Home | Category: Island Ethnic Groups

BOUGAINVILLE ISLAND

Bougainville Island is the main island of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville in Papua New Guinea. The largest island in the Solomon Islands archipelago, it covers about 9,300 square kilometers (3,600 square miles). Its highest point is Mount Balbi (2,715 meters, 8,907 feet). To the north lies the much smaller Buka Island (roughly 500 square kilometers, 190 square miles), separated from Bougainville by the narrow Buka Strait, a 400–500 meters (1,300–1,600 feet) channel crossed by regular ferries. The main northern airstrip is in Buka town. Buka’s northern outcropping sits about 175 kilometers (109 miles) from New Ireland, the closest major island in Papua New Guinea. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bougainville is an autonomous region rather than a province of Papua New Guinea. The estimated population of the region in 2011 was 250,000. Bougainville was once the core of the German-administered North Solomons, whereas most of the broader archipelago now forms the independent state of Solomon Islands. To its immediate south lie the Shortland Islands, barely 9 kilometers (5.6 miles) away and about 30 kilometers (19 miles) west of Choiseul.

Bougainville island is heavily forested and forms part of the Solomon Islands rainforests ecoregion. Bougainville and Buka were once a single landmass, now split by the deep Buka Strait. Several active or dormant volcanoes rise to around 2,400 meters (7,900 feet). Bagana Volcano (1,750 meters / 5,740 feet) remains highly active, emitting visible gas plumes. In 2013, a magnitude 6.4 earthquake struck 57 kilometers (35 miles) south of Panguna. Bougainville has a tropical rainforest climate, with February being the driest month.

Bougainville hosts one of the world’s largest copper deposits. The Panguna mine, opened in 1972, contains an estimated one billion tonnes of copper ore and 12 million ounces of gold. Operations ceased amid the uprising against the Australian-run, Rio Tinto–owned project, which had caused severe environmental damage from heavy metals. More recently, population pressures and deforestation have disrupted local river systems. The UN Environment Programme has offered assistance with cleanup efforts and the possibility of reopening the mine under stricter environmental controls.

RELATED ARTICLES:

NASIOI OF BOUGAINVILLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

NISSAN ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NEW IRELAND ETHNIC GROUPS — MADAK, LESU, AND LAK— AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM NEW IRELAND: MALAGAN, FUNERARY FIGURES AND DRUMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

EAST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — THE BAINING AND TOLAI — AND THEIR CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES AND DANCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WEST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — NAKANAI, AROWE — AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MASKS AND ART OF NEW BRITAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, BIG MEN POLITICS, ECONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDER CULTURE: CUSTOMS, MATRILINEAL SOCIETY, SEX AND YAMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE TROBRIAND ISLANDS AND MASSIM REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

ISLANDERS OF NORTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA ON MANAM, WOGEO AND MANUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA ISLANDERS OF MASSIM, MILNE BAY AND DOBU, ROSSEL AND GOODENOUGH ISLANDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Bougainville History

During the Last Ice Age, Bougainville, Buka, and the Nggela Islands formed a single landmass known as “Greater Bougainville.” The oldest evidence of human settlement is at Kilu Cave on Buka, dating from 26,700–18,100 B.C.. The earliest inhabitants were Melanesians related to modern Papuans and Indigenous Australians. Around the 2nd millennium B.C., Austronesian settlers arrived with domesticated animals and obsidian tools. [Source: Wikipedia]

European contact began in 1768 when French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville sighted and named the island. British and American whaling ships visited throughout the 19th century. Germany annexed the island in 1899, and Christian missions followed in 1902. Australia took over during World War I, administering Bougainville as part of the Territory of New Guinea from 1920. During World War II, Japan occupied the island in 1942, prompting the Allied Bougainville campaign in 1943. Japanese forces remained isolated on the island until 1945. Notably, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was killed over Bougainville in 1943 when his aircraft was shot down.

In 1949, Bougainville became part of the UN Trust Territory of Papua and New Guinea under Australian control. When Papua New Guinea prepared for independence in 1975, Bougainville briefly declared itself the Republic of the North Solomons, but was reintegrated into PNG. From 1988 to 1998, the Bougainville Civil War resulted in more than 15,000 deaths. New Zealand–brokered negotiations in 1997 led to autonomy and the deployment of an international Peace Monitoring Group. A 2001 peace agreement guaranteed a future referendum.

