Home | Category: Island Ethnic Groups

NEW IRELAND

New Ireland is a long, narrow island in Papua New Guinea, known as Niu Ailan in Tok Pisin and Latangai in local usage. Named after the European island of Ireland, it covers about 7,404 square kilometers (2,859 square miles) and has roughly 120,000 inhabitants. It is the largest island in New Ireland Province and lies northeast of New Britain, across Saint George’s Channel in the Bismarck Archipelago. Kavieng, at the island’s northern tip, serves as the provincial capital. The Bismarck Sea borders the island to the southwest and the Pacific Ocean to the northeast.

Often described as musket-shaped and located just two to five degrees south of the equator, New Ireland stretches about 360 kilometers (220 miles) in length but narrows to 10 to 40 kilometers (6 to 25 miles) across. A steep central mountain spine dominates the landscape. Mount Taron in the Hans Meyer Range is the highest point (2,340 meters, 7,680 feet), with other ranges including Tirpitz, Schleinitz, Verron, and Rossel. New Ireland straddles two ecoregions: lowland rainforests from sea level to 1,000 meter and montane rainforests above that elevation. Lowland deforestation is widespread across New Ireland, New Britain, Bougainville, and many mainland areas; by 2002, 63 percent of accessible forests had been logged or degraded.

New Ireland Province includes the island of New Ireland and numerous smaller islands, such as the Saint Matthias Group (Mussau and Emirau), New Hanover, Djaul, the Tabar Group (Tabar, Tatau and Simberi), Lihir, the Tanga Group (Malendok and Boang), and the Feni Islands (Ambitle and Babase), which are also known as the Anir Islands. The province's land area is around 9,560 square kilometers (3,690 square miles). The sea area within New Ireland Province's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is around 230,000 square kilometers (89,000 square miles).

History: The first settlers arrived about 33,000 years ago, likely from mainland Papua New Guinea, followed by Lapita peoples around 3,000 years ago. Three cultural traditions—Kabai, Malagan, and Tubuan—are especially prominent. The Dutch explorers Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten first recorded the island in 1616. Bougainville visited in 1768, and whaling ships stopped frequently in the 19th century. In the 1870s–80s the Marquis de Rays attempted several failed expeditions to create a colony called “New France,” resulting in heavy loss of life. From 1885 to 1914 the island, then known as Neumecklenburg, formed part of German New Guinea, with profitable copra plantations and a coastal road—now the Boluminski Highway—established under administrator Franz Boluminski. Australia assumed control at the start of World War I, restored the name New Ireland and administered New Ireland as a League of Nations mandate from 1921 until the Japanese occupation of 1942. After Japan’s defeat, Australia resumed governance in 1945, and New Ireland became part of the Territory of Papua and New Guinea in 1949 under United Nations oversight until Papua New Guinea became independent in 1975.

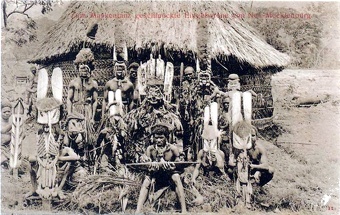

Ethnic Groups and Art: New Ireland is home to several distinct indigenous ethnolinguistic groups, including the Lesu, Nokon, Mandak, Usen, Barok, Nusu, and Lavongai. These groups lack social cohesion, and prior to European dominance, they were often at war with one another, as were villages within groups. Contact between villages is mainly limited to attending ceremonies together. The island is also renowned for its ceremonial arts, especially: 1) Malagan – elaborate funerary carvings and performances originating in the Tabar Islands and now central to northern New Ireland identity; 2) Tatanua – dance ceremonies featuring distinctive crested masks, typically rented from specialist carvers; and 3) Kulap – chalk limestone funerary figures associated with mortuary rites.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ART FROM NEW IRELAND: MALAGAN, FUNERARY FIGURES AND DRUMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EAST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — THE BAINING AND TOLAI — AND THEIR CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES AND DANCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WEST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — NAKANAI, AROWE — AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MASKS AND ART OF NEW BRITAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOUGAINVILLE ISLANDERS — SIWAI, TINPUTZ, NAGOVISI — AND THEIR HISTORY, SOCIETIES AND CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NASIOI OF BOUGAINVILLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

NISSAN ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, BIG MEN POLITICS, ECONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDER CULTURE: CUSTOMS, MATRILINEAL SOCIETY, SEX AND YAMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE TROBRIAND ISLANDS AND MASSIM REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ISLANDERS OF NORTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA ON MANAM, WOGEO AND MANUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA ISLANDERS OF MASSIM, MILNE BAY AND DOBU, ROSSEL AND GOODENOUGH ISLANDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Traditional Sexuality in New Ireland

According to “Growing Up Sexually”: Kingston (1998, 2003) notes that from an early age brothers and sisters must avoid each other, and may not mention each others names but “The age seems to be debatable and increasingly of lessening severity, but certainly by puberty”. Normally a boy would go and sleep in the men's house from around 12 (depending on the accommodation available), and if a girl was reaching puberty the father would sleep in the men's house (or alternatively the daughter would sleep with other female relatives)”. Genitals are within the realm of shame; thus, “a child [who] saw their father or mother naked during washing, is [a fact] regarded as pial, a lowgrade betrayal of secrets”. “My impression was that girls became sexually active from around the age of 14 or 15 and boys from a little older. By all accounts, a fair amount of pre-marital sex goes on, and a moderate amount of discrete extra-marital liaisons”. [Source:“Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Among the New Ireland Darabi, betrothal took place in infancy “or at an early age” (Wagner, 1983). Shame surrounds all sex knowledge and sex education is anticipated as seduction, so that fables are told instead of facts. In 1889, Rev. Benjamin Danks wrote: In New Ireland, girls of eight and nine were placed in narrow cages until the age of marriageability, somewhere after age 15.

