Home | Category: Island Ethnic Groups

MASSIM AND MILNE BAY PROVINCE

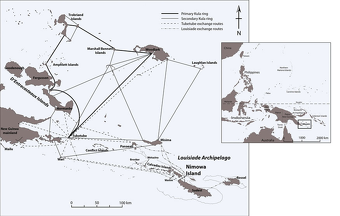

"Massim" is a region and cultural area in southeastern Papua New Guinea known for the Kula ring, an inter-island exchange of ceremonial valuables, and its distinctive traditional art. It includes the southeastern tip of mainland New Guinea and its offshore islands, including the Louisiade Archipelago and Trobriand Islands. The Kula ring system involved the exchange of shell necklaces and armbands between islands to build social and political relationships. Among the region’s renowned artworks are intricate carvings on objects such as canoe prows, drums, and lime spatulas, often decorated with black, white, and red paint.

Massim lies in Milne Bay Province which covers 14,345 square kilometers (5,540 square miles) of land and 252,990 square kilometers (97,680 square miles) of sea, encompassing more than 600 islands, about 160 of which are inhabited. The capital is in Alotau. Around 276,000 people live in the province, speaking roughly 48 languages, mainly of the Eastern Malayo-Polynesian branch. Tourism, oil palm, and the former Misima gold mine are key economic activities, alongside small-scale cocoa and copra production. The province was the site of the World War II Battle of Milne Bay.

Culturally, Massim is also noted for matrilineal cultures and extended mortuary ceremonies, with practices varying markedly from island to island. Milne Bay’s coral reefs are among the world’s most diverse. The D’Entrecasteaux Islands retain volcanic activity, especially near Dobu and Fergusson. Some island groups, such as the Amphletts and Trobriands, remain lightly charted and seldom visited, while the Louisiades are a common stop for international yachts. Although the Misima mine closed in 2001 (with milling into 2004), exploration continues on Woodlark and Normanby Islands.

Vanatinai is an island located in the Louisiade Archipelago also known as Tagula Island or Sudest Island. On the sex life of the islanders there, anthropologist Maria Lepowsky (1990) wrote: “Sexual activity on Vanatinai is regarded as a pleasurable activity appropriate for men and women from adolescence to old age…Young people vary in the age at which they become sexually active, but it is usually in the mid-teens. Parents may tell they daughters that they are “too young” to have sex, as did the mother of one fifteen-year-old when she began to be courted by a young man whom the mother disapproved...On the other hand, some parents feel concerned if their daughters are not receiving lovers by the time they are in their late teens”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ISLANDERS OF NORTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA ON MANAM, WOGEO AND MANUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, BIG MEN POLITICS, ECONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDER CULTURE: CUSTOMS, MATRILINEAL SOCIETY, SEX AND YAMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE TROBRIAND ISLANDS AND MASSIM REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

EAST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — THE BAINING AND TOLAI — AND THEIR CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES AND DANCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WEST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — NAKANAI, AROWE — AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MASKS AND ART OF NEW BRITAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

NEW IRELAND ETHNIC GROUPS — MADAK, LESU, AND LAK— AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM NEW IRELAND: MALAGAN, FUNERARY FIGURES AND DRUMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOUGAINVILLE ISLANDERS — SIWAI, TINPUTZ, NAGOVISI — AND THEIR HISTORY, SOCIETIES AND CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NASIOI OF BOUGAINVILLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

NISSAN ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Kula Exchange System

The Kula is a ceremonial gift-exchange network practiced by the Trobriand Islanders and neighboring Massim groups of Milne Bay. It centers on the lifelong, reciprocal circulation of two prestige valuables: red shell-disc necklaces (soulava), which travel clockwise, and white shell armbands (mwali), which move counterclockwise. These items are not utilitarian commodities; they are temporarily held to gain honor before being passed on.

How It Works:

1) Opposite Directions: Soulava circulate clockwise around the Kula ring, while mwali circulate counterclockwise.

2) Ceremonial Gifting: Exchanges are not barter; partners give and receive valuables as part of a ritual cycle that emphasizes generosity.

3) Lifelong Partnerships: Each exchange creates enduring partnerships involving obligations of hospitality, assistance, and protection.

4) Prestige Through History: The value of each item lies in its provenance—who has owned it, where it has traveled, and how long it was held.

5) Continuous Movement: Valuables are always in motion, completing long circuits that may take years.

Cultural Significance:

1) Strengthening Bonds: Kula maintains alliances and peaceful relations among far-flung islands.

2) Prestige and Social Rank: Influential participants handle more renowned items and thus gain greater status.

3) Non-Commodity Gifts: Kula valuables function as vehicles of social capital, not as objects for sale or ordinary trade.

Trobriand Islanders

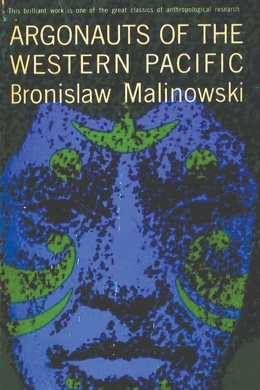

The Trobriand Islanders are the residents of the Trobriand Islands, a small group of coral islands about 200 kilometers (125 miles) north of the eastern tip of New Guinea. These islanders were the subjects of Bronislaw Malinowski’s "The Sexual Life of Savages in Northwestern Melanesia", a famous anthropological work published in 1927. Old-timers that remembered Malinowski in the 1990s called him the “man who asked questions”. In his studies Malinowski reported that the Trobriand Islanders were "keen on fighting" and they often fought "systematic and relentless wars" as well as engaging in unusual sexual practices.

