Home | Category: Island Ethnic Groups

TROBRIAND ISLANDERS

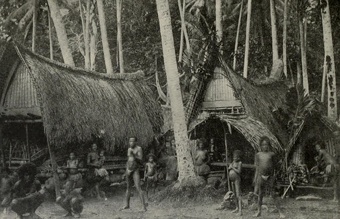

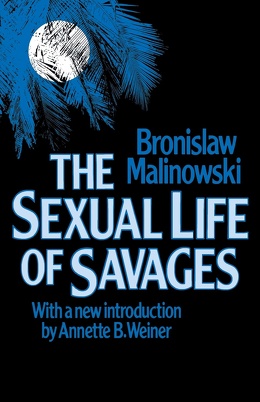

The Trobriand Islanders are the residents of the Trobriand Islands, a small group of coral islands about 200 kilometers (125 miles) north of the eastern tip of New Guinea. These islanders were the subjects of Bronislaw Malinowski’s "The Sexual Life of Savages in Northwestern Melanesia", a famous anthropological work published in 1927. Old-timers that remembered Malinowski in the 1990s called him the “man who asked questions”. In his studies Malinowski reported that the Trobriand Islanders were "keen on fighting" and they often fought "systematic and relentless wars" as well as engaging in unusual sexual practices.

The Trobriand Islander traversed large expanse of open ocean in canoes to trade and fight. They often traveled great distances over open ocean to trade shells in something called the kula game. The shells which look worthless to westerners are given from one group of islanders to another, who in turn pass them on to other islanders. The islanders in this region have been doing this for hundreds of years and the their shells are as valuable to them as four foot yam, which are greatly treasured. Author Paul Theroux asked one islander how he navigated the open ocean,"We can smell the islands," he replied.

Many sea creatures which frighten most people are mere nuisances to the Trobrianders. Huge salt water crocodiles don't worry them, "Now and then they eat our dogs," Theroux quotes the islands as saying. Sea snakes, he reports, are played with by bored fisherman who like to tweak their tails. And if a shark heads in their direction they go "hoop, hoop, hoop!" to frighten it away.

Language: Trobriand Islanders speak Kilivila, a language that belongs to the Milne Bay Family of Austronesian languages. Although Kilivila is spoken on some other Massim islands, the main speakers are Trobrianders. Mutually intelligible local dialects are used, in which different phonological rules are applied without affecting the syntax. Since the time of first contact, many English words have been added to the Kilivila lexicon. Tok Pisin is rarely heard, although, along with Motu, it is often learned by Trobrianders who have lived elsewhere in Papua New Guinea. English is taught in the local high schools and the Kiriwina High School, but less than half of the young people attend school.[Source: Annette B. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROBRIAND ISLANDER CULTURE: CUSTOMS, MATRILINEAL SOCIETY, SEX AND YAMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE TROBRIAND ISLANDS AND MASSIM REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ISLANDERS OF NORTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA ON MANAM, WOGEO AND MANUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA ISLANDERS OF MASSIM, MILNE BAY AND DOBU, ROSSEL AND GOODENOUGH ISLANDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EAST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — THE BAINING AND TOLAI — AND THEIR CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES AND DANCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WEST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — NAKANAI, AROWE — AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MASKS AND ART OF NEW BRITAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

NEW IRELAND ETHNIC GROUPS — MADAK, LESU, AND LAK— AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM NEW IRELAND: MALAGAN, FUNERARY FIGURES AND DRUMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOUGAINVILLE ISLANDERS — SIWAI, TINPUTZ, NAGOVISI — AND THEIR HISTORY, SOCIETIES AND CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NASIOI OF BOUGAINVILLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

