Home | Category: Island Ethnic Groups

EAST NEW BRITAIN PROVINCE

East New Britain is situated on the northeastern part of New Britain Island and includes the Duke of York Islands. The provincial capital is Kokopo, established after the former capital, Rabaul, was devastated by the 1994 volcanic eruptions of Mount Tavurvur and Mount Vulcan. The province covers 15,816 square kilometers, with a population that grew from 220,133 in 2000 to 328,369 in 2011. It shares a land border with West New Britain and maritime boundaries with New Ireland. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels, Wikipedia ]

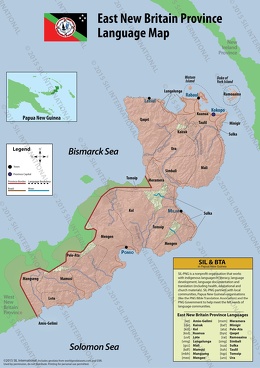

East New Britain is strikingly different from mainland Papua New Guinea. It has a Caribbean-like charm, with swaying palm-lined beaches and ocean breezes. It is linguistically diverse, with sixteen Austronesian languages spoken in the province. Kuanua, spoken by the Tolai of the Gazelle Peninsula, is the most widely used. Several Papuan languages are also spoken, including Baining, Taulil, Ata, Kol, Makolkol, and Sulka. The province has a dual economy, combining subsistence agriculture with a growing cash economy. Cocoa and copra are the main export crops, and tourism—centered on natural landscapes, World War II sites, and volcanic features—continues to expand.

Rabaul, once known as the “Pearl of the Pacific,” sits on Simpson Bay, a deep-water harbor on the Gazelle Peninsula. Flanked by Mount Tavurvur and Mount Vulcan, it has been repeatedly shaped by volcanic activity. The 1994 eruption buried much of the town under ash, destroying about 80 percent of its buildings. A major earlier eruption in 1937 killed more than 500 people and virtually destroyed Rabaul. . Today, Rabaul remains a center for tourism — offering views of Tavurvur, hot springs along Blanche Bay, a volcano observatory, and numerous World War II relics — despite having an eerily abandoned feel. The Rabaul Hotel is one of the few major buildings that survived the twin eruptions.

The Duke of York Islands comprise 13 islands situated in St. George’s Channel between New Britain and New Ireland. They form part of the Bismarck Archipelago and were named in 1767 by British naval officer Philip Carteret in honor of Prince Edward, son of Frederick, Prince of Wales.

RELATED ARTICLES:

WEST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — NAKANAI, AROWE — AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MASKS AND ART OF NEW BRITAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

NEW IRELAND ETHNIC GROUPS — MADAK, LESU, AND LAK— AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM NEW IRELAND: MALAGAN, FUNERARY FIGURES AND DRUMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOUGAINVILLE ISLANDERS — SIWAI, TINPUTZ, NAGOVISI — AND THEIR HISTORY, SOCIETIES AND CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NASIOI OF BOUGAINVILLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

NISSAN ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, BIG MEN POLITICS, ECONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDER CULTURE: CUSTOMS, MATRILINEAL SOCIETY, SEX AND YAMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE TROBRIAND ISLANDS AND MASSIM REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ISLANDERS OF NORTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA ON MANAM, WOGEO AND MANUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA ISLANDERS OF MASSIM, MILNE BAY AND DOBU, ROSSEL AND GOODENOUGH ISLANDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

History of East New Britain

East New Britain province was among the first areas of Papua New Guinea to be settled and developed by Europeans. During German occupation (1884–1919), Rabaul’s harbor was developed, and in 1905 the town became the capital of German New Guinea. In 1919, at the start of World War I, Australian forces captured the island. Following Germany’s defeat, East New Britain was administered by Australia under a League of Nations mandate from 1920. By 1937, Rabaul had evolved into a pleasant colonial town, though it was racially segregated and overwhelmingly Eurocentric, reflecting the British loyalties of its Australian administrators. That year, volcanic eruptions devastated the town, temporarily halting its role as a regional center. [Source: Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

During World War II, Rabaul was the first Australian territory attacked by Japan. On January 4, 1942, the town endured heavy bombing and was soon occupied. Its strategic harbor made it a major Japanese military and naval base in the South Pacific, intended to isolate Australia from Southeast Asia and the Americas. The Japanese dug extensive tunnels as shelters from Allied attacks—many of which remain today. Following Japan’s surrender in August 1945, the island returned to Australian administration.

