Home | Category: Marsupials

NUMBATS

Numbats (Myrmecobius fasciatus) are also known as the noombats and walpurti. Attractive animals that have a long snout and look like a cross between a mouse, fox and raccoon, they are are small, rat-size marsupials that are unique in that they don't have a pouch and are not nocturnal. They feed primarily on termites. Adults about half a kilogram (1.1 pounds) and have reddish gray fur and six or seven white strips across rear era of their back. The numbat is the faunal emblem of Western Australia.

Numbats were once widespread across southern Australia, but are now restricted to several small colonies in Western Australia as a result of habitat destruction and predation by the introduced red foxes. They are currently listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and the US Fish & Wildlife Service as an Endangered species. Numbats have been recently re-introduced to fenced reserves in South Australia and New South Wales.

Numbats are the only species in the family Myrmecobiidae. They make their homes primarily in hollow, fallen wandoo trees and feed on ants and termites with their long sticky tongue like anteater. Numbats, aardvark of Africa. pangolins of Asia and Africa and anteaters of South America all have long sticky tongue used for collecting ants. These species, all from different animal groups, developed their tongues independently. Numbats, quolls and Tasmanian devils are small predators that are classified as Dasyuromorphs (predatory marsupials).

The average lifespan numbats in the wild is four to five years, compared to seven years for females and eleven years for males in captivity. One of the main reasons for this The reason The lifespan for those in the wild is quite short because numbats are often preyed on by foxes, raptors, and cats. Numbuts expend a lot of energy to avoid predators. Captive-bred numbats released in the wild, they lack the basic knowledge and skills to avoid their predators and often killed not long after they are released in non-fenced areas.

RELATED ARTICLES:

DASYURIDS AND DASYUROMORPHS (MARSUPIAL CARNIVORES) ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLL SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVIL CONSERVATION: HUMANS AND THE DEADLY DISEASE RAVAGING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLF EXTINCTION, SIGHTINGS, SEARCHES, BRINGING IT BACK ioa.factsanddetails.com

SMALL MARSUPIAL CARNIVORE SPECIES: MULGARA, DIBBLERS, KULTARRS, NINGAUI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DUNNARTS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLANIGALES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANTECHINUSES: SPECIES, FALSE ONES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUICIDAL MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Numbat Habitat and Where They Are Found

Since the arrival of Europeans, the number of numbats has declined dramatically and now they are extinct in approximately 99 percent of their former range. Previously they occupied most of southern Australia, including New South Wales and Victoria, and parts of Western Australia and the Northern Territory, Only two natural populations remain — at the 1) Dryandra and 2) Perup sites — both in Western Australia. Reintroduced populations can be found in 1) Western Australia in Dragon Rocks Nature Reserve, Batalling State Forest, Tutanning Nature Reserve, and Boyagin Nature Reserve; 2) in South Australia in Yookamurra Sanctuary and 3) in New South Wales and Scotia Sanctuary (located in New South Wales). [Source: Angelique de la Riva, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

When numbats were abundant, they occupied semi-arid and arid woodlands (composed of flowering trees and shrubs of the genera Eucalyptus and Acacia) and grasslands (composed of grasses of the genera Triodia and Plectrachne). Now, they can only be found in eucalypt woodlands, which are located at an elevation of approximately 317 meters (1040 feet) in the wettest periphery of the former range because of the abundance of old and fallen trees.

The logs of eucalypt woodlands play an important role helping numbats survive. At night, numbats seek shelter inside hollow logs, and during the day, numbats can avoid predators, especially birds and foxes, by staying hidden within the darkness of the logs. During mating seasons, logs provide numbats an area for their nesting sites. Most importantly, the heartwood of the majority of trees in eucalypt woodlands are eaten by termites, which make up a large portion of the numbat's diet. The presence and availability of termites is so vital to numbats that numbats are only found where termites are found. If areas are too wet or too cold, termites do not thrive, and, thus, neither do numbats.

Numbat Characteristics

Numbats are small, slender carnivorous marsupials. They range in weight from 300 to 752 grams (10.6 to 26.5 ounces) and have a head and body length of 17.5 to 29 centimeters (6.9 to 11.4 inches), with their average length being 27 centimeters (10.63 inches). Their bushy tail is 12 to 21 centimeters (4.7 to 8.3 inches). Their average basal metabolic rate is 0.389 cubic centimeters of oxygen per gram per hour. Their average basal metabolic rate is 0.907 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Females weigh between 320 and 678 grams (11.3 to 24 ounces) , averaging 478 grams (16.9 ounces), and males weigh between 300 grams and 715 grams (10.6 to 25.2 ounces), averaging 597 grams (21 grams). [Source: Angelique de la Riva, Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The head of numbats is relatively small and flat with an elongated, pointed snout, and small ears. Numbats have a remarkable long and slender tongue, and a slim, sticky tongue that is capable is sticking out at least 10 centimeters. with which they extract termites and ants from their nests. The eyes and ears are located high on the head, and the erect ears are twice as long as broad. Large, strong claws are found on all digits. The forefeet have five toes and the hind feet have four toes. Female numbats do not have a proper pouch; instead they have skin folds, which are covered in short crimped, golden hair and have four nipples on the abdomen from which young nurse.