The Trobriand Islander traversed large expanse of open ocean in canoes to trade and fight. They often traveled great distances over open ocean to trade shells in something called the kula game. The shells which look worthless to westerners are given from one group of islanders to another, who in turn pass them on to other islanders. The islanders in this region have been doing this for hundreds of years and the their shells are as valuable to them as four foot yam, which are greatly treasured. Author Paul Theroux asked one islander how he navigated the open ocean,"We can smell the islands," he replied.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROBRIAND ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, BIG MEN POLITICS, ECONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDER CULTURE: CUSTOMS, MATRILINEAL SOCIETY, SEX AND YAMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE TROBRIAND ISLANDS AND MASSIM REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Dobuans and Dobu Island

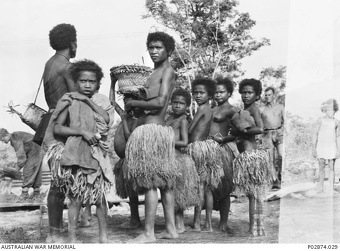

Family on Dobu Island Colin Munro Photography

Dobu is a small island measuring 3.2 by 4.8 kilometers (two by three miles) dominated by an extinct volcano. Known as Goulvain Island in the past, Dobu is also the name of the language of its inhabitants and, more generally, of those speakers of the same language on neighboring areas — on southeastern Fergusson, northern Normanby, and the offshore islands of Sanaroa and Tewara. The anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski described Dobuans as single tribe — implying a unified linguistic, cultural, and political unit— but this broader notion was largely a creation of early missionaries and anthropologists. Today they are referred to as Dobuans or Dobu islanders. Dobuans refer to themselves as Edugaura. [Source: Michael W. Young, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Dobu lies in Dawson Strait (9.45° S, 150.50° E), between Fergusson and Normanby in the D’Entrecasteaux Archipelago of Milne Bay Province. Natural vegetation on Dibu and nearby island is lowland rainforest, though many settled areas are now covered with secondary forest or grassland. The climate is tropical, with southeasterly winds from May to November and the northwest monsoon from December to April, which brings heavy squalls. Annual rainfall averages about 254 centimeters (100 inches), but periodic droughts occur.

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Dobu, Galuewa population in the 2020s was 22,000. The 1980 census counted about 10,000 Dobu speakers. Dobu Island itself had about 900 residents in the 1990s, though missionary William Bromilow estimated 2,000 inhabitants in 1891. Tiny Tewara Island had only 40 people when Reo Fortune worked there in 1928. At that time, Dobuan populations—like many in the Massim—had dropped to roughly half their former size.

Language: Dobu (or Dobuan) is an Austronesian language of Milne Bay Province and serves as a lingua franca for as many as 100,000 people in the D’Entrecasteaux Islands. It encompasses several local dialects and belongs to the Milne Bay branch of the Massim languages, with its closest relatives located elsewhere in the archipelago. The Edugaura dialect of Dobu Island was adopted by the Wesleyan Mission and subsequently spread throughout the central Massim and beyond.

History: In the late nineteenth century, Dobuans—especially the Edugaurans—were reputed as formidable warriors and feared cannibals, conducting local raiding alongside trade with Fergusson, the Amphletts, the Trobriands, Duau (Normanby), and Tubetube. External contact began in the mid-1800s with brief visits from whalers and pearlers, followed in 1884 by blackbirders who seized or killed men for labor recruitment. Dobu was visited in 1888 by Administrator Sir William MacGregor during his first tour of the newly declared British New Guinea, and in 1890 by Methodist leader Rev. George Brown, who was searching for a mission base. By then, copra traders were already present, steel tools and trade tobacco were circulating, and introduced diseases were reducing local populations.

The decisive turning point came on June 13, 1891, when missionary William Bromilow arrived with a party of sixty-three, including thirty Polynesian evangelists. Bromilow soon claimed to have pacified the district, though full Christianization of the Dobu-speaking region took more than four decades. According to Fortune, Dobu was a society permeated by jealousy and suspicion. At its troubled heart were the concepts of susu solidarity, marital antagonism, bilocal residence, and an all-pervasive fear of witchcraft and sorcery. Warfare was endemic in the nineteenth century, and the locality was the war-making unit. Furtive raids rather than pitched battles were the norm. Intermarriage between enemies was rare, though captives were sometimes adopted.

Dobuan Religion and Culture

Since the arrival of Methodist missionaries in 1891, the Dobu region has become thoroughly Christianized. Village churches—led by local lay preachers—are now central to community life. The Christian-group Joshua Project estimates that about 99 percent of Dobuans identify as Christian, with 10–50 percent considered Evangelical. Sundays and major Christian holidays are observed, and important mission anniversaries—especially the date of William Bromilow’s arrival—are commemorated with church offerings. Many Dobuans have become ministers and now serve congregations throughout the Massim. [Source: Michael W. Young, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Despite widespread Christian conversion, traditional beliefs in magic, witchcraft, and sorcery remain deeply embedded in everyday life. Yam cultivation continues to be guided by rituals, taboos, and magical formulas, and yams are still regarded as “persons” who may abandon a gardener who treats them improperly. Every woman is thought to be a potential witch (werebana) and every man a potential sorcerer (barau), with their spirit activities believed to be most powerful during sleep.

A complex pantheon of immortal spirit beings validates magical practices and explains the Dobu universe of “contending magical forces.” Key figures include Kasabwaibwaileta (hero of kune or kula), Tauhau (creator of the White man, his goods, and his epidemic diseases), Yarata (the northwest wind), and Bunelala (the first woman to plant yams). Others, like Nuakiekepaki—the moving rock-man who sinks canoes—are more abstract. Many spirits have secret names, invoked in incantations to harness their powers. Yabowaine, associated with war, cannibalism, and kune, was believed to shape the fingers and toes of unborn children; missionaries appropriated his name for “God,” vastly expanding his traditional significance. The most significant ceremonies involve periodic exchanges and feasts marking marriage and death.

Religious Practitioners and Healing: While some individuals are recognized as ritual experts or skilled diviners, most adults possess and use inherited magical knowledge. Magic related to gardening, romantic attraction, and kune is highly competitive and closely tied to social prestige. As Reo Fortune observed, “the ladder of social ambition is that of successful magic,” and access to potent magic often parallels wealth and political influence. Illness is almost always attributed to sorcery, witchcraft, or the violation of a taboo; healing typically involves resolving underlying social grievances. Ginger is the most common protective and curative substance, and many other plants are used, though their pharmacological value is doubtful.

Death initiates another cycle of affinal exchanges. The village of the surviving spouse presents yams, arm shells, and a pig—formerly a human captive—to the village of the deceased, who is buried by members of their susu (matrilineage). A year later, the susu releases the widow or widower from mourning, after which the spouse may never again enter the deceased’s village. Large memorial feasts (sagali) honor the collective dead, with pigs and yams distributed to surrounding communities. The spirits of the dead travel to Bwebweso, an extinct volcano on Normanby Island (“Bwebweso” meaning “extinguished”). Its entrance is guarded by Sinebomatu (Woman of the Northeast Wind), who demands betel nuts as payment from new arrivals. The diseased and deformed are believed to go to a swamp at the base of the mountain, while those killed in war have a separate afterworld.

