Home | Category: Island Ethnic Groups / Arts, Culture, Sports

MASSIM

The Massim region is an anthropologically defined cultural area of Papua New Guinea that encompasses the eastern tip of the New Guinea mainland and the adjacent offshore islands and embraces the Kula Ring and Milne Bay Province. Situated off the southeastern tip of New Guinea, the Massim region consists of a series of small, widely scattered archipelagos whose arts and cultures are linked by an intricate network of voyaging and trade.

Massim culture is visible throughout the islands off southeastern New Guinea, especially in the Louisiade Archipelago. According to Australia National University: The cultural identities and social organisation of the Massim inhabitants have been the focus of international attention amongst anthropologists since the beginning of colonial pacification in the mid-late 19th century. Archaeologically, however, the Massim islands have not been as well represented. [Source:Australia National University]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: By far the most important trading activity in the Massim is the kula, a complex system of exchange relationships between individuals on different islands, through which ceremonial valuables in the form of necklaces and armbands continually circulate. Success in the kula, which remains vigorous today, is the primary means through which an individual achieves wealth and renown. The participants, valuables, and vessels involved in the kula are surrounded by rituals, restrictions, and magic intended to ensure a safe voyage and success in obtaining the most coveted examples of the valuables. The accumulation, exchange, and display of ceremonial valuables formed, and continues to form, one of the central themes in the arts and cultures of the Massim region. Many types of Massim valuables consist of exaggerated versions of ordinary objects — such as armbands or implements-which are too large, too small, too fragile, or too ornate for practical use. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

According to Encyclopedia Britannica: The kula trading cycle distributed not only shell valuables — the ostensible motive of the transactions — but also quantities of other goods. Notable among these were carvings in dark hardwood. In the Massim, people traded pottery from the Amphlett Islands and canoe timber and greenstone blades from Muyua (Woodlark Island). Carved platters, canoe prow boards, and other specialized products were complemented by a flow of yams and pigs from areas with rich resources to smaller, ecologically less-favoured. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROBRIAND ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, BIG MEN POLITICS, ECONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com

TROBRIAND ISLANDER CULTURE: CUSTOMS, MATRILINEAL SOCIETY, SEX AND YAMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ISLANDERS OF NORTHERN PAPUA NEW GUINEA ON MANAM, WOGEO AND MANUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA ISLANDERS OF MASSIM, MILNE BAY AND DOBU, ROSSEL AND GOODENOUGH ISLANDS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHEAST PAPUA NEW GUINEA: MEKEO, MAILU, WAMIRA ioa. factsanddetails.com

EAST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — THE BAINING AND TOLAI — AND THEIR CUSTOMS, LIFESTYLES AND DANCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WEST NEW BRITAIN ETHNIC GROUPS — NAKANAI, AROWE — AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MASKS AND ART OF NEW BRITAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

NEW IRELAND ETHNIC GROUPS — MADAK, LESU, AND LAK— AND THEIR TRADITIONS AND SOCIETIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ART FROM NEW IRELAND: MALAGAN, FUNERARY FIGURES AND DRUMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BOUGAINVILLE ISLANDERS — SIWAI, TINPUTZ, NAGOVISI — AND THEIR HISTORY, SOCIETIES AND CULTURE ioa.factsanddetails.com

NASIOI OF BOUGAINVILLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE, SOCIETY ioa.factsanddetails.com

NISSAN ISLANDERS: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Massim Canoe-Prow Ornament

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The ornate canoes created for kula voyages are the most visually striking of all Massim art forms: they are lavishly carved and painted, and embellished with glistening white cowrie shells and streamers that flutter in the wind. Carvers of kula canoes devote most of their efforts to the ornaments that adorn the prow and stern. In most cases these ornaments are identical, giving the canoe two "front" ends, which allows the craft to be rigged and sailed in either direction. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The canoe ornaments consist of two main components: a prow ornament, such as the present work, which projects outward from the bow (or stern), and a splash board, attached transversel behind it, which prevents water from splashing into the canoe as it cuts through the waves.