The coat of numbats is distinctively banded across the back and rump with four ro eleven transverse dark and white stripes. Each individual has a unique, distinct appearance The coat is composed of short, stiff, reddish-brown or grey-brown hair. A single dark stripe, accentuated by a white band below it, crosses each side of the face and travels through each eye. The hair on the tail tends to be slightly longer than the hair on the body. Tails tend to be brown in color interspersed with white with an orange-brown color on the underside. The hair on the belly numbats are white.

Unlike other mammals, numbats do not have proper teeth but instead have blunt “pegs” because they do not chew their food. These “pegs” are relatively small. There are four upper and three lower incisors on each side of their jaws. Following these are upper and lower canines, and behind the canines are a series of molars and premolars that may include extra (supernumerary) teeth. The total number of cheek teeth is usually 7-8 on each side of the upper jaw, 8-9 on each side of the lower.As is true of other dasyuromorphs, numbats toes are not fused together. According to Animal Diversity Web: Cranial characteristics of these peculiar animals include an unusual backward prolongation of the hard palate, reduction in the size and number of palatal vacuities, massive postfrontal processes, and palatal branches of the premaxillae that don't fuse anteriorly. |=|

Numbat Food and Eating Behavior

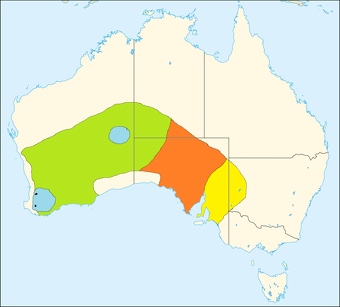

Historical range map of numbats with extinctions: A) from 1800 to 1910 (yellow); B) from 1910 to 1930 (orange); C) from 1930 to 1960 (green); and D) 1960 to 1980 (blue), and their remaining range shown in black

Numbats are primarily insectivores (eat insects) and are also recognized as carnivores (eat meat or animal parts). Their diet consists primarily of termites, although they ingest some ants they prey on termites, by accident while eating termites. They eat approximately 15,000 to 20,000 termites per day, which is roughly equal to about 10 percent of the body weight of an adult numbat. [Source: Angelique de la Riva, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Numbats have several morphological features that are adaptions to obtaining and feeding on termites. The elongated snout is used for getting into logs and small holes in the ground where termites lurk. Their nose is extremely sensitive, enabling them to sense the presence of termites by smell. They can also sense vibrations in the ground. The numbats long, thin tongue, which is coated with sticky saliva, allows numbats to gain access to the termite passageways, also known as galleries, and quickly withdraw several termites that have stuck to the saliva. The saliva is produced by a pair of quite enlarged and complex salivary glands. The forefeet and hind feet have razor-sharp claws, which allow numbats to dig rapidly into termite galleries in the soil. Their mouths are filled with 47 to 50 blunt "pegs," instead of proper teeth as in other mammals, because numbats do not chew the termites.

Numbats often forage during the day. In "Fauna of Australia," (1960) J.A. Friend and J.H. Calaby (1960) say numbats use scent to locate termite galleries and begin to dig out the insects with both feet rapidly. Numbats use their tongue to pick up exposed termites and may leave to find another gallery or dig in the same gallery once termites are no longer exposed. Numbats also turn over leaves and sticks with their teeth to expose and prey upon termites.

The termites that numbats feed on includes ones in the genera Heterotermes, Coptotermes, Amitermies, Microcerotermes, Termes, Paracapritermes, Nasutitermes, Tumulitermes, and Occasitermes. This is at least partly because they are among the most commin ones. Coptotermes and Amitermies are the most common termite species in numbat habitat, and thus it is no surprise they are the most commonly eaten. Individual numbats have preferences; some lactating females prefer Coptotermes species at certain periods of the year, and some numbats have refused to eat Nasutitermes species during the winter.