After the war, Rabaul remained the primary city and port of the Bismarck Archipelago, but it never regained its status as provincial capital. Kokopo became the administrative center, while Port Moresby served as the capital for the territories of East New Britain and Papua New Guinea.

Baining People

The Baining take their name from the mountains of the Gazelle Peninsula, their ancestral homeland. Although considered the peninsula’s earliest inhabitants, they were later pushed into the interior by the Tolai, migrants from New Ireland. This retreat earned them the Tolai nickname “bush people.” About an hour’s drive from Kokopo lies Gaulim village, one of the main Baining communities. [Source: Wikipedia, Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

Linguistically, the Baining are distinct from both the Tolai and the Pomio peoples. Their language family includes six languages—Kairak, Makolkol (now extinct), Mali, Qaqet, Simbali, and Ura. Colonial administrators resettled them into permanent villages, interrupting their former semi-nomadic pattern, though their agricultural life remained largely unchanged. They practice slash-and-burn horticulture, with taro as the traditional staple. After a taro blight in 1957, most local varieties were replaced by Singap or Concon taro. The Baining resisted colonial attempts to introduce bananas, beans, and other staples, though they now grow various vegetables alongside taro. Gardens are often located far from the village.

Ethnographers have noted that Baining society—like that of Samoa—places little emphasis on traits celebrated in the West, such as individualism or overt emotional expression. Their culture is strongly work-oriented and geared toward the welfare of the community rather than the individual. This has fueled a long-standing rumor that Baining children are discouraged from play or punished for “unproductive” behavior. Villagers firmly deny this. Such misconceptions helped advance the outdated stereotype that the Baining are “primitive” or lacking in religion or art—a view contradicted by the richness of their ceremonial life.

Baining Fire Dance

The Baining are renowned for their spectacular Fire Dance. Traditionally performed to mark major events—such as a birth, the start of a harvest, or the honoring of the dead—the ceremony originated in the northern region (where it was called Atut) before spreading to central and southern Baining communities.

During the ritual, “Spirit Men” wearing elaborate bark-cloth masks and leaf adornments dance around—and directly through—the flames of a large bonfire. Moving in rhythm with the intensifying music, they stamp barefoot across burning logs, sending showers of embers into the air like a volcanic eruption. The dance is performed at night and often marks a young man’s initiation into adulthood.

The towering masks, known as Kavat, are several times larger than a dancer’s head yet remarkably light. Made from pounded white bark cloth (tapa) stretched over bamboo and reed armatures, each mask is created for a single performance and then discarded or destroyed. Mask-making is an essential part of male initiation, and the most skilled makers craft those used for major ceremonies.

The masks embody forest spirits—animals and plants—typically featuring wide, startled eyes and a broad, duck-like bill. Painted with red and black pigments derived from tree sap and berries, they include a large rounded throat piece and a bark-cloth phallocrypt. Designs use black to create bold negative patterns on the white bark cloth, accented with red outlines.

In Baining symbolism, red represents masculinity and connects to fire, blood, hunting, warfare, and ritual sacrifice. Dancers traditionally “activated” the masks by spitting blood onto them; in earlier times, this was done by piercing the tongue. According to legend, the performers are momentarily possessed by Masaray—anthropomorphic forest spirits who heighten the dancer’s strength and masculinity. Color symbolism in East New Britain differs markedly from that of the Highlands. Here, black denotes femininity and is linked to hearth ash, fertile soil, and the damp forest places where potent spirits dwell. White, the color of the bark cloth, signifies the supernatural.

Unlike most Papuans, the Baining people have a deep aversion to the forest. They view it as a wild, dangerous, and chaotic place that must be tamed. In the Fire Dance, masked dancers represent forest spirits, and a male orchestra represents civilization. Symbolically, the dancers, or spirits, wreak havoc throughout the night and are then "chased" back into the forest at sunrise by the orchestra, or civilized man. The Fire Dance is a men-only event that is not traditionally attended or watched by Baining women or children. In fact, women and girls are forbidden from touching the masks. However, the women perform a night ritual to "cool" the main ceremonial grounds before the Fire Dance.

