Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups

SANDAUN PROVINCE (WEST SEPIK PROVINCE)

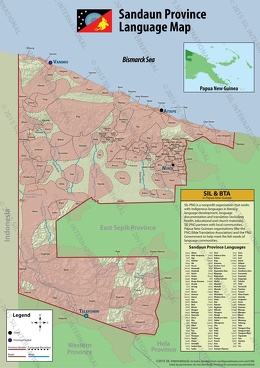

Sandaun Province, formerly known as West Sepik Province, is the most northerly mainland province in Papua New Guinea. Covering 35,920 square kilometers (13,870 square miles), it is home to 248,411 people, according to the 2011 census. Its capital is Vanimo. In July 1998, an enormous tsunami caused by a magnitude 7.0 earthquake hit the area surrounding the town of Aitape, killing over 2,000 people. Five villages along the west coast of Vanimo, heading towards the international border, are Lido, Waromo, Yako, Musu, and Wutung. The province borders Indonesia. [Source: Wikipedia]

The name Sandaun is derived from the Tok Pisin word for "sun down," as the province is located in the western part of the country where the sun sets. The province was formerly named West Sepik Province after the Sepik River, which flows through the province and forms part of its southern border.

Sandaun Province has beaches along its northern coast and mountainous areas throughout, primarily in the south. Several rivers flow throughout the province, the most notable of which is the Sepik River. Like much of Papua New Guinea, the area is prone to earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. The provincial capital is Vanimo. The province is divided into four districts: Aitape-Lumi, Vanimo-Green River, Nuku, and Telefomin. Each district contains one or more Local Level Government (LLG) areas. For census purposes, the LLG areas are subdivided into wards, which are then subdivided into census units.

Sandaun Province is home to a number of ethnic groups, including the Mian, Mitang, Telefol, Ngalum, Sandaun Yau, and Busa. These groups have distinct languages and cultural practices and maintain traditional beliefs alongside Christianity. The Mian are a fairly large group in Sandaun Province and speak the Mian language. They have related ethnic groups, such as the Telefol and Tifal. The Mitang are known for their strong connection to the land and their form of Christianity influenced by traditional beliefs. The Ngalum live in the eastern part of Highland Papua and has a presence in the Bintang Mountain Regency of Indonesia and Sandaun Province in Papua New Guinea. The Sandaun Yau number approximately 475 people who primarily practice ethnoreligion and speak the Yau language. The Busa group live in the isolated lowland rainforests of Sandaun Province. They speak the Odiai language, which is also sometimes called Busa.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEPIK RIVER GROUPS: WHERE THEY LIVE, ART, SPIRIT HOUSES, CROCODILES ioa. factsanddetails.com

KWOMA (A SEPIK RIVER TRIBE): HISTORY, LIFE, ART ioa. factsanddetails.com

EAST (LOWER) SEPIK PEOPLE — BOIKEN, MURIK, SAWIYANO — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE LOWER (EAST) SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ABELAM AND ARAPESH OF THE SEPIK RIVER: LIVES, HISTORY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa. factsanddetails.com

BIWAT (MUNDUGUMOR): LIFE, RELIGION, FAMILY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

IATMUL PEOPLE OF THE SEPIK RIVER: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHAMBRI: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CROCODILE MEN AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

Wapi

The Wapi are an ethnic group living in the Lumi District of Sandaun (West Sepik) Province. Also known as Olo, Wape, Wapei and Wapëi, they inhabit the inland slopes of the Torricelli Mountains, a rugged tropical rainforest region ranging in elevation from about 390 to 840 meters (1,280 to 2,755 feet) above sea level. In the 1990s the Wapi lived in approximately 55 villages on the leeward side of the Torricelli Mountains. Their homeland is characterized by steep ridges, dense rainforests, and numerous streams and rivers. The region experiences high humidity, heavy rainfall, and frequent earth tremors. Temperatures remain fairly constant throughout the year, with an intense wet season between October and April. [Source: William E. Mitchell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Wapi and Olo population in the 2020s was 26,000. Estimates of the Wapi population vary. In the 1990s, their numbers were estimated to be around 10,000. The name Wapi comes from Wapi, a word meaning “human being” in contrast to a spirit being — a reflection of their deep spiritual worldview.

