Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups / Arts, Culture, Sports

LOWER SEPIK REGION AND ITS ART

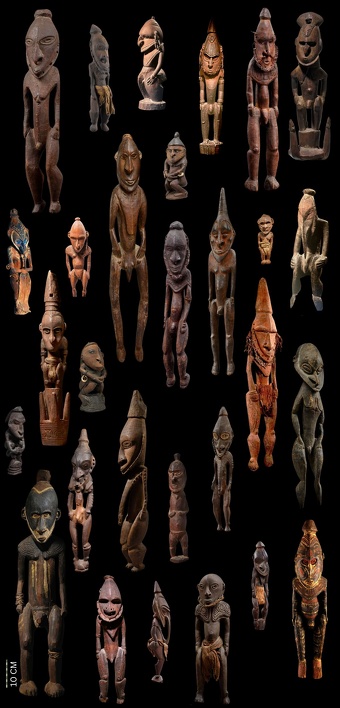

Male and female miniature figures, Lower Sepik or Coastal Region, 19th to early 20th century, wood, plaitwork, red ochre, De Young Museum

The Sepik is the longest river on the island of New Guinea. The majority of the river flows through the Papua New Guinea (PNG) provinces of Sandaun (formerly West Sepik) and East Sepik, with a small section flowing through the Indonesian province of Papua. The Sepik River winds lazily through the swampy rainforests of northwestern Papua New Guinea. has a large catchment area, and landforms that include swamplands, tropical rainforests and mountains. In many places it is a placid, almost lake-like river. [Source: Wikipedia]

Roughly a dozen Sepik languages are spoken in the Sepik River area. Each one corresponds to one or more culture regions of related villages that exhibit similar social characteristics. The largest language and culture group along the river is the Iatmul people. The Sepik-Ramu basin is home to the Torricelli, Sepik, Lower Sepik-Ramu, Kwomtari, Leonhard Schultze, Upper Yuat, Yuat, Left May, and Amto-Musan language families, while local language isolates are Busa, Taiap, and Yadë. Torricelli, Sepik, and Lower Sepik-Ramu are by far the three most internally diverse language families of the region.

The Sepik is famous for its colorful ethnic groups, spirit houses, wood carvings and rain forests. It is one of the most profuse and diverse art producing regions of the world. The numerous different tribes living along the river produce magnificent wood carvings, sculpture, masks, shields, clay pottery and other art and craft. Many tribes use garamut drums in rituals; the drums are formed from long, hollowed-out tree trunks carved into the shape of various totem animals. The colorful spirit houses vary from village to village. They are a place where men hang out, smoke and make music. Women aren't even allowed to walk on the paths that lead to them and the men feel if a woman enters the house it will anger the spirits which are believed to live in the jungles and mountains. Carvings of spirits can be found both outside and inside the spirit houses. According to Lonely Planet the best houses are in Mapril. Different areas along the Sepik produce distinct art styles.

On a mid-20th century house post from Lower Ramu River region of the Lower Sepik made of wood, fiber, shell, paint, feathers, plastic and metal , measuring 16 feet 2 inches inches high, with a width of 14 inches and a depth of 10 inches (492.8 × 35.6 × 25.4 centimeters), the Metropolitan Museum of Art says: The widespread exchange of ritual paraphernalia such as masks and figures throughout the Lower Sepik region has resulted in a rich cross-fertilization of artistic styles. Indeed, though this housepost was collected in the Ramu River area, the treatment of the human figure and motifs employed suggest the artist came originally from the Murik Lakes or was strongly influenced by Murik techniques and iconography. Art in the Lower Sepik region centers on the representation of important ancestors and spirits. The supporting posts of ceremonial houses, such as the present work, are richly decorated with depictions of the ancestors, spirits, and sacred masks associated with the house. Representations of spirits frequently have long beak-like noses, which evoke the heads of totemic birds, while the noses of human ancestors are more naturalistically rendered. Images of both ancestors and spirits as well as depictions of sacred masks can be seen on this housepost.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEPIK RIVER GROUPS: WHERE THEY LIVE, ART, SPIRIT HOUSES, CROCODILES ioa. factsanddetails.com

KWOMA (A SEPIK RIVER TRIBE): HISTORY, LIFE, ART ioa. factsanddetails.com

EAST (LOWER) SEPIK PEOPLE — BOIKEN, MURIK, SAWIYANO — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

ABELAM AND ARAPESH OF THE SEPIK RIVER: LIVES, HISTORY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE: MASKS, FIGURES AND SHELL RINGS ioa. factsanddetails.com

BIWAT (MUNDUGUMOR): LIFE, RELIGION, FAMILY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

IATMUL PEOPLE OF THE SEPIK RIVER: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHAMBRI: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CROCODILE MEN AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

WEST SEPIK HIGHLANDS PEOPLE — WAPI, TELEFOL, MIAN, GNAU, BIMIN — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

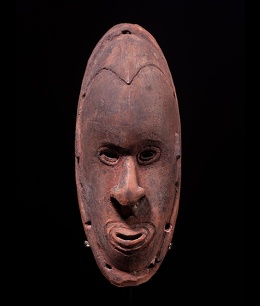

Masks from the Lower Sepik Region

Masks from the region around the Sepik River in New Guinea, dating to the late 19th century, are among the most sought-after art objects from Melanesia. A Brag Sebug mask from the Murik Lagoon in the lower Sepik region, 19½ in (49.5 centimeters) in height, sold for around US$75,000 at a Christie’s auction in Paris in June 2020.