Mythology and Arts: Dobu mythology is rich in narratives that legitimize magical practices. Decorative art, in the elegant curvilinear Massim style, traditionally adorned houses and canoes. Bamboo flutes and Jew’s harps featured in courtship, and feasting was accompanied by dance to hand drums. Many of the dance songs recorded by Fortune are noted for their emotional and poetic depth.

Dobuan Society and Kinship

The core of Dobu social structure is the three-generation matrilineage, or susu (“breast milk”). Matrilineages are the tracing of descent through the maternal line, meaning a person's ancestry and kinship are passed down through their mother's family Each susu traces descent through women to one of several mythical bird ancestors, most commonly the Green Parrot, White Pigeon, Sea Eagle, or Crow. All susu within a village are considered part of a single matriclan, descended from the same totemic bird. Across the broader Dobu-speaking region, these matriclans are widely dispersed and not grouped in any systematic pattern. Rights to garden and village land are based on matrilineal descent. A man inherits land from his mother or maternal uncle. A father may give his son some garden land—but never village land—although after the father’s death the son is forbidden to eat produce from that plot. In recent years, fathers increasingly pass land with cash crops, particularly coconuts, to their sons.[Source: Michael W. Young, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The village (asa)—composed of four to a dozen susu (matrilineages)—is the central social unit for arranging marriages and conducting mortuary exchanges. Between four and twenty villages form a named locality, which traditionally had a headman, typically a man who had inherited substantial magical knowledge and was influential in kune activities. Localities within a district (such as those on Dobu Island) were generally hostile to one another, though they occasionally united for warfare or kune expeditions under the leadership of a powerful “war chief and standard bearer.” One such leader was Bromilow’s associate Guganumore, credited with capturing eighty-six people; in 1892 he was formally appointed a government chief, further solidifying his authority.

Kinship Terminology: Dobuans use Iroquois-type cousin terminology while a father is alive. After a father’s death, however, the system shifts to Crow-type terminology, because a man’s sister’s son inherits the deceased man’s kinship status. In this transition, a dead man’s son refers to his father’s sister’s son as “father.” Under an Iroquois system (also known as bifurcate merging), parental siblings of the same sex as one’s parent are referred to by the same terms as “mother” or “father.” Opposite-sex parental siblings receive distinct terms equivalent to “aunt” and “uncle.” Their children—cross cousins—are classified separately and never as siblings, whereas parallel cousins (children of parental same-sex siblings) are addressed with sibling terms.

Political Organization: Dobu society is fundamentally egalitarian and does not feature the hereditary ranking systems found in the nearby Trobriand Islands. Administrative change began in 1961 with the establishment of the Dobu Local Government Council, and today the region elects a representative to the provincial government. Several Dobuans have also run for national parliament, often leveraging their kune networks as effective political support systems.

Before colonial administration and formal courts, Dobuans relied on self-help to resolve disputes. Sanctions could be social (shame, ridicule, public admonishment), supernatural (witchcraft and sorcery), or retaliatory (revenge killing, sorcery feuds, attempted suicide). The threat of sorcery was particularly effective in enforcing economic responsibilities. Village headmen frequently delivered public speeches to shame offenders. Theft—especially of fruit trees—was discouraged through charms (tabu) believed to cause disease or disfigurement. Many of these traditional sanctions persist today, though moderated by Christian values. Modern Dobuans also have access to a magistrate’s court, and local government councillors commonly mediate conflicts within villages.

Dobuan Family and Marriage

Dobuan households typically consist of a married couple and their young children. Adolescent girls remain at home until marriage, but boys leave at puberty to sleep elsewhere, usually with girls from nearby villages. After a man dies, his children are forbidden to enter his village. Land, fruit trees, and most garden plots are inherited matrilineally through the susu (matrilineal clan). The corpse, skull, and personal names of the deceased also belong to the susu, as do canoes, fishing nets, stone blades, ornamental valuables, and most other personal property. Magic, however, may be passed from a father to a son as well as to his matrilineal heir—something Fortune viewed as “subversive” of the susu system. [Source: Michael W. Young, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Childrearing is shared by both parents, who are generally strict. Children can avoid harsh discipline by seeking refuge with their mother’s sister and her husband, who are indulgent. Between ages five and eight, boys have their earlobes and nasal septum pierced by their father or maternal uncle, and they receive a small garden plot and sometimes snippets of magical knowledge. By age ten they are no longer physically punished, lest they imitate adult destructive behavior. Boys of this age practice spear-throwing and dodging, and by fourteen they begin learning love magic and sleeping with girls. Among the Dobuans, where girls become sexually active well before puberty, there are no formal initiation rites and no cultural fear of menstruation; adolescence passes with little ceremony. Fortune notes the obscenities of young boys but writes little about the socialization of girls.

Marriage is prohibited within a village’s owning susu and between cross cousins, making villages exogamous even though people tend to marry within the local region. Premarital sex is permitted, and adolescent promiscuity is common, despite Fortune’s description of the Dobuans as prudish in speech and public behavior. Betrothed couples work for a year for their future in-laws, and marriage is marked by a sequence of food exchanges between the two villages and the presentation of arm shells from the groom’s group to the bride’s. These exchanges continue annually on behalf of each married couple and ideally balance over time. Monogamy is the norm; only a few wealthy men (esa’esa) practice polygyny.

Dobu is especially known for bilocal residence, in which spouses alternate residence annually between each partner’s village. While affines show respect to village owners, tensions between the owning susu and incoming spouses can produce quarrels, accusations of village “incest,” and even attempted suicide. Fortune saw bilocal residence as a compromise between the demands of the susu and the conjugal unit, though one that weakened the latter. Divorce is common; Bromilow listed twenty-two causes—including “filthy language”—but Fortune regarded the most frequent as “cut-and-run adultery” with a village “sister” or “brother.” Affines are also feared as potential witches or sorcerers. In a later revision, Fortune suggested that bilocal residence is linked to the annual exchange of yams for arm shells between resident susu wives and their nonresident husbands’ sisters.