Massim artists produce two basic forms of kula canoes and prows. Canoes with the distinctive rising-crescent-shaped prow ornament seen here, referred to in the Trobriand Islands as nagega, are produced in man parts of the region. The present work is attributed to the southern Massim island of Suau. According to Cecil Abel, a southern Massim man and leading authority on the region's art, canoes on Suau were sacred objects associated with the ancestors.

An individual could create ordinary objects, but the adornment of canoes was a sacred activity, restricted to members of certain families. A single artist, called tau pusa pusa (the man who carves), was responsible for both the supernatural and the physical crafting of the vessel although he might be assisted by others in labor-intensive tasks. such as hollowing the hull. In the community the grace, virtuosity and correctness with \which the carver executes the designs are both praised and critiqued. Of a well-carved design onlookers might remark, ta'i iloro (it's so beautiful) or i mata ai (it eats my eye). terms that could be applied equally to the admiration of a beautiful woman. Although the artists covered virtually the entire prow ornament with ornate relief carvings, in creating the prows of nagega canoes the left a plain, tablike projection at the tip to serve for the attachment of a separately made charm.

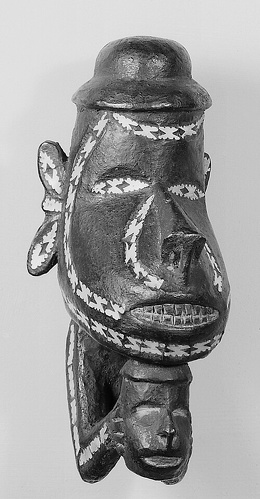

Massim Charm (Munkuris)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Massim charms are no longer produced today; many of them appear to have been made on the northern Massim island of Marua, where they were called munkuris, but they may have been carved in other areas as well. Attached to the tip of the prow of canoes the munkuris appears to have served a protective function, safeguarding the vessel during the hazardous ocean crossings of the kula voyages.

Such charms and accompanying ornaments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art were probably made on Suau Island Morua (Woodlark) Island in the 19th-early 20th century from wood and paint. The ornament is 47 inches (119.4 centimeters) long and the charm 18.8 inches (43 centimeters) high. The charm shows the characteristic imagery of these charms. The base is adorned with white birds, probably boi (reef herons)· the black forms on their wings represent asiwan, a type of fish, and the curving, comma-shaped forms that spring from the tips of the beaks represent the shells of the chambered nautilus (ovagoro). [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

As described by Arubutau, a chief from the Trobriand Islands, these charms, known there as skusabo, were also important symbols of the kula, and their appearance on the bows of visiting trading canoes required an offering from the hosts: "When a nagega canoe is about to land on a kula expedition and the people on the shore see the skusabo, the immediately run to bring a pig. If the don't, the canoe will turn back; the skippers will sa : these people don 't know anything about kula."'

Massim Ceremonial Axe

The Massim Ceremonial Axe is a wood, stone, fiber implement made by the Massim people. Dating to the mid-to late 19th century, it is 27.37 inches high, 11.75 inches wide, with a depth of 1 inches (69.5 × 29.8 × 2.5 centimeters). [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: This object is one of the most important types of valuables that still circulate in the area. The axe has a greenstone blade and a carved wooden haft. The axe blade is inserted into the wooden handle, carved in the shape of a slightly tilted forward ‘7’. The blade is made of polished ignimbrite stone sourced in one of the few volcanic islands of the Massim region. It is fitted into the previously slit axe’s head and wrapped with fibers fastened around the incision to secure the blade in position. The axe shaft is made of red hardwood; it is flat in shape and follows an acute angle, with the stone head close to the body of the handle. The haft is carved in bas-relief with a serpentine motif known as mwata, a mythical snake. The mwata descends from the pointed tip where the blade and the shaft meet towards the center of the handle where it ends in a coiled loop pattern, leaving the rest of the haft undecorated except for the axe’s knob at the very bottom. Here, the handle has been cut in the shape of a stylized open mouth characteristic of Massim carvings.

