Home | Category: Marsupials

MULGARAS

Mulagra (Dasycercus) are fierce rat-size, predatory marsupials that look like a cross between a mouse and a fox. Closely related to the Tasmanian devil and quolls, they feeds on insects and tiny marsupials. When they prey on the latter they kill them first with a bite to the neck and then consuming them from head to foot by pealing back the skin like the skin of a banana.

There are six species of mulgaras. Traditionally, two distinct but very similar species were recognized. 1) brush-tailed mulgaras (Dasycercus blythi, previously classified as Dasycercus cristicauda), has an uncrested tail, two upper premolars, and six nipples. 2) The crest-tailed mulgaras (previously Dasycercus hillieri, but now reclassified as Dasycercus cristicauda) has a crested tail, three upper premolars, and eight nipples. 3) More recently, tAmpurta (Dasycercus hillieri) were once again recognized as a separate species. Also, recently, three additional species have been described: 4) southern mulgaras (Dasycercus archeri), 5) the little mulgara (Dasycercus marlowi), and 6) northern mulgara (Dasycercus woolleyae). Black-crested mulgara are the about the size of a guinea pig. They weigh less than 150 grams (five-and-a-half ounces) and have pale, blond fur. Their thick tail, measuring a little less than half its body length, is tipped with a distinctive black crest that gives the animal its name. They have been described as "ferocious little micro predators" that eat small mammals, reptiles, and insects. [Source: Wikipedia, National Geographic]

Mulgaras inhabit arid, sandy regions of Australia in deserts and spinifex grasslands. Found mainly in the arid region from the Pilbara in northwestern Australia to southwestern Queensland, they live in burrows that they dig on the flats between low sand-dunes or on the slopes of high dunes. The complexity of the burrow varies. Burrows in central Australia usually have only one entrance with two or three side tunnels and numerous pop-holes, while those in Queensland have more than one entrance and deeper branching tunnels. [Source: Wojtek Nocon, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List five of the six species of mulgara are classified as species of “Least Concern”. Crest-tailed mulgara, previously referred to as Ampurta, are listed as vulnerable. Mulgaras ae considered threatened and vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) act in Australia. They are relatively common in Northern Territory and rare in Queensland and South Australia. It is believed that their numbers have declined significantly since the arrival of Europeans and the decline is mainly attributed to habitat loss, habitat disturbances and the introduction of livestock, rabbits, foxes and cats.

In 2017, scientists from the Wild Deserts conservation group spotted the first crest-tailed mulgara in Tibooburra's Sturt National Park, in far northwestern corner of New South Wales, bordering South Australia and Queensland, in more than a hundred years. National Geographic reported: Invasive rabbits, cats, and foxes brought to the area by European settlers centuries ago were thought to have driven the mulgara to local extinction. For a time, the marsupial was only known from fossilized bone fragments found in owl pellets in caves across the region. But recently, the mulgara has expanded its numbers across the border in South Australia's Strzelecki Desert, which lies about 285 kilometers (175 miles) north-west of Sturt National Park. A conservation project set up Sturt National Park set up a sanctuary with two fenced exoclosures to keep predators away for locally extinct mammals such as the greater bilby, burrowing bettong, Western quoll, and Western barred bandicoot. Crest-tailed mulgaras were also slated to be reintroduced to the area through the conservation program, but it appears the mammal has already weaseled its way back into the park. This may be because of a decline in the local rabbit population due to rabbit calicivirus, a widespread leporine hemorrhagic disease. [Source: Elaina Zachos, National Geographic, December 19, 2017]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DASYURIDS AND DASYUROMORPHS (MARSUPIAL CARNIVORES) ioa.factsanddetails.com

DUNNARTS: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PLANIGALES: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANTECHINUSES: SPECIES, FALSE ONES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUICIDAL MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN DEVILS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

TASMANIAN WOLVES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

NUMBATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

QUOLL SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

MARSUPIALS IN AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Mulgara Characteristics and Diet

Mulgaras on average weigh 115 grams (4 ounces). They have a head and body length of 12.5 to 20 centimeters (4.9 to 7.9 inches). Their tail is 7 to 13 centimeters (2.7 to 5.1 inches). Their average basal metabolic rate is 0.26 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. Mulgaras live up to at least six years in the wild. Mortality is probably highest among young mulgaras. [Source: Wojtek Nocon, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mulgaras are are compactly built, with short limbs, a broad head, short ears, and a pointed snout. The pouch area consists of two slightly-developed, lateral folds of skin. Mulgaras vary from buffy to bright reddish brown on the upper parts of their body. Their underparts are usually white or creamy. The fur is dense and soft, and consists primarily of underfur with few guard hairs. The tail is usually thicken for about two thirds of its length and near the body is densely covered with coarse, chestnut hairs. In the middle, the hairs are coarse and black, and they increase in length toward the tip to form a distinct dorsal crest. The pouch comprises two lateral folds of skin. The generic name Dasycercus means "hairy tail".