“Menstruation, variously known as rei kaben (seeing the moon), or samsilik (sick blood), is…seen as caused by intercourse, the blood being discarded (or inadequately congealed?) semen. First menses are in fact meant to take place during the girls seclusion in the dal ritual (see Ch.6), during which spirits and suitors are attracted to her before she is married off. The moon (in whom Siar people, like us, see a man) is also seen as 'cutting' the girl, or being causative in some rather vague way…Singing of being made to bleed by being bitten or eaten by a sea snake, in a rite where girls are transformed into sexually active women and menstruation is 'produced', is very thinly disguised reference to a, presumably spirit, phallus deflowering the girl and, given the correlation the Lak make between the two, initiating menstruation…The most direct statements we have of the cause of the menstruation are the references to phallic sea snakes. They cause bleeding by eating the dal and uninitiated girls are encouraged to pull them to them. Earlier we saw how other 'sea-snakes', paloloworm, were similarly attracted to pregnant women. But other entities are also attracted to the dal in an analogous manner. There are various birds who come to her, and, amongst other actions, 'shake the goh'. We also have a succession of spirits, pidiks and men coming to her: from the inchoate and thoroughly inhuman sounds and otherworldly visions of the night pidiks, to the still pidik and ancestral, but visibly human and male malerra, to, presumably and eventually, an all too human suitor or husband. All these, the snakes, the birds and the various pidiks clearly belong to the same family of representations, most easily classifiable as spiritual, ancestral and male. Two things are clear about the selection of these images. Firstly, the most phallic form is most directly connected with menstruation, clearly linking it with physical as well as spiritual penetration. Secondly, the least human and least bound to form presentations were during the night and during the dals seclusion; the half-human malerra were presented in daylight when the girl herself was no longer in enclosed obscurity, but was still in the role of dal; and fully human men are subsequently taken as lovers when she herself is fully restored to the world of women”.

Dal, which, “as a word, refers both to the girl or woman and the ritual they undergo. It also means a young, sexually attractive woman and is the name given to several such characters in various stories in which Suilik (the main culture-hero) or a wallaby (an animal associated with male display and decoration) attempt to take her as a sexual partner. Sexual attraction is a major theme of the dal ritual and the production of a gendered and sexual woman from a non-sexual and androgynous child attracts male spirits in a way similar to that predicted by Strathern’s ‘Melanesian aesthetic’ (1988)…The dal is an idealized cultural image: all young women have breasts and menstruate, but not all are dal, some are kurmakmak and some, having only completed the exchange part of the rite, only nominal dal. The dal is an icon of a sexually attractive, fecund, ‘fat’ young woman who has developed breasts and started menstruating”.

Madak

The Madak live in central New Ireland. Also known as the Mandak, they speak various dialects of the Madak language, which is part of the Austronesian family, and traditionally rely on gardening, fishing, and working with plantations for income. The Madak are part of the wider New Ireland culture, which includes practices like Malagan, elaborate ceremonies for honoring the dead through art and feasting. “Madak” and “Mandak” are linguistic-cultural designations. "Mandak" means "boy" or "male" and is used by New Irelanders to refer to those speaking the various dialects of Madak. Further sociocultural distinctions are made by reference to particular Madak villages. [Source: Brenda Johnson Clay, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Madak live on the east and west coasts and in the interior on Lelet Plateau on New Ireland — between 3°6 and 3°20 S and 151°47 and 152°8 E. This tropical area experiences a wet season from December to May, dominated by northwest monsoon winds, and a dry season from May to October, dominated by southeast trade winds. These seasons are divided by transitional, calmer, and more humid weather. Rainfall varies considerably according to local topographic conditions, and periodic drought is a potential problem in some coastal areas. Mean monthly temperatures range from the high 20s to about 32°C.

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Madak population in the 2020s was 9,300. In the 1960s, the Madak population numbered 3,324, with around 500 residing in the Lelet region of the interior. From around 1920 to 1950, New Ireland experienced a population decline due to contact with Westerners. By the late 1950s, the population had stabilized and begun to grow in some areas. Due to the loss of all census data for New Ireland during World War II, government records are only available from 1949 to the present. A census of east coast villages conducted by E. W. P. Chinnery in 1929 indicates larger village populations than the 1949 government census."

Language: Madak, also known as Mandak, is an Austronesian language spoken in New Ireland. The Library of Congress subject classification uses Mandak. Madak has five dialects and is classified with Lavatbura-Lamusong in the Madak Family. Linguistic variation is also found at the subdialect level from village to village.

History: Little is known about the Madak prior to Western contact. Until the 1920s—when colonial authorities imposed pacification—sporadic warfare took place both within and between villages. Today’s coastal communities include people who trace their origins to long-standing settlements as well as those whose ancestors relocated from inland areas at the urging of German and later Australian colonial administrations in the early twentieth century.