The referendum was held 23 November–7 December 2019, with 98.31 percent of voters choosing full independence. The result is non-binding, and final status depends on negotiations with the PNG government. Bougainvillean leaders have expressed hopes for independence by 2027, though PNG has not formally committed.

Bougainville People and Linguistic Groups

The population of Bougainville is predominantly Melanesian, descended from ancient Australo-Melanesian settlers and later Austronesian migrants who arrived more than 3,000 years ago. Small Polynesian communities also live on outlying atolls, though they form only a tiny portion of the population. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bougainville remains highly diverse linguistically and culturally. Despite long-term mixing, many distinct languages and group identities persist across coastal, highland, and island regions. Genetic studies have also highlighted the distinctiveness of Bougainvilleans, including unusually high frequencies of a particular Denisovan-derived gene, the result of ancient interbreeding events. Most Bougainvilleans are Christian, with roughly 75–80 percent Roman Catholic and the remainder belonging mainly to the United Church and the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

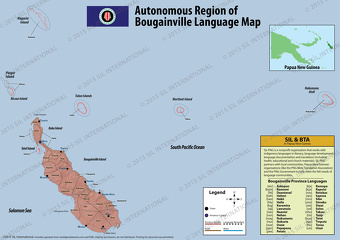

Bougainville’s linguistic diversity is exceptional, with languages belonging to three major families: 1) Austronesian languages – spoken primarily in northern Bougainville, Buka Island, and various coastal areas; 2) North Bougainville languages (non-Austronesian) and 3) South Bougainville languages (non-Austronesian)

The most widely used Austronesian language is Halia, spoken on Buka and the Selau Peninsula. Other northern Austronesian languages include Nehan, Petats, Solos, Saposa (Taiof), Hahon, and Tinputz. Bannoni and Torau are Austronesian languages of the central and southern coasts. On Takuu Atoll, residents speak Takuu, a Polynesian language. Non-Austronesian languages on the main island include Rotokas—famous for its extremely small phoneme inventory—along with Eivo, Terei, Keriaka, Naasioi (Kieta), Nagovisi, Siwai (Motuna), Baitsi, and Uisai. Most people use Tok Pisin as a lingua franca, while English and Tok Pisin serve as the main languages of administration and government.

Siwai

The Siwai occupy the center of the Buin Plain of southern Bougainville — at 7°S and 155° W — which is in the humid tropical lowlands. Almost all of the population lives below 200 meters above sea level. Some Siwais now live in urban areas in other parts of Papua New Guinea. The word "Siuai" originally applied to a cape on the southern coast of Bougainville, but it later came to identify a wider area of the coast, its hinterland, and the people who lived there. The Uisia are similar to and live near the Siwai. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Uisai population in the 2020s was 6,700. In prewar years, the Siwai population was around 4,500; by the mid-1970s it had grown to about 9,000 and by the late 1980s was probably about 13,000. ~

Language: The Siwai (Motuna) language is a non-Austronesian (Papuan) language closely related to other inland South Bougainville languages such as Buin, Nagovisi, and Nasioi. Within the Siwai region itself, only minor dialect differences occur.

History: Linguistic, archaeological, and oral traditions suggest that the Siwai migrated from New Guinea and have occupied their present territory for at least 2,000 years, and likely far longer. They share their closest linguistic ties with the Buin people to the south and, to a lesser extent, with Nagovisi to the north. Before European contact, interaction with other groups was limited, though there was some intermarriage, trade—particularly with Alu and Mono in the Solomon Islands—and occasional small-scale warfare. Before the 20th century, Siwai communities experienced intermittent feuding and small-scale warfare, sometimes involving neighboring groups. These conflicts were organized by mumis, but they were usually limited in scope and casualties. Individual disputes rarely escalated into open hostilities. In modern times, such traditional warfare has disappeared. However, internal divisions persist, often along religious lines—Catholic versus United Church districts—which have occasionally produced local conflict. More recently, political issues such as secession and the closure of the Panguna mine have also generated tension and episodes of violence.