Language: The main Wapi language is Olo, one of the 47 languages in the Torricelli Phylum, classified within the Wapii family of the Wapii-Palei stock. Olo is linguistically complex, featuring six vowels, seven diphthongs, twelve consonants, six noun classes, four verb classes, and two tenses. Most men, many children, and some women speak Tok Pisin, the national lingua franca, while students who attend secondary school often gain some fluency in English.

History: Linguistic and cultural evidence suggests that the Wapi migrated from the north coast of Papua New Guinea over the Torricelli Mountains several thousand years ago. The Wapi were generally peaceful, preferring mediation and consensus to conflict. Disputes were resolved publicly, and formal courts were rarely used. Traditional payback killings between villages occurred in the past but had already declined before colonial contact. The Sepil region came under German control in 1885, but the Wapi remained largely uncontacted until the early 20th century. The first known documentation of the group was made in 1926 by zoologist E. A. Briggs of the University of Sydney. In the 1920s and 1930s, explorers and recruiters for oil and gold ventures visited Wapi villages, which generally received outsiders peacefully.

After World War II, the area became part of the Australian-administered Mandated Territory of New Guinea. A military airstrip and base were established near Lumi, later replaced by Franciscan and Christian Brethren missions. Despite missionary influence, most Wapi have retained traditional beliefs and practices. Economic development projects since the 1940s have had limited success. The Wapi remain primarily subsistence farmers, though many men formerly worked as laborers elsewhere in the country. Today, some villages have been depopulated as families move to coastal towns for employment. A rough road now connects Lumi to Wewak, though it is often impassable due to heavy rains or landowner blockades.

Wapi Religion and Culture

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 85 percent of Wapi are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent While Christianity has a large following traditional beliefs remain deeply embedded and coexist with Western religion. The Wapi believe that all things possess a spirit, and that ghosts and ancestral beings influence daily life. When faced with misfortune, people often appeal to their deceased fathers or strong ancestors for aid. The Christian God is acknowledged but perceived as distant, whereas ancestral spirits play an immediate role in health, success, and community balance. [Source: William E. Mitchell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Religious Practitioners include 1) Numoin, shaman-witches with powers to heal or harm, fly, and become invisible; 2) Wobifs, healer who uses massage and suction to remove harmful elements; and 3) Glasman, clairvoyant diagnostician with second sight but no healing ability. Illness is generally viewed as supernaturally caused, often by demonic intrusion. Indigenous healing combines herbal remedies (e.g., ginger, stinging nettle) with exorcism rituals. While Western medicine is available at Lumi hospitals, it is often sought only after traditional cures have failed.

Major Ceremonies include the 1) Spirit Fish-Curing Festival, the largest and most socially significant, involving hundreds of participants and complex exchanges among kin; and the Mani Festival, conducted to cure illness or ensure hunting success. Dance and music are integral to curing and hunting festivals. Women and youths perform rhythmic, circular dances to the beat of slit gongs and hand drums. Masks are crafted and painted for ceremonies, and women compose lament songs upon marriage, later sung in daily life.

Death and Afterlife: The spirit is believed to leave the body through the anus, becoming a vengeful ghost who later settles on ancestral lands. Traditionally, bodies were smoked for several days before burial; modern law now requires same-day burial, though mourning customs continue.

Wapi Society, Family and Kinship

Wapi society is egalitarian, organized around nuclear families, lineages, and clans. Exchange relationships and obligations are vital to social cohesion. There are no traditional chiefs; leadership is informal and situational. Today, the Wapi participate in regional councils and national elections. Social Control is maintained through fear of ancestral spirits and sorcery, as well as communal disapproval.

Wapi families have traditionally consisted of a nuclear household, with boys moving to separate houses around puberty. Inheritance of land and planted trees is patrilineal ((based on descent through the male line). Children are gently disciplined, and most attend government-run primary schools, though costs limit attendance — especially for girls. Kinship follows the Omaha system, which groups relatives by gender and descent lines. Land is owned by patrilineages, identified by distinct slit-gong signals. Rights to garden land can be shared with outsiders or maternal kin. [Source: William E. Mitchell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Marriage is exogamous, which prohibits unions within one’s patrilineage. Women traditionally had a say in choosing partners, and bride-wealth — once paid in shells, now in money — is still customary. Polygamy is permitted but rare, and postmarital residence is virilocal (with the husband’s family). Divorce is uncommon, and widow remarriage within the husband’s lineage is typical.

