Home | Category: Highland and Mainland Ethnic Groups / Arts, Culture, Sports

ART OF THE ABELAM PEOPLE

The Abelam live in the East Sepik Province of Papua New Guinea in an area that extends from the Sepik floodplains in the south to the foothills of the Prince Alexander Mountains (coastal range) in the north. Also known as Abulas, Ambelam, Ambelas and Ambulas they are divided into several subgroups; the most prominent is the Wosera, who are so named after the area they inhabit. This is the southernmost group of the Abelam. The other groups are named for geographic direction: northern, eastern, etc. The whole region is called Maprik, named after the Australian administrative post established in 1937 in the heart of Abelam territory.[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: Abelam art is rich, with the emphasis on painting. Paint is seen as a magical substance that gives life to a piece of wood (carving). Only then do the figures become powerful and active. Paint is a metaphor for a magical substance used in sorcery, which in this case is not life-giving but life-taking. Throughout Abelam territory different art styles can be recognized, although there are also many commonalities. Abelam artists are highly respected but only rarely do they serve as Political leaders. |~|

A Disk from a Top is a wood implement made by the Abelam people in the early to mid-20th century from coconut shell, Abelam people. Dating to the early to mid-20th century, it originates from the Prince Alexander Mountains in the Middle Sepik River and is one inch deep and 4.8 inches in diameters (2.5 x 12.3 centimeters). Another from the same time and place is .75 inches deep and 4.62 inches in diameter (1.9 x 11.7 centimeters).

RELATED ARTICLES:

SEPIK RIVER GROUPS: WHERE THEY LIVE, ART, SPIRIT HOUSES, CROCODILES ioa. factsanddetails.com

KWOMA (A SEPIK RIVER TRIBE): HISTORY, LIFE, ART ioa. factsanddetails.com

EAST (LOWER) SEPIK PEOPLE — BOIKEN, MURIK, SAWIYANO — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE LOWER (EAST) SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

ABELAM AND ARAPESH OF THE SEPIK RIVER: LIVES, HISTORY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

BIWAT (MUNDUGUMOR): LIFE, RELIGION, FAMILY AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART FROM THE MIDDLE SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA ioa. factsanddetails.com

IATMUL PEOPLE OF THE SEPIK RIVER: HISTORY, RELIGION, LIFE AND SOCIETY ioa. factsanddetails.com

ART OF THE IATMUL PEOPLE: MASKS, SLIT GONGS, BOWLS AND HOOKS ioa. factsanddetails.com

CHAMBRI: HISTORY, LIFE, SOCIETY, CROCODILE MEN AND MARGARET MEAD ioa. factsanddetails.com

WEST SEPIK HIGHLANDS PEOPLE — WAPI, TELEFOL, MIAN, GNAU, BIMIN — AND THEIR LIVES, HISTORY AND RELIGION ioa. factsanddetails.com

Abelam Ceremonial House Decorations

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: Most spectacular are the ceremonial houses (korambo ) with a large ceremonial ground (amei ) in front of it. Only major hamlets have a korambo, which may be up to 25 meters tall, with a painted facade. The korambo and amei are considered the village center but larger villages may have up to ten or fifteen such centers. The building material is timber and bamboo for the inner structure; sago palm fronds are used for the thatch. Lashing techniques are elaborate. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996 |~|]

The large painted facade of a korambo is visually dominated by big faces associated with ngwalndu spirits. Although ngwalndu are to some extent ancestral spirits, no genealogy is reported linking the living with these powerful beings who influence the life of men, plants, and animals. The soul of a man (that soul which is associated with clan membership) is thought to live after death with a ngwalndu. While ngwalndu seem to be the most important supematurals, there are nevertheless many others as well, both male and female. |~|

All art objects such as elaborately patterned plaits for the ceremonial house, carvings, and paintings, as well as decorated pots and bone daggers, are made by men for their ceremonial life. The Abelam artist, though esteemed as a gifted specialist, is a yam grower like every other adult male. Meshwork used as boar-tusk ornaments and worn by men during fights and ceremonies, featherwork, and rious body ornaments are produced by men who otherwise are not artists. Today the most important personal items of both men and women are net bags. (In former times both sexes were almost completely naked in everyday life.) The Wosera are among the most prolific makers of net bags. The production of net bags is known and performed by all women, though the knowledge of dyeing is limited to a few. Some women are renowned for their artistic skill. |~|