Mulgaras are recognized as carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and insectivores (eat insects and non-insect arthropods). Their diet includes insects, birds, mammals, reptiles and non-insect arthropods such as spiders, Mulgaras are able to consume 25 percent of their own weight in food and can subsist without drinking water or even eating succulent plants, because it is able to extract sufficient water from a diet of lean meat or mice. Their kidneys are highly developed to excrete extremely concentrated urine to preserve water.

Mulgaras attack mice, and mouse-size marsupials and other small vertebrates with lightening speed. It then devours the animal methodically from head to tail, inverting the skin in a remarkably neat fashion. They are also skillful at dislodging insects from crevices by means of its tiny forepaws.

Mulgara Behavior and Reproduction

Mulgaras are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They are mostly nocturnal, but occasionally "sunbathe" in the entrance of the burrow in which they live. [Source: Wojtek Nocon, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mulgaras are terrestrial, but they are capable of climbing. Most foraging is done at night. They avoid the heat during the hot part of the day by remaining in their burrows. When sunning themselves, the body is flattened against the ground, and the tail twitches sporadically. In captivity, mulgaras can be kept in pairs, and they generally do not fight with each other and tend to rather cordial with each other. The primary predators of mulgaras may be large snakes, dingoes, cats, foxes and humans. Mulgaras seek refuge from predators in their burrows and by being vigilant.

Mulgaras sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling and have keen vision, smell, touch, and acoustic senses. All species of mulgaras engage in daily torpor (decreased physiological activity usually marked by a reduced body temperature and metabolic rate). In contrast to most other mammals, mulgaras increase their use of torpor during pregnancy. By conserving energy with torpor, pregnant females can increase their body mass, but it seems they use it to increase fat storage, for lactation later. Pregnant females and breeding males both use torpor during the winter. Free-ranging males, however, only display torpor briefly during the reproductive season, and instead increase their use of torpor after the breeding season is over.

Little is known about mating in mulgaras. They are seasonal breeders and breed from June to September. . Gestation is approximately 30 days and the litter size is six to eight. Parental care is carried out by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. The young first detach from the nipples at about 55 days and are independent at four months. Individuals of both sexes have been known to come into breeding condition each year for six years. On average males and females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at ten and half months.

Dibblers

Dibblers (Parantechinus apicalis) are an endangered species of marsupial that inhabit the southwest mainland of Western Australia and some offshore islands and are sometimes called southern dibblers. A member of the order Dasyuromorphia, and the only member of the genus Parantechinus, they are small, nocturnal carnivore with speckled fur that is white around the eyes. [Source: Wikipedia]

Dibblers were once widespread throughout southwest Australia, but today they are found only in small populations on the mainland. Two larger populations have recently been found inhabiting Boullanger and Whitlock Islands in Jurien Bay in Western Australia. On Whitlock Island they prefer dense vegetation such as dunal scrubland and succulent heath. This may be due to the protection it provides from predators or an increased abundance of insect prey. When released from captivity into the wild they take refuge in seabird burrows. On Boullanger Island there seemed to be no preference of habitat as the entire island is fairly regular and has no trees. [Source: Megan Coughlin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, dibblers are classified as Endangered. In the early 19th century, dibblers were widely distributed across Western Australia. By 1884, they were declared extinct, but some were rediscovered at Cheyne Beach on the southern coast of Western Australia in 1967. Dibblers have been threatened by human development, habitat destruction (land clearing, dieback) and burning, and the introduction of foxes and cats. Dibblers are presently undergoing extensive conservation efforts, involving the Perth Zoo and the Department of Environment and Conservation, including successful translocations of captive-bred individuals to Escape Island. The initial success rate was high, with three generations surviving after the initial relocation.