European trade reached the Siwai coast intermittently in the late 19th century, but aside from the introduction of steel tools, external influence remained limited until the 20th century. Around 1900, a few Siwai men worked on distant plantations and brought back new crops, with additional introductions during the German colonial period. Effective colonial administration began in 1919, when an Australian post was established on the Buin coast. Catholic and Methodist missions established stations in the early 1920s. Before World War II, small-scale copra trading developed, most Siwai converted to Christianity, monetary taxes were imposed, and many men spent extended periods working as plantation laborers on Bougainville’s east coast. After the war, cultural change accelerated. Cocoa became the main cash crop, education expanded rapidly—eventually reaching the tertiary level—traditional practices shifted, and the massive Panguna copper mine, built about 50 kilometers away, introduced new forms of employment and political engagement.

Siwai Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 95 percent of Uisai are Christians. Siwai traditional religion centered on creation stories involving powerful ancestral spirits, especially “the Maker” (Tartanu), who was said to have brought life to the earth. Numerous lesser spirits, or mara, were linked to specific places, kin groups, or men’s houses. These beings were believed to possess both helpful and harmful qualities, though there was no formal system of worship or ritual that structured people’s relationships with them. While mara are still feared, Christianity has largely replaced traditional beliefs, and most Siwai today are adherents of either the Catholic or United Church. Several small revival movements have also emerged in recent decades. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Death was traditionally considered a natural event, especially for the elderly, though in unusual cases it might be attributed to sorcery or the influence of mara. After death, the soul was believed to journey to one of three destinations: “Paradise,” a lake in northeast Siwai for well-mourned spirits; “Kaopiri,” a northern lake for those insufficiently honored; or “Blood Place,” reserved for those killed in fighting. These ideas have largely been replaced by Christian concepts of Heaven and Hell.

Religious Practitioners and Healing: There were no priests or formal ritual specialists, though mumis and sorcerers (mikai) were thought to exert some control over the spirit world. Disease could arise from malevolent spirits, broken taboos, or other supernatural causes. Healing involved ritual precautions and an extensive knowledge of herbal medicine, practiced by both men and women, with some individuals specializing in skills such as bone-setting. Sorcerers were believed to repel harmful spirits or send them to punish enemies. Today, Western medicine is widely sought for modern illnesses, though traditional remedies remain in use.

Ceremonies: A cycle of ceremonies marked the major stages of life. Betrothal involved exchanging strings of shell money, while marriage was accompanied by magical rites to ensure the couple’s wellbeing. Baptisms traditionally took place four or five weeks after a child’s birth. The transition to adulthood was marked with little ceremony. The most elaborate rituals surrounded cremation and the close of mourning periods, events characterized by the exchange of pigs, shell valuables, and other goods.

Arts: Music and dance play central roles in memorial ceremonies. Men’s and women’s performances are distinct and held separately. Large slit gongs housed in men’s houses are struck in unison during ceremonial preparations. Men’s dances feature panpipes and wooden trumpets, while women’s dances are accompanied by a wooden sounding board. Few traditional crafts are still produced. Pottery disappeared soon after World War II. The notable exception is the finely woven “Buka baskets,” almost all of which are actually made in Siwai. These baskets are produced in significant quantities in several villages and sold widely across Bougainville and beyond.

Siwai Society and Family

Siwai society consists of numerous matrilineages, though most villages are dominated by two major lineages that have intermarried for generations. These paired lineages function as local descent groups, each with its own wealth stores and landholdings. Interaction among matrilineage members is frequent and central to social life. Siwai kin terms are similar to Dravidian-type systems associated with two-section structures, bilateral cross-cousin marriage, and sister exchange. Genealogical depth is shallow, and strictly affinal terms are few. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Households are usually nuclear families; extended households are uncommon. Young people often sleep in separate houses. Parents generally treat children with indulgent affection, and discipline—mostly verbal—tends to be mild and often ineffective. Conflicts are more common between siblings than between children and parents, who are afforded notable respect. Primary schooling is now universal, with many youths continuing to secondary and tertiary education. Personal belongings are usually inherited by the eldest son, though until recently such inheritances were minimal.