Wapi Villages, Agriculture and Economic Activity

Villages are typically located on ridges and once were stockaded for defense. Each consists of multiple hamlets and clans, totaling several hundred residents. Houses are built from forest materials — either on the ground or slightly raised on posts. Each contains several small fires and sleeping benches; babies sleep with parents. A central plaza serves for children’s play, ritual dancing, and communal gatherings. Villages also include men’s houses for sacred objects and bachelor houses for unmarried males. [Source: William E. Mitchell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Men perform most hunting, gardening, and ritual work, while women handle cooking, water collection, and marketing, though both share childcare and harvesting duties. Traditional dress once included string skirts for women and nakedness for men; today, Western-style clothing is common. Men produce wooden shields, slit gongs, drums, and bows, while women make string skirts and cords.

The Wapi practice subsistence farming. Their main staple is sago, processed from palms they cultivate in swampy areas. Gardens also produce sweet potatoes, yams, bananas, coconuts, sugarcane, and tobacco, supplemented by greens, grubs, mushrooms, frogs, and bush eggs. Hunting wild pigs, cassowaries, and marsupials is highly ritualized and socially significant for men, though declining wildlife and shotgun use have reduced success. Protein deficiency is common. Formerly, the Wapi traded sago, bows, and bird feathers with coastal peoples in exchange for shells and pottery. Today, trade is limited, and small local stores often remain empty.

Telefol

The Telefol are a people of the Mountain Ok group, living in southern Sandaun (West Sepik) Province in rugged mountain terrain, dense rainforests and river valleys primarily in the Upper Sepik and Donner (Elip) river valleys, with smaller settlements along the Nena (Upper Frieda) River. Also known as Telefolmin, Kelefomin and Kelefoten, they are known for their architectural carvings, complex mythological traditions, and a unique base-27 body-based counting system. [Source: Dan Jorgensen, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

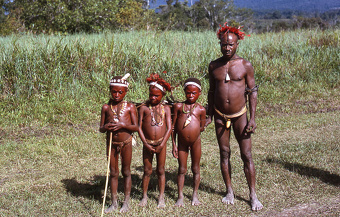

Telefol in 1963: Boys ready for the dakasalban with sponsor Oceanic Art Society

The Telefol belong to the Ok linguistic family, a network of culturally and linguistically related “Min” peoples (the suffix -min meaning “people”). Telefol are regarded by neighboring groups as holding the highest degree of ritual knowledge within this cultural system. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Telefol population in the 2020s was 15,000. In the 1990s, their population was estimated to be around 4,000.

History and Mythology: The culture heroine Afek ("Old Woman") is central to Telefol cosmology. According to myth, she founded the ancestral village Telefolip, the most sacred Yolam (men’s cult house) in the Star Mountains. Telefolip remains a focal point of ritual life. Another powerful being is Magalim, the masalai (bush spirit), known by various names including Aanang Kayaak and Bagan Kayaak. He is the “boss” of the wild — forests, animals, and untamed energies — and can take many forms: a snake, a dog, or even a ghostly European figure.

The history of the Telefol begins with Afek traveling through the land that is now the Eliptaman Valley. According to their creation stories, she founded the most sacred of the Yolam Houses, or Haus Tambaran, in the Star Mountains Region about 300 years ago. According to myth, a tunnel system exists between Mount Fubilan, the Yolam House at Bultem, and the Telefolip, through which shell money and other valuable items came to the Telefol. After the Iligimin people razed the Telefolip in the 19th century, the Telefol defeated the Iligimin people. The Telefol then settled their lands. They went on to defeat the Untoumin people, ritualistically cannibalizing the adults and absorbing the children into their group. After the annihilation of the Untoumin, the Telefolmin and the Miyanmin raided each other occasionally until the late 1950s, when pacification occurred.

The Ok Tedi mine — an open-pit copper and gold mine located near the headwaters of the Ok Tedi River — has profoundly reshaped Telefol life. Male wage labor has altered traditional gender roles — women now undertake gardening and pig husbandry independently. Migration, cash economy, and Christianity have transformed social life, yet Telefolip remains a potent symbol of ancestral power and cultural identity.