A late 19th-early 20th century flute mask made of wood, paint, fiber and seeds by the Kopar people of the lower Sepik region is 15.6 feet (4.76 meters) tall. The Kopar people, who live along the lower reaches of the Sepik River. Masks like this one, lacking eyeholes and with a shallow, concave back far too small to accommodate a human face, served as ornaments for sacred flutes.

One mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was probably created by the Romkun, Breri, or Igana peoples of the Ramu and Guam Rivers, whose masking traditions are largely undocumented. Dating to the 19th century, it was made from wood and is 23.75 inches high, with a width of 9.5 inches and a depth of 5.5 inches (60.3 × 24.1 × 14 centimeters). The pierced eyes and small holes on its periphery, probably used to secure it to a larger basketry headdress, indicate it was likely a dance mask.

A mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art made by the Bungain people in the early 20th century is fashioned from wood and paint and is 18 inches and long and 6 inches deep (45.7 × 15.2 centimeters). A mask made by

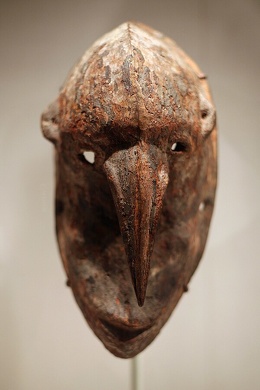

Types of Masks from the Lower Sepik Region

Masks with extremely long and thin noses occur widely throughout the lower Sepik region, where they are predominantly depictions of powerful spirits. Carvers among the Murik people state that these elongated noses are explicitly modeled after the beaks of birds. These beak-shaped noses find their supreme expression in the Kopar masks in which the facial features are almost entirely condensed into an enormous spikelike nose, with a small oval eye on either side. Some examples are crowned, as here, by a small bird, possibly an eagle, which may represent a totemic species.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Masks and figures from the peoples of the middle Ramu and Guam rivers are characterized by faces whose features, rendered in relief, are fully or partially bracketed by a nested series of hooklike forms. They share a number of stylistic features, most notably the large diamond-shaped eyes, with the dance masks of the neighboring Kominimung people, whose language and culture are related to those of the other three groups. Hence, it is possible that the dance masks of all four cultures had similar imagery and functions. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007] Eric Kjellgren is a leading scholar of the arts of Oceania. Formerly curator of Oceanic Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and director of the American Museum of Asmat Art (AMAA) and Clinical Faculty in Art History at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, he has worked extensively with contemporary Indigenous Australian artists and done field research in Vanuatu]

Dance masks among the neighboring Kominimung people have similar imagery and possibly served similar functions. Worn by initiated men during ritual performances, Kominimung dance masks depict bwongogo, ancestral spirits responsible for the success of important activities such as gardening, hunting, fishing, and formerly, warfare. Women and children are not allowed to witness the creation of the masks. However, the entire community may watch the performance of the masked dancers.

Uses of Masks from the Lower Sepik Region

In the Sepik region, masks were not always made to be worn on the face. Many Sepik peoples created masks, or masklike carvings, that were never worn but served, like figures, as sacred images of ancestors and spirits and were kept in the men 's ceremonial house. In many areas miniature masks were made to adorn sacred flutes or to be worn as personal ornaments. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Among the Kominimung, both masks and figures depict ancestral spirits called bwongogo, whose form is made visible to the human world through sculpture. There are many types of both male and female bwongogo, and the spirits are responsible for promoting the success of important activities, such as gardening, hunting, fishing, and, formerly, warfare.

Worn by initiated men as part of ritual performances, each mask depicts a particular ancestral spirit associated with one of the village clans. Women and children are not allowed to witness the creation of the masks, which are carved by the men in secluded locations outside the village or within the fenced-off grounds surrounding the men's ceremonial house. However, all members of the community are permitted to see the performance of the masked dancers.

Lewa (Masks)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Spirits associated with the village and the forest lie at the center of the artistic and ceremonial life of the peoples of the Schouten Islands, a small offshore archipelago just west of the Sepik River delta, in northern New Guinea. Many types of spirits can only be heard, their voices manifest as the sounds produced by sacred flutes, bullroarers, whistles, or bamboo trumpets played by the village men. The spirits known as "village lewa," however, make themselves visible to the community in the form of masked dancers (tangbwal) who enforce ritual prohibitions during the lead-up to walage, ceremonial distributions of food made by the village headman. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Some months prior to the walage, the headman summons the village lewa from the world of the spirits. The first to appear is a female lewa, portrayed by a man in a bulky costume made from women 's skirts, who "rises out of the sea" and walks into the men's house, imitating the movements of a heavily pregnant woman. In the men's house this female lewa "gives birth" to sons, typically twins, who emerge from the house the following morning.