NISSAN ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Trobriand Islands

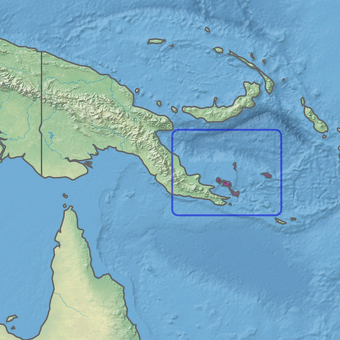

The Trobriand Islands are situated about 384 kilometers by sea from Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea, in the northern tip of the Massim. Their coordinates are approximately 8°30 S, 151° E. Kiriwina is the largest and most heavily populated island. It is 40 kilometers long but only 3.2 to 12.8 kilometers wide. The other islands are much smaller. Except for Kitava, where cliffs rise sheer for 90 meters, the islands are relatively flat, crosscut by swampy areas, tidal creeks, and rich garden lands that abut rough coral outcroppings. Reefs may extend up to 10 kilometers offshore; anchorage is often dependent upon high tides and careful navigation. Temperatures and humidity are uniformly high. Rain showers, heavy but usually of short duration, average from 25 to 38 centimeters each month. Yet unexpected droughts can occur, causing severe food shortages. [Source: Annette B. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The Trobriand Islands were named after Denis de Trobriand, the first lieutenant in one of D'Entrecasteaux's frigates when this group of populated atolls and hundreds of islets was sighted in 1793. Traditionally, Kiriwina and three other neighboring islands — Kaileuna, Kitava, and Vakuta — were each divided into discrete, named political Districts. Although these divisions still exist, the islands now form a more unified political unit as parts of Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. |~|

At the beginning of the 20th century, the population in the Trobriands was about 8,000, but by 1990 it had increased to approximately 20,000. Although many young people leave the islands to find wage labor or to attend technical schools or the University of Papua New Guinea, a large percentage of them eventually return to resume village life.

History of the Trobriand Islands

The origin stories for each matrilineage describe how different groups arrived in the Trobriands from under the ground or by canoe and claimed garden and hamlet lands as their own. These claims were often contested by others who arrived later, so that subdivisions of matrilineages occurred. [Source: Annette B. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

American whalers arrived in the northern Massim in the 1840s. In the 1860s, blackbirders from Queensland made frequent kidnapping excursions to other nearby islands. In the 1890s, Germans regularly sailed from New Britain to buy tons of Trobriand yams, while wood carvings, decorated shells, and canoe prows were already part of museum collections.

In the early 20 century, the Methodist Overseas Mission (now the United Church Mission) established itself on Kiriwina, followed in 1905 by the arrival of Dr. Rayner Bellamy, the first Australian resident government officer. Bellamy spent ten years in charge of the government station on Kiriwina and assisted C. G. Seligman with ethnographic information during Seligman's Massim research. Following his mentor, Bronislaw Malinowski stopped on Kiriwina and then stayed for two years between 1915 and 1918. The Sacred Heart Catholic Mission arrived in the 1930s

During World War II all Europeans living in the Trobriand Islands were evacuated. Australian and U.S. troops set up a hospital and two airstrips on Kiriwina. Although no battles were fought the area served as a staging ground for planes en route to Rabaul and the Coral Sea. In 1950, when Harry Powell arrived to conduct ethnographic research, surprisingly few cultural changes had occurred. Even in 1990, the kula interisland exchange of arm shells and necklaces, yam harvests and women's mortuary distributions were all very much alive.

Trobriand Islander Religion

The Trobrianders believe in spirits that reside in the bush and cause illness and death. However, their greatest fear is sorcery. Some people are believed to have knowledge of spells that can "poison" a person, and these experts can be petitioned to use their powers on behalf of others. Counterspells are also known, and chemical poisons obtained elsewhere are thought to be prevalent. Additionally, magic spells are chanted to fulfill many desires, such as controlling the weather, finding love, becoming beautiful, becoming an expert carver, becoming a skilled yam gardener, and becoming a skilled sailor. Mission teachers have not disrupted the strong beliefs in and practice of magic. Recently, however, villagers from two hamlets introduced a new fundamentalist religion whose tenets negate the practice of magic. [Source: Annette B. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Most villagers own some magic spells, but only certain women and men are known to have the most sought after and powerful spells for gardening, weather, and sorcery. The most powerful spells are owned by the Omarakana chief. Some villages have resident mission catechists who conduct Sunday church services.|~|

Christians that live on the Trobriand Islands follow a few rituals that aren't exactly spelled out in the Bible. To make sure a boy grows straight and tall, for example, the small boy is revolved around burning grasshopper's eggs placed in a coconut shell.