From the seventeenth to the eighteenth centuries, New Ireland was visited by Dutch, English, and French explorers, as well as blackbirders. Germany claimed the island as a colony in 1884, renaming it Neu Mecklenburg, and by the early 1900s German and English settlers had established coconut plantations on land taken from local communities with little compensation. During this period, the German administration conscripted local labor to build a nearly 200-mile coastal road from Kavieng to Namatanai.

Economic changes followed colonial rule. In the 1950s the Madak began establishing their own coconut plantations for copra production and added cacao as a second cash crop in the 1960s. Christian missions have also left a strong imprint: Methodist work began in the late nineteenth century, with Roman Catholic missions expanding in the 1910s. Today, traditional cultural knowledge is increasingly affected by mixed marriages, schooling outside the local language area, and widespread use of Tok Pisin, the national lingua franca.

Madak Religion and Culture

Nalik cult figure (used at the Uli festivals) from Madak Region, 19th century, made of wood, cowrie shell, operculum of the turban snail, bast fibers, color pigments

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 95 percent of Madak are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent. Mission work began in the Madak region in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and today most residents are nominally affiliated with either Methodist or Roman Catholic churches. Alongside these Christian identities, many Madak continue to hold beliefs in a world inhabited by diverse nonhuman spirits, many of which are considered dangerous. Each clan is associated with one or more powerful spirits embodied in animals, marine life, or features of the clan’s land. Spirits of the dead—especially those who died violently—are also regarded as potentially hazardous. A pervasive, unseen power or energy is believed to be manipulable through magic spells, and concerns about both beneficial and harmful forms of magic are woven into daily life. [Source: Brenda Johnson Clay, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Death and Funerals: Madak ideas about death blend Christian teachings with pre-Christian beliefs. Traditionally, the spirit of someone who died violently becomes a restless wanderer, while the spirit of one who died peacefully was once thought to travel to nearby small islands. Both types of spirits may assist the living by providing magical power, ritual knowledge, or new song-dance forms.

Religious Practitioners: Most adults—men and women—are thought to possess some knowledge of magic spells, while only certain men can perform the more potent forms of sorcery, ritual empowerment, and specialized magic such as shark-catching, calming the sea, or weather control. Village church leaders are typically drawn from the local male population.

Ceremonial Life and the Arts center on mortuary feasts, which range from simple burial rites to later commemorative feasts for an individual, as well as large clan-sponsored ceremonies featuring dancing and the distribution of pigs, taro, and sweet potatoes. The principal artistic expression in the area is malagan production. Malagan ceremonies occur in the region, though unevenly since the 1950s. Malagan refers both to elaborately carved or woven masks, figures, and friezes and to the ritual performances associated with them, usually within major mortuary events. Men’s and women’s songs and dances also play a central role in the concluding stages of major mortuary ceremonies.

Madak Society and Family

Madak society has traditionally been matrilineal (descent through the female line) and has been shaped by a series of oppositions that become salient in different contexts. Moiety (each of two parts of a divided thing) and clan exogamy (marrying outside a village or clan) are stressed. At the broadest level, the two matrilineal, exogamous moieties function as complementary units, linked through the exchange of nurturance expressed in men’s roles in procreation and childrearing. Similar contrasts can appear among clans, lineages, and individuals. Shared membership in a moiety, clan, or lineage emphasizes mutual nurturance. A hamlet is identified with and owned by a lineage, ideally under the authority of its senior male, who oversees the men’s house. Although a hamlet belongs to one lineage, its residents may include members of other clans connected through marriage or paternal ties. Social units are not territorially compact and may be dispersed across several villages, yet each retains a central identity anchored in a single hamlet and its men’s house, where lineage members are buried. [Source: Brenda Johnson Clay, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Domestic arrangements among the Madak have traditionally varied. Separate households exist for single adult women—divorced, widowed, or unmarried—alongside those of nuclear families. Single men typically reside in the men’s house. Both parents discipline their children, usually verbally, with occasional use of a switch, and older siblings exercise some authority over younger ones. Adoption is common, usually within close kin. Male youths, from about age twelve into their early twenties, enjoy considerable freedom and carry few responsibilities. Most children attend local schools through about age twelve, after which some continue to boarding secondary schools and later to college or technical training. Ideally, land and certain forms of magic pass matrilineally, though individuals may also inherit land or magic spells from their fathers.

Marriage: Before mission influence, both polygyny and polyandry were accepted, though neither was common. Moiety and clan exogamy are emphasized, but villages themselves are not exogamous, and marriages within the village are often preferred. A bride-price is provided by the husband’s lineage to the wife’s lineage. Postmarital residence varies; couples typically move several times during their marriage. Senior men of a sibling group are expected to reside in their lineage hamlet. Divorce is permitted, with young children generally remaining with their mother.

Kinship: Madak individuals belong at birth to their mother’s lineage, clan, and moiety. There are no recognized formal relationships among clans of the same moiety or among lineages of the same clan. Moieties are exogamous, and kinship is framed in terms of shared or exchanged nurturance between individuals and groups. A man’s relationship to his offspring is expressed through nurturance, and at death his children and spouse (or, for a woman, her spouse) give wealth to the deceased’s clan in acknowledgment of nurturance received. Kinship terminology is a variant of the Iroquois system, distinguishing same-sex from cross-sex siblings of parents. Father’s brothers and mother’s sisters are addressed by parental terms, while father’s sisters and mother’s brothers receive nonparental titles commonly translated as “aunt” and “uncle.” Parallel cousins are addressed as siblings; cross cousins are classified as cousins and are not considered siblings.