Numbat Behavior: Daily Activities, Sociability

Numbats are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), diurnal (active during the daytime), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range) Numbats are very unusual marsupials in that they are diurnal. They are active during the day because of their termite diet. Because numbats are not powerful enough to break into termite mounds, they have to feed on them when they are more active and likely to go outside the mounds or be in parts of the mound where numbats cn reach, which is during the day. [Source: Angelique de la Riva, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Their average territory is an individual home range of approximately 50 hectares (123 acres). Members of the same sex generally do not have overlapping territories but males and females sometimes do. Numbats shelter at night in hollow logs and burrows, or nests composed of bark, grass, and leaves at times and often have a large number of these shelters within their home range. Numbats tend to shelter in logs that area approximately eight centimeters in diameter. Their burrows have a straight shaft about one meter long, 15 to 23 centimeters in diameter, and 10 to 60 centimeters below ground. These logs and burrows are good places to shelter, providing stable temperatures, humidity, and other environment conditions even when it is very hot and dry outside or cool.

Numbats are generally solitary animals, except for mothers with young and males and females sharing a nest temporarily during the breeding season. Young numbats in the same a litter play with one another, running and chasing until they reach 10 months of age. Once they leave the home range, they establish their own territory, which they maintain for life. Numbats exhibit seasonal patterns related to prey abundance, and reproduction. During the spring and summer seasons, they are active for a longer periods of time, roaming around and feeding in mid-morning and in the late afternoons, taking only a short "rest" during mid-day they shelter in a hollow log. During autumn and winter, numbats are active later in the morning and returns to their shelter earlier in the afternoon, staying active during mid-day.

When numbats move around, they walk or trot with jerky movements. Occasionally they stop to feed, while continuing to scan their surroundings for predators. When they sit, they do so in a vertical position on their hind feet, with their forepaw raised in alert. When excited or stressed, numbats arche their tail over their back and erect their fur. When disturbed or threatened, they flee using a a bounding run, reaching speeds up to 32 kilometers per hour (20 miles per hour), until they reache a hollow log or burrow. After pausing briefly to look into the shelter before entering it, numbats press their body firmly against the inner wall and grasps the sides with their claws to prevent any attempt of extraction. Once the threat has passed, they come out of hiding head first and continue on. |=|

Numbat Senses, Communication and Predator Responses

Numbats sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also leave scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Numbats rely heavily on sight, hearing, and smell. They are constantly on alert when roaming around and feeding. They detect threats from predators primarily by sound (hearing the predator's approach) and vision (seeing their approach). When feeding, numbats mainly use smell to locate termite galleries. They are about detect galleries up to five centimeters below the ground surface. Smell is also used during the breeding season. When male finds a receptive female, he smears an oily, foul-smelling substance from his sternal gland around the female numbat's territory, which wards off other males. [Source:Angelique de la Riva, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Angelique de la Riva of Animal Diversity Web wrote: Numbats produce a variety of vocalizations. During breeding season, if a female and male are both interested in one another, they vocalize by producing a series of soft clicks. However, if a male approaches a female and she rejects his advances, she will produce growling vocalizations that may lead to loud altercations. A similar vocalization that resembles these growling sounds can also be heard from numbats that are being handled or disturbed. Differing slightly, these distressed low-throaty growls are produced with the mouth closed, along with a repetitive "tut tut tut." Another type of vocalization is the hissing growls produced by numbats that are protecting their territory against foreign numbats. Besides the breeding season and stressful situations, the only other time one tends to hear vocalizations produced by numbats are when a mother is caring for her young. Once the young have emerged from the log or burrow, the mother communicates with them by soft chirping sounds. |=|

The three main predators of numbats are red foxes, raptors, and feral cats. Because of their small size, numbats are easy prey for these predators. Even the smaller species of raptors, such as little eagles, which are about half a meters in size can easily kill numbats. It is also possible that numbats are taken by snakes, such as carpet pythons, and large lizards, such as sand goannas. Many of the predators that prey on numbats thrive fragmented woodlands and have contributed to rapid decline of numbat populations in such ares. Numbat predator avoidance adaptations include camouflage (their fur patterns blend in well with the surrounding bush); and erect ears located high on the head and the eyes located on the opposite sides of their head allow numbats to hear or see predators coming towards them from different locations. If numbats sense danger or encounter a predator, they freeze and keep very still until the danger has passed. If pursued, numbats run to shelter and grasp the sides of the enclosure. At times, numbats may also try to ward off predators by producing low-throaty growls along with a repetitive "tut tut tut."