Dibbler Characteristics and Diet

Dibblers are small marsupials. They are 10 to 16 centimeters (3.9 yo 6.3 inches) long with a 7.5–12-centimeters (3.0–4.7-inch) tail, and weighs 40 to 125 grams (1.4 to 4.4 ounces). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males average 14.5 centimeters (5.7 inches) in length and weigh 60 to 125 grams (to 4.4 ounces). Male dibblers found on the mainland are generally heavier than island individuals. Females are smaller and averge 14 centimeters (5.7 inches) in length and weigh 40 to 75 grams (1.4 to 2.6 ounces. [Source: Megan Coughlin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); Wikipedia]

Dibblers have pointed snouts, long whiskers, and strong jaws with sharp teeth. Grooves on the pads of their feet, which provide good traction, and sharp claws allow them to get a good grip on trees and rocks. Dibblers has rather coarse fur with a freckled appearance. The fur is brownish grey above and grayish white with yellow underneath. Distinctive features include white eye-rings are relatively large eyes, gray-brown fur flecked with white hairs, and a short tapering tail.

Dibblers are primarily insectivorous, eating whatever insects they can find and what is available in changing environmental and seasonal conditions, but are officially omnivores (animals that eat a variety of things, including plants and animals). Known prey includes grasshoppers, cockroaches, beetles, termites and ants (Hymenoptera). They are semi-arboreal and also feed on nectar from flowering plants, fruits and berries of Rhagodia baccata. Plant material makes up around 20 percent of their diet. Dibblers have strong jaws and large canine teeth for killing prey, which includes small vertebrates such as mice, birds and lizards, as well as insects and non-insect arthropods such as spiders. Dibblers show no significant differences in their diet during different seasons.

Dibbler Behavior

Dibblers are mostly solitary, terricolous (live on the ground), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). [Source: Megan Coughlin, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); Wikipedia]

Dibblers hunt for large insects at dawn and dusk. They are capable of jumping or climb trees or bushes to catch their prey. During the day they take shelter and rest in logs or between rocks. In reintroduced populations they form groups which vary around 100 individuals. On the mainland dibblers prey on insects and are often prey to larger mammals. On the islands dibblers face little danger of predation but compete with introduced house mice for food.

Dibblers communicate with vision, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals. Dibblers vocalize but not so much. Vocalizations are usually only heard during mating and plays no role in the attraction of mates.

The main known predators of dibblers are introduced red foxes and feral cats. The color of the fur of dibblers, which matches their environment, is their best camouflage. They are also able to move quickly and easily through dense vegetation and, for these reasons, have few natural predators. Mainland populations are heavily preyed upon by introduced red foxes and feral cats.

Dibbler Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Dibblers are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They engage in seasonal breeding, breeding once a year from March to April. The gestation period for dibblers of 44 to 53 days is long compared to other small dasyurids. The average number of offspring is eight. Young reach independence at three to four months On average males and females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 10 or 11 months.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Typical behaviors prior to and during mating include sniffing of the cloacal and facial regions and rump by both the male and female. This behavior is common and increases in intensity as the female approaches estrus. Chases and attempted mountings are frequent. The male may chase the female or vice versa. Often the animals vocalize when they are chasing or attempting mountings. Mountings are initiated by the male and there are many attempts that are unsuccessful. Chasing and unsuccessful mountings may occur up to 15 days prior to copulation. Successful mountings involve the male clasping the female in a neck-grip and a single copulation may continue for a few hours.

In captivity and in the wild dibblers individuals live two to three years. On Boullanger Island males display semelparity where they die immediately after the breeding season, but on the mainland. Extremely high energy demands during the breeding season, elevated levels of free corticosteroids in the blood, and related disease such as ulcers, anemia, and parasite infestation ultimately cause the death of males. Because mainland males survive for multiple breeding seasons, this male die-off could be environmentally determined. One possible explanation is the effect of nesting seabirds including bridled terns and white-faced storm petrels on resources. Seabirds affect nutrients in the soil; post-breeding survival is significantly higher on Whitlock Island which has many seabirds, 18 times more nutrients in the soil and a larger amount of insects.

Females are only able to breed once annually, but males may are able to breed in multiple times in a year. Parental care is carried out by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. After a female gives birth she may carry up to eight young in her shallow pouch. She provides food and protection until the young reach independence and disperse in September and October.

Kultarrs

Kultarrs (Antechinomys laniger) are also known as jerboa-marsupials, marsupial jerboas, Jerboa marsupial mice, wuhl-wuhl, and pitchi-pitchi. They are small nocturnal marsupials that feed mainly on insects and inhabit the arid interior of Australia. Kultarrs have a range of adaptations that help them cope with their harsh, arid environment including the ability to extract water from their food. Jerboas are hopping desert rodents found throughout North Africa and Asia. The word "kultarr" originates from the Yitha Yitha Aboriginal language.