Baining Fire Dance Performance

Describing a Baining fire dance performance she witnessed, Latonia Gray wrote in Soul-O-Travels: Following a bumpy, dirt road just after sunset, we arrived at a clearing nestled in the mountains of Gaulim. Upon disembarking our van, our noses were assaulted by the smell of burning wood and grasses. The crackle and pop of the flames as they engulfed the firewood added to the anticipation of what we were about to see. [Source:Latonia Gray, Soul-O-Travels]

As the flames grew higher, a group of village elders seated on the edge of the dance area acted as the “orchestra”. Much like a formal concert, they signaled the start of the performance. They began a low chant accented by a beat made by striking bamboo poles against logs. Our guide, Mark, encouraged us not to get so mesmerized by the dance that we missed the beauty of the music. He was absolutely correct – it was hard to believe the melodies we were hearing were made with just voices and materials taken from the forest.

Suddenly, a shamanic-looking man in a conical hat, called “Lingenka”, appeared at the edge of the clearing. He had an almost Seussical look to him with his conical hat topped with a heart and a spire. The spire measured over a meter high and was adorned with feathers resembling the plumage of the bird of paradise.

His visage was carefully hidden behind a fringe of pandanus leaves arranged around the inside brim of the hat. Black paint covered his torso and upper thighs, while his arms and legs were painted white. His calves were decorated with a shaft of leaves secured just below his knees and at the ankles. Across his shoulders was a type of cape fashioned out of leaves that swayed and twirled as he danced frantically leading the other “spirits” in the performance.

One by one each performer entered the clearing and performed his dance for one complete verse of the song chanted by the Elders. After performing, they retreated to the shadows at the edge of the fire circle. They they danced in place with the leader until all the performers had completed their round. Once they had all completed their introductory dances, the real fun began as they all danced and jumped around the fire to the frenetic beat of the bamboo poles.

The identities of the “Spirit Men” are carefully guarded. We witnessed a few men being suddenly whisked away into the shadows. When I inquired what happened they explained that the man’s identity had been compromised. Translation: either he had a wardrobe malfunction or possibly had been injured kicking the fire. As the men jumped and danced, they frequently kicked at the embers and smoldering wood sending showers of sparks flying into the air and singeing parts of their costumes. What’s even more impressive is they danced around and into the fire with their bare feet. While the dance alone was mesmerizing, our guide told us not to neglect paying attention to the sounds of the voices and the music of the bamboo poles. It truly was exceptional and unlike anything I had ever witnessed.

Tolai

Tubuans dancing at a mortuary ceremony, Gunanur, September 2003 Open Edition Journals

The Tolai are an indigenous people of the Gazelle Peninsula and the Duke of York Islands in Papua New Guinea. Renowned for their matrilineal social structure, elaborate ceremonial life, and distinctive shell-money system, they share close ethnic ties with peoples of nearby New Ireland, including groups such as the Tanga. They are widely believed to have migrated to the Gazelle Peninsula in relatively recent times, pushing the earlier Baining inhabitants into the mountains. Today the Tolai form one of the region’s larger ethnic groups, and while most identify as Christian, many traditional beliefs and practices remain integral to community life. [Source: A. L. Epstein, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia; Google AI]

The term Tolai is relatively modern. Historically, the people living within roughly 32 kilometers (20 miles) of Rabaul had no single collective name. Catholic missionaries once used Gunantuna—meaning “the true land” or “the proper land”—though this has since fallen out of use. The name Tolai, believed to have originated from a friendly local greeting, dates from the 1930s.

Geographically, the Gazelle Peninsula—at 151°30 E and 4°30 S—was long separated from the rest of New Britain by the Baining Mountains. It is one of Papua New Guinea’s most tectonically active regions, dominated by the volcanic craters surrounding Rabaul Harbour. Centuries of ash deposits have created unusually fertile soils. The climate features two main seasons: the taubar, the period of Southeast trade winds (May–October), and the labur, the northwest monsoon and rainy season.

According to the Joshua Project, the Tolai population in the 2020s was about 167,000. At the time of early colonial contact in the late 19th century, their numbers were estimated at around 30,000, making the region one of the most densely populated parts of Melanesia, with more than 100 people per square kilometer. Population growth accelerated dramatically through the late 20th and early 21st centuries—reaching approximately 120,000 by the late 1990s—and remains high today. With an area of roughly 910 square kilometers, the resulting density contributes to a range of social pressures.