Marriages, traditionally, favored both matrilateral (through the female line) and patrilateral (through the male line) cross-cousins, and matrilineages were often paired for generations of intermarriage. Marriage within one’s own matrilineage was strictly forbidden. Polygyny occurred in the past, especially among leaders, but is now rare. Divorce was common, and widowed spouses typically remarried. While cross-cousin marriage remains common, many unions today involve partners from other linguistic groups. Residence after marriage was initially virilocal, but often shifted later to avunculocal or uxorilocal patterns.

Political Organization: Historically, Siwai did not form a unified tribal group beyond sharing a language. During the prewar period, the colonial administration appointed village representatives, but Siwai only became an effective political entity in the 1960s with the creation of a local government council. The area traditionally consisted of seven districts and returned to a more decentralized pattern in the 1970s with the introduction of community governments. Most villages now maintain their own councils. Politically, Siwai elects two members to the North Solomons Provincial Government and belongs to the national South Bougainville constituency. Traditionally, big-men played a central role in maintaining social order, gaining prestige partly through this ability. In the 1920s, colonial administrators appointed village headmen, though their authority rarely matched that of traditional leaders. A formal court system developed alongside the local government council but has since been replaced by village courts associated with community governments. Serious offenses are handled at the provincial level. Traditional leaders now wield less influence over social control. Avoidance behavior also played a role historically, and sorcerers once held considerable authority—power that today is more often exercised by church leaders.

Before sustained outside contact, age offered some status, but real prestige rested with traditional leaders or big-men (mumi). The most renowned in recent times was Soni of Tutuguan. Leadership was achieved—not inherited—through wealth, renown, and personal qualities such as industry, charisma, strategic skill, diplomacy, and strong kin backing. Wealth was accumulated in pigs, land, and sometimes multiple wives, and was redistributed at funerary feasts and other exchanges. Although many men held varying degrees of prestige, there was no formal ranking system. Women exercised significant authority within their own productive and ritual domains, though they were not recognized as leaders in the same way. After World War II, leadership shifted as businessmen and politicians gained influence, feasting declined in importance, and many men spent long periods away from their villages. Women’s economic independence diminished with the growing cash economy.

Siwai Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Siwai have long been horticulturalists. Until World War II, their system centered overwhelmingly on taro—more than fifty varieties—which supplied around 80 percent of the diet. Yams, sweet potatoes, sugarcane, bananas, and leafy vegetables supplemented it, along with tree crops such as coconuts, breadfruit, sago, and almonds. Pigs were central to exchange and feasting, and fish and prawns were gathered from small streams. Taro blight in the early 1940s devastated their main crop; despite repeated efforts to revive taro, sweet potatoes have since taken its place as the dominant staple. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

After the war, Siwai communities attempted to withdraw from plantation labor and establish commercial agriculture. They experimented with rice (a prestigious food), peanuts, corn, and coffee, but market access was too limited for sustained success. Cocoa, introduced in the late 1950s, became viable once roads connected Siwai to the Buin coast in the 1960s and the east coast in the 1970s. After various failed commercial ventures, including cattle, cocoa emerged as the sole successful cash crop and is now cultivated by nearly all households. Cash income today comes mainly from cocoa, local vegetable sales, limited wage employment, and remittances from Siwai working at Panguna and elsewhere.

Work: Agriculture has traditionally been women’s work; in the early twentieth century, women spent four times as many hours in the gardens as men. Men helped with clearing, hunting, performed garden magic, and organized ceremonial events. The shift to sweet potatoes reduced women’s work demands, while cash cropping became primarily men’s responsibility. Garden magic declined, as did time devoted to ceremonial life. Many men—and some women—now work in local wage labor, and many more are employed outside Siwai at the mine and in urban centers.

Settlements: Before colonial administration, Siwai lived in small, dispersed hamlets of one to ten houses located on matrilineage garden lands, with houses built directly on the ground. In the 1920s the Australian administration consolidated these scattered settlements into about sixty line villages to ease governance and improve sanitation. New houses were built on piles and placed on ridges near springs and large streams. Many families continued to maintain both their village houses and their original hamlet houses. Since independence and with growing pressure on land, some families have moved back to the original hamlet sites. Most villages traditionally included at least one men’s clubhouse (kaposo)—a large structure used for gatherings, slit-gong drumming, and feast organization. A century ago, some were elaborately decorated. Houses were typically made of wood, woven bamboo walls, and sago-leaf roofing, though from the 1970s onward some more durable houses appeared, occasionally with generators, water systems, or solar power. Villages have remained in roughly the same locations through historical times, while mission stations, schools, and administrative buildings built outside villages have not developed into independent settlements.