Kultarrs are one of the rarest and most elusive Dasyuridae (marsupial carnivores), which themselves are elusive. According to The Conversation: Kultarrs are feisty insect-eater found in very low numbers across much of the outback. To the untrained eye, the kultarr looks very much like a hopping mouse, with long legs, a long tail and a tendency to rest on its hind legs. However, it runs much like a greyhound — but its tiny size and high speed makes it look like it’s hopping.” [Source: The Conversation, June 30, 2025]

Kultarrs are found in arid to semi-arid plains, stony deserts, shrublands, and grasslands in Northern Australia, Western Australia, and New South Wales. There are two regional subspecies: 1) Antechinomys laniger laniger in the the eastern part their range; and 2) Antechinomys laniger spenceri in the central and western parts of this range. Kultarrs prefer heavy soils including stoney, sandy, or clay filled soils. During the day, they seek cover in stumps, spinifex tussocks, cracks in the soil, and burrows of other animals. Antechinomys laniger laniger prefers claypans in Acacia woodlands, while Antechinomys laniger spenceri prefers plains of granite and shrub lands. [Source: Everett Beck, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kultarrs are generally not considered endangered or threatened. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). On the U.S. Federal List they are classified as Endangered. Kultarr are widespread, and populations are believed to fluctuate with rain levels but the species has declined across its former range since European settlement. Over-grazing by cattle and sheep, fires and predation by feral cats and red foxes are major threats. Localized extinctions have occurred in New South Wales and South Australia.

Kultarr Characteristics and Behavior

Kultarrs are small and mouse-like in appearance. They range in weight from 20 to 30 grams (0.7 to 1.1 ounces) and are 17 to 20 centimeters (6.7 to 7.9 inches) long, including their tail. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are about 1.5 centimeters longer and 10 grams heavier than females. The fur of kultarrs is grey to sandy brown, and the long tail has brush-like dark hairs on the sides. The dark coloring around the eyes, mid-line, and top of the head varies among individuals. As they are primarily active at night, they have large round eyes and large ears. They have elongated hind feet with four independent digits that help them hop. Kultarrs are relatively long lived mammals for their size — living up to 5.6 years in the wild. [Source: Everett Beck, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Kultarrs are solitary, terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing) and have daily torpor (a period of reduced activity, sometimes accompanied by a reduction in the metabolic rate, especially among animals with highmetabolic rates). Kultarrs are rarely observed by humans because of their solitary and nocturnal behavior. Their behavior is temperature dependent. At times of cooler temperatures, kultarrs are more active and enter torpor earlier in the night.

Kultarrs are insectivores (eat insects and other arthropods) and feed mostly on spiders, cockroaches, and crickets. Their agility and speed and resistance to poisons allows them to catch quick and venomous prey. Kultarrs move with a bounding gait, alternating using their lengthened hind feet and their smaller front paws. They have been recorded moving at 13.8 kilomters per hour. Their hopping-style motion provides high maneuverability, which may aid in catching quick or dangerous prey and avoiding predators. |=|

Kultarrs communicate with sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Their abnormally large eyes and ears are adapttion to their nocturnal lifestyle. Primary predators of kultarrs include feral cats and red foxes. Their nocturnal lifestyle and agility help them to avoid many predators. During the day, kultarrs stay in the nest to avoid diurnal (active during the daytime) predators.

Kultarr Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Kultarrs engage in seasonal breeding and may breed more than once each breeding season. The breeding season is from midwinter to midsummer (July to February). The gestation period ranges from 12 to 17 days. The number of offspring ranges from one to eight, with the average number of offspring being six. [Source: Everett Beck, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Little is known about mating systems of kultarrs. It is suspected that olfactory cues are used in mate selection. Females are polyoestrous and may enter estrus up to six times during the breeding season. Estrus cycles occur from July to January and may be dependent on seasonal amounts of daylight. Breeding females have a supple pouch, elongated nipples, and long red-brown hairs. Males begin spermatorrheoea in May. After the breeding season, the female's pouch regresses into a small fold.

Parental care is provided by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. After birth, the young crawl into the pouch, where they remain for 30 to 48 days. Parents and offspring communicate vocally. Young use calls to locate their parents when they become separated. Weening occurs at 80 to 90 days of age in captivity. After they are weaned, young remain in the nest as the mother forages. When older, they ride on their mother's back as she searches for food. Males and females reach sexual maturity at 11.5 months of age.

