Home | Category: Animals / Marsupials

TASMANIAN DEVILS

Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) are poodle-size predators that are classified along with quolls as Dasyurids (predatory marsupials). Fierce, nocturnal and generally solitary, they have a black body with a white stripe across the front of the chest. The are about 60 centimeters (two feet) long, excluding their 35-centimeter (1.2-foot) -long tail. It has been said that their teeth are sharp enough to devour a horse, bone and all, and they reek of death, hence their name. Tasmanian devils were previously known by the scientific name Sarcophilus laniarius

Tasmanian devils are a nasty little critters not unlike the Warner Brothers cartoon character by the same name except they are smaller. Young Tasmanian devils like to wrestle. Adults often fight off other Tasmanian devils. They have the loudest vocalizations of all marsupials and are arguably the smelliest. They make long whining snarls and a sniffing noise. They are called "devils" due to the eerie, guttural growls and screeches they make, especially when threatened or during feeding, that so unnerved early European settlers in Tasmania they thought the sounds had to have been made by something demonic.

Tasmanian devils are primarily scavengers. They feed on carcasses (one reason they have a reputation for smelling bad) and are known to eat tiger snakes, one of the world’s most venomous snakes, on occasion. They also eat insects and small birds and mammals. Their habit of eating roadkills sometimes leads to them becoming roadkills. Tasmanian devils rarely live over of five years of age in the wild. Most young die immediately after dispersing out of their natal range as a result of food scarcity or competition. They have lived over eight years in captivity.

Tasmanian devils for the most part are found only in Tasmania, although fossil evidence suggests that they once roamed much of the Australian mainland and they have been re-introduced to the Australia mainland in a few places. Tasmanian devils are found throughout Tasmania except in areas where there has been extensive habitat fragmentation and deforestation. They are most numerous in coastal heath and rangeland areas where agricultural practices maintain a constant supply of carrion. They also occur in open, dry schlerophyll (hard leaf) forest and mixed schlerophyll rainforest. Their dens typically are located in hollow logs, caves, or burrows. [Source: Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tasmanian devils became extinct on the mainland of Australia around 3,500 years ago and became largest carnivorous marsupial in the world following the extinction of the Tasmanian wolf (thylacine) in 1936. Tasmanian devils belongs to the family Dasyuridae. Their genus, Sarcophilus, contains two other species, known only from fossils from the Pleistocene Period (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). Genetic and morphological analysis indicates that Tasmanian devils are most closely related to quolls. It has been suggested that their absence in many previously occupied areas is the result of competition from introduced dingoes. [Source: Wikipedia]

Book: Tasmanian Devil: A Unique and Threatened Animal by David Owen and David Pemberton (Allen & Unwin, 2006)

RELATED ARTICLES:

TASMANIAN DEVIL CONSERVATION: HUMANS AND THE DEADLY DISEASE RAVAGING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLF EXTINCTION, SIGHTINGS, SEARCHES, BRINGING IT BACK ioa.factsanddetails.com

DASYURIDS AND DASYUROMORPHS (MARSUPIAL CARNIVORES) ioa.factsanddetails.com

NUMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLL SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SMALL MARSUPIAL CARNIVORE SPECIES: MULGARA, DIBBLERS, KULTARRS, NINGAUI ioa.factsanddetails.com

DUNNARTS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLANIGALES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANTECHINUSES: SPECIES, FALSE ONES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUICIDAL MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Tasmanian Devil Characteristics

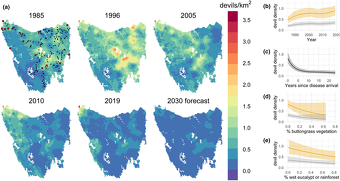

Tasmanian devil distribution: Past and predictive maps of Tasmanian devil density from the joint likelihood model; Devil densities were rising before the discovery of devil facial tumour disease( DFTD) in 1996; The spread of DFTD across Tasmania then caused a wave of rapid and severe population declines; In the first panel, black dots indicate the location of annual spotlight transects and maroon squares show the location of longitudinal trapping sites, from Researchgate

