Home | Category: Animals / Marsupials

TASMANIAN WOLVES

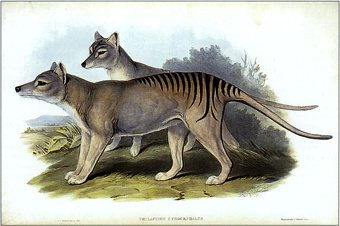

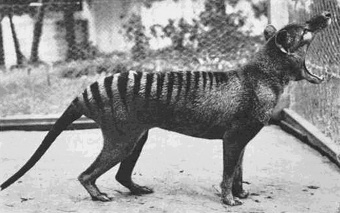

Tasmanian wolves (Thylacinus cynocephalus) are officially called thylacines and also known as Tasmanian tigers. They were carnivorous marsupial that were widespread in Australia and New Guinea and have been extinct since 1936 although reported sightings continue to this day. Tasmanian wolves are a symbol of Tasmania — they are on the official coat of arms of Tasmania — and are one of the most recognized extinct animals — and at top of the list of animals that people hope will one day be brought back to life.

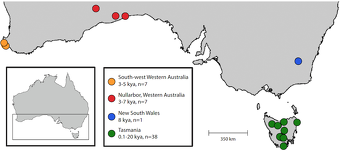

Tasmanian wolves died out in New Guinea and mainland Australia around 3,600 to 3,200 years ago, way before the arrival of Europeans, possibly because of the introduction of dingo, whose earliest record dates to around the same time, but which never reached Tasmania. Prior to European settlement, around 5,000 remained in the wild on the island of Tasmania. Beginning in the nineteenth century, they were perceived as a threat to the livestock of farmers and bounty hunting was introduced. The last known of its species died on September 7, 1936 at Hobart Zoo in Tasmania.

Tasmanian wolves were known as the Tasmanian tiger because of the dark stripes at the the top of their back, near their rear, and called Tasmanian wolves because they resembled a medium- to large-sized canids. At first Europeans called them zebra opossums. The name thylacine is derived from thýlakos meaning 'pouch' — a reference to their marsupial pouch. Both sexes had a pouch. The females used theirs for rearing young, and the males used theirs as a protective sheath, covering the external reproductive organs. A rear-opening pouch in females was seen as an advantage protecting the young when moving on four limbs through brush.

The closest living relatives of Tasmanian wolves are the other members of Dasyuromorphia family including the Tasmanian devil, from which it is estimated to have split 42 to 36 million years ago. Intensive hunting is generally blamed for the extinction of Tasmanian wolves, but other contributing factors were disease, the introduction of and competition with dingoes, human encroachment into its habitat and climate change. The remains of the last known Tasmanian wolves were discovered at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in 2022. Since extinction there have been numerous searches and reported sightings of live animals, none of which have been confirmed.

Book: “The History, Ecology and Loss of the Tasmanian Wolf” by Branden Holmes, an independent conservationist.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TASMANIAN WOLF EXTINCTION, SIGHTINGS, SEARCHES, BRINGING IT BACK ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVIL CONSERVATION: HUMANS AND THE DEADLY DISEASE RAVAGING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com

DASYURIDS AND DASYUROMORPHS (MARSUPIAL CARNIVORES) ioa.factsanddetails.com

NUMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLL SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SMALL MARSUPIAL CARNIVORE SPECIES: MULGARA, DIBBLERS, KULTARRS, NINGAUI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DUNNARTS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLANIGALES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANTECHINUSES: SPECIES, FALSE ONES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUICIDAL MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Uniqueness of Tasmanian Wolves and Love of them in Tasmania

"The Tasmanian wolf was completely unique among living marsupials," Andrew Pask, a professor of epigenetics at the University of Melbourne told Live Science. "Not only did it have its iconic wolf-like appearance, but it was also our only marsupial apex predator. Apex predators form extremely important parts of the food chain and are often responsible for stabilizing ecosystems."

Today, Tasmanian wolves have become a Tasmanian icon. They can be seen on billboards, postage stamps, license plates, buses, city emblems and the logo of the Tasmanian Cricket Association. The small town of Mole Creek in north-central Tasmania was once in the heart of Tasmanian wolf country. In the early 2000s, a popular place to see the animal is at the Wolf Bar on the main street of town. On the wall were dozens of Tasmanian wolves likenesses: drawings, footprints, articles, a fake fur and even a cartoon of Wolf Woods as a golfing Tasmanian wolves. [Source: Richard C. Paddock Los Angeles Times, November 21, 2004]

Brooke Jarvis wrote in The New Yorker: Like the dodo and the great auk, the Tasmanian wolf is more renowned for the tragedy of its death than for its life, about which little is known. Enthusiasts hope it will be a Lazarus species—an animal considered lost but then found. Nowadays, you can find the Tasmanian wolf on beer cans and bottles of sparkling water; one northern town replaced its crosswalks with wolf stripes. Tasmania’s standard-issue license plate features an image of a Tasmanian wolf peeking through grass, above the tagline [Source: Brooke Jarvis, The New Yorker, June 25, 2018]