Political Organization is centered on big-men, though all middle-aged and older men are recognized as having some degree of political capacity. The senior man of a lineage represents his group in land disputes, feast sponsorship, and formal exchanges. Villages typically include one or more men regarded as particularly strong or powerful, who are active in organizing major events and fostering consensus in large-scale cooperative activities. Their reputations often extend beyond their home communities.Since the early colonial era, appointed and later elected officials—at village, regional, and, after 1975, national levels—have participated in local governance. At times, the big-man system aligns with these formal positions; at other times, it operates alongside them. Before contact, no formal village-level mechanisms existed for resolving disputes; conflict was typically addressed through fighting or covert sorcery. Fear of sorcery attack or retaliation remains a strong deterrent and a significant form of social control. Today, minor disputes are addressed in weekly village meetings—institutions introduced by German and Australian administrations—where big-men lead discussions and impose fines. More serious matters are handled by regional courts.

Madak Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Madak rely on subsistence gardening alongside the sale of coconuts and cacao beans. Their staple crops—taro, sweet potatoes, and yams—vary in importance by region. Gardens lie 1–3 miles inland from the coast and also produce bananas, papayas, beans, leafy greens, melons, breadfruit, pineapples, and various nut and fruit trees. Sago, once a famine food, is still occasionally processed. Coastal communities supplement their diets with seasonal fish catches, shellfish, and occasional sea turtles. Pigs and chickens are raised mainly for ceremonial and small-scale special events, and men sometimes hunt feral pigs for minor social occasions. The sale of coconuts and cacao provides a steady but fluctuating cash income, and a handful of villagers run small trade stores offering basic goods such as canned meat, coffee, sugar, and kerosene. [Source: Brenda Johnson Clay, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Work cooperation shifts with context: small groups may share a fenced garden plot, larger groups work together for mortuary feasts, and entire villages join forces for fishing and ceremonial preparations. Work is divided by gender—men clear garden land, build fences, fish, and handle heavy construction, while women plant and tend gardens, gather shellfish, prepare palm-frond roofing, and manage daily cooking. Feast preparations involve men constructing large earth ovens and women cutting and peeling root crops. Both men and women harvest coconuts and collect cacao beans, though men typically transport copra to market in rented trucks driven by men. Before coastal resettlement in the early twentieth century, coastal women exchanged fish with inland women for vegetables. Inter-village trade—both within and beyond language areas—includes red-shell strands, shell bracelets, pigs, rituals and ritual paraphernalia, song-dances, and magic spells.

Settlements: At early contact, the Madak lived in clusters of related hamlets forming a village. Present-day villages range from 50 to 230 people. Some still consist of scattered hamlets, while others—often resettled inland communities—are more centralized. Hamlets vary from 1 to 40 residents living in one to ten nuclear-family houses, usually with a men’s house enclosed by a low stone wall.

Locally Produced Items made from coconut and pandanus leaves and other plant fibers include women’s large carrying baskets, smaller baskets for general use, lime pouches, sitting mats, and rain covers. People also make bamboo slit gongs, large hollow-log gongs, fishing nets, single-outrigger canoes, and log rafts, although canoe- and net-making has disappeared in some areas. Polished-shell bead strands, shell pendants, and arm bracelets are still crafted, but production of white-shell bead strands ended after World War II when a local leader favored red-shell strands from elsewhere.

Land is generally owned by lineages, but actual use is flexible and may involve affines or the children of male lineage or clan members. Offspring can secure permanent rights to their father’s land by making required exchanges at his mortuary feast. When a lineage lacks heirs, individuals with other ties may establish claims by contributing to the final members’ mortuary rites. In some regions, men or women may inherit land through either parent’s paternal kin by offering exchanges at the relative’s mortuary feast. Colonial laws introduced further complexity by requiring cash payments for land leaving clan ownership.

Lesu

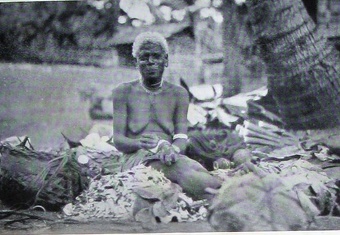

The Lesu live in a long coastal village on the east side of New Ireland. Also known as the Notsi, they have traditionally been slash-and-burn horticulturalists, with taro as their primary staple. Historically, their society centered on a large, independent village composed of matrilineal clans and two exogamous moieties—the Hawk (Telenga) and the Eagle (Kongkong). Kinship, locality, and gender shaped a person’s standing within the community, while the reciprocal relationships between individuals, families, clans, and moieties helped bind the village’s fifteen hamlets into a unified whole. Status distinctions rested on wealth and on possession of magical knowledge, which itself generated wealth through payments for ritual services. Much of what is known about traditional Lesu society comes from research conducted in the late 1920s by Hortense Powdermaker, and it is assumed that the community has since undergone significant Westernization. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Lesu village stretches for roughly 5 kilometers along the northeast coast of New Ireland (2°30' S, 151° E). The landscape is tropical, oriented toward both sea and inland areas, with coconut palms, bamboo, taro gardens, and dense vegetation. “Lesu” refers both to the settlement and to its residents. The Christian-affiliated Joshua Project estimated a population of about 3,800 in the 2020s. Under German control from 1884 to 1915, the Lesu suffered heavy depopulation due to labor recruitment for copra plantations and the spread of diseases, especially tuberculosis. By 1930, only 232 people remained. Language: Lesu villagers speak Notsi, an Austronesian language in the Northern New Ireland Subgroup of the New Ireland–Tolai branch. Today, roughly 1,100 speakers of the Notsi language include the Lesu and their neighbors.