Tasmanian devils range in weight from four to 12 kilograms (8.8 to 26.4 pounds). They have a head and body length of 52.5 to 80 centimeters (20.7 to 31.5 inches), with a 23-to--30-centimeter (9-to-12-inch) tail. Large males stand 30 centimeters (one foot) at the shoulder. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Male weigh from 5.5 to 12 kilograms (8.8 to 26.4 pounds) and females weight from 4.1 to 8.1 kilograms (9 to 18 pounds). Females have four mammae and, unlike many other dasyurids, the marsupial pouch is completely closed when breeding. Males have external testes in a pouch-like structure[Source: Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|; Wikipedia]

Tasmanian devils are stocky and have brownish black fur, with a white throat patch, white spots on their sides and backside, non-retractable claws and a pinkish snout. The white markings suggest that devils are most active at dawn and dusk, and they aim to draw biting attacks toward less important areas of the body, as fighting between devils often leads to a concentration of scars in that region. An ano-genital scent gland at the base of its tail is used to mark the ground behind the animal with its strong, pungent scent. Unusually for marsupials, the forelegs of Tasmanian devils are slightly longer than their hind legs. Devils have five long toes on their forefeet, four pointing to the front and one coming out from the side, which gives them the ability to hold food. Body size varies considerably with diet, habitat, and age. Fat storage occurs in the tail, as in many dasyurids. healthy devils have fat tails.

The large head and neck of Tasmanian devils and well developed jaw muscles allow them to generate among the strongest bites per unit body mass of any living predatory land mammal. Molar teeth are heavy and adapted for their role in crushing bone and tearing through muscle and thick skin. The teeth and jaws of Tasmanian devils resemble those of hyenas, an example of convergent evolution. The large neck and forebody of Tasmanian devils gives them their strength but also causes this strength to be biased towards the front half of the body, resulting in the animal’s lopsided, awkward, shuffling gait.

In 2020, the Toledo Zoo reported that Tasmanian devil glow under a blacklight. “Biofluorescence refers to the phenomenon by which a living organism absorbs light and reemits it as a different color,” the zoo wrote on Facebook. “In the case of the Tasmanian devil, the skin around their snout, eyes, and inner ear absorbs ultraviolet light ... and reemits it as blue, visible light.” University of Kansas biologist Leo Smith, an expert in biofluorescence, told NPR it was not clear what purpose the trait served in mammals. “It’s not something that you can necessarily come up with a really good explanation for why it might be there or what could be the advantage. Like a lot of things just evolve and they’re not good or bad, they’re just whatever,” Smith said.[Source: Josephine Harvey·Reporter, Huffington Post, December 15, 2020]

Tasmanian Devil Diet and Food

Warner Bros, Looney Tunes Tasmanian Devill first appeared in 1954 and voiced by Mel Blanc from 1954 to 1989

Tasmanian devils are primarily carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and scavengers. Animal foods include mammals amphibians, reptiles, carrion, insects, and non-insect arthropods such as spiders. Among the plant foods they eat are roots, tubers and fruit. Tasmanian devils On average, devils eat about 15 percent of their body weight each day, but have have been known to eat 40 percent of their body weight in 30 minutes. Their jaws are incredibly strong — stronger than those of a fox, which is five times their size. [Source: Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|; Wikipedia]

Wombats are favorite prey animals because they are easy to kill and have high fat content. Other animals that Tasmanian devils have been recorded eating are wallabies, bettong, potoroos, sheep, rabbits), birds (including penguins), fish, insects, tadpoles, frogs, insect larvae, snakes, and reptiles. Their diet is widely varied and depends on the food available. Tasmanian devils have been accused of being livestock predators and can bite through metal traps, and tend to reserve their strong jaws for escaping captivity rather than breaking into food storage. Tasmanian devils are known to hunt water rats by the sea and forage on dead fish that have been washed ashore. Near human habitation, they sometimes steal shoes and chew on them, and eat the legs of sheep that have slipped in wooden shearing sheds. Unusual stuff found in devil scats includes collars and tags of devoured animals, intact echidna spines, pencils, plastic and jeans.

Tasmanian devils are efficient scavengers, eating even bones and fur. In the past Tasmanian devils may have depended on carrion left from Tasmanian wolf kills. Tasmanian devils ate Tasmanian wolf joeys left alone in dens when their parents were away. This may have helped to hasten the extinction of Tasmanian wolves, which also ate Tasmanian devils. Tasmanian devils have forages corpses. In in one case they dug down to eat the corpse of a buried horse that had died due to illness. They are known to eat animal cadavers by first ripping out the digestive system, which is the softest part.