Telefol Religion and Culture

Shield at Tila, Nagatman speakers, upper Sepik, Oceanic Art Society

Since the late 1970s, most Telefol have converted to Christianity, particularly Baptist denominations, though older men and residents of Telefolip often maintain traditional cult practices. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 95 percent of Telefol are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent. [Source: Dan Jorgensen, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Joshua Project]

Myth and ritual are deeply intertwined with the landscape, and specific sites carry sacred mythic significance. Traditional religion was organized around a complex hierarchy of male initiations and ritual moieties (one of two descent groups in a society): 1) The Taro Moiety associated with fertility, gardening, and pig rearing; and 2) The Arrow Moiety associated with warfare and hunting. Each ritual rank carried different degrees of esoteric knowledge, and secrecy was paramount.

Syncretic movements have arisen, blending indigenous and Christian elements. Among these are Ok Bembem (1974–75),a A spirit-medium movement seeking contact with the dead; and 2) Rebaibal (1978–79), a A Christian revival led largely by women mediums possessed by the Holy Spirit. It promoted gender reconciliation, Christian ethics, and the destruction of men’s cult houses (except Telefolip). Today, belief in God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit coexists with enduring respect for Afek and fear of Magalim, often reinterpreted as a devil figure.

Death: Traditionally, bodies were exposed on raised platforms, with warriors’ bones later retrieved as relics. The Australian administration outlawed exposure burials in the 1950s; now the dead are interred in cemeteries. Pagans were believed to go to the underworld, while Christians ascend to heaven.

Ceremonies and Healing: Major rites revolve around male initiations once held at Telefolip, now revived after a hiatus. Christmas is widely celebrated, coinciding with the return of mine workers from Ok Tedi. Minor illnesses are treated with nettles, warm stones, and dietary taboos. Serious sickness is often attributed to sorcery, taboo violation, or spirit attack — either by Magalim or the Holy Spirit. Diviners and female spirit mediums diagnose and prescribe treatments, often involving prayer and behavioral change. Rural aid posts and Baptist clinics provide basic health care, while complex cases are sent to the government hospital.

Architecture and Art: Telefol architecture is notable for its carved amitung doorboards and painted shields, which are decorated with intricate symbolic motifs. Men’s and women’s houses, as well as ceremonial buildings, are often adorned with these carvings. Although figurative sculpture is rare, artistic expression is rich and highly symbolic. Women’s bilums (string bags) are also valued for their craftsmanship.

Telefolmin Door Boards See: ART FROM THE HIGHLANDS OF NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Telefol Society, Family and Marriage

Youths using hand drums (ot) during the otban, Oceanic Art Society

Telefol society is egalitarian, traditionally organized around ritual knowledge rather than wealth or rank. Leadership once rested with influential men (kamookim), but authority was minimal. There were no hereditary chiefs, and intragroup warfare was forbidden — though the Telefol collectively fought external enemies, notably annihilating the Iligimin in the 19th century and later engaging in raids against the Untoumin and Miyanmin until pacification in the 1950s. Today, the Telefol participate in local and national politics through elected village councillors and provincial representatives, though village governance remains informal and consensus-based. Social control depends on shame, tact, and the fear of sorcery rather than coercion. Disputes are resolved through avoidance or quiet mediation. [Source: Dan Jorgensen, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Telefol domestic units consist of nuclear families, often paired into joint households with two hearths. Land and resource rights are maintained separately by each family. Marriage traditionally occurred through sister exchange, accompanied by small bride-wealth payments in shells and pork. Today, cash bride-wealth (several hundred to several thousand kina) has replaced most shell exchanges. Residence is virilocal, with newlyweds living near the husband’s kin. Divorce is relatively easy and common, and custody of children is usually divided between parents. Children inherit land bilaterally from both parents, and both men and women hold independent land rights, maintained through continual cultivation.

Kinship follows an Iroquois-type system, distinguishing between parallel and cross-cousins and between patrilateral and matrilateral kin. Siblings are classified by sex and seniority, and cousin terminology is complex. Ritual moieties (Taro and Arrow) exist alongside kin ties but function independently.