Each headman owns a pair of wood masks, also called lewa, which represent the twin sons. The two male lewa perform together, each wearing a lewa mask as the central element of an elaborate costume embellished with shell and feather ornaments and worn with an enormous conical headdress and bushy garments of sagopalm leaves, which conceal the performer's body. Although the Lewa spirits are said to be mute, each carries a shell rattle, whose sound accompanies his movements, as well as a spear. Thus arrayed, the lewa appear in the early morning and dance continuously until nightfall, the roles of the spirit brothers being assumed in turn by a series of dancers, who don the elaborate costumes when the preceding performers become exhausted. The conclusion of the dance is followed b a ceremonial meal, which signals the beginning of a prohibition on the harvesting of all ripe coconuts in the community.

During the three to four months required for a sufficient quantity of coconuts to ripen for the walage ceremony, the masked lewa dancers periodically reappear, patrolling the groves and gardens, ostensibly to enforce the ban but also to amuse themselves b playfully frightening the women and children at work in the fields.

Delegations from nearby villages also visit, and pairs of guests are invited to don the masked costumes and perform the lewa dance.Once all the coconuts necessary for the walage have ripened, the lewa are sent back to the land of the spirits, accompanied by funerary chants and lamentations. A long, narrow platform is constructed at the edge of the village, which serves as a metaphorical canoe (kat) to carry the lewa on their homeward journey.

The lewa proceed to the kat and dance, after which the masked costumes are removed and placed over cane frames, which serve as makeshift mannequins.' The lewa mannequins are displayed within the canoe for two or three days, after which the costumes are dismantled and the masks returned to the headman for safekeeping until it is time to summon the lewa once again.15 While the lewa are primarily associated with the walage, the headman can also call upon them to appear on other occasions, such as the inauguration of a new men's house or trading canoe or the life-passage rites of his children. Stripped of their ceremonial accoutrements, lewa masks remain powerful works of sculpture whose smoothly contoured features combine to form striking images of the spirits they portray. The prominent nose, as here, is accented by a distinctive spiral ornament, modeled after the shell nose ornaments worn by local men. The holes that appear on the periphery of this mask served for the attachment of the elaborate dance costume.

A mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made by the Wogeo or Barn people of the Schouten Islands of lower Sepik region, Dated to the 19th-early 20th century, it is made of wood and paint and is 15 inches (38.1 centimeters) high. A 1934 photograph shows a pair of masked lewa dancers performing at Gol, on Wogeo Island, in the Schouten Islands. The features of the mask were accented with white paint.

Shields from the Lower Sepik Region

Dating to the late 19th-early 20th century, one shield in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection originates from Kanduanum village, Lower Sepik River and was made by the Angoram people from wood, paint, fiber and is 64.5 inches high, with a width of 24 inches and a depth of 10 inches (163.8 x 61 x 25.4 centimeters). [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Carvers from the Angoram and Biwat peoples living in the area around the junction of the Yuat and Sepik rivers produced a similar variety of war shield, characterized by a central column of three to six superimposed faces, whose eyes are often surrounded, as here, by bristly, upwardcurving projections.1 The painted and carved designs were often further accented with fiber tassels attached to the edges of the shield or threaded through the pierced noses of the images. 2 In former times shields of this type were reportedly used in battle to protect the owner from spears. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

According to Beta Omang, a Biwat man from Akuran village, the faces on the shields depict Ra ram, a powerful spirit, and the bristlelike elements around the eyes represent spears (damvro). Another type of face with round eyes, which appears at the top of some shields, represents the ftying fox, a large species of fruit bat. The imagery of the present Angoram shield is closely similar to that of the Biwat example described by Omang. Although there is no precise information on the interpretation of shield imagery among the Angoram, it seems reasonable to suppose that the present work depicts the same, or similar, beings that appear on Biwat shields. Given the hazards and uncertainties of combat, the addition of such powerful spirit images to war shields may have been intended to afford the bearer an added measure of supernatural protection.

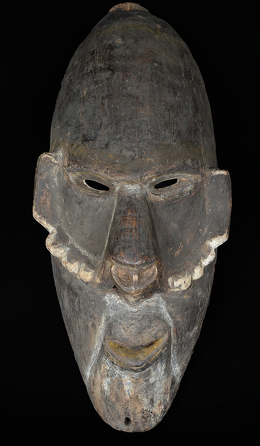

Masks of the Boiken People

Describing a 19th century, 14-inch (35.6-centimeter) -high wooden mask made by coastal Boiken people of the lower Sepik region, Eric Kjellgren wrote: Depicting a variety of male and female spirits, masks among the coastal Boiken were known as wale or ware. In former times such masks appeared in dances held as part of religious ceremonies. The masks were not worn directly on the face; they were instead attached to a framework of cane, which was placed over the dancer's head and supported on the shoulders. The dancer's costume was completed by brightly colored grass skirts that extended to the knees. When not in use the masks were removed from the costumes and preserved in the men 's ceremonial house. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

A typical ceremonial house might contain twenty masks made from wood or woven reeds, which were preserved along with other sacred objects, such as flutes, bull-roarers, and human skulls.3 In coastal Boiken ceremonial houses, men reportedly stored their spears, used in hunting and warfare, next to the masks, whose supernatural power presumably infused the weapons, ensuring success.