Tasmanian Devil Eating Behavior and Rowdy Group Feeds

Tasmanian devils generally feed around dusk and midnight. Although they are capably of taking prey up to the size of a small kangaroo, in practice they are opportunistic and eat carrion more often than they hunt live prey. Many of the large animals they eat — wombats, wallabies, sheep, and rabbits — are in the form of carrion. Devils are very cautious animals, often spending a lot of time checking out a food sources before taking actions. They forage in a slow, lumbering way, using their sense of smell and whiskers to find food at night. They are famous for their rowdy communal feeding, which is accompanied by aggression and loud vocalizations. [Source: Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|; Wikipedia]

Eating is a social event among Tasmanian devils. The combination of being a solitary animal that eats communally makes is devil unique among carnivores. Much of the noise attributed to Tasmanian devils is produced during their rowdy communal eating events, at which up to 12 individuals may gather, although groups of two to five are the norm common. The noise they devils make can is so loud it is it can often be heard several kilometers away. This has been interpreted as call to other devils come and share in the meal, so that food is not wasted by rotting. The amount of noise is correlated to the size of the carcass.

Tasmanian devils follow a system when they eat. Juveniles are active at dusk, so they tend to reach the source before the adults. Typically, dominant animals eats until they are satiated and leaves, fighting off any challengers that disturb them while eating. Defeated animals run into the bush with their hair and tail erect, their attackers pursue them and bite them in the rear. Disputes are less common when food is more plentiful.

Tasmanian Devil Behavior

Tasmanian devils are terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary. They can climb trees, which they more when they are young, and swim across 50-meter-wide rivers. Both males and females make nests of bark, grass and leaves which they inhabit during the day. Unlike most other dasyurids, Tasmanian devil thermoregulates effectively, and can be active during the middle of the day without overheating. They are sometimes seen sunbathing during the day in quiet areas.[Source: Wikipedia; Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tasmanian are usually solitary but from time to time gather at food sources (See Above) and sometimes defecate together in a communal location. At group feedings there is dominance hierarchy, that may a learned. When fighting, Tasmanian make a big racket — vocalizing with growls, screeches, and vibratos. A field study published in 2009 involving radio-collared Tasmanian devils indicated the devils were part of a single huge contact network, characterised by male-female interactions during mating season, female–female interactions at other times, but frequency and patterns of contact did not vary much between seasons. Males rarely interact with other males. As a result all devils in a region are part of a single social network.

Tasmanian devils can run at speeds of up to 13 kilometers per hour (8.1 mph) for short distances and can average 10 kilometers per hour (6.2 mph) for "extended periods" on several nights per week. There have been reports that devils can run at 25 kilometers per hour (16 mph) for 1.5 km (0.93 miles) and it has been conjectured that, before the arrival of European and the introduction of livestock, vehicles and roadkill, Tasmanian devils had to chase their prey to get food. Sometimes after they run for long distances they sit still for up to half an hour, something that has been interpreted as evidence of ambush predation.

Adult Tasmanian devils have few natural predators. It the past Tasmanian wolves preyed on them. Small Tasmanian devils may be preyed by eagles, owls and tiger quolls. When threatened the furless ears of devils turn red and they yawn, exposing fearsome teeth. Tasmanian devils put up a ferocious defense when attacked and can strike back with sharp teeth and powerful jaw muscles, allowing them to fend off predators much larger than themselves. Tasmania is still wild and relatively untouched by non native predators. There are some foxes up in Tasmania; .

Tasmanian devils can be quite shy. Zoologist Chris Coupland, at the Mole Creek Trowunna Wildlife Park in northern Tasmania, told Reuters the real devil is all bluff. Tourists are surprised by its small size, he said, and that they can enter a devil enclosure and not be torn limb from limb. "They have quite a high level of intelligence and recognition and the ones we handle are friendly," Coupland said. [Source: Wendy Pugh, Reuters, Apr 10, 2004]

Tasmanian Devil Home Ranges, Dens and Movements

The home range devils' ranges from four and 27 square kilometers (1.5 and 10.4 square miles), with an average of 13 square kilometers (five square miles. Their location and shape depends on the distribution of food, particularly wallabies and pademelons nearby. They are considered to be non-territorial in general, but females are territorial around their dens. This allows a larger number of devils to occupy a given area than territorial animals, without conflict. [Source: Wikipedia; Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tasmanian devils use three or four dens regularly. Dens formerly owned by wombats are especially valued as maternity dens because of their security. Dense vegetation near creeks, thick grass tussocks, and caves are also used as dens. Adult devils may use the same dens for life. It is believed that, as a secure den is highly prized, some may have been used for several centuries by generations of animals. Studies have suggested that food security is less important than den security. Young pups remain in one den with their mother, and other devils are mobile, changing dens every one to three days. I n areas near human habitation, they are known to steal clothes, blankets and pillows and take them for use in dens in wooden buildings.