History: Regular European contact began in the late nineteenth century with German and English plantations, followed by missionary activity. Precontact history is unknown, but at the time of European arrival the Lesu were established on the east coast. Intergroup warfare was reportedly common before German rule, typically arising from revenge and resolved through negotiation and compensation; conflict within Lesu hamlets, however, was rare. Incest was considered the most serious violation of social norms, and taboos and avoidance practices were used to prevent it from occurring.

Leadership traditionally rested with the orang—respected senior men from each clan—who formed an informal council that settled village matters. Orang status was not inherited; it depended on age, wealth, personality, magical knowledge, and skill in public speaking. In the past, a warrior chief also existed, but the position disappeared once warfare between villages ceased. Under colonial rule, European administrators appointed a luluai to act as the village’s official representative; he typically consulted the orang regardless of whether he was one himself. Today, village leaders are elected.

New Ireland was visited by Dutch, English, and French explorers and traders in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Germany administered it as a colony from 1884 to 1914, during which time many Lesu were taken as laborers to plantations on and beyond New Ireland, and a coastal road was built with local labor. These changes increased interaction with Europeans and other island communities. From the late nineteenth century onward, Roman Catholic and Methodist missions had a growing influence. In 1914 New Ireland came under Australian administration, was occupied by Japan from 1942 to 1945, and returned to Australian control thereafter. In 1949 it became part of the Trust Territory of New Guinea and has been a province of independent Papua New Guinea since 1975.

Lesu Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 90 percent are Christians, With the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent. Traditional Lesu religion revolved around magic, which was employed to influence nearly every aspect of life. Different forms of magic were recognized—taro, rain, fishing, shark, war, love, black magic (used to kill), and protective magic used to counter black magic. Magic worked through the recitation of specific spells. With the arrival of Christian missionaries, Christian teachings came to coexist alongside traditional beliefs. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Death and Funerals: The Lesu believe that the dead become ghosts who can, if called upon, assist the living, although such spirits do not play a major role in daily religious life. Death is marked by wailing, dancing, feasting, and exchanges of gifts. The deceased is buried in a coffin in the cemetery, after which various taboos and restrictions are observed for several weeks. The higher a person’s status, the more elaborate the funeral rites.

Religious Practitioners: Magicians served as the primary ritual specialists. Both men and women could hold this role, though most were men. They were paid for their services and were often among the wealthiest and most respected people in the village. Each magician typically mastered only one major type of magic, along with some basic medical magic. Those suspected of using black magic could be killed by the victim’s relatives. Illness might be attributed to natural causes or to magic: natural illnesses were treated by healers—men or women—using plant-based remedies, while illnesses believed to result from magic were treated by magicians who attempted to counteract the harmful spell.

Ceremonies: Major life events—birth, boys’ initiation, girls’ first menstruation, marriage, and death—were marked with ceremonies featuring dancing, drumming, and feasting. The most important rituals were the Malanggan rites, held either on their own or, more often, in conjunction with male initiation ceremonies.

Arts: Woodcarving—especially the creation of Malanggan figures—is the most developed artistic tradition. All rituals include dancing by both men and women, with men often appearing in masks and elaborate costumes. More intricate dances are accompanied by drumming and singing. Body decoration, such as hair adornments and facial paint, is also important. The Lesu maintain a rich body of mythology and folktales, many of which are recited or performed during ritual events.

Lesu Family and Kinship

The nuclear family is the core Lesu household unit, consisting of a husband, wife, unmarried daughters, and sons up to about age nine or ten. Boys older than this, unmarried men, and men whose wives are pregnant or nursing live in the men’s house, although their daily activities still revolve around their family household. In polygynous families, each wife and her children typically occupied their own dwelling. Infants are indulgently cared for by both parents, and milestones such as the appearance of a first tooth are marked with feasts. Children participate fully in the daily life of the household and community. From an early age, boys and girls are kept separate; boys form age groups, but girls do not. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

In the past, boys aged eight to eleven underwent an elaborate eight-month initiation rite, preceded by two months of preparation. The ceremony involved seclusion in a specially constructed house, circumcision, feasting, dancing, speeches, and the exchange of wealth. The ritual was always paired with the Malanggan ceremony, during which Malanggan carvings were displayed and then destroyed. Under Roman Catholic influence, the duration of the initiation was shortened and followed by mission instruction. Girls’ first menstruation was marked by feasting and ritual bathing, signifying entry into adulthood and readiness for marriage.

Marriage: Polygyny was traditionally preferred, with many men taking two wives and a few wealthy men having three or four; polyandry occurred but was rare. European influence eventually made monogamy universal. Preferred marriage partners were cross-cousins—especially a mother’s brother’s daughter’s daughter or a father’s sister’s daughter’s daughter—resulting in men often marrying women a generation younger. Divorce was easy and common, and wives always retained custody of the children. Residence after marriage was matrilocal, though marriages within the same hamlet often meant the husband did not have to move. Incest was regarded as the gravest social offense, and numerous taboos helped prevent prohibited interactions.