According to coastal Boiken oral tradition, the first wale were made by a man named Pantjapong. A group of women, the story goes, heard the sounds of spirits who were living underwater, and the village men set out to discover the source of the sound. After unsuccessfully probing the waters with poles made from sago palms, Pantjapong decided to dive in and see for himself. Swimming beneath the surface, he came upon the spirits, who were wearing large masks. When he returned to the village, the other men asked him to carve masks like those he had seen, and these became the original wale.

In historic times, as masks decayed and needed to be replaced, the members of the men's house commissioned an artist, called a duo wale nare sugo, to produce a new wale. As payment, the artist was provided with all his meals while he worked and with a final feast when the commission was complete. The finished masks were kept and reused for many years and were periodically repainted to refresh their colors for important ceremonies. Bearing the traces of many layers of paint, this work shows evidence of a long history of use. Its eyes and nose twisted slightly askew, the spirit gazes back at the viewer with an expression at once inquisitive and subtly menacing, perhaps as a reminder that the powers of the spirits are equivocal, able either to help or to harm.

Art of the Biwat People

The Biwat live in the area of the central Yuat River in East Sepik Province. Also known as the Mundugumor and Mundokuma, they speak the Biwat (Mundugumor) language and Melanesian Pidgin. "Mundugumor" is an old name relating to their art styles. The Biwat refer to themselves as "Biwats," the name of one of their villages as well as the name sometimes given to the Yuat River. The Biwat language belongs to the Yuat family.[Source: Joshua Project; Wikipedia]

Biwat art was primarily sacred in purpose, aiming to influence supernatural forces. Sculpture and painting predominated, showing stylistic influence from the Middle Sepik artistic tradition.Eric Kjellgren wrote: Biwat art is particularly remarkable for the delicacy and virtuosity of its intimately scaled wood carving-primarily personal ornaments worn in the hair or attached to the belts and armbands of dancers. Likely worn as an element of festive or ceremonial attire, this hair ornament has an unadorned, pinlike base, which would have been inserted into the wearer 's coiffure. Some sources, however, state that such hair ornaments were intended not to adorn the human head but rather to be inserted among the ornaments that decorated the heads of flute-stopper figures. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

One Biwat hair ornament in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection comes from the Yuat River area of the lower Sepik region. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of wood, paint and is 15 inches (40.3 centimeters) tall. Many Biwat ornaments were used interchangeably to adorn flute stoppers or the human body, so it is possible that the hair ornaments served both functions. Nonetheless, the size of the surviving hair ornaments, often nearly as tall as the flute stoppers themselves, suggests that they served primarily for personal adornment. The form of Biwat hair ornaments, whose central elements are encompassed within a series of concentric hooks, is strikingly similar to that of the larger hook images produced by the Yimam people of the Korewori River, whose headwaters lie nearby, as well as those of the more distant Bahinemo people..

The peoples of the Sepik are linked by an elaborate network of exchange in which songs, ceremonies, and ceremonial objects circulate widely. Thus, it is possible that the diminutive hook figures on Biwat hairpins were inspired by Yimam objects-such as the smaller hook figures used by Yimam men as hunting charms-obtained through trade.

Biwat Masks

Biwat mask

The Biwat (Mundugumor) people of the Lower Sepik River are well-known for masks.Eric Kjellgren wrote: In the past, Biwat carvers produced numerous forms of masks. Although there is almost no information on the specific identity and uses of individual examples, masks, like other forms of sculpture, appear to have portrayed the two major types of supernatural beings in Biwat cosmology: maindjimi, or forest spirits, who lived in the woods surrounding the village, and saki, or water spirits, who inhabited rivers and other bodies of water. ' One Biwat mask likely represents a water or crocodile spirit. In the village of Kambrambo masks of this these pe appeared as the heads of human Iike figures who rode on the backs of gigantic effigies representing the "crocodile mother," who swallowed and later disgorged young novices as part of initiation ceremonies.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007. Eric Kjellgren is a leading scholar of the arts of Oceania. Formerly curator of Oceanic Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and director of the American Museum of Asmat Art (AMAA) and Clinical Faculty in Art History at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, he has worked extensively with contemporary Indigenous Australian artists and done field research in Vanuatu]

Masks were also likely worn as part of other initiation rites. One mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made on a village on Yuat River in the lower Sepik region, by the Biwat people. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of wood, paint and fiber and is one foot (30.8 centimeters) tall. This piece is attached to an armature of cane, which fitted over the head to hold it in place. Beyond their role as ceremonial regalia, some Biwat masks were venerated as sacred objects in their ownright, forming part of a broader category of supernaturally powerful items, such as flutes, which could be viewed only by the initiated.