Tasmanian devils travel a mean distance of 8.6 kilograms (5.3 miles) every night. However, there have been reports of them traveling as far as 50 kilometers (31 miles) per night. They choose to travel through lowlands, saddles and along the banks of creeks, particularly preferring carved-out tracks and livestock paths and eschewing steep slopes and rocky terrain. Devils typically make circuits of their home range during their hunts.

Tasmanian Devil Senses and Communication

Tasmanian devils have keen senses of smell, sight, touch, and taste. They have long whiskers on their face and in clumps on the top of their head. These help the devil locate prey when foraging in the dark, and aid in detecting when other devils are close during feeding. The whiskers can extend from the tip of the chin to the rear of the jaw and can cover the span of its shoulder. Hearing is the dominant senseL They can smell things that are one kilometer km (0.62 miles) away. Since devils hunt at night, their vision seems to be strongest in black and white. In these conditions they can detect moving objects readily, but have difficulty seeing stationary object. [Source: Wikipedia; Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Tasmanian devils communicate with a wide variety of vocalizations and physical cues. A study of feeding devils identified twenty physical postures, including their characteristic vicious yawn and raising their tails, and eleven different vocal sounds, including clicks, hisses shrieks and various types of growls that devils use to communicate as they feed. They are famous for their blood-curdling shrieks and growls that they make when a group feeds on a carcass together and are the source of their name.

Tasmanian devils usually establish dominance by sound and physical posturing, although fighting does occur. The white patches on devils are visible to the night-vision of other devils. Adult males are the most aggressive, and scarring — which includes torn flesh around the mouth and teeth, as well as punctures in the rump — is common and evidence of fights. They can also stand on their hind legs and push each other's shoulders with their front legs and heads, similar to sumo wrestling.

Tasmanian Devil Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Tasmanian devils are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners, and engage in seasonal breeding. They breed once a year, usually in March and April. The average gestation period is 21 days. The number of offspring ranges can be as many four, with the average number being two or three. [Source: Tanya Dewey; Bridget Fahey; Almaz Kinder, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|; Wikipedia] ]

Males compete for access to breeding females and females usually mate with dominant males. The mating unions of males and females are short-lived. Mating takes places in sheltered locations during both day and night. Males fight one another for females, and guard their partners to prevent female infidelity. Females can ovulate three times in as many weeks during the mating season, and 80 percent of two-year-old females are seen to be pregnant during the annual mating season.

Tasmanian devil young, variously called "pups", "joeys", or "imps". are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by females. Most mating takes place in March and the young are born in April. Females have four mammae are available and thus only four young are possible. After birth young then travel to the pouch where they remain for four months. At birth, newborn are pink, lack fur, have indistinct facial features, and weigh around 0.20 grams (0.0071 oz). The weaning age ranges from five to six months and the average time to independence is eight months. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age two years.

Female Tasmanian devil average four breeding seasons in their life, and give birth to 20 to 30 live young. Their pouch, like that of wombats, opens to the rear, making it physically difficult for females to interact with young inside the pouch. Young grow rapidly, and are ejected from the pouch when they weigh roughly 200 grams (7.1 oz). After being ejected, the devils, young remain in the den for around another three months, first venturing outside the den between October and December before becoming independent in January. During the transitional phase out of the pouch, young devils are relatively safe from predation as they are generally accompanied. When the mother is hunting they can stay inside a shelter or come along, often riding on their mother's back. During this time they continue to drink their mother's milk. Female devils are occupied with raising their young for all but approximately six weeks of the year. On average, more female young survive than males, and up to 60 percent of young do not survive to maturity. Juveniles are good at climbing trees, perhaps to evade males, which sometimes eat young.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025