Trade: In the nineteenth century, Siwai engaged in extensive trade and intermarriage with the nearby Solomon Islands. Shell money from Malaita was a key trade item. By the early twentieth century, trade with Europeans grew rapidly with the expansion of monetization and mission influence, largely replacing earlier Melanesian exchange networks—though shell money remained in circulation until recently. In 1956 the Siwai Rural Progress Society was formed to market cocoa, copra, and other products; it expanded in the 1960s and 1970s but eventually collapsed as individual growers shifted to selling directly to east coast buyers. Today, most villages maintain at least one trade store.

Land in Siwai is owned by matrilineages. Each lineage controls its own garden lands or potential garden sites and often claims hunting grounds or fishing streams. Land was occasionally alienated under exceptional circumstances, and a few parcels today are individually owned. Men garden on their wives’ land, and high rates of cross-cousin marriage once helped preserve matrilineage land continuity. Increasing population density, changing marriage patterns, and widespread cocoa cultivation have made land tenure and inheritance considerably more complex.

Nagovisi

The Nagovisi are an indigenous people of southwestern Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, living in the rugged, tropical interior of the island’s southern mountains. The Nagovisi speak Nagovisi (Sibe), one of Bougainville’s Papuan (non-Austronesian) languages. There are roughly 5,000 speakers of the Nagovisi language—though some sources estimate a broader population of around 15,000. [Source: Google AI]

Nagovisi society is matrilineal, with land rights, inheritance, and key social identities passed through the female line. Traditionally, communities were organized into dispersed hamlets, with leadership centered on “big men”, whose influence derived from skill in diplomacy, exchange, and organizing warfare and feasting. Women have long held central economic authority, especially in food production, while men assist mainly with heavy labor. Today, the Nagovisi are overwhelmingly Christian—about 97 percent, according to the Joshua Project—with an estimated 10–50 percent identifying as Evangelical.

Subsistence agriculture remains at the core of daily life. The Nagovisi cultivate taro, sweet potato, and other root crops using shifting cultivation methods, and they raise pigs, which play an important role in exchange and ritual life. Since the mid-20th century, cocoa has become their major cash crop. Anthropological research notes that the rise of cocoa production has, somewhat unexpectedly, reinforced rather than weakened matrilineal institutions, as women retain strong control over land and gardening.

Nasioi

The Nasioi, also known as the Kieta, occupy a broad area of southeastern Bougainville, extending from the coastal region around Kieta Harbour inland for about 29 kilometers, between 6° and 6°12' S. Their settlements historically ranged from the coast through interior valleys to elevations of about 900 meters, giving them access to multiple ecological zones. This distribution shaped traditional patterns of exchange and influenced how different communities experienced colonialism and modern social change. Sea-level temperatures average 27°C, with greater variation across a single day than between months. Temperatures drop roughly 3.5°C per 300 meters of elevation. Annual rainfall—about 300 centimeters—is high and evenly spread throughout the year. [Source: Eugene Ogan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Although “Nasioi” has been widely used by Europeans since the early 20th century, it is best treated as a linguistic designation. Speakers traditionally identified themselves by more local names. The ethnonym “Kietas” is now commonly used by other Bougainvilleans and missionaries. Contemporary estimates place the Nasioi population at roughly 28,000. In 1963, the number of Nasioi speakers was estimated at 10,654, and rapid population growth since then likely raised the figure to around 14,000 by 1980. The language—also called Naasioi, Kieta, Kieta Talk, or Aunge—is spoken from the central mountains to the southeastern coast of the Kieta District.

Language: Nasioi belongs to the Nasioi Family within the Southern Bougainville branch of non-Austronesian (Papuan) languages, closely related to Nagovisi. Several distinct dialects exist, and many villages include speakers of additional languages. Today, most younger Nasioi also speak Tok Pisin and/or English.