Numbat Mating and Reproduction

Numbats are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding, which takes place from December to January. Females have an estrus cycle, which is similar to the menstrual cycle of human females and are polyestrous, which means they have several estrus cycles during a single breeding season. This means that females who have failed to conceive or have lost their young may conceive again and that during a single breeding season females may breed several times or just once if initially successful. Males too have a fertility cycle. Sperm appear in early December, declines in February, and is gone by March. Females first breed when they are 12 months of age, and males are sexually mature at 24 months. The average gestation period is only 14 days. The average number of offspring is four.[Source: Angelique de la Riva, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

As the mating season starts male numbats secrete an oily substance from their sternal gland at the top of the chest. Turning their fur red, this pungent oil is rubbed over surfaces of logs and rocks by the male. In addition to advertising to females that the male is looking for a mate, the smell also warns other males to stay away from his territory. When a male desires a certain female, he follow her and lavishes attention to her cloacal region by sniffing it.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Both the male and female vocalize to each other, producing soft clicking sounds. Numbats vocalize only during two different periods in their life (during the breeding season and during infancy when communicating with the mother); however, breeding vocalizations are significantly different than baby numbat vocalizations. If a female rejects male advances, loud altercations will take place. The female will produce low, throaty, aggressive growls with her mouth closed. At times, the male will attempt to mount the aggravated female, which will lead to them tumbling together on the ground with the female growling. The male may still try to pursue the female by chasing her, or he may stop his advances all together.

After copulation, which ranges in time from less than one minute to an hour, the male may leave immediately in order to mate with another female, or he may stay in the until the mating season ends. However, after the reproductive season finishes, the male will leave the female. The female then cares and tends to the young by herself.

Numbat Offspring and Parenting

Parental care by numbats is provided by females. Males are not involved in parenting. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Female don’t have pouches; instead they have skin folds, which are covered in hair and have four nipples from which young suckle. The average weaning age is nine months and the average time to independence is 11 months. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age 12 months and males do so at 24 months. [Source: Angelique de la Riva, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Female numbats typically give birth to four young in January or February in a den in a hollow log or burrows on a nest composed of bark, grass, and leaves. The underdeveloped young , which are about two centimeters long, travel to the mother's nipples. The four nipples are covered by crimped, golden hair that differs greatly from the long white hair on her chest. There, the young entwine their forelimbs in the crimped hair and each attach themselves a different nipple for up to six months. By that time young have grown so large that the mother cannot walk properly. By late July or early August, the young are detached from the nipples and are placed in the nest. In late September, the young begin to forage for themselves, becoming independent and moving to a territory of their own by November.

Newborn numbats vary in size from two to 7.5 centimeters. The snout is extremely shortened. When the young reach the length of approximately three centimeters, a light downy coat begins to appear, and this coat eventually bears the characteristic white stripes when the numbat is about 55 millimeters in length. After the young detach themselves from the nipples and are ensconced in the nest, the mother periodically returns to the log or burrow to suckle them until they are eight or nine months of age. After this, young begin to investigate the area outside their nest and eating termites. The mother weans them from her milk between ten and eleven months of age.

Numbats, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List numbats are listed as Endangered; On the U.S. Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. Numbat populations have decreased steadily since the arrival of Europeans in the late 1700s and declined by more than 20 percent in five years between the years 2003 and 2008. It is is currently estimated that are are around 1,000 numbats in the wild — mostly in two natural sites — Dryanda and Perup of Western Australia — and several places they have been relocated (see Where Numbats Are Found at the beginning of the article). In Dryanda, populations have to decreased dramatically for unknown reasons, declining from an estimated peak of 600 in 1992 to 50 in 2012. In Perup, populations are stable and possibly increasing in number. In reintroduced sites, there were 500 to 600 numbats in the early 2010s and populations seemed stable but were not self-sustaining and, not considered secure. [Source: Angelique de la Riva, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Numbats used to flourish throughout Southern Australia, parts of Western Australia, and the Northern Territory. Aboriginals called them "walpurti" and hunted them for food by chasing the numbats into their burrows or logs and digging them out by hand. Now numbats are protected and hunting them is banned.

Numbats are hunted by natural predators such as raptors but it is believed that introduced predators, namely red foxes and feral cats, played a big part in their decline. The deliberate release of the European red fox in the 19th century is is presumed to have wiped out the entire numbat population in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory, and almost all numbats in Western Australia. The introduction of rabbits and rats may also have also contributed to the numbat decline. Loss of habitat is also blamed. Changed fire patterns and habitat destruction in some areas have reduced the number of logs, which numbats use as shelter and are home to termites, the primary food source of numbats.

A number of programs — both government and privately funded — have been set up to help numbats. These include captive breeding, reintroduction programs, protecting areas with fences and other means, and controlling red fox and feral cat populations. Objectives for recovery include increasing the number of self-sustaining populations to at least nine and the number of individuals to over 4,000. Captive breeding and re-introduction programs present challenges as numbats that have been re-introduced to wild are often easily killed by predators. In the early 2000s, the Perth Zoo implemented an experimental training program where young captive-bred numbats were exposed to a raptor while loud noises and bird alarm calls were sounded. These trained numbats had a higher survival rate after release in the wild than the untrained numbats. Dur primarily to fox-and-cat-control programs the mortality rates of numbats in the wild had dropped to a fairly low rate as of the early 2010s.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025