Abelam Initiations and Art

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The Abelam people practice perhaps the longest and most spectacular initiation cycle of any New Guinea people. Beginning in early childhood, each Abelam male must pass through a sequence of eight separate initiation rites, requiring some twenty to thirty years to complete, before he is considered a fully initiated man. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

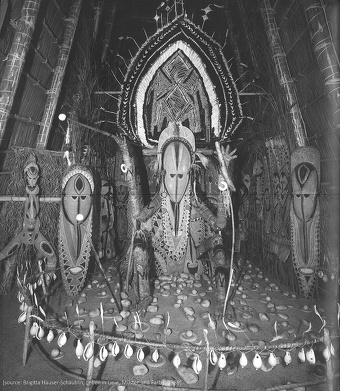

Held in the men 's ceremonial house (korombo), each successive ritual typically requires both a physical ordeal and the viewing of increasingly elaborate displays of sacred objects (maira) set up by the initiators in specially constructed chambers in the men 's house. These objects include brilliantly colored figures and paintings representing the powerful clan spirits known as nggwalndu as well as other beings. . As he begins each successive rite, the initiate is informed that he has previously been tricked-that the sacred displays he viewed before are not the "real" ones and that this time he will be shown the true sacred objects. This process continues until, in the final rites, the initiate is shown the largest, and most important, of all the sacred nggwalndu images.

When preparing each initiatory display, the initiators construct a chamber within the korombo whose walls and ceiling are Iined with dozens of paintings and wood figures depicting nggwalndu and other beings surrounding the large central nggwalndu figures. Working together, the artists creating the display consciously strive to achieve a magnificence that overwhelms the viewer with the complexity, scale, and brilliant colors of the sacred display.

A 1974 photograph shows a richly decorated Abelam initiation chamber inside the men's house (korom bo) in the village of Bongiora, The focus of the display is two massive nggwalndu figures, which are shown in a reclining position at the center. In its emphasis on visual magnificence, Abelam initiation differs from that of many other Sepik peoples. In most Sepik societies, male initiation involves extensive instruction of the initiates in clan oral traditions, the use and manufacture of ceremonial objects, and other religious esoterica. Abelam initiations, by contrast, are primarily experiential in nature. The religious experience comes not through formal religious instruction but from viewing the sacred displays whose nature and meaning are not explained to the initiates. It is only months or years later, as young boys assist their fathers in dismantling the displays or, as initiators themselves, participate in their construction, that the Abelam learn the specific identities of the nggwalndu involved and the details of building the displays in which they are revealed.

Nggwalndu Figures

Nggwalndu (“Father’s Father”) sculptures are ritual objects with supernatural power that watch over the yams and give strength to the initiates; They are considered to be inhabited by spirits and have a special function during the yam harvest and initiation rituals; Yams are a kind of giant tuber, regarded as spirits themselves, and are displayed in the cult house (ceremonial house, spirit house, men’s house, tambaran house)

The term Nggwalndu is used to describe powerful clan spirits as well as the art that depicts them. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Carved from a single massive tree trunk and ranging from eight to twelve feet (2.5-3.5 meters) in height, the largest nggwalndu images, such as the present example, are often displayed in a reclining position during the final initiation rite. Although nggwalndu images are often striking works of sculpture, to the Abelam their efficacy lies in the bright polychrome paints applied to their surfaces. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Among the Abelam, paint is considered a magical substance, from which the figures' power and beauty derive. The imagery of the figures unites the three central elements of Abelam male religious life: men, nggwalndu, and long yams. Although the nggwalndu have many different manifestations, in art they are represented in the same fashion: as vigorous men in full ceremonial dress. As one Abelam artist noted, "All those carved and painted objects are marvelous and holy. But the most marvelous and beautiful thing of all is a man with body decorations, adorned with flowers and feathers."