Dobu Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Swidden agriculture is considered the “supreme occupation,” and yam cultivation dominates the Dobu agricultural calendar. Individuals who lack their own yam strains are regarded as “beggars” and face difficulty finding marriage partners. Other traditional crops include bananas, taro, sago, and sugarcane, while sweet potatoes, manioc, pumpkins, maize, and several additional plants were introduced more recently. Fishing is an important supplement to gardening, and in forested regions men hunt wild pigs, birds, cuscus, and other small game. Pigs, dogs, and chickens are raised for domestic consumption and for use in exchange. Since early mission days, Dobuans have produced copra for cash, but during the colonial era migrant labor on plantations and in gold mines became the primary source of income and an essential rite of passage for young men. Today, Dobuans living away from home work in a wide range of occupations—clerks, civil servants, businesspeople, physicians, and lawyers—while the rural population continues to rely on subsistence gardening with some cash cropping, mainly copra and cocoa. The region is served by several wharfs and two small airstrips. [Source: Michael W. Young, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The “district” of Dobu Island traditionally consisted of about twelve “localities,” each made up of several small, dispersed villages averaging roughly twenty-five people. A typical village forms a circle of houses facing inward toward a central stone-covered grave mound where matriclan members are buried. Paths run around rather than through the settlement, which is surrounded by coconut, betel nut, and other fruit trees. Houses are rectangular structures raised on piles, with steeply pitched sago-thatch roofs, sago-thatch walls, and a small front verandah.

The most significant specializations were magical, with major economic implications: specialists controlled rain, crop and pig growth, fish abundance, and the curing of disease. Husbands and wives work together in their gardens, though each spouse maintains separate plots tied to their inherited seed yams. Gardens are cleared and planted communally, but once the village magicians have performed their rituals, they become the private domains of individual couples. Men and women clear the bush together, with men cutting heavier timber. Men burn debris and use digging sticks; women plant and cover the yam sets. Women weed and mound the plants, while men cut stakes and train the vines. Women dig most of the harvest; men plant and care for banana patches. Both sexes fish and make sago, and men handle cooking for ceremonial occasions. Traditionally, only men traveled on kune expeditions, though only elderly women were believed to possess the magic necessary to control the winds.

Traditional technology was neolithic and characteristic of Melanesia. Obsidian and stone adze blades were imported, but most other tools and weapons—bamboo knives, black-palm spears, wooden fishhooks, digging sticks—were made locally, as were the large seagoing canoes used in trading and raiding. Clay pots came from the Amphletts (and more recently Tubetube), while each household produced its own coconut-leaf baskets, pandanus mats, and skirts. Craft specialization was limited, mainly to canoe carving, net making, and the manufacture of arm shells. Magical expertise, however, remained the most valued specialization.

Trade: The ceremonial kula exchange (kune in Dobu), for which the Massim region is well known, continues today with significant modifications. Dobu remains a key hub within this interisland network through which arm shells (mwali) circulate southward and shell necklaces (bagi) circulate northward. Most kuna/kune voyages are now conducted by chartered motor launches rather than by canoe, simplifying the process, reducing ritual requirements, and allowing women to participate. Utilitarian trade is now minimal, though traditionally kune included not only shell valuables but also stone blades, obsidian, pottery, wooden bowls, pigs, sago, yams, betel nuts, face paint, lime gourds and spatulas, canoe hulls, and even human captives. Captives could be ransomed with shell valuables or adopted to replace dead kin. Kune was therefore closely connected with warfare, marriage exchanges, and mortuary rites.

Rossel Islanders

The Rossel Islanders are an indigenous group that live on Rossel Island, the easternmost island of the Louisiade Archipelago in Papua New Guinea's Milne Bay Province. Also referred to as the Duba, Rova and Yela, they are known for speaking the unique, non-Austronesian language Yelatnye and for their traditional social and economic practices, which include a complex system of ranked exchange using shell valuables and a high-quality red-shell necklace industry. [Source: John Liep, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Google AI]

Located approximately 370 kilometers (227 miles) southeast of the main island of New Guinea at about 11 ° S and 154° E, Rossel Island is located island is 34 kilometers (21.6) long and 14 kilometers (8.4 miles) across, and approximately 290 square kilometers (112 square miles) in area. The island is very mountainous, with Mount Rossel (also known locally as "Mbgö") as its highest peak at 800 meters. The indented coastline is mainly fringed by mangrove swamps. The island is covered by a tropical rainforest. A coral reef surrounds the island, extending 12 kilometers to the east and 40 kilometers to the west, and forming two lagoons. Rossel is 33 kilometers from the nearest westward island, Sudest (Vanatinai). Trade winds blow from the southeast from May to October and an irregular northwest monsoon blows from January to March, both of which bring rain. ~

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the population of Rossel Island in the 2020s was 9,200. In 1979, Rossel Island's population was approximately 3,000, with 800 people away from the island for work or school. The population density averages eight people per square kilometer, and the population is growing at a rate of three percent per year. Before 1950, the population was declining. ~

Language: The Rossel Islanders call their language Yelatnye (“language of Yela”) and refer to themselves as Yelatpi (“Rossel people”). Yelatnye is a Non-Austronesian (Papuan) language whose relationship to other Papuan languages of New Guinea and Melanesia remains uncertain. Rossel is the only island in the region where a Non-Austronesian language is spoken. Its similarity to the language of nearby Sudest Island is extremely low—only about 6 percent cognate overlap—and its phonology and grammar are notably complex, making it difficult for outsiders to learn.

History: Archaeological evidence suggests that Rossel Island has been inhabited since at least the Late Pleistocene. The Rossel Islanders are thought to represent the last surviving remnant of an early population that was replaced on neighboring islands by successive waves of Austronesian-speaking migrants. Around 2,000 years ago, pottery associated with the Lapita cultural tradition spread through the Massim region, likely accompanied by the introduction of a stratified social order linking smaller islands to emerging political centers. Although Rossel retained its Non-Austronesian language, its culture has been strongly influenced by its Austronesian neighbors.