Tasmanian Wolf Habitat and Where They Were Found

Fossils, archaeological findings or other evidence of Tasmanian wolves (kya means thousand years ago): A) Nullarbor, Western Australia (Red circles): 3,000 to 7,000 years ago; 2) New South Wales (Blue circle): 8,000 years ago; 3) Tasmania (Green circles): 100 to 20,000 years ago; The map likely illustrates the historical distribution and potential timelines of Tasmanian wolf existence and extinction [Source: Harvard University]

The original prehistoric range of Tasmanian wolves is thought to have extended throughout much of mainland Australia and New Guinea. This range has been confirmed by various cave drawings, such as those found by Wright in 1972, and bone collections that have been radiocarbon dated to 180 years before present. [Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The preferred habitat of Tasmanian wolves has never been thoroughly described but their remains have been collected throughout coastal regions of Australia and New Guinea. From the arrival of Europeans in 1803 until their extinction, Tasmanian wolves were found throughout Tasmania. They were most often seen in hilly country, resting during the day in forest and scrub, and hunting during the afternoon and evening in bordering thickets. Some descriptions suggest Tasmanian wolves were found in forested areas and grasslands. The last remaining populations were restricted to dense rainforests in Tasmania. Their dens were located mainly in hollow logs or rock outcroppings located in hilly areas that were adjacent to open areas, such as grasslands. |=|

Tasmanian Wolf Characteristics

Tasmanian wolves were the world's largest carnivorous marsupials. About the size of a German shepherd, they ranged in weight from 15 to 30 kilograms (33 to 66 pounds), stood up to 60 centimeters (two feet) at the shoulder and were of 1.23 to 1.95 meters (4 to 6.2 feet) long, including their 51-to-66 centimeter (20-to-26 inch) tail. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) was present: Males were slightly larger than females. Ornamentation was different. Based on individuals in captivity it is estimated that the lifespan of wild Tasmanian wolves was eight to 10 years. One lived in captivity until she was 12.6 years old. [Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tasmanian wolves have been described as "kangaroos masquerading as wolves." They had a dog-like head with a powerful jaw with 46 carnivorous-style teeth (four more than domestic dogs) but both males and females also possessed rear-opening pouches that in the case of females were used to raise young. Tasmanian wolves were sandy-yellow in color with 15 to 20 dark brown to grey stripes across their back which explains why they were sometimes called tigers and zebras. Although their head was nearly as large as a wolf's head, the brain of Tasmanian wolves was only one third the size. Their tail was stiff, thick and strong — almost kangaroo-like. They could open their jaws to an unusual extent. [Source: Anay Park, Smithsonian magazine, August 1988]

The body structure of Tasmanian wolves closely resembled that of wolves and other canids. Their was short and dense. The stripes began behind the shoulder blades, gradually increasing in both length and width. They had relatively narrow snouts with, on average, 24 sensory whiskers and whitish markings around the eyes, the base of the ears and the area around the upper lip. Their paws had non-retractable claws and they moved in digitigrade fashion (walking on their toes and not touching the ground with their heels, like a dog, cat, or rodent). They were capable of “sole walking," and bipedal hopping, similar to that of kangaroos. Both sexes had a pouch. The females used theirs for rearing young, and the males used theirs as a protective sheath, covering the external reproductive organs. The female pouch was located by the tail and had a fold of skin covering the four mammae. |=|

They resemble wolves, jackals and other canids found in other areas of the world and thus are an example of convergent evolution. But Tasmanian wolves were clearly related to the dasyuromorphs (the marsupial family that contains Tasmanian devils, quolls and small marsupial carnivores), based on morphological and molecular evidence. But they had teeth like dogs — long canines, shearing premolars, and grinding molars. The dental formula was 4/3, 1/1, 3/3, 4/4 = 46. Tasmanian wolves differed from other dasyuroids most conspicuously in their size and body form and long, canid-like limbs. [Source: Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Tasmanian Wolf Food and Eating Behavior

Tasmanian wolves hunted mainly at night alone or possibly in pairs. Studies and anecdotal evidence suggest that they were solitary ambush predators specializing in hunting small- to medium-sized prey. They preyed on other marsupials, including Tasmanian devils, wallabies, possums, as well as rodents, birds and shellfish. They also reportedly took sheep and stored and cached food. [Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The most commonly recorded mammalian prey of Tasmanian wolves were red-necked wallabies, Tasmanian pademelon and the short-beaked echidna. Other probable native mammalian prey were bandicoots, brushtail possums, as well as native rodents like water rats. Following their introduction to Tasmania, European rabbits rapidly multiplied and became abundant and there are reports of Tasmanian wolves preying on them. Some accounts also suggest that they may have preyed on lizards, frogs and fish. Waterbirds were the most commonly recorded bird prey, with historical accounts of Tasmanian wolves preying on black ducks and teals. Coots, Tasmanian nativehens, swamphens, herons (Ardea) and black swans were also likely preyed on They may have also preyed upon the now extinct Tasmanian emu. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tasmanian wolves consumed of hedgehog-like echidnas even though they were covered with spines. Tasmanian wolf dens have been discovered that were half filled with bones, including those of livestock animals such as calves and sheep. It is possible these animals were scavenged although its seems unlikely). According to witnesses Tasmanian wolves only ate what they killed and never returned to the site of a kill.