In Abelam art, men, figures, and sacred long yams (wapi) all wear distinctive triangular headdresses as well as elaborate face paint and body ornaments. The nggwa!ndu images typically consist of complete human figures, but occasionally, as here, they are more abstract compositions, with large heads and stylized bodies adorned with a diversity of smaller images.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Nggwalndu from Wingei village in the Prince Alexander Mountains. Made by the Abelam people in the 19th-early 20th century from wood and paint, it is 10 feet 11 inches tall, with a width of 14 inches and a depth of 12 inches (332.7 × 35.6 × 30.5 centimeters). This work retains much of its ceremonial paint; the eyes and headdress are accented with washing blue, an early form of clothes whitener introduced by European traders and used by many Melanesian artists to create a rich cobalt blue paint. Two large hooklike shapes loom over the spirit's head. These represent the heads and beaks of horn bills, large forest birds that are among the most important totemic species (djambu). The body of the figure is adorned with numerous smaller human images wearing the distinctive triangular wakan headdress and other ceremonial regalia, which are likely other manifestations of the nggwa!ndu. Impressive even now, when freshly painted and set amid the scores of brilliantly colored paintings and figures that lined the initiation chamber, their otherworldly features lit by the flickering fire, this monumental nggwa!ndu image must truly have inspired awe.

Nggwalndu Figure in a Cult House

This is an image of the male clan spirit Bira (nggwalndu), the most important among the ancestral spirits; The figure was displayed upright in the cult house (tambaran or korambo); His headdress is flanked by two hornbills, which are important totem animals among the Abelam people; The beaks of these birds are sometimes used as penis sheaths and are a symbol of masculinity; This sculpture and two other, larger figures in the MAS collection come from the village of Kalabu, Papua New Guinea; Such figures are also called Wapinyan figures; They belong to the Abelam culture of the Maprik area

The ancestor figures play an important role in men’s lives and in the rituals of the Men’s House; Therefore, they may not be seen by women and children; The artist is said to be Waulemoi, who is believed to have created the figures around 1978 on the occasion of a new Men’s House in Kalabu II/Kaumbul; According to the description by Alfons Borremans: On both sides of the head are the heads of hornbills (pal); The red triangle indicates the back-of-head decoration; Forehead ornament with feather decorations (síra-iwi) and a dog-tooth diadem (wasa-nimbi); Black cheek painting (kubmuingele): cockscomb painting around the chin

On both sides of the neck is the beak of the black cockatoo (mangge-nímbi), a Cymbium breast ornament, and trochus shell arm rings (duamal); Chest decoration (kovia); On the belly is an animal figure (gorono); the white, side, triangular decorations are space fillers; Accentuated penis; Stripes around the calves symbolize leg bands (manau); Between the legs, in traditional fashion, is a wild jungle fowl (saraguak) with its beak pointed toward the large penis to smell the semen; The stripes on the ankles show decorations made from half palm-leaf feathers (banjín); Additional ornamentation on the upper and lower legs has no symbolic meaning; At the bottom of the figure, also fully carved, are two bird heads

The artists (yalagi ndu, yigen ndu) are usually quiet and modest men who are not really among the clan’s leaders, but rather serve as a kind of priests, giving shape to the supernatural for the community; The sculpting of the figure is done by the artist alone; For the painting, the artist first draws the motifs on the figure using a white base color; his assistants then fill in the areas with red and yellow ocher; The sculpting and painting of these figures embody a recurring act of creation, in which each figure has its own name and represents a distinct primordial spirit, but their form and decoration always follow the same pattern

Tetepeku Female Figures

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The sacred displays and sculptures of the complex male initiation cycle of the Abelam people are often suffused with female symbolism and imagery. The men's ceremonial house (korombo) is seen as a female entity. The brightly painted panels that line the initiation chamber within are referred to as women 's string bags (wut) and the chamber itself is likened by some scholars to the womb. In the highest initiation rites, tetepeku, slender female images with long legs spread wide, are erected inside the korombo above the main entrance and also above the entrance to the interior passages and initiation chamber. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

As the initiates enter the house or initiation chamber, they stoop or crawl beneath the tetepeku, emerging from between its legs to enter the sacred space beyond, an act that likely symbolizes the rebirth of the novices as initiated men. To the uninitiated, not yet entitled to enter, the tetepeku is known as "she who blocks the road," and the space between the figure's legs is often closed off by her "string bag," made from the barklike petioles of sago palms, which serves as a door.Beyond the tetepeku, the full splendor of the initiation chamber, with its brilliantly colored paintings, carvings, and massive effigies of the clan spirits (nggwalndu), is revealed.