Telefol Villages and Economic Activity

Villages range from 60 to 300 residents, averaging around 200. Settlements combine permanent village centers with dispersed garden houses, reflecting a two-tiered system of residence. Traditional men’s houses served as ritual centers, now largely replaced by churches as community hubs. Telefolip remains the primary surviving cult site. Houses are built on piles with thatched roofs and earthen floors containing two hearths. Clay hearths and split-bamboo walls are typical; fences and houses use similar construction methods. [Source: Dan Jorgensen, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

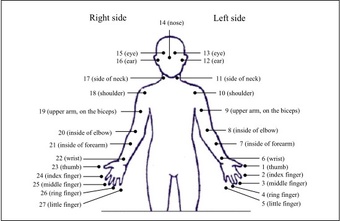

Telefol possess one of the world’s most unusual body-based counting systems, operating on a base-27 structure. Counting proceeds from the left pinky (1) across the body to the nose (14) and then mirrors the process on the right side to the right pinky (27), incorporating fingers, limbs, facial features, and joints in a fixed sequence.

Traditionally, Telefol subsistence was based on swidden (slash-and-burn) horticulture of taro, bananas, pandanus, sweet potatoes, and cassava, supplemented by pig husbandry, hunting, and forest gathering. Pig raising is central to social and economic life. In the past, exchange systems involved shell valuables used in bride-wealth and mortuary payments, as well as limited interethnic trade with neighboring Min groups such as the Faiwolmin and Atbalmin.

Since the 1980s, many Telefol men have worked at the Ok Tedi mine in Western Province, which brought wage labor, new technologies, and a cash economy. Pork sales are now an important income source, particularly for women and older people. Attempts at cash cropping (coffee, chili) have met with limited success due to poor transport access; the region remains largely isolated, with few reliable roads.

Mian People

The Mian people live in the mountainous interior of northwestern Papua New Guinea in Telefomin District, Sandaun (West Sepik) Province, and parts of Ambunti District, East Sepik Province. Also known as Miyanmin, Mianmin and Blimo, they are primarily shifting cultivators and hunters. Their villages are scattered through the Donner, Thurnwald, and Stolle mountain ranges at elevations around 1,000 meters (3,930 feet), as well as in nearby lowland valleys along the Upper Sepik, August, and May rivers. These rugged, rainforest-covered lands are accessible primarily by foot, a factor that has helped preserve traditional Mian culture, subsistence patterns, and social structure. The region has heavy rainfall and a variety of forest types ranging from lowland rainforests to mid-montane beech and conifer forests. [Source:George E. B. Morren, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Mian population in the 2020s was 2,600. The Mian speak Mian (also called Mianmin or Wagarabai), a Papuan language of the Mountain Ok subgroup of the Ok family. The dialect spoken in lower-altitude regions is known as Wagarabai. Mian society is divided between two main cultural groups: Am-nakai (“house people”) – southeastern, mountain-dwelling groups considered “cultured.” Sa-nakai (“forest people”) – northwestern, low-altitude groups considered “wild.”

History; Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that people have lived in the Mountain Ok region for at least 15,000–17,000 years, with agriculture emerging around 3,500 years ago. The Mian and their neighbors—the Telefol, Atbalmin, and others—trace their origin to a common ancestress named Afek. Traditional warfare included cannibalism, raiding, and abductions. Social control relied on public opinion, elder consensus, and shamanic intervention in severe cases. Intergroup violence often led to the fission of parishes or short-term territorial losses. In modern times, government law and mission influence have reduced armed conflict, though disputes over land and resources remain.

The first recorded Western contact came during the German Sepik River Expedition (1912–1914) led by Richard Thurnwald. Sustained interaction began in the 1950s with Australian colonial pacification, missionization, and the spread of introduced diseases, which heavily impacted local populations. By the 1960s, several Mian groups began a modernization program that included airstrip construction, schools, and medical posts—initiatives later extended across the Mountain Ok region. Since Papua New Guinea’s independence in 1975, the Mian have engaged in regional political movements like the Pan-Min initiative of the Mountain Ok peoples, particularly concerning land rights and mining developments. Many Mian now work as laborers or receive education through mission or government schools, with a growing number trained in teaching, health, and administration.