See Separate Article: NASIOI OF BOUGAINVILLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

Tinputz

The Tinputz people live in the Tinputz district of northern Bougainville Island. Also known as Buka, Timputs, Kurtatchi, Wasio and Vasui, they speak the Tinputz language and are involved in activities like cocoa farming. The Tinputz also include Teop people from the coastal area on Teop island. Both the Tinputz and Teop are increasingly being affected by climate change, leading to displacement and community resilience efforts, and characterized by strong faith and active engagement in cultural and disaster preparedness activities.

The Tinputz people are associated with Kurtatchi, a single village described in Beatrice Blackwood’s classic 1930 ethnographic study. Tinputz speakers live in the northernmost part of Bougainville Island, close to the passage separating Bougainville from Buka at roughly 5° S and 154° E. Their territory is rugged, rising from sea level to about 100 meters, with steep slopes, temperatures of 22°–32°C, and 250–300 centimeters of rainfall distributed fairly evenly throughout the year.

According to the Christian research group Joshua Project, the Tinputz population in the 2020s was about 10,000. In 1930, Kurtatchi village held 136 residents, while pre-contact Bougainville is estimated to have had about 45,000 people. By 1963, there were roughly 1,390 Tinputz speakers, and the island’s population has increased sharply since then.

Climate change has pushed some communities from outer islands to relocate to the Tinputz region, where they are gradually integrating with local residents. The area is also active in disaster-preparedness planning, including the creation of community-level disaster management strategies. Government projects, supported by organizations such as the World Bank, are upgrading local infrastructure—particularly roads—to better support agriculture and village life.

Tinputz Language belongs to the Austronesian family. Together with Teop and Hahon, and in association with Petats, Banoni, Torau, Nissan, and Nahoa, it forms part of the Bougainville Austronesian stock. Today, most younger speakers also use Tok Pisin, the national lingua franca, or English.

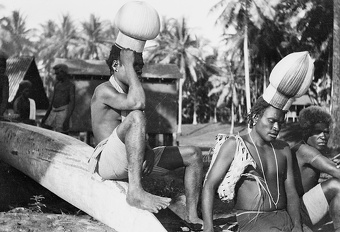

History: Archaeological evidence shows human occupation on nearby Buka Island for more than 28,000 years. Austronesian-speaking groups such as the Tinputz are considered later arrivals compared to the non-Austronesian speakers of southern Bougainville, though Austronesian languages were almost certainly present in the region by over 3,000 years ago. Austronesian communities on northern Bougainville and Buka formed a distinct cultural sphere, noted for large plank canoes, a stronger maritime orientation, male initiation ceremonies, inherited political rank, prohibitions on cross-cousin marriage, and, likely, cannibalism. Before colonization, sporadic warfare was common between coastal and inland communities and among coastal groups themselves. A tsunaun (leader) was responsible for leading his village, or several villages, in such conflicts. Fighting typically involved small-scale raids or ambushes rather than open battles, and taking captives for cannibalism was one motive for warfare. Colonial authorities made ending such conflict a priority, yet inland groups continued raiding coastal Tinputz villages until after World War II.

Bougainville was first sighted by Europeans in 1768 and was claimed by Germany in 1886. Australia administered the former German New Guinea from 1914 until Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975, after which Bougainville became part of the North Solomons Province. From the early 1900s to World War II, Europeans established coconut plantations in the Tinputz region, while Tinputz people also worked on plantations both locally and elsewhere in the Pacific. Japanese occupation during World War II inflicted heavy damage on the island and its inhabitants. Since then, rapid political and economic change has often brought social disruption throughout Bougainville, including in the Tinputz area.

Tinputz Religion and Culture

Christianity is widespread in the Tinputz region, with most people actively participating in church life. The Joshua Project estimates that about 98 percent of Tinputz are Christian, with Evangelicals making up somewhere between 10 and 50 percent. Roman Catholic missionaries arrived in 1902, followed by Methodist and Seventh-day Adventist missions after World War I. Today, the Methodist (now United Church) has a particularly strong presence in Tinputz communities. [Source: Eugene Ogan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Tinputz cocoa farmers, from pngbuzz

To early Western observers, Tinputz daily life appeared saturated with supernatural concerns. Nearly every activity involved spells, magical practices, or attention to spirit beings. The Tinputz did not recognize a category of deities in the Western sense; instead, the most significant spirits were those of the dead. These spirits—regarded with both fear and potential usefulness—could be placated or called upon to assist in gardening and other work. The word ura was used both for ancestral spirits and for spirits believed to inhabit particular places.