Language: Most Tolai speak Kuanua—also called tinata tuna, meaning “the true word” or “proper word.” Smaller communities speak Lungalunga and Bilur, each with about 2,000 speakers. Kuanua is an Austronesian language closely related to those of southern New Ireland rather than to other languages of New Britain. While local dialects once varied widely, missionary activity helped standardize the language and extend its use throughout the Duke of York Islands, New Ireland, and other parts of the region.

Tolai History

The Tolai migrated to the Gazelle Peninsula from neighboring New Ireland over several centuries, gradually displacing the indigenous Baining people, who retreated westward into the mountains. The region’s volatile geology has long shaped Tolai life; major eruptions in 1937 and 1994 devastated settlements and forced the relocation of thousands, disrupting kinship networks and traditional social structures. [Source: A. L. Epstein, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Traders, missionaries, and other outsiders began arriving in the 1870s. Methodist ministers and teachers from Fiji introduced Christianity to the islands region in 1875. Three years later, in 1878, conflict erupted when several Tolai clans killed and consumed four Fijian missionaries. In response, their leader, the English missionary George Brown, directed—and personally joined—a punitive expedition that resulted in the deaths of a number of Tolai people and the burning of several villages. In 2007, more than a century later, descendants of the Tolai involved in the incident formally apologized to Fiji’s High Commissioner, Ratu Isoa Tikoca, who accepted the gesture. At the ceremony, Papua New Guinea’s Governor-General Paulias Matane acknowledged the influential role of early Fijian missionaries in spreading Christianity throughout the islands.

In 1884 Germany annexed the Gazelle Peninsula as part of its colonial territory in New Guinea. With fertile volcanic soils, favorable climate, and the deep natural harbor of Blanche Bay, the area became a hub of plantation agriculture. By 1914 the Tolai had undergone profound social and economic changes. Although much of their land had been taken for plantations, many Tolai were also benefiting from the copra trade and increasing access to missionary education, which opened pathways to new occupations.

After Germany’s defeat in World War I, administration of the region passed to Australia under a League of Nations mandate. The interwar years brought little development, though by the late 1930s some recovery was underway and living conditions were improving for Tolai communities near Rabaul.

World War II brought new hardships. The Gazelle Peninsula became a major Japanese garrison, and as Allied naval victories severed Japanese supply lines, local conditions deteriorated sharply. Many Tolai died from maltreatment, starvation, and lack of medical care. Following the war, Australian rule resumed, this time with significant investment in local government, education, health services, and economic development. Despite rising economic opportunities in the 1960s, social tensions also increased, ultimately giving rise to the Mataungan movement—a powerful local political force that played a key role in the push for self-government and, eventually, Papua New Guinea’s independence.

Tabu distributed at a mortuary ceremony, Gunanba, October 2003 Open Edition Journals

Prominent Tolais

Vin ToBaining (one of the first six elected indigenous members of the colonial-era Legislative Council of Papua and New Guinea)

Sir Rabbie Namaliu (4th Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea)

Sir Ronald ToVue (Premier of East New Britain (1981-1989))

Sir Paulias Matane (8th Governor General of Papua New Guinea and 1st Ambassador of Papua New Guinea to USA)

Grand Chief Damien Kereku (former Regional Member of East New Britain)

Sir Henry Torobert (1st Governor of the Bank of Papua New Guinea)

Sir John Kaputin (Secretary General of ACP-EU — 2005 to 2010)

George Telek (King of Tolai Rock)

Anslom Nakikus (Reggae Artist)

Tolai Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 99 percent of Tolai are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 10 to 50 percent. Most Tolais are Roman Catholic or members of the United Church. However, traditional beliefs persist through rituals and the veneration of the female spirits of the Tubuans with secret ceremonies performed by initiates of the Duk-Duk society as well as the belief in sorcery to either gain someone's love or to punish an enemy. [Source: Wikipedia; Joshua Project]

Tolai cosmology recognizes a wide range of spirits collectively known as tabaran. “Spirits of the air” are considered benevolent and are invoked for inspiration in composing songs, designing ceremonial costumes, or creating choreography for major dances. Other spirits—those that inhabit the bush and often take grotesque forms—are viewed as dangerous and are deeply feared. At the core of Tolai religious life is the spirit of the tubuan. The tubuan is “raised” to dance at various festivals, or balaguan, but its most important appearance occurs during the matamatam, a major rite honoring all deceased members of the clan. During this ceremony, the masked figures of both the tubuan and dukduk—the central spirit of the male secret society—emerge. [Source: A. L. Epstein, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Death and Funerals: In earlier times, coils of tambu were cut and distributed to ensure that the deceased could enter the “Abode of the Spirits.” To die without having tambu cut was a disgrace for one’s lineage and condemned the spirit to eternal misery in the land of IaKupia. Although more than a century of Christianity has diminished much of the traditional ideology surrounding death, tambu retains its deep ritual and symbolic power, continuing to link present generations with their ancestors.