Flute Stoppers of the Biwat People

Eric Kjellgren wrote: In many regions of New Guinea, flutes, fashioned from hollow cylinders of bamboo ranging from a few inches to several yards in length, were among the most sacred and important of all ceremonial objects. Most forms were played in the manner of a Western flute, by blowing across a hole bored in the side of the instrument near the upper end. The tops of such side-blown flutes were often adorned with ornamental flute stoppers: wood figures carved atop peglike bases designed to be inserted into the upper end of the bamboo to provide a tight seal. In former times the most ornate sacred flutes and flute stoppers were those of the Biwat people ((Mundugumor), who live on the middle reaches of the Yuat River, a southern tributary of the Sepik. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The role of sacred flutes among the Biwat differed from that of flutes among other New Guinea peoples in several important respects.' In most New Guinea societies such flutes were exclusively male objects, commissioned and owned by clans or other kin associations, and use of the flutes-or even the knowledge of their existencewas restricted to initiated men. By contrast, Biwat sacred flutes were owned by individual men and their existence was known to all. The rites and initiations of which they formed a part were also sponsored by individuals and open to children of both sexes, and the flutes formed part of the dowries of wealthy young women when they married. The classic, and most common, form of Biwat flute stopper consists of a stylized human image with a small, thin body, stooped shoulders, and a greatly enlarged head, often, as here, depicted with an extremely high, domed forehead. The margins of the chin and cranium here are lined with rows of holes, which served for the attachment of hair and other ornaments.

A flute stopper in the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made by the Biwat along the Yuat River in the lower Sepik region. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century and made of wood and hair, it is 21 inches (54.9 centimeters) tall. This work once stood on a peglike base, now lost, which was inserted into the upper end of the f1ute. Although they depict human images, f1ute stoppers of this type formed part of the ornate f1utes known as ashin, which were associated with crocodile spirits. When a man wished to make a new ashin f1ute, he commissioned a carver, for whom he had to provide food throughout the carving process, to create the stopper.

A group of individuals, each contributing materials to adorn the stopper figure, then assembled in secret to decorate the f1ute in a ceremonial enclosure built on the riverbank. During the creation and adornment of the f1ute, a water drum, its sound representing that of the mother crocodile, who ceremonially gave birth to the flute, wa s played in the enclosure. Vast quantities of precious ornaments of shell, feather, bone, fiber, and other materials were attached to the f1ute stopper, encrusting it so thickly that often only the eyes of the stopper remained visible. The body of the f1ute was completely covered in cowrie shells. Many ashin f1utes were so heavily embellished that they were unplayable, and smaller, unadorned f1utes had to be played in their stead on ceremonial occasions. Once complete, the f1ute was ceremonially fed; food was offered to the stopper figure, the playing hole, and then to the stopper again before the assembled group was allowed to eat. The f1ute, now representing the "child of the crocodile spirit," was then brought forth and brief1y displayed to the entire community before being taken to the house of its owner.

Stood upright against the wall and carefully sheathed in mats, the f1ute was unwrapped periodically to be "fed " by the initiated or to be used in ceremonies. Ashin flutes played a central role in the rites known as the crocodile initiation, during which initiates crawled into the mouth of a large crocodile effigy and their bodies were cut by its "teeth" (that is, the cutting implements wielded by the initiators), producing permanent scarification marks on the skin.

A smaller flute stopper from Yuat River area was made by the Biwat or neighboring peoples in the late 19th-early 20th century. It is made of wood, paint, shell and is 8 inches (21.3 centimeters) tall. It is also likely from an ashin f1ute, retains its original peglike base. It is crowned by a fantastic hybrid figure with a bulbous head and prominent animal snout atop a robust male human body. A small lizardlike creature appears on the cranium. Although the identity of the being represented is unknown, the image is almost certainly that of a powerful spirit.

Figures from the Lower Sepik Region

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Working in a series of related traditions, the artists of the middle Ramu and Gu am rivers produce, or produced, similar types of anthropomorphic figures with flattened oval heads resembling masks and smaller, fully modeled bodies, whose trunks and limbs are often nearly cylindrical in form. Carvers from the Breri, lgana, Kominimung, and Romkun peoples produce both male and female images as well as a unique form of male figure that has only a single trunklike leg.' With the exception of those of the Kominimung, the nature and significance of these figures are largely unknown. Among the Kominimung the figures, like masks, portray individual bwongogo, ancestral spirits whose powers ensure the success of agriculture, hunting, fishing, and other human endeavors. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Figures among the Kominimung are men 's sacred objects, kept and used within the precincts of the men 's ceremonial house. Some, such as the one-legged images. can be seen only by men, while during ceremonies others are briefly raised above the fence that surrounds the men 's house, allowing women and children to catch a glimpse of the bwongogo. Any man may produce everyday objects, such as betel-nut-chewing equipment and other personal accessories, but figures and masks are typically made by skilled carvers, whose artistic talents are known and recognized in the community. As women and children are not allowed to witness the creation of masks or figures, Kominimung artists work in secluded spots in the forest outside the village or within the men 's house compound.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a figure from the Ramu or Guam River of the lower Sepik region probably made by the Breri or lgana people. Dated to the 19th or early 20th century, it is made of wood and paint and is 53 inches (134.6 centimeters) tall. When carving, artists often sit together in groups so they can talk and critique one another 's work. Despite the sacred nature of the images they are producing, a lighthearted atmosphere prevails, and the carvers often gossip and joke with one another to relieve the monotony of their task.-"If we crack jokes," the carvers say, "the work is light; if we don't, the work is heavy. Artists, nonetheless, take their work seriously, seeking to perfect the form and adornment of their individual creations. As Pita Mangal, a noted Kominimung carver, observed, "A woodcarver must concentrate, think well and be inspired. You must think hard which motif you want to cut in the wood. and you must feel this inside, in your heart.