The island’s first recorded contact with outsiders gave it a grim reputation: in 1858, 316 Chinese laborers bound for Australia were reportedly killed and eaten after a shipwreck on Rossel’s shores. The island was incorporated into the British (later Australian) Protectorate of Papua in 1884 and was gradually “pacified” over subsequent decades by government patrols. In 1903, a European trading family established a plantation that became the island’s economic hub for the next fifty years, radically reshaping local socioeconomic relations. Today the plantation is operated by Rossel Islanders themselves, and the island is more deeply integrated into the cash economy than its western neighbors. Christian missions arrived in the twentieth century, beginning with the Methodist (now United Church) mission in 1930, followed by the Catholic mission in 1947. At present, the western half of the island is predominantly United Church, while the eastern half is largely Catholic.

Rossel Islander Religion and Culture

Rossel religion today blends Christianity with enduring indigenous beliefs. According to the Joshua Project, about 88 percent of islanders identify as Christian, with 10–50 percent considered Evangelical. Two denominations—the United Church in the west and the Catholic Church in the east—divide the island geographically, but relations between them are generally harmonious. Christianity has been embraced not only as a spiritual system but also as a means of accessing health care, education, and economic opportunities. Although the government now administers schools and hospitals, these institutions remain located at former mission stations. [Source: John Liep, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Traditional beliefs persist alongside Christianity. Islanders continue to acknowledge local supernatural beings and communicate with them through spells, incantations, and occasional offerings. The primary deities (woyili) are thought to have lived on Rossel in the past, creating features of the landscape, introducing plants, and establishing aspects of culture such as sorcery. Some are regarded as subclan ancestors. These beings eventually withdrew into the underworld (teme) at specific sacred sites and may appear today in the form of snakes, dugongs, or crocodiles. Claims that they form a hierarchical pantheon are unsupported. Each sacred place is linked to one or two specific powers, which may bring blessings—such as crop fertility—or misfortunes such as illness. Formerly avoided except by initiated custodians, many sacred places have since fallen into neglect. Other traditional beings included ogres (podyem) with white skin and long hair and gnomes (kömba) said to live in hollow trees, although such figures are rarely reported today.

Death and Funerals: Burial is carried out in an L-shaped grave, usually within a shared cemetery serving several hamlets. In the past, bodies were first interred shallowly inside the house, later exhumed, and the skull displayed in the hamlet before being placed in a forest shelter. Deaths of prominent individuals once triggered accusations of sorcery against in-laws, who were required to compensate the bereaved by providing a cannibal victim for the ritual feast (hanno). Today, a week after burial, families hold the kpakpa mortuary feast, during which burial workers are compensated and traditional valuables are distributed among categories of relatives. Upon death, the spirit (ghötmi) leaves the body and travels either to Yeme, the mountain of the dead at the island’s western end, or—according to another tradition—to the underworld. Formerly, the spirits of cannibal victims were believed to go to Tpi, a mountain on the south coast. Ordinary ghosts (mbwe) are not especially feared, unlike the ghosts of those who were eaten. Unlike Sudest beliefs, Rossel spirits are not thought to interfere much in the affairs of the living.

Religious Practitioners and Ceremonies: Christian leadership consists of United Church pastors, usually from neighboring islands, and local Catholic catechists. Some men still possess inherited spells and ritual knowledge associated with sacred places (yopo) and secretly perform rites there, since the missions discouraged such practices. Illness is traditionally attributed to sorcery, breaches of sacred sites, or other ritual offenses. Treatments may include countermagic, sacrifices, herbal medicines, and ritual healing. Custodians of sacred sites are responsible for keeping them clean and performing rituals—such as libations and recitations of spells—at certain times of year or as needed. Other deity-related ceremonies include nighttime singing of sacred songs (ndamö), an exclusively male form of worship. Women gained a recognized role in ritual life only through Christianity.

Arts: Traditional Rossel carving—for example on canoes or lime spatulas—is typically plain, symmetrical, and nonfigurative, a style now largely replaced by the Massim spirals-and-scrolls aesthetic. Islanders weave several types of baskets, from large food carriers to fine containers for shell money. The island had no traditional musical instruments, though men sometimes drum on canoe hulls during ndamö performances. Dance traditions are varied; the most common is the tpilöve, in which men dance wearing distinctive skirts.

Rossel Islander Society and Family

Rossel society is structured around a highly developed system of ranked exchange in which a class of “big men” derives authority from control over high-value shell money. Researchers have described this arrangement as a kind of plutocracy. Social rank is not based on descent groups, but inequality is expressed through the greater influence of elders over youth and men over women. A “financial aristocracy” of exchange specialists and owners of high-ranking shell valuables forms the island’s dominant stratum. [Source: John Liep, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The basic domestic unit is the nuclear family, occasionally joined by unmarried young people or elderly dependents. This group manages everyday subsistence but relies on bilateral kin and affines for major tasks such as clearing gardens or building houses. Children are raised by the nuclear family along with grandparents and other older relatives. Practices vary, but sharing and cooperation are emphasized. While overt self-assertion is discouraged, individual autonomy is still valued. Important property includes fruit trees and ceremonial stone and shell valuables. Sons generally inherit from fathers and daughters from mothers, though the person who cared most for an elderly relative typically receives the largest share.

Marriage: Most clans and linked subclans prohibit marriage within their own ranks, including unions between first cousins. Marriage with a classificatory mother’s brother’s daughter is discouraged, while marriage with a classificatory father’s sister or her daughter is preferred, though fewer than half of recorded marriages follow this pattern. Local endogamy remains common, and elders often arrange marriages. Bridewealth is substantial and paid entirely in shell money, with cash excluded. Polygyny has declined under mission influence. Residence after marriage is mainly patrivirilocal, and divorce is uncommon.

Kinship: Rossel has roughly fifteen dispersed, totemic, matrilineal clans (pu). Their subclans (pughi) maintain mutual exogamy with one or more linked subclans from other clans. Subclan members do not necessarily live together but form localized segments. A broader cognatic category, yo, refers to the bilateral descendants of an ancestor or a person’s wider kindred. The kinship system is classificatory and of the Crow type, with alternate-generation terminology in one’s own and father’s lines. Like the Iroquois system, it distinguishes same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings but further differentiates between maternal and paternal sides. In Crow terminology, maternal kin receive more specific terms, while paternal kin are grouped under more general categories.