Death and Funerals: Except for infants and the very old, all deaths were attributed to hostile humans or malicious spirits. The dead were believed to journey to Mount Balbi, an active volcano, although some spirits remained nearby as ura. Coastal communities once disposed of bodies at sea, but burial became common even before Christianity took hold. Widows were expected to observe extended mourning, and the death of a tsunaun (leader) required mourning by the entire village.

Religious Practitioners: Traditionally, there were no full-time ritual specialists, but many individuals possessed particular knowledge that could influence events—each village, for instance, typically had its own rainmaker. Today, mission teachers and United Church pastors play central roles in community religious life. Traditional Tinputz beliefs made little distinction between healing and ritual practice. Illness was attributed to malevolent spirits or sorcery, and although plant-based remedies were used, their power was thought to be spiritual as much as medicinal. Western medicine later eradicated diseases such as yaws and Hansen’s disease, though malaria remains a serious concern.

Ceremonies and Art: Life-cycle rituals were the most important ceremonies, but spells and magical substances could accompany almost any activity. With missionization came Sunday worship and other Christian observances. Music, dance, and the arts were deeply integrated into ceremonial life. Slit gongs, wooden trumpets, panpipes, bullroarers, musical bows, and Jew’s harps were played on specific occasions. Everyday items—lime pots, canoe paddles—were often decorated, while carved wooden figures, especially depictions of ura spirits, were closely tied to religious practice.

Tinputz Society and Family

Traditional Tinputz society was relatively egalitarian compared with many other Melanesian groups. Relations between men and women tended to be complementary rather than hierarchical, and both could inherit high rank. Today, differences in wealth and education are more evident. Historically, Tinputz hamlets appear to have operated as autonomous units. Within each hamlet, the senior man and woman of the leading matrilineage were recognized as tsunaun, “persons of importance.” Their authority before European contact is uncertain, but the role seems to have centered on influence and prestige rather than formal political power. Tsunaun were accorded great respect, and major stages of their lives were marked by elaborate ceremonies. High-ranking men commonly had multiple wives. Rank was not based on property, and succession followed the matrilineal line. Under German and Australian rule, colonial administrators appointed village headmen, and today Tinputz communities elect representatives to both the Provincial Assembly and Papua New Guinea’s national parliament. A tsunaun was traditionally expected to settle disputes within the hamlet and may have been able to order the execution of someone who persistently violated social norms. Far more pervasive, however, was the fear that an aggrieved person might retaliate with harmful magic. Anger was commonly expressed by destroying one’s own possessions. Today, the Tinputz are governed by Papua New Guinea law, including a system of village courts for local dispute resolution. [Source: Eugene Ogan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Households traditionally consisted of a married couple and their young children. In polygynous marriages, each wife maintained her own house. Occasionally an elderly parent lived with an adult child. During initiation, adolescent boys resided in the men’s house. Today the nuclear family remains the norm, though older children often leave the village for secondary schooling. A child’s daily life was most shaped by their maternal kin group, and fathers played an active role in childcare. Many stages of childhood—emergence into public life, the first trip to the garden—were marked with ceremonies, especially for high-ranking children. The most distinctive feature of Tinputz socialization was the initiation of boys with the upe hat: a cylindrical or melon-shaped structure made of fan-palm leaves stretched over a bamboo frame. Boys, beginning around age eight or nine, wore the upe for several years and were not to be seen by any woman without it. Initiation concluded with the removal of the hat and the cutting of the boy’s long hair. Girls, particularly eldest daughters or those of high rank, might experience seclusion and ceremony at first menstruation, though this was not universal. Today, both boys and girls undergo formal schooling, at least through the primary level, with some continuing to higher education.