Before the introduction of iron by Euro-Americans in the 19th century, stone axe blades were precious items in the Massim, where most islands are coral atolls lacking hard rocks to be used as wood-cutting tools, indispensable for making food gardens and constructing seagoing canoes. After iron tools became common, polished axe stones retained their status as traditional ceremonial valuables traded in the region. In the Massim, the valuable item is the greenstone axe head proper. Wooden handles are only temporary supports for the blade, carved especially to carry and display the stone during exchange ceremonies. Once it has been inserted in the haft, the stone blade is marked for presentation and exchanged, after which the handle is often discarded until the next exchange cycle demands that a new one be carved.

Archaeological evidence points to a long-extinct greenstone tool industry centered around the quarry of the Suloga hills in Muyuw (Woodlark Island). A common belief throughout the region is that greenstone self-reproduces in river estuaries and water holes where it is normally found, and that people collect these stones and polish them into axe blades. Blades are graded into different named categories depending on their size, polish, hue and the pale green streaks sometimes found in the stone (referred to as “clouds”). The exchange value of each stone is fixed and determined by their dimensions and characteristics. When fitted in the haft, ceremonial axes in the Louisiade Archipelago of the southern Massim region have a detailed anthropomorphic symbolism in which parts of the axe’s handle correspond to body parts. The handle as a whole is considered to be an arm, where the angle is the elbow and the part that holds the blade in place is the hand. The carved mwata snake motif alludes to a creation myth narrating the fight between a giant snake and a colossal buzzard in the southern Massim. The buzzard killed the snake, scattering the bones of the serpent to form the coral atolls of the Calvados Chain.

Greenstone blades are equally important in ceremonial exchanges in many other parts of the Massim, although the shape and symbolism of the carved wooden handles found in other islands may vary when compared to the southern Massim. The relevance of polished greenstone blades in the area is such that people embark on long journeys aboard locally-made dugout canoes with the sole aim of obtaining these valuables ahead of planned funerary rituals.

High Value of Massim Ceremonial Axes

Ceremonial axes were, and are, prized by all Massim peoples. Eric Kjellgren wrote: These axes consisted of two components, the blade and the handle, which were of different origins. All the blades originated on a single island, Marua, in northern Massim, from which they were reportedly exported in rou gh form to Kiriwina, in the Trobriand Islands, to be ground and polished and then traded throughout the region. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Prized and evaluated according to their size, their thinness, and the subtle mottling of their stone, the blades were by far the most valuable element of the ax. The finest examples often had personal names. Owned by chiefs and other prominent men, some ax blades became family heirlooms, which were never traded and seldom displayed.' Most, however, served as a permanent store of wealth and form of ritua l currency; they were, and are, exchanged to purchase commodities, such as pigs, canoes, or land, to settle disputes, to pay for dance performances, or to secure the services of religious specialists. On the southern Massim island of Sabarl, remote in space and time from their point of origin, ax blades are believed to be natural rather than manufactured, fantastic objects that grow like seashells in shallow estuaries where fresh and salt waters mingle.

The blades were traded from afar, but the handles, which were often valuable objects in their own right, were created locally. The graceful, delicately carved handle of the present work is from the southern Massim region, where ceremonial axes were often carried by women during dances at harvest celebrations. Many southern Massim ax handles are adorned, as here, with sinuous images of stylized birds. However, on Sabarl, the shape of ceremonial axes, known locally as tobwatobwa, represents both the outward form and the vital power of the human body. The blade is identified as the hinona (vital substance) of the ax and symbolizes the right h and or reproductive organs, which are associated with the hinona of the human body. The plaited fiber around the base of the blade is also called the hand, and the ascending portion of the shaft represents the arm. The top of the ax forms the head; the handgrip represents the leg, and the carved finial at the end of it the foot. Conceived thus, as tangible images of the physical and spiritual power of the human body, ceremonial axes represented more than simple currency.

Massim Lime Spatula

Massim lime spatulas were used in the chewing of betel nut. They were bladelike implements used to scoop a small quantity of lime from a gourd container and into the user's mouth. The lime helped activate the psychoactive chemicals in the betel nut The Lime Spatula/Currency Holder in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection is made of turtle shell by Massim people in the Louisiade Archipelago in the southern Massim region, Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. Dating to the 19th-early 20th century, it is 11.25 inches high, with a width of 6.25 inches and a depth of.12 inches (28.6 x 15.9 x 0.3 centimeters).