Political Organization: Rossel is divided into ten census villages that jointly elect seven local government councillors, supported by lower-level officials called komiti. Before colonial rule, leaders included warriors, ritual specialists, and powerful big men who commanded followers and controlled high-ranking shell valuables used in major payments, including those formerly associated with cannibalism. Missionization and pacification diminished the authority of traditional leaders, but older men with financial and ceremonial expertise continue to hold local influence. Modern councillors tend to be younger men with outside experience and broader language skills. Today Rossel Island is notably peaceful. Disputes are rare, and a major deterrent to antisocial behavior is fear of sorcery retaliation. Elders reinforce their dominance by controlling esoteric knowledge and the complex exchange system. Minor disputes are usually settled informally, while serious offenses are handled by the state through the island’s patrol post.

Government services include primary schools, a hospital, medical aid posts, an airstrip, a small wharf, and water-supply facilities. Politically, Rossel is represented in the Milne Bay Provincial Assembly and, together with the East Calvados chain and Sudest, forms the Yelayamba Local Government Council, electing seven of its sixteen members.

Rossel Islander Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Rossel Islanders practice swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture, rotating gardens between active use and fallow periods. Near the coast, former garden sites are often converted into small coconut plantations. Subsistence crops include taro, yams, sweet potatoes, cassava, bananas, and sugarcane. Sago flour is produced from the pith of the sago palm, and tree crops include coconuts and breadfruit. People also gather wild nuts and fruits, collect shellfish, hunt feral pigs and opossums, and fish using lines, spears, nets, dams, or occasionally plant-based poisons. Cooking methods range from boiling with coconut cream to roasting in embers and baking with hot stones. Commercial production centers on coconuts for copra and a small amount of coffee. Shell-necklace manufacture and labor migration provide additional cash income. [Source: John Liep, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Earlier settlements consisted of numerous small hamlets scattered along both the coast and interior; a 1919 census recorded 145 villages averaging ten residents. During World War II, the population was consolidated into about ten coastal villages, most of which later fragmented into hamlets or hamlet clusters, though people did not return to the interior. Settlement layouts vary, but hamlets commonly feature a carefully weeded square or street bordered by houses and marked by one or two stone sitting circles characteristic of the southern Massim. Traditional hamlets also included a seclusion house for menstruating or postpartum women. Hamlets are surrounded by banana groves, coconut palms, and other fruit trees. Earlier houses included barrel-roofed ground dwellings and pile houses entered through a trapdoor. Today, houses are generally built on posts with sago-palm roofs and walls of sago-leaf sheaths. Cooking is done beneath the house or on a clay hearth in the kitchen.

Men clear large trees for gardens, build houses and canoes, hunt, and fish. Women collect most shellfish and manage domestic work, including cooking and child care. Both sexes participate in planting, weeding, and harvesting, and they work together in sago processing. Rossel is renowned for its high-quality red-shell necklaces made from the Chama mollusk found in the western lagoon. Production expanded under trader influence in the early 20th century, and imported grinding stones are now used. These necklaces circulate in the kula exchange. Islanders construct their own houses, canoes, and dinghies, and a few larger boats have recently been built. Women produce finely made basketwork.

Land: With a small population, land pressure is minimal and disputes uncommon. Land areas are associated with matrilineal subclans, though stewards may belong to other clans. Use rights often derive from descent through both maternal and paternal grandparents. Mortuary payments made by a deceased person’s spouse’s relatives to their own kin help reaffirm such land claims.

Trade: The Catholic mission operates the main trade store, with smaller shops in many hamlets; otherwise, Rossel has no market system. Traditionally, Rossel engaged in visiting trade with Sudest, exporting shell necklaces in exchange for clay pots, pigs, and stone axes, though this network has declined. Internal exchange remains vibrant and is conducted through a complex system of shell valuables known as “Rossel Island money.” Two types exist: ndap (flat Spondylus pieces) and kö (sets of ten Chama disks on a string), both ranked into many grades. High-ranking ndap—rare treasures believed to be of divine origin—are individually named and now circulate only through inheritance. Lower-ranking ndap and kö still move through everyday transactions. Women own shell money and participate in exchanges but rarely organize major payments. Earlier interpretations of the system as “compound-interest lending” were based on misunderstandings of exchange rules. Other important valuables include ceremonial stone axes and shell necklaces. Cash is now used in some transactions.

Goodenough Island and Its History

Goodenough Island—at 9° S, 150° E—is the westernmost of the three rugged islands in the D’Entrecasteaux Archipelago of Milne Bay Province. Its mountains rise sharply to 2,440 meters, the highest peak in the archipelago, and its 777 square kilometers make it second in size only to Fergusson Island. Much of Goodenough is covered in dense rain forest, and the high interior remains uninhabited. Coastal plains and lower slopes consist largely of secondary forest and grassland. The climate is tropical, hot, and humid, with two main seasons: cooler southeasterly winds from May to October and the hotter northwest monsoon from December to March. Annual rainfall varies between 152 and 254 centimeters depending on location, with major droughts occurring once or twice a decade and hurricanes more rarely. Known as “Morata” on early maps, the island was renamed by Captain John Moresby in 1874. Early ethnographers Diamond Jenness and Rev. A. Ballantyne documented Bwaidoka communities in the southeast, while Michael Young later conducted in-depth research in Kalauna, a mountain village in the east-central interior. [Source: Michael W. Young , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Archaeological and genetic evidence indicates that the D’Entrecasteaux Islands have been inhabited for several millennia. Some mountain populations on Goodenough show distant genetic ties to mainland Papuans, while Austronesian migrants over the past two thousand years have profoundly shaped the island’s culture. Although the population is generally homogeneous, earlier distinctions existed between “people of the mountains” and “people of the coast,” a divide now blurred as many highland communities have resettled near the shoreline. All groups trace their origins to Yauyaba, a sacred hill on the east coast where humanity is believed to have emerged from underground.

In the 19th century, Goodenough was characterized by small-scale warfare and cannibalism. Because eating an enemy was considered the ultimate insult, a single incident could trigger escalating cycles of revenge. Alliances and hostilities were complex and not neatly defined by village or district boundaries; clans in neighboring communities could be mutual allies or adversaries regardless of broader political relations. Today, the close physical clustering of modern settlements can heighten minor conflicts, contributing to the island’s reputation for sensitivity to insult. Historically, disputes most often centered on food and women, though land issues are increasingly common.