Mian Religion, Society and Family

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 95 percent are Christians, primarily through Baptist missions, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent, though traditional beliefs persist among elders. The creator figure Afek (or her sister) was believed to have shaped the world, including humans, animals, and the land of the dead. Spirits and bush demons were thought to inhabit rivers, trees, and natural places, causing illness or punishing taboos. The Mian also recognized a rainbow serpent associated with warfare and aggression. Ritual specialists included shamans (“death seers”) and elders who conducted initiation, mortuary, and curing ceremonies. Christianity has largely replaced older rituals. Cult houses were replaced by churches, and Sunday worship and baptism by immersion are now common. [Source:George E. B. Morren, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Mian society is traditionally egalitarian, emphasizing sharing and cooperation among kin and neighboring parishes. Each parish functions as an autonomous political and ceremonial unit. Leadership follows the big-man system, with prestige based on personal ability in gardening, hunting, ritual knowledge, or mediation. Am-nakai parishes sometimes ally militarily, historically fighting the Telefol and Atbalmin or raiding lower riverine peoples.

Family and Kinship: The nuclear family—husband, wife, and children—remains the basic economic and residential unit. Most marriages occur by mutual consent; sister-exchange is common. Polygyny exists but is socially modest, often due to practical needs rather than prestige.Residence is flexible (bilocal), with couples moving between the husband’s and wife’s kin groups.Divorce, once rare, has become more frequent in modern times. Inheritance is bilateral (from both parents). The Mian follow a Hawaiian kinship system in some contexts—grouping all same-generation relatives as “brothers” or “sisters”—but also use Iroquois-style distinctions for parental siblings and cousins.

Mian Villages, Art and Economic Activity

Parishes range from 40 to 200 members and control extensive territories, though only parts are occupied at a time. Settlements are small hamlets composed of: Men’s houses (for sleeping, meetings, and ritual use), Women’s houses (for families and domestic life) and Cult houses (for ancestral bones and ritual objects, now largely replaced by churches). Traditional houses are raised on posts with bark walls and thatched roofs. Modernization has led to large airstrip settlements such as Mianmin (Hak Valley), Yapsiei (Upper August River), and Hotmin (May River), where schools, health posts, and trade stores are concentrated.

The Mian maintain a flexible gendered division of labor: men handle clearing and construction; women plant, harvest, and prepare food. Women and children often assist in smaller hunts and collect edible plants. Fishing is also practiced. Taro is the staple (“taro is our bones”), supplemented by sweet potatoes, sago, bananas, yams, beans, pumpkins, pineapples, sugarcane, papayas, and breadfruit. Around airstrip settlements, introduced crops like tomatoes, peanuts, cabbages, and coconuts are grown both for food and small-scale trade. Domesticated pigs provide meat and hold ritual and economic value.

Artistic expression appears in body decoration—paint, feathers, fur, flowers, and cane—as well as in the design of utilitarian objects. Men carve tools, weapons, and ornaments, while women craft woven bags (bilums), mats, and bark cloth.

Gnau

The Gnau are a small linguistic and cultural group living on forested mountain ridges between the Nopan and Assini rivers in the Lumi area of West Sepik Province. Their villages lie within dense tropical rainforest at elevations around 300 meters (1,000 feet). The region is hot and humid, with a dry season from November to March and an average annual rainfall of about 250 centimeters. The name “Gnau” comes from the word for “no” in their language—a convention often used by linguists to name languages in Papua New Guinea. While united by a common tongue, the Gnau do not view themselves as a single ethnic group; identity is primarily village-based and relational, extending only to settlements personally known to an individual. [Source: Nancy E. Gratton, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 ~]

Language and Population: Gnau belongs to the Wapei branch of the Torricelli family of Papuan (non-Austronesian) languages, related to Olo (Wape) and other nearby tongues. Most men and boys, and many women, are bilingual in Tok Pisin, used for regional communication. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 2,700. Their population was estimated to about 980 in 1981.

History: Before European contact, Gnau villages were largely isolated and did not participate in the regional trade networks that linked many neighboring groups. Relations between villages were often hostile. Before colonial pacification, intervillage warfare was common and a source of prestige. Battles were usually fought village against village, not through large alliances, and were motivated more by honor than by economic necessity—land and resources were abundant. In the 1930s, Australian recruiters began hiring Gnau men for two-year labor contracts on coastal copra plantations. Though World War II brought little direct fighting to the area, returning plantation laborers became key agents of change afterward. Peace after the 1950s brought stability and expansion of garden lands.

An Australian patrol post was established in 1949, and by the mid-1950s government efforts had largely ended intervillage warfare. Peace allowed for territorial expansion, increased gardening, and improved inter-village relations. Christian missions soon followed: a Franciscan mission in 1951 and a Protestant mission in 1958. These introduced schools, an airstrip, stores, and a hospital. By 1957 the Gnau were paying taxes, and in 1964 they began voting for members of Papua New Guinea’s National Assembly. These developments gradually integrated the Gnau into the national economy and political system.