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: This ceremonial lime spatula or lime stick is known as wonamo jilevia — literally "tortoise-shell" — in Vanatinai, the island in the Massim region of southeast Papua New Guinea where it was most likely made. Lime spatulas are usually employed to bring lime made of burnt coral to the mouth, where it adds to a mix that also consists of betel nut (Areca catechu) and betel pepper leaves or inflorescences (Piper betle). The resulting mix is a mild stimulant consumed in many parts of southeast Asia and the western Pacific, as well as throughout the Massim region, where betel nut chewing is a common practice. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The lime spatula is made out of sea turtle shell, thinly cut and embellished with incisions. The shell is translucent and has varying shades of brown, raw sienna and yellow tan. The end that corresponds to the handle of the lime spatula is shaped as a crescent, curving down to each side of the spatula’s shaft. The shaft stems from the inner center of the crescent, tapering towards its rounded tip. The outer part of the crescent has small holes punched all along its length.

Original decorations would have included small flat disks made from red Spondylus shells sewn together through the spatula’s perforations around the perimeter of the crescent-shaped handle. The inner part of the curved handle is incised with interlocking scroll patterns. Its extremities bend towards the shaft and are attached to it through two curvilinear motifs carved out of the turtle shell to each side of the shaft. Two stylized bird heads, incised with long, straight beaks facing away from each other, separate the top part of the shaft from the center of the crescent handle.

Another lime spatula in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection made of wood from roughly same place and time is .75 inches high, with a width of 29.25 inches (1.9 x 74.3 centimeters). Another made of wood is .6 inches high, with a width of 15.75 inches (1.5 x 40 centimeters). Yet another made in Domara, Cloudy Bay, Milne Bay Province, is.62 inches high, with a width of 15 inches (1.6 x 38.1 centimeters).

On a lime spatula made of wood in 1900-1910, made by the Massim in the Suau region, Milne Bay Province, measuring 24.5 inches high, with a width of 3.12 and a depth of 3.62 inches (62.2 × 7.9 × 9.2 centimeters), the Metropolitan Museum of Art says: The identities of the individuals who created the vast majority of Oceanic sculpture remain unknown. A notable exception is Mutuaga, a master carver who lived and worked in Dagodagoisu village in the Massim region at the turn of the twentieth century. Mutuaga’s unique carving style is recognizable by its distinctive rendition of the human figure and the elegance and precision of its surface ornamentation. Mutuaga created objects for local use and, beginning in the 1890s, developed a relationship with Charles Abel of the London Missionary Society. Abel became Mutuaga’s patron and promoted his work among the growing numbers of European missionaries, traders, and visitors in the area. Lime spatulas typically were used to facilitate the chewing of betel nut, a mild stimulant. As this example is too large to have served a practical function, it may have been used locally as a ceremonial object or was perhaps intended for a European client.

Massim Wealth Holder (Gabaela or 'Nga)

On the The Lime Spatula/Currency Holder (Gabaela or 'Nga), described above, Eric Kjellgren wrote: Fashioned from turtle shell, whose mottled translucence enhances its beauty, this delicately crafted work had a dual function. In its more mundane role, it served as a lime spatula: the bladelike lower tip was employed to extract lime from a gourd container during the chewing of betel nut. However, the mushroom-shaped upper portion indicates that this work was also a gabaela, a ritual object used to hold and display its owner's wealth. The line of small holes along the upper margin once served for the attachment of small disks of bright pink and orange Spondylus shell, which served as ritual currency. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Created only in the southern Massim region, gabaela were primarily made from wood. These currency holders were among the most important valuables in the region 's ceremonial exchange network and were traded throughout the Louisiade Archipelago. A conspicuous and durable form of wealth, gabae/a were used to pay for feasts, land, canoes, and other items. On Tagula Island, where they were known as 'nga, they formed part of a woman's dowry at marriage, and larger examples were carried by women as dance accessories. Along with their dual function, the imagery of gabaela has two different interpretations, depending on how the object is oriented.