Adolescent Sex: Hortense Powdermaker wrote in 1933: Children of both sexes may be found on the sandy beach playing at ritual dancing, or imitating adult life in their sexual play, which consists in the boy and girl standing very close together, [their] sexual organs…touching…but not penetrating. It is usually done quite openly in public and the adults smile…and regard it as the natural order of things. This kind of play occurs from the age of about four. Occasionally a boy and a girl will steal away in the bush…which is merely imitating the adult in more detail”. The women practise heel masturbation, a position learned and indulged in from about age six. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, September 2004; [Source: Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Kinship: The two exogamous moieties — the Hawk (Telenga) and the Eagle (Kongkong) — are each composed of several matrilineal clans associated with specific totemic animals and particular land or sea areas. The moieties maintain reciprocal ritual obligations surrounding pregnancy, birth, first menstruation, circumcision, marriage, and death. Clans form the basic economic unit, with members expected to cooperate in major undertakings. Individuals, however, often feel torn between loyalty to their clan and to their household. Status is inherited strictly through the maternal line, whereas property inheritance is more flexible, though items usually pass from a man to his sister’s son.

Kinship Terminology follows the Iroquois (bifurcate-merging) system, which distinguishes parental siblings by both sex and relation to one’s parents. A father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are referred to by terms equivalent to “Father” and “Mother,” while a father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers are labeled with non-parental terms similar to “Aunt” and “Uncle.” Parallel cousins—the children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister—are classified as siblings. Cross-cousins—the children of a brother and a sister—are not considered siblings and are labeled with terms equivalent to “cousin.”

Lesu Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Lesu practice slash-and-burn horticulture, with taro as their staple crop grown in fenced gardens located a kilometer or more inland. Yams are also cultivated, though they play a smaller role than among other groups in New Ireland. Subsistence is supplemented by fishing with nets, traps, and spears, as well as collecting crabs, mussels, and coconuts and hunting wild pigs. At various times, these activities have been supported by income from land sales, plantation labor, and work for colonial administrations. Specialists—such as magicians, healers, dancers, and house builders—are paid for their services in shell money (tsera) or in European currency, with magicians and healers commanding the highest fees. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Work has traditionally been organized by gender. Men clear gardens, plant trees, gather sago, fish, hunt, prepare meat, build and repair houses, and produce masks, canoes, nets, spears, and ornaments. Women plant taro and yams, gather crabs, feed pigs, haul water, maintain the household, and carry most loads. Both sexes make mats and baskets, care for children, and may serve as healers or magicians. Women, however, are excluded from certain types of knowledge, including some myths, forms of magic, and supernatural lore. Magicians, healers, carvers, and net weavers traditionally worked as paid part-time specialists.

Lesu Village in the 1920s was composed of fifteen named hamlets strung along the shoreline. Each hamlet contained two to eight thatched, bamboo-walled houses and a shared cooking area. Larger hamlets also included a men’s house by the shore, a cemetery, and additional cook houses. A mission station was present as well. Personal identity was tied both to membership in Lesu as a whole and to residence in a particular hamlet. Taro gardens lay inland, with Lesu territory extending 8–9 kilometers from the coast.

Trade between individuals and groups followed principles of reciprocity and payment using tsera, a form of shell money consisting of a length of strung flat shells measuring one arm span. Tsera was produced by specialists on Lavongai Island north of New Ireland. Goods were never sold at a profit; items were exchanged at their original value. When Australia assumed control, the shilling replaced tsera as the standard medium of exchange. Baskets were traditionally woven from coconut-palm leaves, fishing nets from plant fibers, and carvings are made in wood and tortoiseshell. By the 1930s, canoe building had already disappeared. The most significant artistic products are the Malanggan carvings used in funerary rituals. These were created by specialists under strict conditions, and in the past only men were permitted to view them.

Land and Inheritance: The Lesu recognize two categories of land. Small parcels of clan land, associated with clan totemic animals, are owned by individual clans. All remaining land and rights to use the sea are held communally by the entire village. Families usually plant gardens on land previously used by their parents, ideally on the wife’s parental land. Ownership of cultivated plants and trees belongs to the gardener—typically the woman who tends the plot. Colonial-era land purchases complicated traditional ownership patterns. Although knowledge and material possessions are ideally inherited through the maternal line, in practice the wishes of the owner or the family often override strict matrilineal rules.

Lak

The Lak people live in Southern new Ireland Province. Also known as the Butam, Guramalum, Laget, Lambel, Pugusch, Siar and Siarra, they are a remote coastal community that practices subsistence farming and fishing, and maintains traditional art forms. They are known for their unique traditions, such as the secret men's cult of the tubuan, and language, Siar-Lak. The Filmmaker Paul Wolffram documented their culture in films like Stori Tumbuna: Ancestors' Tales, which was a collaborative effort to tell the Lak people's stories from their own perspective. [Source: Steven M. Albert, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Lak are a largely coastal group. The term refererd to two groups — an inland group and coastal group — that merged in the early 1900s Today “Lak” is also the official name for the largely Lak-speaking electorate recognized by the New Ireland provincial government. In everyday speech, lak functions like the English “hey” and is used as a common greeting.

The Lak occupy the southeastern tip of New Ireland along a narrow coastal strip rarely more than a quarter mile wide before steep foothills rise inland. The region is extremely remote and has minimal infrastructure—no permanent roads, little electricity, and few public services. Siar village — near 153° E and 4°30' S — sits at the center of the Lak electorate. The Mimias River marks the northern boundary, beyond which lies the Susurunga region. Two offshore islands, Lambom and Lamassa, also host Lak settlements. The area is covered in tropical rainforest and lies just below the equator. The rainy season, taubar (June–September), brought by the southeast monsoon, alternates with labur, when northwest winds dominate and rain may come only once every twenty days—a pattern opposite that of northern New Ireland and the Gazelle Peninsula of New Britain.