Religion: Today most Gnau identify as Christian, but traditional cosmology remains embedded in local songs, myths, and agricultural ritual. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 90 percent are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being to 10 to 50 percent. Illness is attributed mainly to taboo violations. Treatment combines herbal remedies, bloodletting, and ritual observance. Shamans and elders perform spells and dietary restrictions to restore health.

Traditional belief links each ancestral founder to specific sites within Gnau territory, leaving behind ritual knowledge and “proper ways of living.” These myths describe numerous spirits invoked in garden rituals for successful crops. Every man learns ritual lore, with the mother’s brother acting as ritual mentor during a boy’s initiations. Magical power, especially to cause death, was once believed to be inherited through this maternal line. The major male initiation rite, the Tambin, marks a boy’s passage to manhood. Led by the mother’s brother, the ceremony involves seclusion, feasting, and ritual bleeding from the mouth and penis—symbolic of purification and maturity. Girls undergo a parallel, though less elaborate, puberty rite. Upon death, corpses were traditionally smoke-dried on platforms before burial became common. The dead are believed to watch over descendants and communicate through dreams. Gnau songs and dances are highly developed, accompanied by slit drums. These performances preserve mythology and play a central role in major ceremonies.

Gnau Society and Life

Gnau society is organized around two principles: 1) Locational attachment to birthplaces of individuals and their ancestors. And 2) Patrilineal descent through the male line, which structures villages into hamlets and sub-hamlets. Villages historically had no formal political offices or centralized authority. Leadership derived from age, kinship, personal prestige, and skill in mobilizing others, especially during warfare. Since the 1960s, elected councillors and national representatives have provided new forms of political linkage beyond the village. Social control traditionally relied on taboos, fines, and fear of sorcery. A mother’s brother was believed to hold mystical power over the health and fate of his sister’s children, enforcing cooperation between affinal groups.

Marriage and Family: Gnau domestic life is divided: men sleep in men’s houses, while women live in separate dwellings with their children. The family is thus defined less by co-residence than by daily cooperation in food preparation and garden work. Descent groups are exogamous, but villages often contain members of several groups, allowing internal marriage. Marriages are arranged between families, with bridewealth paid after the birth of the first child—confirming the union and transferring rights over children to the father. The mother’s brother retains important ritual obligations, especially in children’s initiation rites. Adultery requires compensation to the offended husband, and widowers are expected to remarry. Widows often prefer not to, to protect inheritance rights for their children.

Kinship and Descent: Descent is patrilineal, and genealogies can extend five to fifteen generations—an unusually deep reckoning for the region. Land and ritual lore belong to lineages and are inherited from father to son. Women do not inherit land or ritual rights. Kinship terminology emphasizes brotherhood and seniority among men of the same generation descended from a founding ancestor. These distinctions also shape respect and ritual obligations.

Villages are built on hilltops—about 300 meters above sea level—reflecting a historic need for defense. Each village contains multiple named hamlets surrounded by coconut palms, with gardens in the valleys below. Houses include: 1) Men’s houses (for sleeping and meeting); 2) Women’s dwellings (for wives and children); and 3) Day houses (for communal meals and work). Substantial huts are also built near gardens for temporary stays during cultivation periods.

Agriculture, Hunting and Economic Activity: The Gnau live in a lush lowland rainforest zone and practice shifting horticulture, hunting, and gathering. Traditionally, sago was the staple food, but today it is supplemented by taro, yams, sweet potatoes, corn, bananas, pawpaw, pitpit, breadfruit, beans, coconuts, and sugarcane. sources: Hunting targets include pigs, wallabies, cassowaries, birds, and reptiles. Fishing is done with nets or plant poison. Eggs, insects, and grubs are also gathered. A household may maintain up to six gardens at once, integrating horticulture with hunting and foraging cycles. Gnau material culture is largely utilitarian. They traditionally made stone axes, bows, nets, baskets, net bags (bilums), skirts, ornaments, traps, and wooden containers. Feather and shell decorations are worn for ritual events. Clay pots were once made but have largely disappeared.