European contact began with Moresby’s 1874 visit, followed by occasional stops by whalers, pearlers, and gold seekers. Administrator William MacGregor visited in 1888 during his inaugural tour of British New Guinea. The Wesleyan Mission, led by William Bromilow from Dobu, established a station at Wailagi in Bwaidoka territory in 1900. By then, coastal trade had already created steady demand for steel tools, cloth, and tobacco. A severe famine that same year pushed many men into contract labor abroad, initiating a strong tradition of migrant work that earned Goodenough Islanders a reputation as “the best workmen in Papua.” Local warfare and cannibalism persisted in remote areas until the early 1920s, when the first census was conducted and a head tax introduced.

World War II brought major upheaval. A small Japanese force briefly occupied the island in 1942 before being eliminated, after which the Allies constructed a large airbase on the northeast plain. After the war, the Australian administration paid relatively little attention to Goodenough, though a patrol post was established in 1960—partly in response to cargo-cult activity—and a local government council followed in 1964. Since Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975, Goodenough (together with the Trobriand Islands) has elected a representative to the national parliament and now also elects two members to the Milne Bay provincial government.

Goodenough Islanders

The people of Goodenough Island in Papua New Guinea are primarily subsistence farmers and speakers of several closely related Austronesian languages—Bwaidoka, Iduna, Diodio, and Buduna (Wataluma). Communities are often identified by these language names, including Bwaidoka, Iduna, Kalauna, Morata, and Nidula. Island households grow taro, yam, and sweet potato; fish along the coast and reef; and keep livestock for food and local exchange. Social life is organized through patrilineal descent, and most residents practice Christianity alongside long-standing ancestral beliefs. [Source: Michael W. Young , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The 2000 census recorded 20,814 people on Goodenough Island. In 1980, about 12,500 lived on the island and another 1,000 lived elsewhere. More than half resided in the southeast, where population density reached 38 people per square kilometer; densities elsewhere averaged around 10 people per square kilometer. [Source: Wikipedia]

Goodenough has four main languages—Bwaidoka, Iduna, Diodio, and Buduna—all members of the Milne Bay (“Papuan Tip Cluster”) branch of Austronesian languages. Bwaidoka, spoken by roughly 6,500 people, became the island’s lingua franca after its adoption by the Wesleyan (Methodist) Mission around 1900. Some groups, such as the Kaninuwa, use their own vernacular in the early years of primary schooling, supporting language maintenance.

old, new and mixed canoes at Beli Beli wharf on Goodenough Island Traces of War

Bwaidoga (or Mataitai) are an ethnic group living mainly along the southern coast. They farm, fish, and live in thatch-roofed houses clustered in small villages and hamlets. While Protestant Christianity—introduced by Methodist missionaries in the 1890s—is dominant, many animistic practices persist, sometimes even among church leaders. According to the Joshua Project, the Bwaidoga population in the 2020s was about 9,400, roughly 88 percent Christian, with 10–50 percent Evangelical. The group notes a continuing need for religious materials and teaching in the Bwaidoka language. [Source: Joshua Project]

Bwaidoga settlements number around twenty villages and numerous smaller hamlets located on narrow coastal plains. Access is primarily by air via a World War II–era airstrip or by sea, with boat travel from Alotau taking 12–15 hours. Storytelling is a favorite pastime, and village sports are popular—men typically play soccer, while women compete in netball, traveling between communities for matches.

Goodenough Islander Religion and Culture

Goodenough Island has been missionized for more than a century. Village churches—either United Church or Catholic—are found everywhere, and most islanders identify as Christian. Yet many long-standing practices endure. People continue to use magic for gardening, hunting, love, warfare, healing, and major life events, and numerous anthropomorphic spirits remain part of the cosmological landscape. Both ancestral spirits and immortal demigods are invoked in magical spells. Gardening in particular is surrounded by ritual and taboo, and every stage of cultivation has its own associated magic. Each community also keeps secret magical knowledge for suppressing appetite and preserving food, counterbalanced by sorcery capable of inducing insatiable hunger and famine. A key theme in indigenous cosmology is the power of bitter resentment, regarded as a potent and often dangerous force. Modern cargo cult movements on the island reflect these ideas, blending Christian concepts of sacrifice with older hero myths. [Source: Michael W. Young , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Death and Funerals: Burial customs vary across the island. Most communities use side-chambered graves, while some in the north practice secondary burial of bones in caves. Elaborate washing rites and food taboos are widespread, though specific details differ by locality, as do the sequences of mortuary feasts. Today most islanders conceive of the afterlife in Christian terms, but traditional beliefs persist. Funeral rites still acknowledge that the dead are thought to journey first to Wafolo on northern Fergusson Island, and from there—guided by a spirit who lives in the hot springs—they continue northward to Tuma, the ancestral island of the Trobriands.

Religious Practitioners and Healers: . Ritual specialists are those who inherit magical systems used to regulate appetite, food crops, weather, and other communal needs. Leaders typically employ garden magic on behalf of their groups, and most adults possess a small repertoire of inherited spells. Illness is commonly attributed to sorcery, broken taboos, spiritual attack, misdirected magic, or even malicious gossip. Healers—who are usually also sorcerers—use incantations, rub the body with medicated leaves, and spit chewed ginger onto the patient’s head. Since many ailments are believed to stem from social tension, curing may also require divination and the public airing of grievances.

Ceremonies: All life-crisis ceremonies involve distributing cooked and uncooked food. Other important events marked by ceremonial feasting include harvests, housewarmings, canoe launchings, and other inaugurations. In all such rituals, the sponsor who provides the food may not eat. A major ceremony in the past was manu-manua, a periodic prosperity rite during which magicians sat motionless for an entire day, reciting myths and spells intended to ward off famine.

Arts: Traditional woodcarving—producing bowls, drums, combs, lime gourds and sticks, war clubs, house boards, and canoes—followed the curvilinear Massim style. Music and dance were highly developed arts, and mouth flutes were once used in courtship. Rhetorical skill and storytelling remain valued abilities, supported by a rich oral literature of myths and folktales.