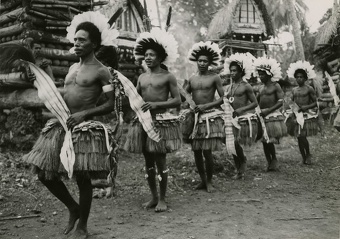

Trobriand Islander Ceremonies, Funerals and Rituals

The Trobriand Islanders perform a series of rituals for pregnant women. For several months after the birth, the mother and infant are secluded. Their reemergence is celebrated with a feast. The biggest celebrations take place during the annual harvest season, after the yams are harvested and stored in the yam houses. Under the leadership of a chief or hamlet leader, a village may hold cricket matches, dances, or competitive yam exchanges. These activities culminate in a large feast for the participants. Kula activities are surrounded by many rituals and celebrations. [Source: Annette B. Weiner, Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania, edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996.

Trobriand Islanders believe that when a person dies, their spirit goes to live on the distant island of Tuma, where ancestors continue to exist. At the end of the harvest period, the ancestors of a matrilineage return to the Trobriands to check on their relatives. The mourning and exchanges following a death are the most lengthy and costly of all ritual events. When someone dies, an all-night vigil is held during which men sing traditional songs and the deceased's spouse and children cry over the body. After the burial, a series of distributions of food and women's wealth takes place. Then, the close relatives of the deceased's spouse and father shave their hair and/or blacken their bodies. The spouse remains in seclusion.

About six months later, on Kiriwina, the women of the deceased's matrilineal line hold a huge distribution of skirts and bundles of banana leaves to repay the hundreds of people who mourned. (On Vakuta Island, only skirts are exchanged.) The woman who distributes the most wealth is considered a great woman. Today, trade cloth is sometimes used instead of bundles, and such cloth plays a central role in women's distributions held in the capital by Trobrianders living there. There are annual distributions of yams, pork, and taro pudding.If a harvest is particularly large, a village-wide distribution is held to honor all the recently deceased from a clan. |~|

Trobriand Island Big Men, Politics and Social Organizations

Trobriand Island big men traditionally inherited their positions and could be deposed only through war. There was a "paramount chief" with power over dozens of villages and several thousands people. Big men and chiefs wore different kinds of shell ornaments that defined their rank. The paramount chief was like a super big man whose power rested in his ability as "great provider" rather his control of weapons and territory. He also firmed up his position by marrying the sisters of leaders of important clans and subclans. Some chiefs had a dozen wives and wealth was accumulated through gifts of yams from his brothers-in-laws to his wives. These yams were in turn were used in great feasts (conferring the super big man’s position as a “great provider") and pay the salaries of canoe builders, artisans, magicians and servants It was forbidden for common people to sit or stand at position higher than the chief. Malinowski described one group of people dropping down "as if mowed down by a hurricane" when the arrival of an important chiefs was announced.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Trobrianders are divided between those born into chiefly and commoner matrilineages. Chiefly matrilineages, ranked among themselves, own rights to special prerogatives surrounding food prohibitions and taboos that mark spatial and physical separation as well as rights to wear particular feather and shell decorations and to decorate houses with ancestral designs and cowrie shells. For all villagers including chiefs, the locus of social organization is the hamlet with networks of social relations through affinal and patrilateral (on the father’s side) ties to those living in other hamlets within the same village. Women and men also consider themselves kin to those whose ancestors came from the same place of origin. Traditionally, only members of chiefly lineages and their sons participated in kula, but now many more villagers (although by no means all) engage in kula. Chiefs remain the most important kula players. [Source: Annette B. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Each ranking matrilineage is controlled by a chief but the highest-ranking chief is a member of the tabalu matrilineage and resides in Omarakana village. The most important chiefly prerogative is the entitlement to many wives. At least four of each wife's relatives make huge yam gardens for her and this is the way a chief achieves great power. But if a chief is weak, he will have difficulty finding women to marry. The villagers of all the islands elect councillors who are members of the Kiriwina Local Government Council. Chiefs sit at the Council of Chiefs, and the Omarakana chief presides over both councils. Chiefs' kula partners are the most important players in other kula communities, and chiefs have the potential to gain the highestranking shells. |~|

