measure any changes in hormones and took electrophysiological recordings from four males to measure how much they were sleeping.Blood samples were also taken from 38 wild agile antechinus (20 male) to see if oxalic acid, a biomarker for sleep loss, similarly decreased during the mating period.

While the decrease in oxalic acid suggests the agile antechinus were sleep deprived during mating season, the results show that the difference between males and females was not significantly different, which Zaid points out may suggest that females in the wild are similarly sleep deprived due to male harassment during the mating period. “Our study is the first to compare male and female activity levels before, during, and after the breeding season, and to reliably relate restfulness with sleep using accelerometry, electrophysiology, and metabolomics,” researchers said in the paper. Volker Sommer, a professor of evolutionary anthropology at University College London, told CNN: “It rather seems that this is some pre-breeding stale-mate in not letting one’s guard down: males are forced to stay awake because their competitors also do.”

Dusky Antechinuses

Dusky antechinuses (Antechinus swainsonii) are also known as Swainson's antechinuses and dusky marsupial mice. The largest antechinus, they are found in south-eastern Australia, from southern Queensland to eastern South Australia, throughout Victoria and New South Wales, and in Tasmania. Dusky antechinuses are most commonly found in the moist sclerophyll (hard leaf) forests and rainforests of the Australian mainland and Tasmania. They have also been found in fields overgrown with high grasses but prefer habitat with a dense understory, where they do most of their activities. Dusky antechinuses are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Habit losse and predation by domestic cats are the main threats to these and many other antechinuses. [Source: Jeremy Bates, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Dusky antechinuses range in color from dark gray to black and range in weight from around 41 to 65 grams (1.4 to 2.3 ounces). The average head and body length is 12.8 centimeters (t inches) and the average tail length is 11.6 centimeters (4.6 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females.The average weight of males 65 grams 2.3 ounces). The average weight of females 41 grams (1.44 ounces). Males reach 130 grams (4.6 ounces) and females reach 70 grams (2.5 ounces). It is believed weight fluctuates due to availability of food. The average basal metabolic rate of these animals is 0.351 watts

Dusky antechinuses feed mostly invertebrates that live in the soil or on the forest floor such as worms and insects but have also been observed eating lizards, small birds, fruit and vegetation. They spend most of their active period feeding. Some have been estimated to eat about 60 percent of their body weight during the winter months. In captivity individuals are fed earthworms, mealworms, grasshoppers, beetle larvae, cockroaches, and small frozen mice.

Dusky antechinuses are terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary. Captive dusky antechinuses are documented being active day and night with periods of extended periods of rest around 12 p.m. and six a.m. Fully developed adults are solitary with social activity limited to mating and between mother and young. Members of the species seem to have a definite home range, but are not territorial. Dusky antechinuses construct nests from eucalypt leaves that are balled up in hollow tree trunks or in the dense understory of the forest floor .

Dusky Antechinus Mating, Offspring and Death

Female dusky antechinuses usually die after rearing their first litter and males die shortly after copulation. Males captured after breeding season still die within the same time period as wild males from their population, but males captured before the breeding season have lived up to two years and eight months. Females can live over two years, producing a second litter, but as stated above most die after rearing one litter. There is a low mortality rate among young as considerable time and effort is invested maternally in rearing litters.

Jeremy Bates wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Competition for mates is extremely high among males. During mating, males have been observed to grab the scruff of the females neck with their teeth, while the females respond by kicking, rolling, and a display of open-mouthed hissing. During the breeding season males do not eat, but their body is sustained through gluconeogenic mobilization of body protein. This results in deterioration of the male's immune system and death usually within three weeks of copulation. These victims of male "die-off" have been found to have balding patches located on their fur. [Source:Jeremy Bates, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Females breed once, sometime between May and September, and there is considerable evidence that the timing of breeding is correlated with environmental conditions. Populations in coastal regions and at lower altitudes have earlier breeding seasons than inland or higher-elevation populations, and populations on the mainland breed earlier than those on Tasmania. Availability of food, temperature, altitude and climate may all play a role in the timing of a population's breeding season.

Gestation lasts 29 to 36 days. In captivity females show visible signs of enlarged nipples 19 days after copulation; an enlarged, but concealed, pouch at 21 days; and by 23 days, a pouch that is divided into two halves by a ridge. The pouch only becomes visible a few days before birth. A birthing female places herself on all fours with her hindquarters up slightly as the young emerge. Dusky antechinuses produce supernumery offspring (more offspring than available teats), and some offspring do not reach an available teat, resulting in their death.