Turns Out Kultarrs Are Three Different Species

In June 2025, scientists announced that what had been thought was a single kultarr species was actually three species, based on genetic study in 2023 and research by scientists from the University of Western Australia, Western Australian Museum and Queensland University of Technology. These scientists wrote in The Conversation: We travelled to museums in Adelaide, Brisbane, Darwin, Melbourne, Sydney and Perth to look at every kultarr that had been collected by scientists over the past century. By combining detailed genetic data with body and skull measurements, we discovered the kultarr isn’t one widespread species, but three distinct species. [Source: Cameron Dodd, PhD Student in Evolutionary Biology and Taxonomy, The University of Western Australia; Andrew M. Baker, Associate Professor in Ecology and Environmental Science, Queensland University of Technology; Kenny Travouillon, Curator of Mammals, Western Australian Museum; Linette Umbrello, Research associate, Western Australian Museum; Renee Catullo, Senior Lecturer, School of Biological Sciences , The University of Western Australia,The Conversation, June 30, 2025]

The Three species of kultarrs are:

Eastern kultarrs (A. laniger) is the smallest of the three, with an average body length of about 7.5 centimeters. It’s darker in colour than its relatives, and while its ears are still big, they are nowhere near as big as those of the other two species. The eastern kultarr is now found on hard clay soils around Cobar in central NSW and north to around Charleville in southern Queensland.

Gibber kultarrs (A. spenceri) is the largest and stockiest, with an average body length of around 9 centimeters. They are noticeably chunkier than the other two more dainty species, with big heads, thick legs and much longer hindfeet. As its name suggests, the gibber kultarr is restricted to the extensive stony deserts or “gibber plains” in southwest Queensland and northeast South Australia.

Long-eared kultarr (A. auritus) is the middle child in terms of body size, but its ears set it apart. They’re nearly as long as its head. It’s found in patchy populations in the central and western sandy deserts, living on isolated stony plains.

All three species of kultarr are hard to find, making it difficult to confidently estimate population sizes and evaluate extinction risk. The long-eared and gibber kultarrs don’t appear to be in immediate danger, but land clearing and invasive predators such as cats and foxes have likely affected their numbers. The eastern kultarr, however, is more of a concern. By looking at museum specimens going back all the way to the 1890s, we found it was once much more widespread.

Historic records suggest the eastern kultarr used to occur across the entirety of arid NSW and even spread north through central Queensland and into the Northern Territory. We now think this species may be extinct in the Northern Territory and parts of northwest Queensland.

Ningaui

Ningaui are tiny marsupial carnivores that belong to the Dasyuridae family and look a bit like shrews. Along with the planigales, they are among the smallest marsupials. The name "ningaui" refers to a creature from Aboriginal myth. Mike Archer, who first described ningaui, read an Aboriginal story about these tiny minute hairy creatures that emerged at night and ate food uncooked and thought that ningaui would be an apt name for the new genus.

There are three species in Ningaui genus: Wongai ningaui (Ningaui ridei), Pilbara ningaui (Ningaui timealeyi) and Southern ningaui (Ningaui yvonneae). Southern ningaui were first described in 1983, and placed within the genus Ningaui, which was not established until 1975, when Wongai ningaui and Pilbara ningaui were first described and compared with Sminthopsis (the dunnarts). Southern ningaui look very similar to Wongai ningaui. [Source: Wikipedia]

Southern ningaui found in southern, central Australia mainly in spinifex on semi-arid sandplains inland from the southern coast of Victoria, South Australia and southern Western Australia. Southern ningaui occupy a range of semiarid habitats, including open heathlands and low mallee scrub of Victoria and South Australia as well as the sandy plains of Western Australia. Mallee trunk, shrub roots, leaf litter, woody debris, and bare ground are important habitat components. [There is a commensal relationship between southern ningaui and Triodia, a genus of hummock-forming grass endemic to Australia. Triodia provide southern ningaui with both food and protection. The leaves are home to insect prey and provide an ideal foraging habitat. The leaves are pointed and sharp, making it a useful anti-predator defense. Southern ningaui seek habitats with high densities of this grass. Source: Francesca Stephenson, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Ningaui are not endangered or threatened.They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). They generally reside in harsh environments not affected much by humans. Southern ningaui inhabit some protected areas, including several in western Australia. Currently, there are no major threats to the populations of Southern ningaui, although localized habitat fragmentation is occurring due to mining, sheep grazing, and inappropriate fire regimes. Scientists have noted that southern ningaui are not affected much by the presence of humans and would even forage at the researchers’ feet.