On a 70-inch (1780centimeter) tall, 19th century figure from Keram River area of the lower Sepik region made of wood, feathers, cowrie shells and fiber, Kjellgren wrote: Boardlike images from which fully modeled heads and other features emerge to create anthropomorphic figures occur in a number of Sepik cultures. Collected in the Keram River region, this image has a long, spatulate body, whose form evokes, or perhaps represents, the blade of a large canoe paddle, from whose planar surface a face, arms, and phallus emerge to create a human image.' The original use and significance of the figure are undocumented. Like the majority of Sepik wood sculpture, however, this work was almost certainly a religious image depicting a powerful spirit or ancestor, which would have been kept, together with similar images and other sacred objects, in the men's ceremonial house of the village.

The ornate headgear and ornaments of the figure indicate that it likely depicts a person or supernatural being of particular importance. The jawline is embellished with cowrie shells, precious objects that served locally as both ornaments and ceremonial currency. The head is surmounted by what appears to be an elaborate headdress trimmed with cassowary feathers enhanced with additional cowrie shells. In its hands the figure grasps a long cylindrical object, which may represent a snake. Overall, the figure's lavish regalia strongly suggest that it was a sacred image that stood within a Keram ceremonial house, where living men, possibly similarly attired, honored the ancestors and spirits.

One late 19th-early 20th century figure made by the Kopar or Angoram people of lower Sepik region was fashioned from wood and paint and 25.4 feet (7.75 meters) tall. Created by an artist of the Kopar or Angoram people, who live on the banks near the mouth of the Sepik River, this figure almost certainly portrays a spirit. Its features are drawn out into a series of attenuated forms that combine to create a delicate openwork image, so that the figure, though hewn from solid wood, captures the wraithlike otherworldly qualities of the supernatural being it depicts.

Images of this type were carried or worn by performers during dances. Attached to short lengths of bamboo, which still survive on some examples, the figures were held in the h and as dance wands or, according to one account, affixed to a framework that was worn on the dancer's back during initiation ceremonies.' The conical knob on the head of the present figure once served for the attachment of a feather headdress, now lost. 2 As in the masks of the same region, the most dominant feature of Kopar/Angoram dance figures is the enormously elongated beaklike nose. The nose of this figure runs down the entire length of the body to below the feet, where it merges with the stylized head of a boar, on which the figure stands. 3 This figure once belonged to the Surrealist painter and writer Wolfgang Paa I en (1905-1959), who was perhaps drawn to it by its distinctive treatment of the human form. The tremendous virtuosity and plasticity with which artists from New Guinea and other regions of the Pacific reworked and remade the human image were greatly admired by the Su rrea I is ts, whose own works often i ncorporate imagery closely inspired by Oceanic art.

Art of the Murik People

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Living along the Murik Lakes, a series of coastal lagoons near the mouth of the Sepik River, the Murik people were, and remain, accomplished carvers and traders. Murik objects, exchanged with neighboring peoples as part of regional trade networks, may have been widely influential in the development of the broader tradition of lower Sepik sculpture. According to oral tradition, the Murik learned wood carving from Andena and Dibadiba, ancient culture heroes who descended the Sepik River in a canoe and taught the people both artistic and practical skills.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The art of carving is passed down only in certain families. A novice is apprenticed to his father or uncle, although he may afterward learn additional skills from other master carvers. Murik artists strive to achieve perfection in the symmetry and proportions of their works. Others in the community may express their approval or criticism of the carver's skills by describing a work as aretogo (beautiful) or moago (ugly) or by making statements such as tosiyan (it stands out well}. However, it is not the visual properties of the carved image but the supernatural power (maneng) imparted to it by the artist that is of foremost importance.

As Morakau, a carver from Darap village active in the 1970s, stated: "You can give power to a carving as long as you have the right incantations and as long as you make it the way you want it. Whether other people like it or not does not matter." 5 The carver imbues the sacred image with maneng through the use of magical leaves and by reciting specific timits (incantations) as he creates it. 6 Murik artists create works on a variety of scales. Larger human figures are primarily made for use as sacred images in the men's ceremonial house, whereas smaller examples, such as the present work, are used as amulets or set up in personal or household shrines. In the past, Murik men often possessed bags of amulets consisting of small anthropomorphic and zoomorphic charms, which served a variety of purposes, including hunting, fishing, and sexual magic, depending on the nature and form of the charm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a 19th-early 20th century male figure (Malita Kandimbwag or Murup) from the Murik Lakes of the lower Sepik region. Made by the Murik people from wood, it is 7.5 inches (19 centimeters) tall. This work may depict a male dancer, his face covered by a large mask and his knees flexed for dancing. Among the Murik, dancing is a sexually charged activity; the beauty of the dancers is often said to be so visually (and supernaturally) overwhelming that it results in seduction or jealous fights. Hence, it is conceivable that this work served as a love charm. The forehead is adorned with a motif known as mabranarogo (spider). The spider is considered the perfect designer because of the precision and intricacy of its web, and it symbolizes the artistic perfection that Murik master carvers seek to achieve in their own work. Htiltker describes human figures similar to the present one that, together with betel-nut mortars, were incorporated into a magic bundle on the nearby island of Kairiru. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