Men traditionally hunted, built, and cleared land while women gathered water, firewood, and prepared food. Both sexes fish and collect wild foods. Men sometimes work for wages on coastal plantations or government projects, though the Gnau remain relatively isolated economically. Rice is grown mainly as a cash crop; most consumer goods now come from local mission stores.

Bimin-Kukusmin

The Bimin-Kuskusmin (often referred to simply as Bimin) are an Indigenous group inhabiting the rugged, mountainous interior of West Sepik (Sandaun) Province near the borders of Western Province and Papua’s highland regions. Villages are typically small, consisting of clustered hamlets connected by forest trails. Subsistence is based on gardening, hunting, and gathering, supplemented by trade with neighboring peoples. The Bimin lived in relative isolation until the mid-20th century and continue to maintain many traditional cultural practices. European contact with the Bimin began only in the late 1950s, and the spread of Western goods and technologies has been gradual. Despite these changes, many traditional institutions and symbolic systems remain integral to community life.

Bimin society is divided into four primary clans: Bim, Kuskis, Kasan, and Kuel. The Bim and Kuskis clans dominate the main valley area known as Bim Weng. The Kasan and Kuel clans are concentrated in Nimtew Weng. Clan affiliation determines marriage, land rights, and ritual participation. Social life is centered on kinship, reciprocal exchange, and shared participation in ceremonies.

Bimin Language belongs to the Ok branch of the Trans–New Guinea language family, closely related to Faiwol and influenced by neighboring groups such as the Oksapmin. The estimated number of native speakers ranges from 2,300 to 4,300, depending on the source. Dialectal variation exists, particularly in Nimtew Weng, where a local form is spoken. Like other Ok languages, Bimin features dyadic kinship terms (expressing relationships between pairs of people) and a distinctive numerical system.

Religion: According to the Joshua Project, approximately 90 percent of the Bimin population identifies as Christian, though many Christian practices coexist with traditional cosmological beliefs. An estimated 10–50 percent identify as Evangelical Christians. Bimin-Kuskusmin cosmology centers on a complex theory of procreation and life-force that informs concepts of personhood, gender, and mortality. Core symbolic elements include bone, bone marrow, and the finiik (spirit essence). These symbols underpin ideas of cyclical regeneration, linking birth, death, and ancestral continuity. Reality is conceived as monistic, with the spiritual and physical realms forming an integrated whole.

Cannibalism: Among the Bimin-Kuskusmin, ritual consumption of human remains was historically practiced as part of funerary ceremonies rather than as a form of sustenance. Different body parts were symbolically assigned gendered properties: bone marrow (male substance) and fat (female substance). Male descendants consumed marrow to inherit the deceased’s vitality, while female relatives partook of fat to promote fertility. Anthropologist Fitz John Porter Poole emphasized that such acts were deeply ritualized and spiritually charged, not motivated by hunger or aggression. Participants often described the practice as emotionally distressing rather than desirable.

Sexuality and Child Development: Ethnographic research by Fitz John Porter Poole (1981–1990) among the Bimin-Kuskusmin explored how child-rearing practices, gender formation, and spiritual development are interlinked within their cultural model of procreation. Mothers are responsible for nurturing both the physical and spiritual growth of their sons. This includes ritualized forms of tactile care believed to stimulate healthy development and ensure balance in the child’s finiik or life-force. These acts are publicly regulated, with social norms and ritual protocols designed to prevent impropriety. Elder women often supervise younger mothers to ensure these customs are carried out correctly. Girls are initiated at menarche, typically around ages 17–18, through ceremonies emphasizing fertility, modesty, and community recognition. Premarital virginity is culturally esteemed, and marriages are generally arranged, often before puberty but requiring the girl’s consent. Poole’s analysis interprets these practices not as expressions of sexual behavior in the Western sense but as part of a symbolic pedagogy through which bodily growth and spirit are harmonized, ensuring the reproduction of personhood and social order.In his landmark study “Symbols of Substance: Bimin-Kuskusmin Models of Procreation, Death, and Personhood” (1984, The Australian Journal of Anthropology), Poole presents the Bimin worldview as a coherent symbolic system linking substance, spirit, and society. His work remains one of the most detailed ethnographies of the Ok-speaking peoples and a major contribution to the anthropology of Melanesia. [Source: D.F. Janssen, Growing Up Sexually, Volume I. Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, 2004]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, University of Surrey

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025