Marriage: According to Blackwood, there was no preferred marriage form, only prohibitions. Both cross cousins and parallel cousins were forbidden as spouses. Child betrothal was common, arranged between the boy’s father and the girl’s mother. Marriage involved a series of exchanges between the two kin groups, including a bride-price paid in porpoise or flying-fox teeth. Polygyny was practiced only by high-ranking men. A man might inherit his brother’s widow, and a widower could claim his deceased wife’s sister. Post-marital residence was uxorilocal, and divorce was frequent and easily arranged. Today, polygyny and child betrothal have disappeared, but bride-wealth is still paid in traditional valuables. Young people increasingly marry outside their language or ethnic group, especially those pursuing formal education and European-influenced lifestyles.

Kinship: The core social unit is the matrilineage, usually occupying a single hamlet and holding ultimate rights to the land. Matrilineages were grouped into exogamous clans that, because they were widely dispersed, generally did not act as unified corporate entities. As in many Bougainville societies, Tinputz people showed little interest in long genealogies. Tinputz kinship terminology follows a variant of the Iroquois (bifurcate-merging) system. Parallel cousins—the children of a father’s brother or a mother’s sister—are classified as siblings, while cross cousins—the children of a brother and sister—are distinguished terminologically and considered potential spouses. As in other Iroquois systems, same-sex siblings of one’s parents are called by parental terms, while opposite-sex siblings are labeled with terms commonly translated in English as “aunt” or “uncle.”

Tinputz Agriculture, Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Cocoa farming is now a major element of the local economy, supported by infrastructure projects that improve farmers’ access to markets. Traditionally, the Tinputz were typical Melanesian swidden horticulturalists who relied heavily on taro as their staple crop. Coconuts were grown for food and, with administrative encouragement after European contact, became an important cash crop. When a taro blight swept Bougainville during World War II, sweet potatoes gained prominence in the diet. Bonito fishing was a key male activity. Before World War II, some Tinputz men worked as plantation laborers both locally and elsewhere in the Pacific, but later devoted more time to cultivating their own cash crops. [Source: Eugene Ogan, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Work was traditionally divided by gender as is the case in many Melanesian societies. Men cleared land, built houses, fences, and canoes, hunted, and fished beyond the reef. Women tended gardens, cooked, collected shellfish and other marine resources, and carried most of the responsibility for childcare. Traditional crafts included canoe building, wood carving, and the production of mats, baskets, and pandanus-leaf rain hoods. Most of these skills continue to be practiced. During the colonial era, men were far more active in wage labor and remain overrepresented in higher education and the cash economy, though women today also cultivate and sell cash crops. Tinputz with higher levels of education increasingly participate in the modern urban workforce.

Hamlets traditionally were scattered along coastal areas — often on cliffs rising from the shore and, less commonly, a short distance inland. Government and mission pressure encouraged settlement consolidation, but precontact hamlets were likely smaller. Houses were aligned and the hamlet was fenced except on the seaward side. A central feature of each settlement was the men’s house, used especially during boys’ initiation. Homes were built on the ground from sago-palm thatch and shaped in a distinctive broad Gothic arch, characteristic of northern Austronesian speakers. Australian administrators later promoted raised houses for hygiene, and today some Tinputz use European-style materials and floor plans.

Trade was traditionally revolved around coastal and inland communities exchanging fish for taro. The Tinputz also traded for pottery from Buka. Two traditional currencies circulated: strings of flying-fox or porpoise teeth, and strings of shell disks. These were used only for major social transactions such as marriages. In the nineteenth century, coastal people began occasional trade with European ships, exchanging coconuts and food for metal tools and other goods. Early in the colonial period, European authorities imposed a head tax that accelerated the development of a cash economy. Islanders responded by producing copra and taking on wage labor. Today, nearly all Tinputz participate in the modern cash economy to some degree.

Land Tenure and Inheritance: Blackwood described land as belonging to the village, with management rights held by the highest-ranking clan. In practice, access to land likely depended on several social connections, including clan membership, residence, marriage ties, and individual kin networks. Productive trees could be individually owned, a factor that has become increasingly important as land is planted in cash crops. Rising interest in individual land claims—reflecting European patterns of ownership—has led to more disputes. Traditionally, many of a deceased person’s property items, including pigs and productive trees, were consumed or destroyed during funerary rites, limiting inheritance. Rank and traditional valuables passed matrilineally, but today cash-crop trees and money typically pass from parents to children of either sex.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025