One Tetepeku Female Figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was produced by the Abelam people in the 19th or early 20th century in the Prince Alexander Mountains in the Middle Sepik region. Made of wood and paint, it is 42.5 inches (108 centimeters) tall. A similar one is 43.5 inches inches high, with a width of 23 inches and a depth of 7 inches (110.5 × 58.4 × 17.8 centimeters).

Although somewhat smaller in scale than other examples, this striking female figure is almost certainly a tetepeku. Carved fully in the round, it exhibits the bold, volumetric style characteristic of early Abelam sculpture; the features of later examples are considerably broader, flatter, and more schematically rendered. Like all Abelam wood images, when in use it would have been brightly painted with the rich red, yellow, black, and white pigments favored by Abelam artists. Often preserved and reused for decades, Abelam figures were carefully washed in running streams to remove both the physical and the magical traces of their earlier paint and then freshly painted each time they were installed in a new initiation display. Bearing evidence of many layers of paint, this venerable female figure likely witnessed the transformation of many generations of novices into initiated men.

Yua — Shell Rings Made from Giant Clams

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Fashioned from the hard, marblelike shell of the giant clam,shell rings (yua) were, and to some extent remain, the primary form of wealth among the Abelam people. Obtained through trade with neighboring groups, yua vary from small rings only a few inches in diameter to massive examples more than a foot (30.5 centimeters) across. Ceremonial valuables rather than ordinary currency, yua were displayed or exchanged as part of most major ceremonies and life-passage rites and were valued according to their size, age, whiteness, and regularity of form and texture. The largest and most prized examples bore individual names and histories and were often passed down as heirlooms-tangible symbols of the transmission of the power and authority of the ancestors from one generation to the next. So highly prized are the yua that an Abelam man, when wishing to emphasize the status of another man and his affection for him, will address him as "wuna yua" (my ring). Gifts or displays of yua accompany an individual throughout his or her life. At birth a ring is presented to the child's maternal uncle who, in the case of young boys, will later help guide him through the complex cycle of male initiations. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

At marriage the groom presents yua to the bride's parents, the number of rings he is able to give becoming a lifelong source of pride. At death, gifts of yua help ease the passage of the spirit into the next world. A dead person's spirit is believed initially to be weak, and a ring, presented to the deceased 's maternal relatives, ensures that the spirits of the mother's clan will "wash" the newly dead's spirit and watch over it until it becomes strong enough to join the company of its father's ancestors. In more sinister contexts yua can also be used as payment to specialists in malevolent magic. Beyond their roles in individual lives, shell rings play an integral role in village ceremonial life and serve as symbols of the strength and wealth of the community. At the dedication of a new men's house (korombo) vast numbers of rings are displayed on a fence erected in front of the facade. The rings are used, on occasion, to pay carvers for creating the initiation figures in the korombo.

At some initiation rites, large numbers of yua are laid on the 30 ground around the sacred nggwalndu carvings, which form the focus of the elaborate initiation display. At times some of the rings for the initiation display are lent by neighboring villages and are shown with a cassowarbone dagger placed through the center as a symbol of peace and cooperation between allies. Imbued with supernatural power by their presence in the ceremony the loaned rings are later taken home and washed in coconut milk, which is sprinkled on the local men's house, sacred carvings, and yams, transferring the power to the local community.

One shell ring (yua) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made in the Prince Alexander Mountains by the Abelam people in the 19th-early 20th century. Made of Tridacna shell, it is 10 inches (22.9 centimeters) in diameter. During the inauguration of a northern Abelam men's ceremonial house the festivities include displaying a huge number of valuable shell rings in front of the house facade, beneath the looming faces of the clan spirits (ngwalndu).