Young average 4.5 millimeters in length at birth with well developed claws on their forelimbs, and a large circular mouth. A sexually mature female has eight teats and litter size ranges from 6-8 young. The young are bright pink at birth, but begin to develop fur at eight weeks with their eyes opening shortly after. The young are left alone in the nest at 10 weeks and begin to eat solid food at 12 weeks. By the 14th week the young are completely weaned and travel outside of the nest attached to their mothers back. Dusky antechinuses develop slowly and are fully mature around eight months, near the beginning of the next breeding season. Males and females on average age reach sexual or reproductive maturity at eight months.

Brown Antechinuses

Brown antechinuses (Antechinus stuartii) are also known as Stuart's antechinuses and Macleay's marsupial mice. Males die after their first breeding season and species are the world's smallest semelparous mammals. Resembling mice, brown antechinuses have a long pointed head, relatively large ears, elongated hind feet and a pink nose. They are mostly light brown on their back, sides and the upper surfaces of their feet, and a lighter brown below and on its tail. Their head and body length ranges from 9.3 to 13 centimeters (3.7 to 5.1 inches), with a 9.2-to-20 centimeter (3.6-to-4.7 inch) tail and weighs 16 to 71 grams. Their average basal metabolic rate 0.189 watts. Unlike other Antechinus species they don’t have no pale-colored eye rings. Agile antechinuses look similar; the main way to tell them apart is by where they live. size. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males ranges in weight from 28 to 71 grams (1.0 to 2.5 ounces) and female ranges in weight from 17 to 36 grams (0.6–1.3 ounces). [Source: Wikipedia]

Brown antechinuses are found in eastern and southeastern Australia, in Victoria, New South Wales, and Queensland. They prefer wet sclerophyll (hard leaf) forests with dense ground cover with lots fallen trees in which they build nests. They usually stay on the ground, but may take to trees in drier areas, or where they live dusky antechinuses, which lives on the ground. Population densities range from less than one to eighteen per hectare. Outside the breeding season males and females have their own foraging ranges. The availability of habitat may be influenced by foresters that "ring" trees leaving the trunk and major branches to rot, which provides nesting sites [Source: Ross Secord, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Brown antechinuses are terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary During warm parts of the year individuals live in solitary nests and occupy their own home ranges. When temperatures drop, individuals of both sexes cluster together in nests with up to 18 animals to stay warm. Nests are fluid; individuals may change nests. A total of 28 females and 24 males were observed in one nest over one winter. Females typically nest alone to rear young and may split their offspring between nests in different trees. During the winter brown antechinuses may slip into a torpor for a few hours to lower their metabolic requirements.

Brown antechinuses primarily feed on invertebrates, particularly beetles, spiders, and cockroaches. They occasionally eat small vertebrates, such as mice as well as plant material and flower pollen. Brown antechinuses have a high metabolism and thuse have to ferocious predators just to keep up. During winter will consume as much as 60 percent of their weight in arthropods each day. They typically hunts at night but may be active during the day, especially during times when food is scarce, such as winter months.

Brown antechinuses are not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Habit losse and predation by domestic cats are the main threats to these and many other antechinuses.

Brown Antechinus Mating, Offspring and Death

On average male and female brown antechinus reach sexual or reproductive maturity at nine months. Males mate soon after this and die. Females may live to up to three years but often they too die after one breeding season. Brown antechinuses have a single breeding season of about three months, and produce one litter per year. Males leave their foraging ranges when the breeding season begins and group together in all-male nests during most of the night and become vocal, emitting staccato chirps, and becoming highly aggressive. Females remain solitary, but make excursions to the male aggregations. The average gestation period is 30 days. On average seven offspring are born.