Disputes most often arise over land tenure, usually before the time of planting new yam gardens. Other causes of conflict concern cases of adultery, thefts, physical violence and, more rarely, sorcery accusations. The Council of Chiefs arbitrates most problems but some cases are referred to formal courts. |~|

Because of the many intermarriages that occur within a village, conflicts are quickly resolved by public debate. Warfare between village districts was a common occurrence prior to colonization. Such fighting, undertaken by chiefs, most often took place during the harvest season when political power or its absence was exposed. Today, fights sometimes erupt for the same reasons, but the presence of government officials usually holds these incidents in check. The most dangerous conflict is the traditional yam competition where the members of one matrilineage line up their largest and longest yams to be measured against the yams brought together by the members of a rival matrilineage. Lengthy speeches made by intervening kin or affines will Usually stop the competition from proceeding. Once a winner is declared, the losers become the most dangerous enemies of the winning matrilineage for generations.

Agriculture and Economic Activity Among Trobriand Islanders

Slash-and-burn agriculture produces large annual harvests of yams. Taro, sweet potatoes, bananas, sugar cane, leafy greens, beans, tapioca, pumpkins, coconuts, and areca palms are also grown. The pig population is small; pork is usually eaten only on special occasions. Few chickens are raised, and fish is the main source of protein. There is almost no game, except for birds, which are sometimes hunted; children catch and eat frogs, grubs, insect eggs, and mollusks collected from the reefs.

Since colonization, government attempts to develop cash crops have failed (except for a period of copra production), and only in recent years has a local market been established on Kiriwina, run by women. Fishing provides a cash income for many coastal men, and a fishing cooperative has been successful on Vakuta Island. In the 1970s, weekend tourist charters resulted in increased carving sales, but over the past decade tourism has declined dramatically. Ebony wood, once prized for fine carvings, is depleted and must be imported from other islands. A few Kiriwinans own successful craft shops; a guest lodge and two other craft shops are owned and operated by expatriates. Today, remittances from children working elsewhere in the country are the villagers' main source of income. Women's bundles of dried banana leaves serve as a limited form of currency when villagers buy food, tobacco, kerosene, or cloth from the trading store and sell these items to other villagers for payment in bundles. This allows those without cash to purchase Western goods. [Source: Annette B. Weiner, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

Most garden and other tools are made of metal. Canoes are still built in the traditional way, with elaborately carved prows. Pandanus sleeping and floor mats, baskets, and armbands are woven, as are traditional women's skirts, which, although worn only on special occasions, are considered wealth and are essential for mortuary exchange. Bundles of dried banana leaves are also made by women and are considered wealth for mortuary exchanges. A few men still make arm shells for kula exchange, as well as jewelry such as spondylus earrings and necklaces. |~|

Stone axe blades are the wealth of the men; in the last century the stones were traded from Muyua Island and polished in the Trobriand Islands. Large cooking pots, also used in local exchange, come from the Amphlett Islands. Canoes from Normanby and Goodenough Islands regularly arrive with sacks of betel nuts for sale at the Kiriwina wharf. Kula voyages also allow partners to bring back exotic goods from other islands. |~|

Women and men work together to clear new garden plots. The men are responsible for planting the yams, staking the vines, building the garden fences, and harvesting. Women produce other garden foods, although occasionally a woman decides to start her own yam garden. Men fish and butcher pigs. Women do the daily cooking, while men prepare pork and cook taro pudding for feasts. Both men and women weave mats, but only women make skirts and the banana leaf bundles that are the women's wealth. |~|

Hamlet, garden, bush, and beach lands are generally owned by a founding matrilineage and are under the control of the lineage chief or hamlet leader. These men grant rights of residence and land use to others, such as their sons, who are not members of the matrilineage. Land disputes are common, and because court proceedings are public, they are fraught with tensions that sometimes lead to fighting. Knowledge of the history of the land from the time of the first ancestors legitimizes a person's claim, but competing histories make it difficult for the arbitrating chiefs to make decisions.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: CIA World Factbook, 2023; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025