Tasmanian wolves were described as being strong and possessed good endurance. Some sources suggested that Tasmanian wolves tracked their prey considerable distances until their prey was fatigued, and then capture it with a sudden bust of energy. A close look at livestock kills, revealed Tasmanian wolves at least sometimes consume only specific parts of the animal such as such the liver, kidney fat, nasal tissues, and some muscle tissues. Such habits gave rise to the myth that they preferred to drink blood. There were very few documented Tasmanian wolf attacks on humans and many of these were provoked, generally occurring when Tasmanian wolves were startled by light or rapid movements, or were cornered.

Tasmanian Wolf Behavior

Tasmanian wolves were terricolous (lived on the ground), troglophilic (lived mostly in caves), saltatorial (adapted for leaping), motile (moved around as opposed to being stationary) and nomadic (moved from place to place, generally within a well-defined range). Their lairs were usually in rocky caves or hollows at the base of eucalyptus trees. [Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

In the 1920s, Le Souef and Burrell observed that while pacing, Tasmanian wolves held their head low like that of a scenting hound and paused abruptly to monitor their surroundings with their head held high. They also noted that captive animals were fairly docile around humans; paying little attention to them when humans cleaned cages with Tasmanian wolves in them. It was speculated that was because Tasmanian wolves were blinded by the sunlight as they usually spent their days in the darkness of their lairs. There were reports that Tasmanian wolves curled up like dogs when they slept and occasionally basked in the sun. There were also reports that Tasmanian would lie on their side fully extended, with their upward ear fully erect. |=|

As for how they moved around, in 1863 Gunn noted a female Tasmanian wolf once jumped effortlessly to the top of her cage rafters, a distance of two to two and half meters (sexi to eight feet) in the air. Moeller described how at slow speeds Tasmanian wolves had a plantar walk, common to most mammals, where diagonally opposite limbs move alternatively, except that Tasmanian wolves they would use their entire foot, with their the long heel touching the ground. This method was not well suited for running. Tasmanian wolves were observed loping around their pen with only the pads of their feet touching the floor and using a kangaroo-like, bi-pedal hop for short distances, in which they stood on their hind limbs with their front limbs in the air, using their tail for balance.

Tasmanian wolves communicated with vision, touch and chemicals usually detected by smelling and sensed using vision, touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. The skulls of Tasmanian wolves have enlarged sinus cavities suggesting they had good senses of smell. Since they hunted at night it is assumed they had good night vision or relied on senses other than vision in the dark. Tasmanian wolves had vibrissae (whiskers) on their muzzle similar to those on wolves and were probably used in detecting prey somehow. Gould noted in 1863 that when disturbed, Tasmanian wolves dash about making short guttural cries that were almost like barks. Le Souef and Burrell in 1926 said that when excited Tasmanian wolves made a series of husky, coughing barks, wheezing when they inhaled. [Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tasmanian Wolf Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Tasmanian wolves engaged in seasonal breeding. They may have bred twice each year and may have had a four-month-long breeding season, although the timing may have been variable. The number of offspring ranges from two to four. The gestation period is unknown, but is usually pretty short — around a month — in marsupials, with much of the development of young taking place in the pouch. It is thought that the young in the pouch for about three months and remained with the mother for another six months.[Source: Paul Treu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tasmanian wolves were elusive animals and their mating patterns are not well-documented. Guiler (1926) speculated about breeding behaviors based on bounty records. He documented that only one pair of male and female adult Tasmanian wolves were ever captured or killed together and concluded that Tasmanian wolves only came together for mating and were otherwise solitary. Some say this hints they were monogamous. |=|

Based on the bounty data, Guiler (1961) determined “half growns” (and their mothers) were taken during every season, the highest numbers of post pouch young were taken in May, July, August, and September. He estimated that the breeding season lasted approximately four months and was separated by a gap of two months. It is thought that female Tasmanian wolves began breeding in autumn and could have a second litter of young after the first was weaned. Other sources indicate births may have occurred continuously throughout the year but were concentrated in the summer months in December-through March.

Parental care by Tasmanian wolves was provided by females. Young were altricial, meaning they were relatively underdeveloped at birth. There was an extended period of juvenile learning. The rear-opening pouch of females pouch was located by the tail and had a fold of skin covering four mammae that could accommodate up to four young. Tasmanian wolves were observed caring for three to four young carried by the mother’s pouch until they were too big to fit there. While in the pouch, young nursed on her four teats. Juveniles are thought to remain with their mothers until they were at least half grown.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025