Abelam Masks (Baba Tagwa)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Abelam and neighboring peoples of the Prince Alexander Mountains in the Sepik region of northeast New Guinea create several types of basketry masks. They include the type, known in the Abelam language as baba tagwa, which is worn over the head like a helmet, as well as tje yam masks used to decorate the gigantic long yams grown and exchanged competitively by Abelam men. Among the Abelam, baba tagwa masks are associated with the male initiation cycle, in which they are worn by men clad in shaggy costumes made from strips of leaves. During certain ceremonies, these imposing masked figures serve as guards. Brandishing lengths of bamboo or other weapons, the baba tagwa drive off women, children, and uninitiated men, who are not permitted to witness the secret initiation rites.

One Baba Tagwa Mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made of fiber and paint by the Abelam people. Dating to the mid-20th century, it originates from the Prince Alexander Mountains in the Middle Sepik River region and is 16 inches high, with a width of 12 inches and a depth of 17 inches (40.6 × 30.5 × 43.2 centimeters). Another was made in the early to mid-20th century in the same place and is 18.12 inches high, with a width of 17.12 inches and a depth of 8.25 inches (46 x 43.5 x 21 centimeters)

Abelam Yam Masks

One of the major focuses of ceremonial life among the Abelam people of northeast New Guinea is the competitive growth and exchange of long yams. The Abelam cultivate two distinct categories of yams—a small variety used as ordinary food and long yams, massive tubers that can be as much as twelve feet long. A man’s social status is determined largely by his success in growing long yams. Each man has a permanent exchange partner to whom he ceremonially presents his largest yams following the annual harvest, later receiving those of his rival in return. Men who are consistently able to give their partners longer yams than they receive gain great prestige. Lavishly adorned for the presentation ceremony, the finest long yams are essentially transformed into human images, decorated in the manner of men in full ceremonial regalia. The “heads” of the enormous tubers are adorned with specially made yam masks such as this one, which are made exclusively for yams and are never worn by humans. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

One Yam Mask at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made of fiber and paint by the Abelam people. Dating to the early to mid-20th century, it originates from the Prince Alexander Mountains in the Middle Sepik River region and is 28 inches inches high, with a width of 12.5 inches and a depth of 10.25 inches (71.1 × 31.8 × 26 centimeters). Another made in the same time and place 25 inches (63.5 centimeters) tall.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Yyam masks typically consist of highly stylized human faces crowned by the distinctive triangular ceremonial headdresses worn by Abelam men. Below the mask the "bodies" of the yams are richly embellished with men's ceremonial ornaments, such as shell rings and feather plumes, as well as more ephemeral decorations of leaves, flowers, and brightly colored fruits. In some cases the yams are further embellished with the body-paint patterns worn by dancers at initiation celebrations.The shared imagery of the decorated long yams, human performers, and wood images reflects the spiritual unity among yams, men, and nggwalndu in Abelam cosmology. Once displayed in all their finery, the long yams are presented to the exchange partner. The masks and ornaments are removed, and the yams are eaten or placed in the village storehouses.

Abelam Exchange of Long Yams

Eric Kjellgren wrote: In addition to the complex cycle of male initiations, the second major theme of Abelam religious life is the growth and ceremonial exchange of long yams.' The Abelam recognize and cultivate two distinct categories of yams, a small variet used as ordinary food and long yams-massive tubers that commonl attain lengths of six to nine feet (1.8-2.7 meters) and, in exceptional cases, can be up to twelve feet (3.7 meters) long. An Abelam man 's social status is determined not only b his abilities as an orator and, formerly, a warrior; it is also, quite literal!, measured by his success in growing long yams. The cultivation of long yams is a sacred activity, surrounded by magic and ritual restridion. It is also highl competitive. Each man has a permanent exchange partner (chambera), to whom he presents his longest and largest yams following the annual harvest, receiving those of his partner in return. As the massive yams are presented, they are measured and their dimensions carefully noted. Men who are able to present their chambera with longer yams than they receive gain prestige and renown, while the reputations of those who repeatedly fail to do so are correspondingly diminished. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In contrast to male initiation, the exchange of long yams is a highly public affair in which each man brings his best tubers to be displayed on the village dancing ground (amei) in front of the men's ceremonial house. Lavishly decorated, the largest examples are suspended in a reclining position from long poles, and crowds of people from the village and neighboring communities gather to witness the spectacle and inspect the achievements of the yam growers. The cultivation of long yams is under the patronage of wapinyan, beings who are manifestations of the powerful clan spirits known as nggwalndu, whose images lie at the center of the male-initiation cycle.