Jacquie van Santen of ABC wrote: A female brown antechinus usually only breed once in her life, so she has added pressure to make sure her young have the best chance of surviving. In November 2006, researchers reported in Nature how a female stores the sperm of many suitors for up to two weeks in her ova ducts. Sperm from the 'strongest' males then go on to fertilise her prized eggs. And the result may be up to eight healthy offspring sired from four strong males. [Source: Jacquie van Santen, ABC, November 2, 2006]

To work this out and figure out what it might mean, Dr Diana Fisher and colleagues from the Australian National University conducted two separate mating experiments.In the first, they took female marsupials from the wild and when they were in season allowed them to mate either with a single male, or with three different males, every two days. A year later they replicated the experiment, but kept lactating females in captivity until just before weaning. This allowed the researchers to determine whether the previous benefit of polyandry depended on stressful conditions in their natural habitat, or could be replicated in the laboratory.

The researchers found the females in both populations weren't particularly fussy and, given the chance, mated happily with multiple partners. The only males they avoided in the wild were those that were obviously picked on by other males; those perceived as 'weak'. "By experimentally assigning mates to females, we were able to show that polyandry [females mating with more than one male during the mating season] greatly increases offspring survival," Fisher says."DNA profiling shows that males that gain high paternity under sperm competition sire offspring that are more viable." The researchers conclude that the practice of polyandry leads to 'better quality' offspring, an important factor in light of the fact that the marsupial will usually breed only once in her lifetime.

Females lack a pouch, instead they have exposed nipples. The number of nipples varies by habitat. Females that live in the wetter areas have six nipples while those in higher and drier areas have with 10 nipples. Births usually occur within a period of about two weeks for any given population. Newborns are four to five millimeters in length at birth and weigh an average of 0.016 grams. With the absence of a pouch, young cling to the mother's underbelly and may be dragged across the ground while she searches for food for about a five week period. Mothers may deny milk to male offspring, preferring to wean females. Mothers in captivity commonly eat their young. Young stay with the mother for about 90 days and reach sexual maturity in nine to 10 months. The young leave the mother with the onset of winter. [Source: Ross Secord, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

False Antechinuses

False antechinuses belong to the genus Pseudantechinus and are members of the order Dasyuromorphia. They are called false antechinuses, even though this genus includes the sandstone dibbler, which was previously assigned to a different genus. A distinguishing feature of most species within this genus is a bright orange, chestnut patch right behind each of their large ears, which are 1.3 to 1.9 centimeters (0.5 to 0.75 inches) in length. They also have distinctive broad hind feet that are 1.2 to 1.5 centimeters (0.5 to 0.6 inches) long.

False antechinuses are marsupials in the genus Pseudantechinus. "Antechinus" belong to a separate but related genus, Antechinus. False antechinuses were initially mistaken for antechinuses due to their similar appearance, hence the name "false". The key difference lies in their evolutionary history and, upon closer inspection, certain physical characteristics like tooth arrangement, number of teats and tail appearance. Both False antechinuses and antechinuses are small, carnivorous marsupials found in Australia and have mouse-like appearances. Antechinuses are known for their unique breeding behavior where males often die after mating. The similar appearance of false antechinuses and antechinuses is an example of convergent evolution — when unrelated species evolve similar traits due to similar environmental pressures or ecological niches. [Source: Google AI]

There are six false antechinus species:

Sandstone dibbler (Pseudantechinus bilarni)

Fat-tailed false antechinus (Pseudantechinus macdonnellensis)

Alexandria false antechinus (Pseudantechinus mimulus)

Ningbing false antechinus (Pseudantechinus ningbing)

Rory Cooper's false antechinus (Pseudantechinus roryi)

Woolley's false antechinus (Pseudantechinus woolleyae)

[Source: Wikipedia]

False antechinuses are similar-looking species. Woolley's false antechinuses are usually larger and have a third lower premolar with a dental formula of 4124/3134. Ningbing false antechinuses are smaller with proportionally longer tails. Females of this species have only four teats; other species have more. Alexandria false antechinuses have normal upper third premolars (compared to those greatly reduced in Fat-tailed antechinuses). Sandstone dibblers have a much proportionally longer and skinnier tail. Fat-tailed dunnarts (Sminthopsis crassicaudata) are usually smaller and do not possess the same chestnut patches behind the ears as false antechinuses. [Source: Christopher Wozniak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

False antechinuses generally require burrows for torpor to minimize energy waste, water loss, and exposure to potential predators. They also require basking sites within their habitat. These needs make antechinuses habitat specialists, resulting in scattered colonies across their geographic range. In Western Australia, fat-tailed false antechinuses occupy the same dry and rocky areas as Rory Cooper's false antechinuses hosting them. But Fat-tailed false antechinuses also inhabit savannahs, shrub steppes, and hummock grasslands including spinifex plains and basins. More rarely, they are also found in low-lying open woodlands.