Religious Specialists known as melem are still required to “raise” the tubuan. While much traditional knowledge relating to garden and fishing magic has largely disappeared and is rarely practiced, belief in sorcery remains widespread. Individuals with knowledge of the medicinal properties of plants may be consulted as healers for specific ailments. However, healing is another area in which indigenous culture has been greatly eroded. Nowadays, the Tolai regularly consult Western-trained practitioners, some of whom are Tolai themselves. ~

The Duk-Duk and Tubuan societies continue to function as influential male secret societies responsible for key rituals and initiations. Their presence is most visible in Tolai ceremonial life, which remains vibrant and expressive despite generations of missionary influence. Music, dance, and oral storytelling are central to these events and are prominently featured at public celebrations such as the National Mask & Warwagira Festival, where the iconic Duk-Duk costume is often showcased.

Ceremonies are occasions of great pageantry, and much Tolai artistry is invested in these events. Dancers wear colorful, custom-designed costumes and carry carved, ornamented staves prepared for the occasion. Artists, whether carvers or composers, enjoy very high prestige. Despite early missionary efforts to suppress traditional ceremonies, the balaguan and matamatam are still performed much as they were a century ago, as noted by early observer Richard Parkinson. Today, almost all Tolai identify strongly with Christianity, and church activities are deeply woven into village life. Yet traditional forms of celebration remain integral: ceremonies are held not only for deaths but also for milestones such as the completion of a new house, the installation of a water tank, or even a birthday—events still marked through the exchange of tambu, the Tolai shell money.

See Separate Article: MASKS AND ART OF NEW BRITAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

Tolai Society and Family

Tolai society is organized around matrilineal clans (vunatarai), with lineage traced through the female line. The Tolai are divided into two moieties, a dual structure that historically governed marriage and regulated social life. Everyday interaction is highly local, centered on the hamlet or on larger neighborhood clusters within a village. Yet each hamlet maintains friendly, enduring ties with others across the region through clan affiliation, intermarriage, trade, and shared ceremonial obligations. Modern transportation and an extensive road network have strengthened rather than weakened these traditional links. [Source: A. L. Epstein, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The basic domestic and economic unit is the household, typically composed of a nuclear family. Childrearing emphasizes obedience, and discipline may be enforced in various ways. Education is a major parental concern, and many Tolai children study away from home—often resulting in limited exposure to local customs. In earlier times, boys and likely girls underwent initiation rites at puberty, receiving moral and sexual instruction in special houses; initiation was required before engaging in sexual relations. Inheritance remains matrilineal, though there is growing pressure today to recognize the claims of a man’s wife and children to personal property and income.

Marriage: Polygyny once played a significant role in Tolai marriage but is now rarely practiced. A proper marriage traditionally required a bride-price in tambu (shell money), a custom that continues today. Although postmarital residence is ideally virilocal—living with or near the husband’s family—there is flexibility, and some marriages are uxorilocal or follow other arrangements. Legally, divorce in customary marriage is not difficult, but in practice marriages have tended to be stable, though change is becoming more evident.

Kinship: Every person belongs to one of two matrimoieties, which strictly prohibit sexual relations within the same group—once considered a serious offense punishable by death. Individuals also inherit membership in their mother’s clan, a dispersed unit linked to one or more places of origin from which members have branched out over time. These clan networks span multiple communities and continue to form the foundation for cooperation in economic matters and, especially, ceremonial life. Tolai kinship terms follow the Iroquois (bifurcate merging) pattern. A father’s brothers and a mother’s sisters are referred to using the same terms as “Father” and “Mother,” while a father’s sisters and a mother’s brothers use distinct terms comparable to “Aunt” and “Uncle.” Parallel cousins (children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister) are classified as siblings, whereas cross cousins (children of a brother and sister) are distinguished as cousins.