The enormous yams are regarded not as tubers but as living supernatural beings with humanlike qualities, able to hear and smell but lacking the powers of movement and speech, and the largest examples are named after the nggwalndu of the owner's clan. During the rites the yams are essentially transformed into ornate anthropomorphic images, which, like wood nggwalndu figures, are decorated in the manner of men in full ceremonial regalia.' The "heads " of the enormous tubers are adorned with specially made yam masks of basketry or wood, which are created exclusively for this purpose and never worn by humans.

A photograph from the late 1950s or early 1960s shows a decorated long yam on display during an Abelam yam-exchange ceremony. Suspended from a supporting pole, the massive tuber, only a portion of which is visible, is adorned with a basketry yam mask and ornaments made from shell, feathers, and other materials.

Abelam Dagger

A dagger at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was made in Sunuhu village Toricelli Mountains in the Sepik region, by Kwanga people, who are related to the Abelam. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of Cassowary bone and pigments and 14.5 inches (37.1 centimeters) long According to the museum: Warriors in the Sepik region formerly employed a variety of weapons, most of which, such as spears and arrows, were intended to strike the enemy from some distance.

However, men also carried daggers for use in close combat. With blunt edges but finely sharpened tips, daggers were exclusively stabbing weapons and were often used to deliver the coup de grace to an enemy felled by other weapons; at times they were utilized in more st ea I thy acts of assassi nation.' Beyond their practical function, daggers were supernaturally powerful objects that frequently played important roles in male initiation and other rituals. Highly ornate examples, such as the present work, which has a relatively blunt tip, may have been created solely as ceremonial objects or personal ornaments.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Like this example, the majority of daggers in the Sepik region were fashioned from the leg bones of cassowaries, large ostrich like birds that roam the forests of New Guinea. In rare instances, they were made from the femurs of ancestors or enemies. Hard and durable, cassowary bone was an ideal material for daggers, but it was likely prized for its supernatural properties as well. The cassowary plays a central role in the origin traditions of a number of Sepik peoples. In some instances, a primordial cassowarywoman is said to have created both the world and the first human beings. 5 Whether a primeval ancestor or a living bird, all cassowaries are believed to be female, and the fleshy wattles that hang from their neck are identified as breasts. 6 However, the powerful, dangerous birds simultaneously embody aggressiveness, the ideal quality sought by a male warrior.-Through the use of its bones, artists and warriors likely sought to impart to themselves aspects of both the ancestral power and the ferocity of the cassowary.

The present dagger was carved by an artist from Sunuhu village, which lies at the eastern edge of the lands of the Kwanga people. Among the Kwanga, bone daggers appear to have been confined almost exclusively to the eastern region, and their imagery reflects strong artistic influences from the neighboring Abelam, Arapesh, and mountain Boiken peoples. The upper portion of the grip is adorned with a highly stylized human figure, from whose head two scroll-like motifs emerge to form a triangular headdress, closel y similar to those worn by nggwalndu (clan spirits) in Abelam art. The pointed-oval shape of the body also resembles those of Abelam and llahita Arapesh images. Instead of legs, the lower end of the body has a second head, clad in a similar headdress.

The significance of this double-headed image is unknown, but it may portray, in highly abstract form, the union of powerful male and female beings. A row of three smaller figures, reminiscent of those that once appeared on the lintel of the men's ceremonial house in Sunuhu, appears below. The precise identity and significance of the three figures are uncertain, but, like the larger figure on the grip, they probably represent potent supernatural beings.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, William A. Lessa (1987), Jay Dobbin (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025