Language: Lak, or Siar-Lak, is an Austronesian language known locally as ep warwar anun dat (“our language”). It belongs to the Patpatar–Tolai subgroup of Western Oceanic languages and shows little dialectal variation. Vernacular use remains strong; even so, most adults—except some older women—also speak Tok Pisin fluently. The language has fifteen consonants and seven vowels. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Lak population in the 2020s was 4,200. In the 1980s roughly 1,700 people spoke Lak, a figure shaped by severe depopulation from war and disease in the 1940s–1950s.

History: European ships anchored at Cape Saint George from the eighteenth century onward, but only the 1824 expedition led by Duperrey made direct contact. Crew members Blosseville and Lesson produced the earliest written account of duk-duk, the masked men’s society associated with New Ireland. Before pacification, feuding was endemic. Roaming bands undertook cannibalistic raids. In the late nineteenth century, “blackbirding” drew many New Irelanders into forced labor in Australia and Samoa, though few Lak were taken due to their mobility between coast and interior and their resistance to Europeans. In 1880, the Marquis de Rays attempted to establish “Port Breton” in Lak territory, a disastrous colonization scheme that ended in famine and his imprisonment. Substantial colonial intervention arrived only in 1904, when German authorities launched a punitive expedition against an inland Lak group. By around 1915, most interior communities had resettled on the coast, joining the expanding copra trade. After World War I, administration shifted to British and then Australian control, though outside influence remained limited.

Lak Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 95 percent of Lak are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent. Traditional Lak religion centered on creator beings—two brothers, Swilik and Kampatarai, and their grandmother. Swilik, who shaped the landscape and established the moiety system that guides marriage, has largely been merged with the Christian God as missionization has progressed. Other beliefs focus on lineage ancestors and marsalai, spirits tied to particular places in the landscape. [Source: Steven M. Albert, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Death and Funerals: The recently dead are feared, as they are believed to wander the village and tempt the living toward the spirit world. Prominent individuals may be incorporated into ritual objects, a practice still seen in betel-nut magic but once far more common. Over time, important lineage leaders became lineage ancestors, who are regarded as unpredictable and capable of causing illness or misfortune without clear cause.

Religious Practitioners and Healing: Shamans (iniet) traditionally acted as healers and sorcerers, though few remain today. More common is the tenabuai, a specialist in betel-nut magic. Traditional healing relies on a substantial indigenous pharmacopoeia. Treatment is expensive and often involves extended sessions in which an iniet chants spells over plant materials and blows them onto the patient. Lak people now draw on both traditional and Western medical practices.

Ceremonies: Major mortuary feasts are accompanied by continuous dancing, drumming, and music that can draw hundreds of participants. Big-men sponsor teams of young male dancers who compete in skill and stamina. Men also conduct secret rituals involving tubuan and duk-duk masks, as well as ceremonies using bullroarers (talun).

Ritual objects receive most artistic attention, though Lak designs are generally more restrained than those of many other Melanesian groups. Large, undecorated slit gongs found in many villages were once key ceremonial instruments but are no longer produced. Houses and canoes are typically plain and unornamented. The Lak continue to practice traditional music and dance, including the highly traditional tubuan performances of the men’s secret cult. Their remote location has helped preserve these forms, making Lak culture of particular interest to ethnographers and ethnomusicologists.

Lak Society and Family

Lak society is organized around two moieties: Bongian (sea eagle) and Koroe (fish hawk). Members must marry someone from the opposite moiety. Villages are identified as Bongian or Koroe based on the dominant landowning segment, and these designations shape ritual obligations. For instance, the first time a visitor of the opposite moiety sleeps or dances in the village, he is ceremonially showered with gifts—which must eventually be repaid. [Source: Steven M. Albert, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Lak villages function primarily as food-sharing communities. Households prepare and eat meals separately, but strong social expectations require surplus food to be circulated among neighbors. This principle is most visible in the exchange of komkom, a manioc-based food regularly traded between households. A family may prepare around thirty packets of manioc bread, send half to other households—usually delivered by children—and receive a similar amount in return. Every household is expected to participate, and this continual exchange symbolizes ideal village solidarity. This unity contrasts with tondon, the “work of marriage and death,” which governs the competitive exchanges between lineages, especially during mortuary rituals. During such events, lineage ties become paramount, temporarily overriding village-level solidarity. Outside ritual contexts, however, all village men assemble in the big-man’s men’s house regardless of clan affiliation. Lineages are not localized, and each village contains members of multiple segments.

Lak Households, consisting of a nuclear or extended family, is the basic domestic and economic unit. Each household cooks and gardens independently. Young children are indulged until roughly age five or six, when they typically undergo a crisis moment—being refused something and responding with a prolonged tantrum during which they tear clothing and throw sand. Afterward, the child is expected to take on new responsibilities. Girls begin contributing labor early, sometimes carrying heavy garden produce by age five. Boys take on productive work later and are typically given their first garden plot at around fifteen or sixteen. Full adult responsibility for young men begins with marriage, when they must build a house, establish a garden, perform bride-service for their father-in-law, and begin accumulating the wealth required to advance in the men’s secret society and compete in large-scale feasting.