Political Organization traditionally lacked centralized authority or hereditary leadership. Instead, leadership fell to influential big-men whose status depended on their ability to accumulate and mobilize wealth—especially tambu—used to sponsor large ceremonies or, today, business ventures. Since the 1950s, Tolai communities have been formally integrated into local government councils that still reflect earlier territorial divisions.Big-men historically exercised significant authority through their control of tambu. The tubuan spirit, central to the male cult, also functioned as an agent of social regulation. Local disputes were settled in village assemblies or varkurai, where fines or compensation were paid in tambu. Intergroup conflicts were similarly resolved through tambu payments. In recent decades, these traditional moots have been replaced by village courts, while land disputes are now handled by appointed land mediators.

Tolai Life

Villages of about 300 people form the basic settlement Tolai unit, each composed of small hamlets made up of a few households. In remote rural areas houses are built of traditional materials, while those near Rabaul may be substantial two-story structures with copper roofs, louvered glass windows, and private water tanks. Many villages have their own churches and schools—often impressive buildings planned and constructed by the residents themselves. [Source: A. L. Epstein, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Work patterns vary by task, but cooperation among men—for example in housebuilding or launching a fish trap—is typically rewarded with tabu or a small feast. A clear division of labor exists along gender lines: men undertake heavy work such as clearing new gardens, while women handle weeding and harvesting. Husbands and wives often work together in their plots. Only men fish, and fishing beaches are taboo to women; however, women quickly gather when a catch is brought ashore to buy fish for cooking and resale at the market. Women also accompany men to collect megapode eggs, selling snacks to the hunters and later marketing the eggs.

Coconut Palms are central to daily life: their fruit provides food, drink, and cooking ingredients; husks supply fuel; and fronds are used for shelter and weaving. After European traders arrived, coconuts quickly became a major cash crop through the production of copra. Cocoa, introduced in the 1950s, soon rivaled copra as a primary source of income.

Land is theoretically owned in perpetuity by the vunatarai, a dispersed matrilineal clan. In practice, effective control rests with the local matrilineage segment, also called vunatarai, whose leader allocates use rights to members. Although land is meant to stay within the matrilineage, a man may grant a portion of his matrilineal land to a son as part of his paternal obligations. This land should revert to the matrilineage upon the father’s death, but over time such arrangements are often forgotten, leading to frequent disputes.

Tolai Agriculture and Economic Activity

Tolai economic life traditionally centers on a shell-money system known as tabu or diwarra, made from strings of nassa shells threaded onto canes. This currency serves both ceremonial and practical purposes and continues to function alongside the national currency (kina and toea). Tabu is essential in major social transactions—such as bride-price payments, funeral exchanges, and initiation fees—and is also accepted as legal tender in markets. Large coiled bundles of tabu, called loloi, are displayed as symbols of wealth and prestige. [Source: Google AI; Wikipedia]

Swidden agriculture forms the subsistence base, supported by rich volcanic soils. Inland communities grow taro, yams, sweet potatoes, and an impressive range of bananas—said to number around seventy varieties. Along the coast, people supplement gardening with seasonal seine and basket fishing. A prized delicacy comes from megapode eggs, which the bush turkey deposits in the warm volcanic soils near crater bases. [Source: A. L. Epstein, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The household is the primary unit of production and consumption. Tolai craft production includes canoes and the large basketlike fish traps known as wup, as well as finely made mats and baskets woven from coconut and pandanus leaves. Specially carved and painted staves and masks are created for particular dances and ceremonies.

In addition to local production, Tolai have long participated in wage labor. After World War II, they formed an occupational elite—working as teachers, clerks, carpenters, and skilled tradespeople throughout the country. Today many Tolai hold university degrees and serve as professionals—doctors, lawyers, architects—and as senior administrators in Port Moresby and other urban centers.

Trade: Although small, the Gazelle Peninsula contains marked ecological variation, fostering localized production and a long-standing system of internal trade. Before European contact, goods moved through networks of intermediaries linking inland and coastal communities. The economy was highly monetized, with most exchanges conducted in tabu. Today the major markets at Rabaul and Kokopo continue this tradition. Rabaul’s daily market offers a wide range of produce to a diverse clientele; while most sales are now made in cash, tabu remains recognized as legal tender.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025