According to the people of Sabarl Island, when the gabaela is positioned with the blade pointing downward, it represents a highly stylized human face or figure: the shell disks (absent in the present work) represent the hair; the unadorned b and below them, the forehead or chest; and the tips of the curved portion, the arms and hands. Two stylized birds' heads always appear on the upper portion of the shaft, and their eyes are said to form the eyes or testes of the human image, whereas the descending blade is variously identified as the nose, leg, or phallus. However, when the gabaela is positioned with the blade pointing upward, it is interpreted as a canoe (waga): the blade represents the mast (lawalawa), the carved designs on the crescentshaped portion are the gunwales (tanatana) of the canoe, and the shell disks st and for the islands among which the vessel sails.

Importance and Value of Lime Spatulas in Massim Culture

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Lime spatulas are not used to chew betel nut. Instead, they are part of a set of ceremonial valuables used in a number of rituals in the southern part of the Massim region. Together with greenstone axe blades and shell valuables, ceremonial lime spatulas decorated with red shell disks are traded following the exchange networks that crisscross the Louisiade Archipelago. Inter-island expeditions are mounted every year where women and men sail in outrigger canoes in search of wonamo jilevia lime sticks and other ceremonial currency items to fulfil their mortuary or bride wealth obligations. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

These type of lime spatulas are considered to be a support for the presentation of the truly valuable item, the red shell disks that are strung into it, in the same way as the carved wooden handle of an axe is a support to carry and display valuable greenstone blades throughout the Massim. The more shells on the lime spatula the more valuable the object is considered, conveying the high rank of the person who gives it away on occasion of a special ritual. Ceremonial lime sticks can also be made out of carved wood in the same shape as the tortoise shell ones, in which case they are known as ghenagá in the language of Vanatinai (also known as Sudest or Tagula Island).

In some parts of the Louisiade Archipelago, these ceremonial lime spatulas are given human-like characteristics, with different sections of the spatula associated to parts of the body. When looking at the spatula with the crescent on top, the rows of shell disks sewn onto the outer edge are identified with the hair of a person. The central part of the crescent is associated to the chest, whereas the extremities to each side of the shaft are the arms. The shaft can be related to either the nose, the penis or the foot. When looking at the spatula upside down — with the crescent part at the bottom — people liken it to a dugout canoe instead. In this case, the shaft corresponds to the canoe’s mast and the crescent corresponds to the gunwales of the dugout. Viewing the lime stick as a person or as a canoe is in line with Massim ideas that attribute personhood to objects and the capacity of people to act through them. As such, ceremonial lime spatulas convey ideas of mobility, status and memory.

Finial of a Ritual Staff or Lime Spatula

On a 19th-early 20th century finial of a ritual staff or lime spatula made of wood from the Massim region, measuring five inches (13.3 centimeters), Eric Kjellgren wrote: Freestanding human figures are rare in Massim art. Instead, the majority of human images appear as embellishments on everyday objects or ritual paraphernalia. This diminutive female figure was originally the carved finial of either a large lime spatula (kena) or a ritual staff, from which it was later removed. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Human figures are a common subject on the handles of lime spatulas, especially in the Trobriand Islands, in the northern Massim region. In some instances the human figures that adorned lime spatulas were more than simply decorative. According to Narubutau, a chief from the Trobriands, the human images on the spatulas can afford protection to their owners during the hazardous sea voyages involved in the kula exchange network; an individual with the proper magical knowledge can call a tokwai (spirit) into the figure on the spatula handle to watch over him while he sleeps.

Ritual staffs were produced in the Trobriand Islands, but they appear to have been primarily employed in the southern Massim region, where they were used in some areas for healing rites and in others for malevolent magic. The tops of the staffs were typically adorned with one or two seated figures. These human images, like those on the lime spatulas, may have served as the temporary residing places for spirits-in this case, for spirits who assisted the religious specialist in the rites. Delicately rendered, with her hands clasped in front of her chest and her head bowed as if in deep thought, the subject of this intimate work appears as if preoccupied with spiritual matters. However, her identity and significance remain unknown.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, William A. Lessa (1987), Jay Dobbin (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025