Marriage follows a single rule : moiety exogamy (marrying outside of one’s group). While certain segments intermarry more frequently, these patterns are not prescriptive. Polygyny—once practiced by big-men—has vanished. A substantial bride-price is required, although marriages are no longer strongly arranged. Postmarital residence varies and depends largely on the influence of each spouse’s segment leader. A man who marries a big-man’s daughter, for example, often resides in the big-man’s village during the early years of marriage. Affinal lineages hold significant stakes in the union and participate in ritual exchanges tied to births and deaths. Pigs may also be exchanged to shame a husband who has struck his wife. Divorce is possible for both spouses; children usually stay with the mother and her lineage.

Kinship: Moiety and clan membership are both matrilineal. Lak clans divide into the two moieties, and some major clans even share names with the moieties, suggesting that other clans may be more recent arrivals. Lineages are defined by their right to build men’s houses and by the ancestors invoked during ritual. Lak kinship follows the Iroquois system, distinguishing same-sex and cross-sex parental siblings. Father’s brothers and mother’s sisters are called “father” and “mother,” while father’s sisters and mother’s brothers are “aunt” and “uncle.” Parallel cousins are classified as siblings, while cross cousins are categorized as cousins and potential marriage partners.

Political Leadership follows a classic coastal Melanesian big-man system. A kamgoi (big-man) gains status by working hard to accumulate pigs and wealth, enabling him to take a central role in competitive feasts and to purchase rights over important ritual objects, including tubuan and duk-duk masks. A successful big-man persuades others to contribute labor, expanding his influence and sometimes incorporating whole lineages into his own segment. He sponsors mortuary feasts for all segment members and may control the group’s shell-money stock.

Tubuan Justice: Ritual sanctions are traditionally enforced by the tubuan. Masked figures appear at night to punish offenders—historically even killing them with a special axe (firam). Civil disputes today are handled by village courts, where an elected representative relies on public opinion to resolve matters such as bride-price disagreements, sorcery accusations, and minor etiquette violations. Cases involving violence may be referred to a provincial officer.

Lak Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Lak economy is centered on subsistence gardening and fishing, supplemented by pig raising. Pigs provide the main source of protein and are most often slaughtered during mortuary ceremonies. Households also produce coconuts and cocoa as cash crops, though earnings are modest and typically used to cover school fees. The household is the primary unit of both production and consumption, but villages are tightly linked through extensive food-sharing networks. In the northern district, taro is the staple crop; in the south, manioc and sweet potatoes dominate. Each household maintains two swidden gardens at the same time—one near the beach for manioc and pineapples, and another inland with a wider range of crops such as taro, yams, sweet potatoes, melons, sugarcane, bananas, leafy greens, and recently introduced vegetables. Tubers are planted using digging sticks, and gardens are fenced and trapped to keep out both wild and domestic pigs.

Manioc is grated, mixed with coconut oil, and baked in earth ovens to make gem or komkom, a type of bread exchanged between households several times a week along with cooked dishes. Families also gather many varieties of wild fruits and nuts. Protein comes mainly from pigs, especially village-raised animals that roam freely despite periodic efforts to pen them. Wild pigs and cuscus are hunted with spears; reefs supply abundant shellfish; and Lak men are skilled at catching large sea turtles. Turtle eggs, collected from the beaches, are highly valued. Coconut and cocoa harvesting provides hard currency, but as of 1986 a highly industrious household earned no more than around US$400 annually, limiting access to high-school education.

Work: has traditionally included the production of canoes, plaited mats and baskets, wooden bowls, and pig traps. Men and women clear land, plant, harvest, and string nassa shells for traditional currency (sar). Garden maintenance remains largely women’s work, while men control the magical practices associated with crop fertility and pig growth. Hunting and major rituals are male domains, and men alone fish. Women perform all domestic chores. Intervillage trade centers primarily on pigs, which are transported alive between lineage leaders preparing for mortuary feasts. Before European contact, the Lak participated in a wider interisland trade network linking southern New Ireland with Nissan and Anir, exchanging foodstuffs and ritual objects.

Villages are small and dispersed. A large village has ten to fifteen houses—no more than seventy to eighty people—and is typically linked to nearby hamlets of one to three houses each. A notable exception is densely populated Lambom Island, where limited land and water have altered this pattern. Men build houses collectively, but each dwelling is occupied by a single nuclear family. At the edge of every settlement is a triun, an area forbidden to women and children and used for men’s society activities. Nearby, or sometimes within the village, stands the men’s house (pal), where bachelors and men whose daughters have reached puberty sleep. Villages lie along the coast in cleared areas surrounded by coconut groves and betel palms, with gardens located further inland.

Garden Land is considered inalienable and belongs to matrilineal segments, under the stewardship of each segment’s big-man (kamgoi). All cultivated land within a village area is owned by the dominant segment, though the kamgoi allows any resident to plant there. His role does not extend to controlling garden production. Although landownership is theoretically fixed, tenure does shift over time. Segments may move between larger matrilineal units, or—if a big-man can rally enough support—landowning segments may sell land to individuals for coconut or cocoa cultivation. Rent or lease arrangements also occur. Inheritance is predominantly matrilineal for the two most important assets—land and ritual objects. However, fathers often give money to their sons so they can purchase land or gain access to rituals, creating a subtle, secondary form of patrilineal transmission. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, New Ireland Tourism

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025