In the past some Aboriginal people hunted antechinuses for food, and possibly some tribes may still do so today either by catching them off guard at the entrance of a termite mound or taking advantage of their habit of basking in the sun. Threats include habitat degradation and introduced species, particularly feral cats and foxes. Black-headed monitors (Varanus tristis) have been observed attempting to prey on fat-tailed false antechinuses. Other presumed natural predators include dingoes, other varanid lizards such as perenties and spiny-tailed monitors, snakes such as desert death adders, mulga snakes and eastern brown snakes, birds of prey such as whistling kites, brown goshawks and brown falcons. Western populations and Rory Cooper's false false antechinuses, have a red-brownish fur that resembles their red soils of the area where they live.

Fat-Tailed False Antechinuses

Fat-tailed false antechinuses (Pseudantechinus macdonnellensis) are also called fat-tailed pseudantechinuses and red-eared antechinuses. They are members of the order Dasyuromorphia. And an inhabitant of western and central Australia. Their species name, macdonnellensis, refers to the MacDonnell Ranges near Alice Springs, where they were first discovered. In the wild, one fat-tailed false antechinus in Alice Springs lived for five years and eleven months. In captivity, the longest recorded lifespan is seven years. [Source: Christopher Wozniak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Fat-tailed false antechinuses are found in the uplands of central Australia. Their range includes much of the central and northern Western Australia, the southern two-thirds of Northern Territory and the northwestern quarter of South Australia. They are found 1) as far south as Copper Hills, South Australia, 2) as far north as Fish River Gorge Block National Park, Northern Territory, as far east as the western edge of the Simpson Desert and as far west as the Gibson Desert. They occupy the northern fringes of the Great Victoria Desert, and the southern and eastern outskirts of the Gibson Desert in Western Australia. Beyond that they and Rory Cooper's false antechinuses (Pseudantechinus roryi), are found in the Pilbara Uplands stretching towards the coast with their western range ending with the Indian Ocean. In 2010, was an isolated population was detected in Queensland along the eastern fringes of the Simpson Desert. There are presumably isolated populations located on Barrow Island and the North West Cape peninsula. Also, in Western Australia, there are |=|

Fat-tailed false antechinuses are habitat specialists. Restricted to arid regions, they are primarily found within rocky habitats. Microhabitats can include crags, cliffs, breakaways, talus slopes and scree fields, sandstone outcrops, granite rock piles, and stony hills. They also live in or around termite mounds, especially within the red sandplains of the Tanami and western Simpson deserts. |=|

Fat-tailed false antechinuses not endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Fat-tailed false antechinuses appear to be relatively common in suitable habitats and those . A significant portion of their range is located in Australian national parks or other protected areas.

Fat-Tailed False Antechinus Characteristics and Diet

Fat-tailed false antechinuses range in weight from 17 to 45 grams (0.6 to 1.6 ounces) and range in length from 14.3 to 19 centimeters (5.63 to 7.48 inches), including the tail. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is only slightly present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. Adult males weigh 19 to 45 grams (0.7 to 1.6 ounces) and adult females weigh 17 to 40 grams (0.6 to 1.4 ounces). Males have a head and body length of 8.3 to 10,5 centimeters (3.3 to 4.1 inches) and females have a head and body length of 7.7 to 10.5 (3 to 4.1 inches).The tails of males tails measure 6.6 to 8 centimeters (2.6 to 3.1 inches). The tails of males tails measure 6.6 to 8.5 centimeters (2.6 to 3.3 inches). Males have an additional penile appendage, whose function is unknown, and females always have six teats. [Source: Christopher Wozniak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Fat-tailed false antechinuses possess a sparingly-furred “carrot”-shaped tail that is shorter than the body similar other dasyurid marsupials. Their tail — the source of their common name — is wide at the base and tapers off. Fat is stored in the tail. The fur of their back can range from gingery brown-grey to an orange-red color. The fur on their belly is whitish. Their carnivorous status of fat-tailed false antechinuses is reflected in their dental characteristics. They have a dental formula of 4124/3124 and sharp incisors. They possess two less pronounced premolars, compared to three premolars of other dasyurids. Their sharp snout could be an adaption to hunting insects.