One of the most widespread practices in the western Pacific is the use of betel nut. As the nut is chewed, the individual periodically places it, together with a small amount of lime, in the mortar and crushes it with a small pestle to release the active ingredients and then places it back in the mouth. Born of necessity, betel-nut mortars also served as status symbols and were carried and used by male elders as marks of their secular and religious authority.' In some areas, the mortars became heirlooms, typically passed down by maternal uncles to their nephews.

On a 6-inch (15.2 centimeter), 19th-early 20th century, wood Betel-nut mortar in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection made by Murik people of the Murik Lakes, Kjellgren wrote: Often adorned, as here, with images representing spirits, ancestors, or other powerfu I supernatural beings, some betel-nut mortars also had magical properties. 3 The imagery of the mortars is diverse. Artists appear to have, or have had, considerable freedom in the choice and rendition of the subject matter of the central portion of the mortar, between the sturdy base and the shallow cup at the top, in which the betel nut is crushed. In many cases the cup is supported by single or multiple caryatid figures, which are often anthropomorphic in form. The bowl-like cup of this mortar, created by a Murik carver, is supported on the heads of two stylized female figures, which likely represent spirits.

Art of the Kambot People

The Kambot (Tin Dama) live along the banks of the Keram River, one of several major tributaries whose waters feed into the lower reaches of the Sepik River. As in other Sepik cultures, the primary focus of religious life and artistic expression in a Kam bot village was the men 's ceremonial house, whose towering gables, painted with the images of founding ancestors, loomed over the community.' Although Kambot artists devoted much of their time and energy to painting, they also produced compelling works of sculpture. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

A House-Post Figure produced in the 19th century in the Keram River area by the Kambot is made of wood, paint and fiber and is 8 feet (2.4 meters) tall. Carved from a single massive tree trunk, this monumental figure is probably the largest surviving work of Kambot sculpture. In its original state the figure was not an independent work; rather, it formed part of a massive post that helped to support the roof of the men 's house. At some later date, when the men 's house for which it was originally carved decayed and it became necessary to replace the edifice, the figure was cut from the post and preserved as a sacred image, tied to one of the house posts in the new structure and periodically repainted to refresh the vibrancy of its colors.

The images on Kambot house posts portray founding ancestors. This work may depict Mobul, one of the most important culture heroes of the Kambot, or his brother Goyen. The ancestor is shown in full ceremonial regalia, wearing large crescent-shaped neck ornaments of shell, fiber arm- and leg bands, and a row of circular shell rings or pigs' tusks around his waist. The head of the figure is particularly remarkable, for the form and configuration of the facial features can be interpreted as several distinct images. The overall form of the head may represent the head of a crocodile. It can also be interpreted as a stylized humanlike face whose greatly elongated eyes in turn form the arms of a second, smaller figure, whose head appears as a red ci rcu la r motif at the top and whose hands (the flaring nostrils of the larger face) grasp the long beaklike nose, which may refer through a complex series of metaphors to a sacred flute. Such flutes were secret and esoteric objects, the use or even the existence of which were known only to initiated men. Hence this image, which to the uninitiated simply depicted the face of the ancestor, almost certainly incorporated hidden imagery and deeper meanings known only to those to whom the figure's true significance had been revealed.

A 19th century house-post figure, made by the Kambot of wood, paint, fiber is 96 inches high, with a width of 23 inches and a depth of 18 inches (243.8 × 58.4 × 45.7 centimeters) This figure was not originally an independent sculpture but probably formed part of a housepost supporting the roof of a ceremonial house. The image represents either Mobul or Goyen, two mythical brothers who are associated with the creation of plants and animals. The brothers' spirits were believed to reside within the houseposts at certain times. This figure is probably the largest surviving example of Kambot wood sculpture. The head is a double image in which the eyes and nose of the central face also form the arms and flute of a second, smaller figure.