Goodenough Islanders Society and Family

Descent on Goodenough Island is patrilineal (passed down through the male line), with the "unuma" being the most important descent group. Clans are distinguished by their own origin myths, customs, and magical formulas. A typical village community comprises several local patriclans that occupy one or more adjacent hamlets. These hamlets consist of a number of genealogically ranked patrilineages. These clans are linked by marriage and exchange partnerships, and there may be additional cross-cutting ties based on historical enemy relationships. Village communities are also divided into nonexogamous moieties (social divisions allowing marriage within the group) for ceremonial purposes. These moieties form the basis of a reciprocal feasting cycle, though nowadays, such festivals tend to be promoted purely as memorials for deceased leaders. [Source: Michael W. Young , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The household, the basic economic and commensal unit, is usually composed of a married couple and their children, including any they are fostering. Adolescents, widows, and widowers may live in small houses of their own, but usually join other households for work and meals.Infants are breast-fed on demand and weaned abruptly around age two. Children are constantly handled by close kin, with the mother’s brother playing a key role and providing food gifts later repaid at adulthood. Hamlet children form peer playgroups and accompany adults to the gardens, where they make toy plots. Parents are generally indulgent but readily strike disobedient children. Early training stresses appetite control, though chewing betel nut is encouraged. Traditionally there were no formal initiations; today schooling weakens parent–child bonds.

Marriage is forbidden within either parent’s clan, though unions between exchange partners or distant cognates are favored. Most marriages occur within the same village. A marriage begins when the couple shares a first meal in the groom’s parental house. The bride is tested by her husband’s kin, while the groom performs bride-service. Exchanges of food ratify the union, but bride-price payments are often delayed for years. About a third of marriages end in divorce; weaned children usually remain with their father. Remarriage is straightforward, though bride-price must be repaid, and widows’ new husbands must compensate the deceased husband’s kin. Monogamy is standard, with only occasional polygyny. Marriage. Residence is patrivirilocal (living in the husband’s family home or community. t.

Kinship is patrilineal, which is different from most Massim groups. The unuma is a shallow patrilineage ranked by genealogical seniority. Several unuma make up a named, exogamous patriclan, each distinguished by its own origin myth, taboos, totems, and ritual knowledge. Clans belong to one of two ceremonial moieties. Hawaiian (generational) terminology is used: all parental-generation males are “Father,” all females “Mother,” and all same-generation kin are “Brother” or “Sister,” with additional distinctions by sex and relative age.

Political Organization: Competitive feasting replaces traditional warfare as a major arena of political action, linking communities through networks of food and pig debts. Leadership varies: warrior leaders were once prominent, but clan and hamlet leaders are ideally senior men, though energetic gardeners and skilled orators can rise to influence. Despite an egalitarian ethos, some clans hold special prosperity magic, giving their leaders unusual authority. In heavily missionized villages, church leaders often serve as community leaders.Wrongdoing was traditionally handled by kin groups, and people still prefer local settlement of disputes. Councillors mediate conflicts, but traditional sanctions remain important—public scolding, ridicule, ostracism, and sorcery. One powerful method of resolution is “fighting with food,” a dramatic postcontact adaptation of older conflict traditions.

Goodenough Islander Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Goodenough Island economy is centered on subsistence gardening. Staple crops include taro, yam, sweet potato, and sago, with coconuts, bananas, papayas, sugarcane, pumpkins, and other introduced foods grown alongside them. Yams dominate the agricultural calendar, and gardening is supported by extensive ritual and magic. Families also raise pigs and chickens, gather shellfish, and fish along the coast; wild pigs, birds, eels, and small game supplement the diet where available. Although some produce is sold locally or taken to markets in Alotau, copra remains the only significant cash crop, limited by poor transport and marketing. [Source: Michael W. Young , “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Villages lie along the coast, reef edges, and lower foothills. At contact, more than thirty small districts dotted the island; resettlement programs in the 1920s consolidated many mountain communities near the coast. Today, twenty-three census wards represent the modern successors to these older districts, with average village populations around 500. Hamlets cluster around circular stone sitting platforms that symbolize lineage continuity. Houses are raised, rectangular structures with two or three rooms and kitchens. Two styles remain common: a warm, pandanus-walled hill style and a cooler coastal type with sago-midrib walls. Both use black-palm floors and sago-leaf thatch. While imported materials are increasingly available, many communities continue to build with traditional timber and palm resources.

Work has traditionally been divided by sex. Men clear new gardens, build houses, hunt, fish, butcher pigs, and take charge of large ceremonial cooking. Women plant and harvest gardens, perform most weeding, prepare food, fetch water, care for children, and raise pigs; they also gather shellfish. Both sexes collect firewood and tend daily household tasks. Wage labor has long been important: since the early 1900s, many young people—formerly almost all young men—have worked as migrants, sending part of their earnings home. Increasing numbers of islanders now work in towns as clerks, teachers, and public servants. Traditional tools included stone axes, obsidian and bamboo knives, black-palm spears and clubs, single-outrigger canoes, digging sticks, slings, and netting made from plant fibers. Basketry and mat-weaving were widespread, with only limited craft specialization outside canoe building, hunting nets, and pottery.

Trade: Goodenough was largely self-sufficient and only lightly plugged into wider Massim trade circuits due to limited canoe technology. Most long-distance goods came from traders from western Fergusson, the Amphletts, the Trobriands, and Cape Vogel. Items exchanged included clay pots, pigs, yams, sago, betel nuts, arm shells, nose shells, baskets, and decorated combs. Interdistrict ceremonial visits involved hereditary trade partners and required the passing of gifts to third parties, a system bearing similarities to the kula.

Land and Inheritence: Clearing and planting virgin forest establishes permanent group rights to land. Garden and residential land is inherited patrilineally and is considered inalienable. A hierarchy of corporate rights exists within each clan, but in practice, sibling groups function as the main landholding units. Sons inherit land and fruit trees from their fathers; daughters inherit as well but usually use their husband’s land, and their children gain access only through compensatory payments to her brothers. In some areas, garden plots can temporarily transfer after a death as payment to non-agnatic buriers, later reclaimed through reciprocal burial service. The spread of coconut planting for cash income has made land claims increasingly rigid. Property—including land, trees, magic, and clan regalia—is inherited through the male line. Eldest sons receive the core of their father’s property and are expected to distribute portions to siblings, though ritual knowledge is usually more tightly held. Men without close male heirs may pass land or magic to a sister’s sons, sometimes causing later disputes. Women may own land, pigs, and ritual objects, but decisions about their use typically require the approval of male relatives. As in most of Melanesia, wealth is widely dispersed at death, preventing the formation of hereditary rank.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025