Fat-tailed false antechinuses are recognized as carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and insectivores (eat insects). They consume a wide variety of insects, particularly termites, beetles and grasshoppers, followed by butterflies and invertebrate larvae. In total, 10 orders of insects have been identified as prey. Fat-tailed false antechinuses also opportunistically consume terrestrial invertebrates as well as spiders (Arachnida), snails (Gastropoda) and woodlice (Malacostraca). Fat-tailed false antechinuses have been observed eating rodents. It is not known whether they hunted the rodents or were eating carrion. A study of fecal pellet contents included termites (69 percent), beetles (63 percent), grasshoppers (42 percent), spiders (29 percent), and wasps/bees (28 percent). Additionally, unidentifiable invertebrate larvae were found in 33 percent of examined fecal pellets.

Fat-Tailed False Antechinus Behavior

Fat-tailed false antechinuses are terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), more diurnal (active during the daytime) in the winter, motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and have daily torpor (a period of reduced activity, sometimes accompanied by a reduction in the metabolic rate, especially among animals with highmetabolic rates). The mean home range of fat-tailed false antechinuses is 0.76 hectartes (1.9 acres); for mailes it about one hectare (2.5 acres) or more; for females it 0.31 hectares (0.76 acres). [Source: Christopher Wozniak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Fat-tailed false antechinuses primarily forage at night and during dawn and dusk. Like most dasyurids, they enter into a state of daily torpor to conserve energy and water loss. Their mean body temperature is around 35 degrees C, but during their daily torpor their average minimum temperature drops to 24.8 degrees C. The minimum recorded temperature in a female was 15.7 degrees C. |=|

Fat-tailed false antechinuses like to bask in the sun. During the Australian winter (May to August), they undergo torpor during the latter half of the night (instead of the day) and rewarm themselves during the morning by basking on rocks. They also forage immediately after rewarming, as well as closer to sunset. It has been suggested that these winter habits are present because fewer predators are active during the winter and foraging less risky. During the summer, they return to being nocturnal. Fat-tailed false antechinus have a more stable home range in comparison to other dasyurids in arid regions. Their rocky habitats provide sufficient shelter, sustainable food sources, and areas for burrowing, basking, and foraging, with no need for long range movements. Gilfillan has hypothosezed that these stable conditions result in an increased lifespans longevity for in comparison to other dasyurids of similar size.

Fat-tailed false antechinuses sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. The social interactions of fat-tailed false antechinuses are little studied, but in other small dasyurids, females exhibit mating squeaks that are reciprocated by males and followed by sudden movement. Tactile responses are common between a male and female while mating and between a female and her young in the pouch. |=|

Fat-Tailed False Antechinus Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Fat-tailed false antechinuses engage in seasonal breeding — once a year, in June and for eastern populations, and August and September for western populations. They are life-history strategy two breeders. This means females are monoestrous (breeding once annually during the Australian winter), and breed for three seasons. Males attempt to reproduce for two breeding seasons. Dasyurids are usually promiscuous, but specific mating habits of Fat-tailed antechinuses are not known. Females ovulate spontaneously, and mate either at the peak of their estrus cycle when they have the most body mass or shortly thereafter. Copulation can last 30 minutes to two hours. The gestation period ranges from 45 to 55 days. The number of offspring ranges from five to six.[Source: Christopher Wozniak, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by females. After birth, young — which weigh around 12.3 micrograms and around was 3.8 millimeters in length — attach themselves to the teats in their mother’s pouch. Litter sizes are limted by the number teats — six. all females. The average weaning age is 14 weeks and the average time to independence is 14 weeks. On average males and females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age 11 months.

Unlike many dasyurids, in while males die after their first mating, male fat-tailed false antechinuses can survive for more than just a single breeding season. They can survive to reproduce in three breeding seasons but typically it is two season. Females can survive for four but usually three, seasons. Males are not involved in parental care.

At around 40 days after birth, young are left alone in the nest outside of their mother's pouch. The eyes of the offspring start to open at an age of 60 to 65 days, and at 70 days old, young are able to independently move from the nest. Juveniles look similar to adults, save for females lacking a fully-developed pouch and males possessing a smaller scrotal width than adults. Juveniles weigh less than 15 grams.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025