Kambot Paintings

The Kambot have combined sculpture and painting in complex, ambitious designs to decorate their ceremonial houses. The houses’ long, horizontal gables were filled with painted compositions of an ancestral hero with his wives and animals. One mid-20th century Kambot painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made of sago-palm petiole, bamboo and paint and is 5.2 feet inches (1.6 meters) long. Another mid-20th century painting made by the Kambot people of Sago palm petiole, bamboo, fiber and paint is 53.5 inches high, with a width of 29.4 inches and a depth of 3.6 inches (135.9 x 74.5 x 8.7 centimeters). Yet another is 63.75 inches high, with a width of 44 inches (161.9 x 111.8 centimeters)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: In former times, virtually all Kambot painting was devoted to the embellishment of men's ceremonial houses, whose massive exterior gables and more intimately scaled interiors were adorned with paintings depicting ancestors and other supernatural beings. Kambot men's-house gables were decorated primarily with a single, enormous painting depicting a prominent ancestor, which appeared above a row of smaller paintings portraying various subjects; the interiors were decorated with numerous smaller paintings. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

As in other Sepik cultures, the primary medium for Kambot painters was, and is, sago petioles, the barklike bases of the fronds of the sago palm. To prepare the petiole, the frond is trimmed off and the curved base flattened to produce a level painting surface. As in the present work, artists frequently stitch several petioles together with lengths of fiber to create a more extensive "canvas." Both the scale and the remarkable state of preservation of one of the works in the Metropolitan Museum of Art indicate that it likely adorned the interior rather than the facade of a men's house. The painting would have been attached to the rafters on the underside of the roof and might have been accompanied (as was sometimes the case) by delicate feather mosaics depicting similar images. The painting's energetically rendered figures, outlined in bright white pigment, would have exuded an otherworldly quality when illuminated by the flickering light of the fire. Such paintings primarily served as screens that separated the inner sanctum of the house from the remainder. Kambot paintings record and illustrate sacred history, depicting founding ancestors, culture heroes, spirits, and totemic animals from oral tradition. The present work shows a male ancestor in the center standing on a raised mound, flanked by two inverted female figures, who may represent his wives, one of whom stands on a similar mound.

The heads of all three figures are flanked by the heads of crested or wattled birds, which likely represent the ancestors' totemic species. Although the painting may be simply a portrait of these beings, some Kam bot artists also created narrative scenes representing specific events from the lives of the beings they portray. The unusual upraised hand gesture of the male ancestor here, as well as the inversion of the female figures, suggests that this image depicts an episode from Kambot oral tradition. A row of smaller paintings, similar in scale, was typically attached below the enormous ancestor image on the gable. Works that show no signs of fading or weathering indicate that they were almost certainly displayed inside the house.

House Post of the Bosngun People

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a house post from the lower Ramu River of the lower Sepik region, Produced in the early to mid 20th century from wood, fiber, shell and paint, it is 16 feet 2 inches (4.9 meters) tall. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Carved from a single timber, this imposing work, more than sixteen feet in height, once formed one of the central house posts in a men's ceremonial house in the lower Ramu River region.

Although house posts served as structural timbers that supported the roof, some examples, such as the present work, were also extensively sculpted, their surfaces richly embellished with figures and masks carved in such high relief that many of them st and nearly free of the post itself. Among the Bosman people of the lower Ramu village of Bosngun, the elaborate rites surrounding the erection of the house posts were one of the climactic events in the construction of the ceremonial house. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

When an old men's house had decayed and needed to be replaced, it was demolished. Provided they were still in good condition, the larger elements of the old house, such as house posts, were often preserved and reused, and the other remaining materials were burnt. The present work formed part of a ceremonial house constructed in the 1940s. Once the previous house had been torn down and the materials, including any reusable elements, for the new one had been assembled, men from the community and surrounding villages constructed the outer framework of the walls. After the framework was erected, the ceremonial erection of the house posts began.

The men and boys of the village first gathered to dig the holes in which the house posts would be set. Working with digging sticks and also with their bare hands, they dug the holes for the large central house posts first, followed by those for the smaller side posts. Once the holes were ready, the builders erected a tall fence around the building site to conceal it from the view of women and uninitiated children. Adorned in their finest dance regalia, with their bodies covered in red ocher and their faces colorfully painted in black, white, and red pigments, men from the village and surrounding communities gathered within the enclosure to celebrate witkurpag-a ceremony of singing, dancing, and feasting that accompanied the erection of the house posts. The ceremony was begun by the older men, who sang a song, accompanied by the rhythms of h and drums and slit 60 gongs, announcing that the posts would be planted the following day. After the song, the young men performed. As the sun rose the next morning, the men began to place the side posts in their holes, followed by the large central house posts. Although all the posts might be erected in a single day, days or months sometimes elapsed before the final house post was in place and the roof could be built and thatched.

Despite the prominence of the decorated post in the men's house, there is virtually no information about the significance of the figures and masklike elements that adorned them.Stylistically, lower Ramu sculpture is part of the broader tradition of the lower Sepik region, which includes the arts of the lower reaches and tributaries of the Sepik and Ramu rivers, together with adjacent regions of the coast, including the Murik Lakes, and nearby offshore islands. Both the style and the imagery of the present work, consisting of a series of superimposed figures interspersed with masklike images, are strikingly similar to those of the house posts of the Murik people to the west. 6 The figures on Murik house posts portray the major ancestors, spirits, and sacred masks associated with the men's house, and those of the lower Ramu likely depict similar subjects.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Museums Victoria, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, William A. Lessa (1987), Jay Dobbin (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025