Southern Ningaui Characteristics and Diet

Southern ningaui are very small. They range in weight from 10 to 12 grams (0.35 to 0.42 ounces) and have a head and body length of 4.6 to 5.7 centimeters (1.8 to 2.2 inches). Their average basal metabolic rate is 2.1 cubic centimeters of oxygen per gram per hour. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. Their lifespan in the wild is typically 12 to 14 months.[Source: Francesca Stephenson, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Southern ningaui fur is uniformly short and tawny or greyish olive colour, light grey below, and distinguished by shades of cinnamon. The tail is long, thin and hairless and is roughly the same length as the body. The head is large relative to the body, and has a conical snout with short, thin whiskers. The ears are short and oval. The eyes are round, medium-sized, and black. The manus and pes are small and delicate with thin, long digits. Southern ningaui cannot be distinguished from other species in the genus Ningaui by external features alone, making identification difficult in field work. Scientists have had to use allozyme electrophoresis on blood samples to distinguish Southern ningaui from Wongai ningaui. |=|

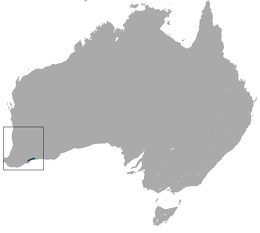

range of three Ningaui species: Pilbara ningaui (left); Southern ningaui (middle) and Wongai ningaui (right)

Southern ningaui are recognize as carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and insectivores (eat insects and non-insect arthropods). They primarily eat insects although they have been known to eat occasional vertebrate prey, such as reptiles. They are less generalist in diet than most dasyurids. They do not prefer ants, although ants are abundant in Triodia grasslands. Southern ningaui feed on spiders, beetles, moths, roaches, and other arthropods. Southern ningaui prefer smaller prey, including insects and spiders, but is capable of killing and consuming larger animals such as cockroaches and skinks. Their narrow muzzle is used with quick and fierce bites about the head to despatch their meal. They also forage by “furrowing,” placing the snout in the soil or leaf litter and moving. They occasionally enter spider burrows to eat the inhabitants.

Southern Ningaui Behavior and Reproduction

Southern ningaui are terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and sedentary (remain in the same area).Little is known about their behavior. Only one population has been studied in detail: Bos et al. (2002) studied the population of the Middleback Ranges on the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia, They can run fast are solitary, except during breeding and raising of young. During the day they rest in underground burrows. At night they forage in leaf litter and mallee stem above ground. Southern ningaui communicate with sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Mating vocalizations are the only forms of interspecific communication that has been observed. Although primarily terrestrial, they have been observed climbing vegetation for brief periods. Southern ningaui move slowly by walking. When fleeing predators they run with a quadrupedal, bounding gait. They have also been observed licking their fur and using their forepaws to groom or perhaps cool themselves. [Source: Francesca Stephenson, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Snakes are the main predators of southern ningaui, particularly those in the family Elapidae, which are often venomous. Southern ningaui many escape predators by fleeing along trails, but they prefer to hide, either in burrows or mallee stems. Predator activity, and consequently predator avoidance behavior according to season. The risk of predation is greatest when southern ningaui are found in open habitats such as leaf litter, so they tend to avoid these habitats and seek cover in shrubs and spiny grasses during the warm season, when snake predation is at the greatest risk. Burrows can be used during winter months, when predator risk is lower and keeping warm is a greater priority.

Southern ningaui appear to be polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They engage in seasonal breeding — breeding once per year during the spring from August to October. Females are polyestrus (females have multiple estrous cycles, periods of sexual receptivity, per year). Polyestrus cycles in Southern ningaui apparently function to replace lost litters, rather than to allow more than one litter per season. The number of offspring ranges from five to seven. [Source: Francesca Stephenson, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Males defend a female in estrus during her receptive period. Males in captivity are intolerant of one another outside of breeding season. Both sexes produce mate-attracting calls. Males use soft clicks or hisses to attract females and females respond with calls during receptive periods. Males define territories in which they search for mates by marking surfaces, such as bark, with sternal glands. Behavioral estrus can last for one to three days. The maximum length of copulation is 4.5 to five hours. Sperm can be stored for two to three days and sperm competition is unlikely.

Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by females, who nurtures the young in their pouch. While raising young, females seek protection from predators in shrubs and spiny grasses. Females with young in their pouch have more difficulty fleeing rapidly. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at six to 11 months, with the average being eight months. Most adults die by the fall season beginning in February. At this time, dispersing juveniles comprise about 97 percent of the population.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2025